“Art wants to make itself the likeness of an in-itself, of what is free of domination and disfigurement. Art is the spirit that negates itself by virtue of the constitution of its own proper realm” Theodor W. Adorno “Aesthetic Theory”.

The exceptional Syrian situation that has been unfolding since spring 2011 prompted Syrians, including artists, to pose radical questions about the meaning of identity, belonging and artistic work. These questions intertwined with the artist’s personal journey and with the connection of their creative work to public affairs; whether this connection is weak or strong. These questions were raised amid the harshness of a rapidly changing present and the destruction of places and memory that ruptured society.

The Syria of one leader forever is gone. Eight years on, several publications and research papers have tried to study this change and analyze it. Some of these publications carried an aspect of documentation, like the Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution, and The Story of a Place, the Story of a People, the Beginnings of the Syrian Revolution 2011-2015 book. Other publications were artistic and literary works like Syria Speaks anthology book, and personal testimonies like the series published by Citizen’s Home and others.

Among the arts that flourished in the past eight years, plastic arts were the most prolific, varied and widely spread, because of the strong impact of visuals and the ease of their distribution. Many artists moved outside Syria, and they were able to continue working freely and safely.

This paper, which is part of wider and more detailed research work, tackles the relationship between plastic arts and the society in Syria before spring 2011, and the impact of the Syrian revolution on plastic art trends. The paper will also chronicle the transformation of some Syrian artists, based dialogues and recorded interviews that I conducted in summer and fall 2018.

Art and society before spring 2011

“The dictatorial surveillance state, on the other hand, is omnipresent. So it is hardly surprising that the visual arts in general appear rather innocuous, lacking in challenge. Take for example the works of the talented 26-year-old Abdelkarim Majdal al-Beik, who visualises the theme of time by depicting dilapidated old house walls. One might be tempted to ask why the artist ignores the question of what is going on behind those walls.” This is a quote from an article written by Mona Sarkis and published on Qantara website in 2010, and it summarizes the situation of art in Syria before 2011.

The expression “innocuous” insinuates implicit obedience and the dominance of a regime that hid the reality of the Syrian society. However, silent references of hidden realities in Syria were part of everyday conversations in public life in general, and were not just restricted to the level of art. Despite this dominance, artistic creation did not stop. On the contrary, demand for Syrian art, like the work of Fateh al-Moudarres, Mahmoud Hamad and Louay Kayali increased after 2000, but those who were enthusiasts of this art were outside Syria—the internally suffocating and blockaded country. This contradictory nature, between isolation and openness, which Syrians coped with, blew up in everyone’s faces shortly after.

Syria has changed drastically over the past eight years. A few years earlier (2006-2010), a surprising transformation appeared in the plastic arts’ scene, when new galleries were opened (Ayyam Gallery 2006 and Tajalliyat Art Gallery 2008), and cultural cafés in Damascus constituted a meeting spot for writers, artists and journalists from different Syrian areas.

After the year 2000, when Bashar al-Assad acceded to the rule, a new wealthy class emerged in Damascus and Aleppo. Artist Nasser Hussein, who studied art in Damascus and Dusseldorf and now lives in Berlin, believes this political transformation and supposed economic openness were coupled with two things: an increase in the price of artworks and their marketing techniques, and the decrease or absence of themes that once distinguished Syrian art in general.

Perhaps Hussein’s remark signifies the lack or decline of the local character of Syrian artwork and the trend to abide by the galleries’ preferences. These galleries are focused on selling abroad and opt for what sells over what helps artists develop their own choices. If this conclusion is accurate in principle, galleries are then an artistic authority exercising its pressure, just like the oppressive political authority. As a result, artists ended up being stifled with a dual authority.

Some considered this cultural transformation as a sign of artistic boom, despite critical discussions about this trend taking place at the time. An article by Rana Zeid published in Al-Hayat newspaper read, “The French Cultural Center in Damascus presented a lecture end of 2010, that had a resounding name ‘Contemporary Arab Art in the Age of Globalization: Risks of a Success Story.’ The center advertised for the lecture through road banners showing Sabhan Adam’s work [Syrian Plastic artist]. Researcher at the Institut Français du Proche-Orient Yves Quijano did not say anything new in his lecture, but he randomly examined the reality of plastic art, focusing specifically on the argument between Ayyam Gallery, and artists Youssef Abdelke and Safwan Dahoul on the pages of As-Safir newspaper. His conclusion was that ‘some artists caved in to the temptations of financial profit that would result from a better international recognition. But, others questioned the status that a new wave of artists now occupies in plastic arts.’ Quijano easily judged Syrian art as lacking identity and concluded that Syrian art follows international trends.”

Contrary to the exchange of accusations and the critical controversy like in the article (Answering the Critique: The Science of Mercenary Beauty), there was another optimistic and inquisitive vision.

Curator Maymanah Farhat presented Syria’s Apex Generation (2014) by saying, “During the early 2000s Syria’s art scene experienced significant growth as nationwide economic reform policies were implemented. New galleries opened; numerous events were launched in partnership with organisations abroad; and the rising profiles of established art spaces like Le Pont Gallery in Aleppo continued to attract international artists and curators. These factors, combined with a push from the rise of an art market in the Gulf, changed how art was created, distributed, and received.” Farhat shed light on the experience of Abdul Karim Majdal al-Beik, Nihad al-Turk, Othman Moussa, Mohannad Orabi and Kais Salman whose artistic experience constitutes a window to examine a wider cultural history.

In fact, this new space for art, which appears active, contradicts the actual lives of artists.

Iman Hasbani, who moved to Berlin in 2015 said, “My relationship with the public space is weak and fragile. For that reason, I felt I did not belong, and the feeling was exhausting. I lived in Damascus for around 20 years. We shared common interests in the small community within the Faculty of Arts, but we knew nothing about life on the outside. Damascus was an unknown to us, except for cinemas or theaters, which are closed spaces with an atmosphere similar to that of the Faculty of Arts.”

The situation was not any better for the field of journalism and art critique.

Adel Daoud, who was born in Al-Hasakah in the northeast of Syria and currently lives in Vienna, said “Generally, I did not notice a serious and professional attitude in arts’ journalism in Syria. I think journalistic critique was more like flattery that lacked credibility.”

Ghailan al-Safadi who hails from As-Suwayda in south Syria and now lives in Beirut added, “Unfortunately when I was a student, we did not have specialized journalists who interpreted art and its aesthetic aspects.”

Notably, most Syrian artists are not from Damascus, which is home to the Faculty of Arts that was established in 1962. They lived in Damascus for a long time, yet the city never appeared in their work. The city was absent, while art was present. The same applies to the flourishing television productions, which opted for consumerist comedies or Ottoman or French history of Syria. According to this approach, Damascus was presented as an old city, and its contemporary and daily affairs had no noticeable presence. Eliminating the present moment and daily life from public debates and from art mainly aimed at obscuring the apparent reality seen before one’s eyes, in favor of highlighting an imaginary past that is in line with the regime’s propagated image of Syria. This is how art served the regime, unintentionally. A full, closed circle controls the propagation of certain ideas or the promotion of artistic and literary work, which should not tackle taboos or political material and must not contradict the views of the ruling regime.

The aesthetic value of art had no connection to present life and contemporary living, and this (phenomenon) could be traced back to educational curricula, where art is stiff task and reflects mysterious eternal waiting. We saw these features in the sculptures of Mohammad Omran (who moved to Paris in 2010). Another reason behind this phenomenon is the censorship role of the ruling regime, as it appeared in the work of Walaa Dakak (who now lives in Paris).

The role of the arts’ teacher at the Faculty of Arts was generally negative, theoretical and had a rigid conceptual character in a field of study in which everything was becoming tangible and sensual, according to Hasbani and Nagham Hodeifa (both interviewed in person). Artistic choices were also based on coincidences, according to Yasser Safi, (born in Qameshli and living now in Berlin).

Hodeifa who now lives in Paris, and who finished her Doctorate thesis in 2015 about Syrian-German artist Marwan Kassab Bachi, said she experienced the impact of art through the eyes of a child more than learning about it from her teachers at the Faculty of Arts. “I hated everything written about art in Syria, and I wished nothing of the sort were written. Arts’ journalism and critique were repugnant,” she said.

The impact of the conflict

“The revolution shook the concept of art’s purpose to its foundations.” Syrian poet and journalist Elie Abdo reached this conclusion in 2014. Art began to question the roots and basis of things, and the definition of the functions of poems, paintings, songs and culture was changing and becoming separate from the regime popular propaganda and the notion of “committed art” in Syria.

Popular art that accompanied the revolution, in songs and performances, identified with the direct and instinctive, and the instantaneous and spontaneous. This art came from marginalized groups outside the familiar cultural field. With that, traditional and local art seemed richer, deeper and more modern than the stagnant “committed art” that had no real connection to the real lives of the Syrian people.

Syrian artists soon found themselves up against death daily. Since spring 2011, the relationship has changed, with the emergence of personal questions about the private past and public life of the artist, place and memory, art, truth and freedom. Between 2012 and 2015, most Syrian artists had left Syria.

Place and memory

Sculptor Nour Asalia moved from Salamiyah town in Hama to study in Damascus, and she currently lives in Paris where she is writing her Doctorate thesis about fragility in sculpting. She believes her connection to people is more important than that to places; the place is the person. Asaliya does not feel nostalgic to Damascus or to Salamiyah— the city where she spent her childhood.

“Artists had to have an embellished image and had to be present in circles different from their real environment, not necessarily because of class differences but because of intellectual and knowledge-based disparities that estranged them from the circles of painting collectors and gallery owners. But, this seems to be the case in Syrian society in general, where we show what we are not in an attempt to hide what we believe tarnishes our image or the image we would like to convey,” she explained.

It was not possible to give such testimonies in the past. The space for critique was narrow and mundane. It was closer to reporting news rather than presenting an analysis. Therefore, artwork was received objectively or neutrally, even if it was not objective essentially. This objectivity creates cold reception of art and its impact and overlooks the personal story of the artist. The art is presented as abstract and devoid of any clear connection to the place where the artist lives.

On the other hand, directly linking art to the revolution surpasses change that occurred in the art piece itself, by turning it into a political message that transcends differences and disparities. This process happens at the expense of the artist as an individual and of art as an unconditioned choice. Perhaps this shallow political correlation tarnishes the artistic/social connection instead of examining it. The revolution is not only a change in people’s movement and expression, but it also alters the person/artist from the inside. The artist is not a mechanical creature merely creating work as a reaction to a revolution, nor the revolution should be transformed into the benchmark against which all artists are assessed.

The regime, art and functionality

The Syrian regime essentially aims at determining the functions of anyone who is not affiliated with it and seeks to undermine these people by limiting them to a pattern that cannot be broken or overcome. Accordingly, artistic space is defined by and limited to “beauty” and “beautiful objects”, which are two abstract notions without any links to a specific time and place. Just as Syria had always been a state whose function is related to more important affairs that exceed its borders and the choices of its people, as defined by the regime ideology, art also had its official functions.

Naturally, art and artistic work are not part of any regime. Therefore, Syrian artists are a targeted category, despite contrary allegations. This targeting is complete and expresses itself through determining the general trend of art, and defining it as a function rather than a personal choice and as a way to indoctrinate and convey messages rather than experiment and be spontaneous. This inclination undoubtedly erases the individuality of the artist whose most important form of self-expression is his art.

However, and after 2011, one must not ignore that the revolution also allowed art to be employed for the sake of one purpose, especially as reflected in the media. This gives the impression of reverse similarity: regime/art/function as opposed to revolution/art/function. It is a vicious circle in terms of defining and employing art for a political purpose despite the huge difference between the two cases.

Oral memory, lack of documentation

Syria is a country that has no archive. It was forbidden to discuss its daily affairs and its contemporary history, or then to study and document it. Syrian society lives and dies trapped inside a discontinuous and interrupted collective memory, passed down from generation to generation and from one region to another orally and many details become obscure or lost. . Perceptions that are closer to inanimate ideals became widespread, while oblivion engulfed entire decades we almost know nothing about. Perhaps this is one of the reasons behind the weak connection to the history of places and the stories of their local residents many artists described. And this happened after living turned into a mechanical act, even for those outside the fixed frames of bureaucracy and routine.

Political reality, artistic expression

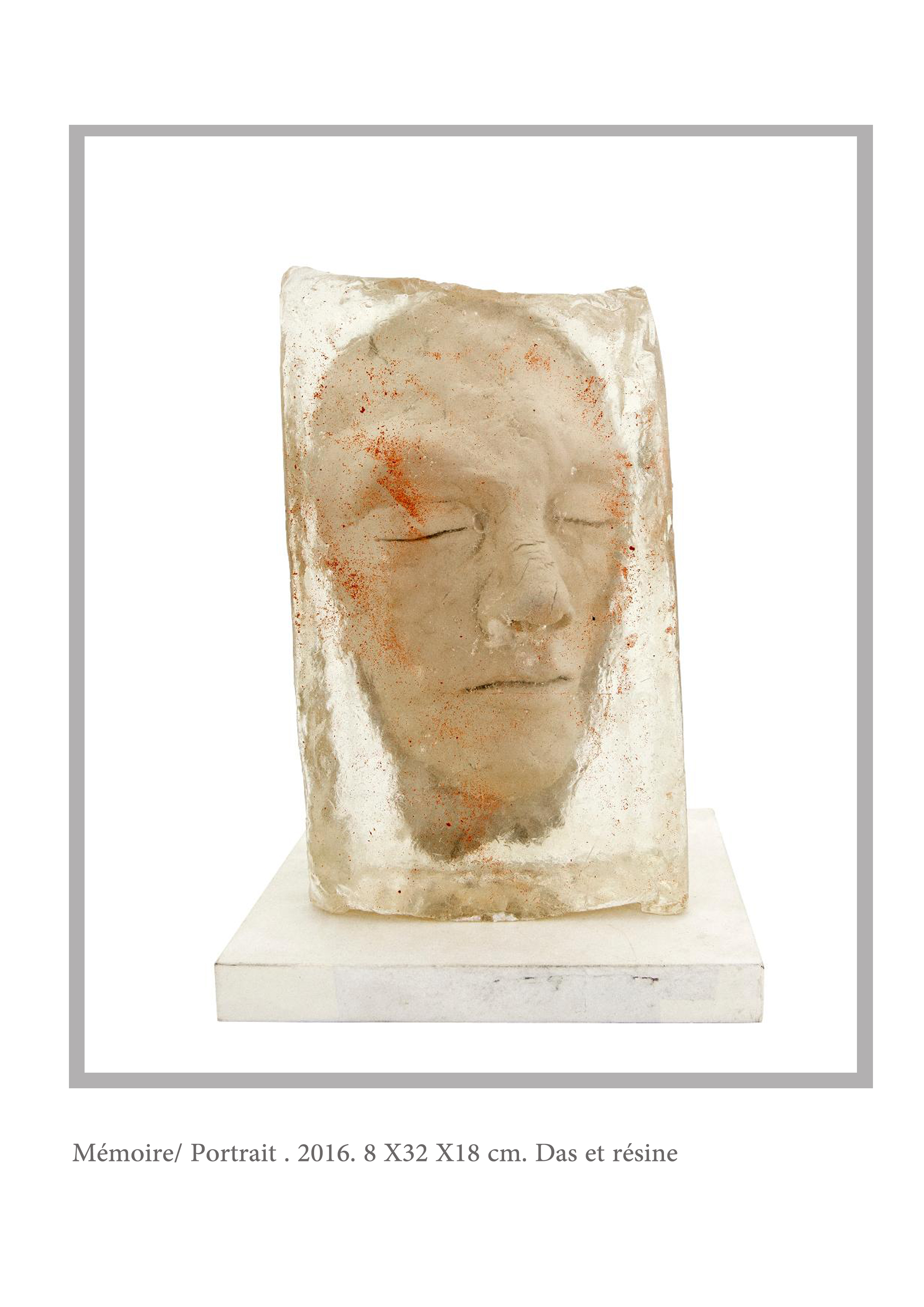

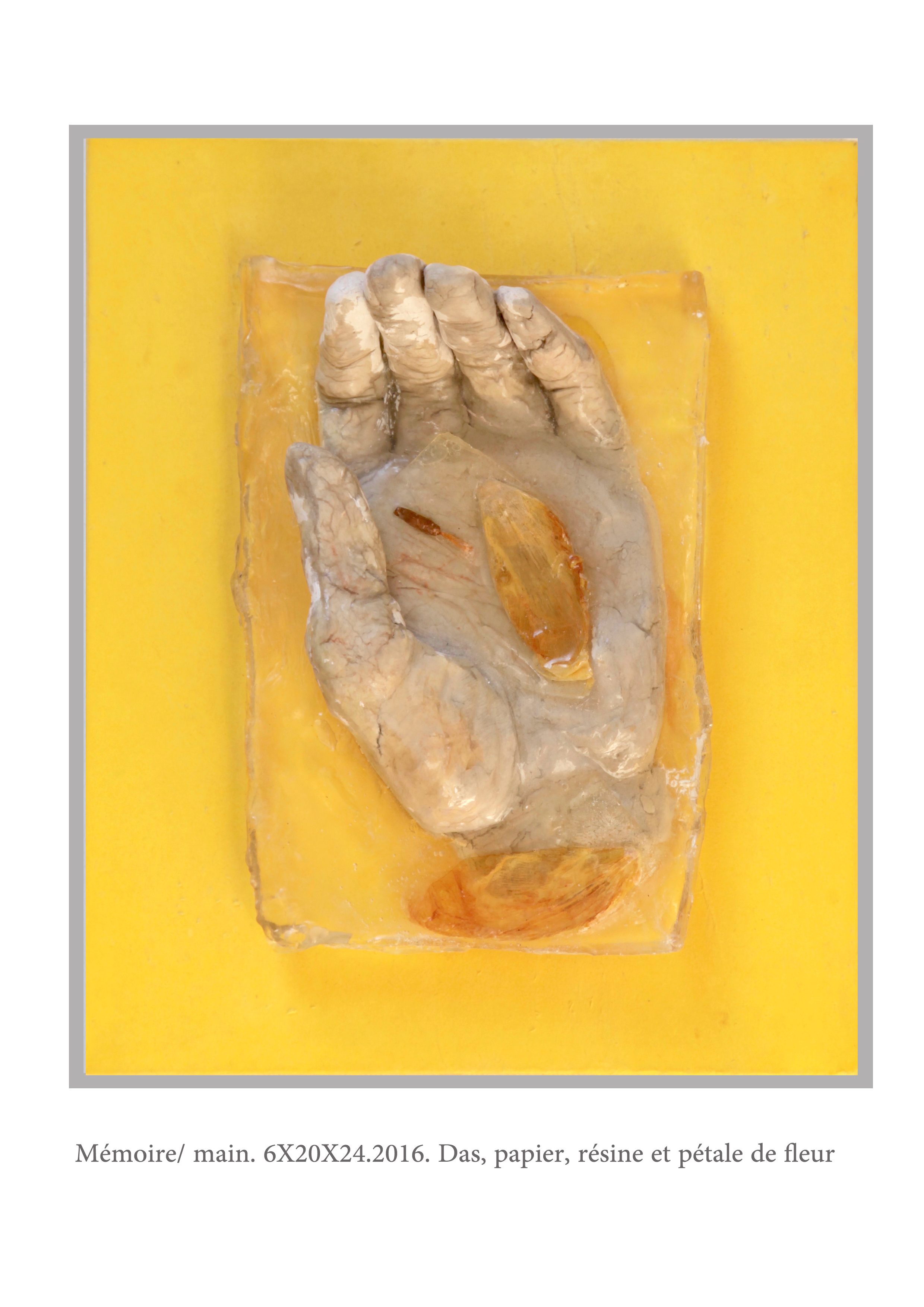

Art does not define politics, but it lives amid political truths. The importance of art stems from an indirect core that goes beyond the moment when the artwork is completed. It provokes memories, but also the piece seems to take a step forward through reprocessing the present. The distance in art gives its independence. Artistic work in that sense is composed of two separate, yet intertwined, moments. The first lies in the artist’s past as recalled by memory, and the second is how the memory manifests itself through art, as we see in Nour Asalia’s Sculpture Collection (Memory) which focuses on a pivotal moment— the moment that precedes death.

As such, artistic work expands time and does not remain hostage to a specific suffocating political crisis, even if that crisis might have led to its emergence. Artistic work is not the result of political changes. It is neither instantaneous nor accompanies events and society in their transformation and movement. A painting does not need social concepts and realities to become what the artist dreamt of achieving. Perhaps the most dangerous idea is turning artistic work into a document, as art does not replace history. Art is not history, but it can indicate to this history from outside of it. We can thus find a sociopolitical dimension in art, since artistic work can serve as yet another way to read society.

Center and periphery/dual schism

Most Syrian artists do not hail from Damascus. More often than not, the capital which the artists lived in was not a theme in their work, and they did not study modern Syrian art.

According to Omran, “Friendships were the upside. Lectures, in general, were not good. The material and books covered the epoch only until the 1960s, because the teachers received their education in that period. The thing that meant we were far from contemporary work.” Consequently, artists developed a distictive work pattern that relied on their memories and previous homes before moving to Damascus to receive their education and live, or relied on places they discovered within themselves through a personal quest. That place was neither the center nor the periphery. In any case, it was apparent how weak the connection they had with the actual place of their current residence.

Academic relations were generally not so good. In some instances, they were negative, as was the case for Hasbani who moved to Berlin four years ago and Hodeifa who lives and studies in Paris now. Critical journalism was extremely bad, minus a few exceptions, like Abdul Aziz Aloun whom Asalia referenced and Asaad Arabi, according to Yasser Safi.

Sulafa Hijazi who grew up in Damascus and studied theater there currently lives in Berlin. She noted the presence of a cultural sect that lived outside Damascus, despite coming from different Syrian areas and residing in Damascus. This sect created a modus vivendi that had no connection to daily life in Damascus. It was not linked to cities and villages which these artists, writers and journalists hailed from. Art and the cultural milieu played a strange and familiar role at once, either consciously or unconsciously, and whether by being complacent or simply due to lack of other possibilities. They elevated the artistic and cultural field which cut its connection to the place and society, gave art a preconceived value— a value that is irrespective of time— and narrowed the sociocultural act to a mechanical, functional one.

The event and its interpretation

Perhaps it is better to look at Syrian art and its connection to an exceptional event, as much as it is important to view it as independent of the revolution and as an absolute principle. With that, art is defined as a circumstantial instinctive knowledge and personal experience that does not stem from one foundation. Still, art is neither neutral nor is it a mere physical representation.

Artistic work involves interpretation and critique of society without mirroring it. Art is inspired by society, but it eventually becomes a separate entity from its source of inspiration.

However, and that is an important point, any work of art is an event in itself. It is not a comment on an event or a transference of it, despite the influence of the event on the artwork. Art is an event in the social sense and has its own space and spirit. It chisels its spot in a particular place. Collective memory is not limited to public events, and we may be more influenced by imagination more than reality.

German - Syrian Art: A Concise Comparison

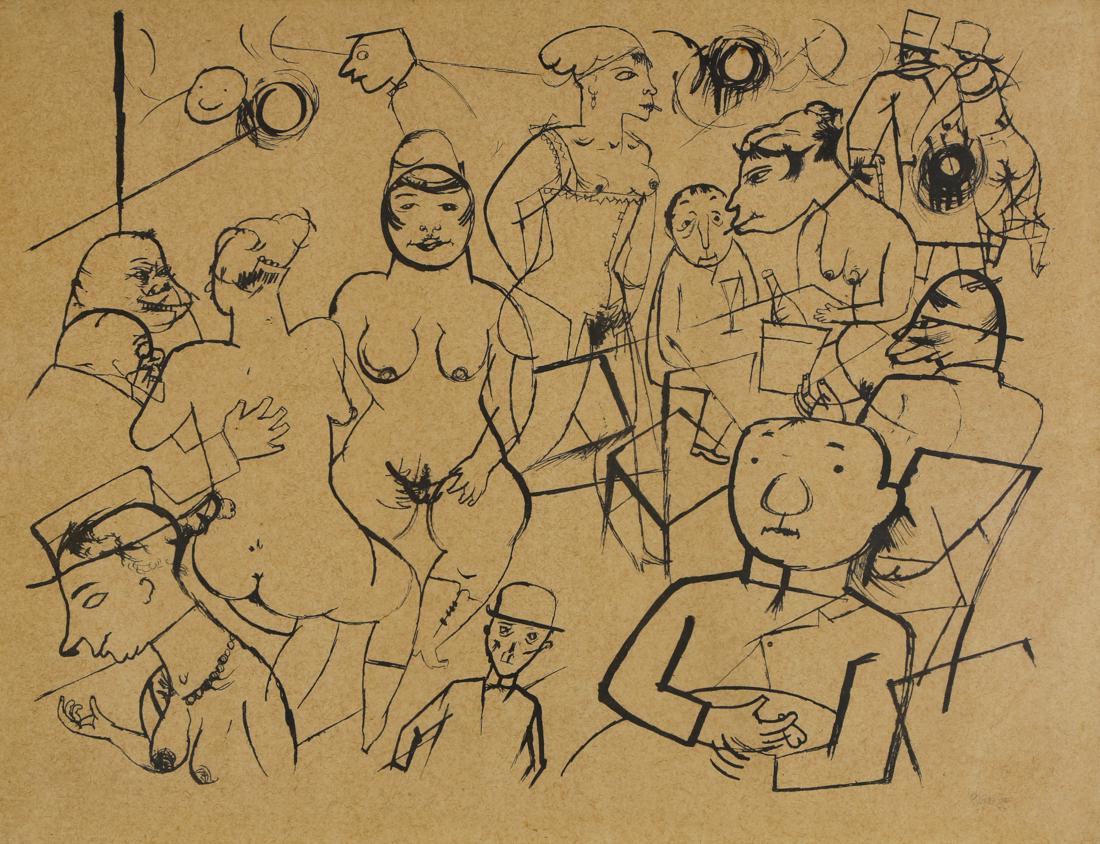

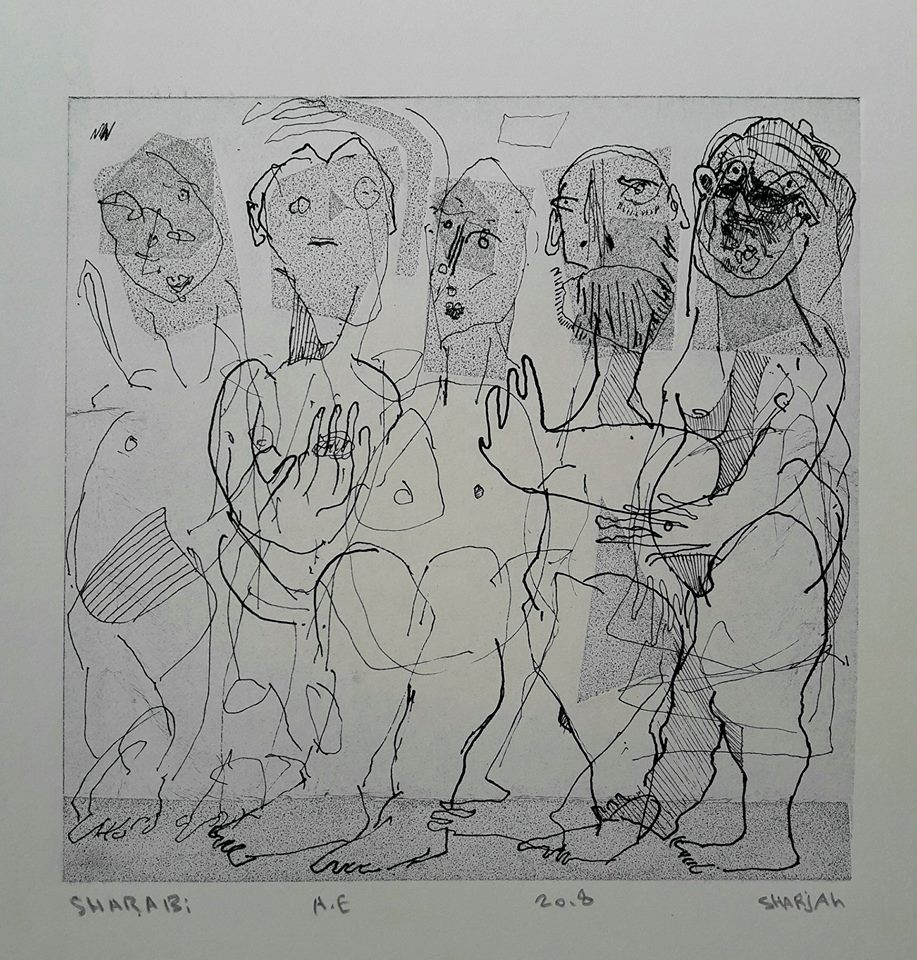

German artists tackled war and violence. They depicted the social gap, especially after World War I, and ridiculed the ruling military class. This was heavily echoed in the paintings and drawings of George Grosz (1893-1959), Max Beckmann (1884-1950) and Otto Dix (1891-1969). Grosz's Ecco Homo in 1923 and Hintergrund in 1928 showed graphic features with fine sculpture-like lines. The drawings portrayed military faces and soldiers with distorted and sharp figures, war victims and disabled confronted with the wealthy and indifferent class.

German art excelled in portraying these contradictions. These artworks are now part of the cultural and political history of Germany.

The sketches of Abdul Karim Majdal Al-Beik focus, relatively, on the same subject. His artworks depict a frail and austere shape, one that stands as a mockery of the fake and pretentious machismo. His works lacked social features, showing only soldiers and officers.

Yasir Safi's paintings convey a sense of irrationality, infantile fantasy, rawness and semi-primal nature. Physical rupture and social dispersion are more pronounced in the style of Tammam Azzam, at his lastet exhibition at Berlin’s Gallery Kornfeld.

Art Society / Documentation and neutrality

Artwork is not an automatic outcome of political changes. But distancing art from politics and society could be an illusion or some kind of additional repression. Perhaps the most dangerous misconception is defining art as a documentation tool. Art could never be a substitute for history.

The most important thing, I believe, is that an artwork is an event in itself. The value of the artistic event is that it can serve as a historical reference.

Art may be fragile, even if it seems strong in its visual appearance. Art has its own distinct existence and entity. Moreover, art provides a gateway into the history of a society where destruction prevailed over arts. This creates a counter-tendency among artists, who find in their artwork a means to overcome this destruction and immunize collective memory against violence and forgetfulness.

Syrian artists are not a single bloc, and they have not developed a special intellectual trend. We may see this as a good thing that promotes diversity and uniqueness. But perhaps, this may also suggest a kind of rupture within the artistic community itself.

This rupture, or the state of intermittent cooperation, or instantaneous competition or total estrangement are rarely subjects of observation within the artistic community. Added to those problems are the obstacles in managing the relationship with galleries. There have been some discussion about these issues and rumors, but they remain unverified and void of critical review.

During interviews, many Syrian artists usually talk about their private life. They prefer to talk about themselves as an independent individual. Meanwhile, some refer to tensions and lack of intellectual harmony, and complain about an exaggerated appreciation of the value of certain artworks, saying that reason behind that is not their excellence, but because of media praise. They refuse to give specific names in their criticism.

In Conclusion

There is a huge gap between society and art in Syria, and this gap resulted from police censorship, academic orientation and the definition of art itself as a concept and practice. According to sculptor Alaa Sharabi who moved from Damascus to the UAE, this applies to the quality of journalistic coverage. “This [coverage] was ornamental, praising the artist's experience in poetic terms.”

This, combined with the emblematic and exaggerated nature of critical writing, deprived society of art critique and distanced art from society. Labeling living and artistic domains and disassociating them is a main feature and phenomenon of the Syrian situation.

However, the art broke free from the static and rigid rhetoric after 2011. Art became more discussed and became a subject of political controversy. Artists found new meanings for their works that gained tangible relationship with their country, despite the superficial and sometimes chaotic media demand.

Yasser Safi, Iman Hasbani, Abdul Karim Majdal Al-Beik and Nagham Hodeifa believe this media demand confines them within the narrow definition of “refugee.” This would obliterate the artists’ lives and personal experiences, and overlooks their importance as individuals rather than samples of a savagely war-torn country.

Faced with fears of oblivion or frustration, art stands as a powerful force. Art transfers memory and transforms it from a mysterious public realm into a deeply rooted personal experience that restores the artist's connection to society as an individual and his relation with himself, before artistically lablelling him as a trending artist above being a refugee.