This article was originally published on openDemocracy. You can read the original article here.

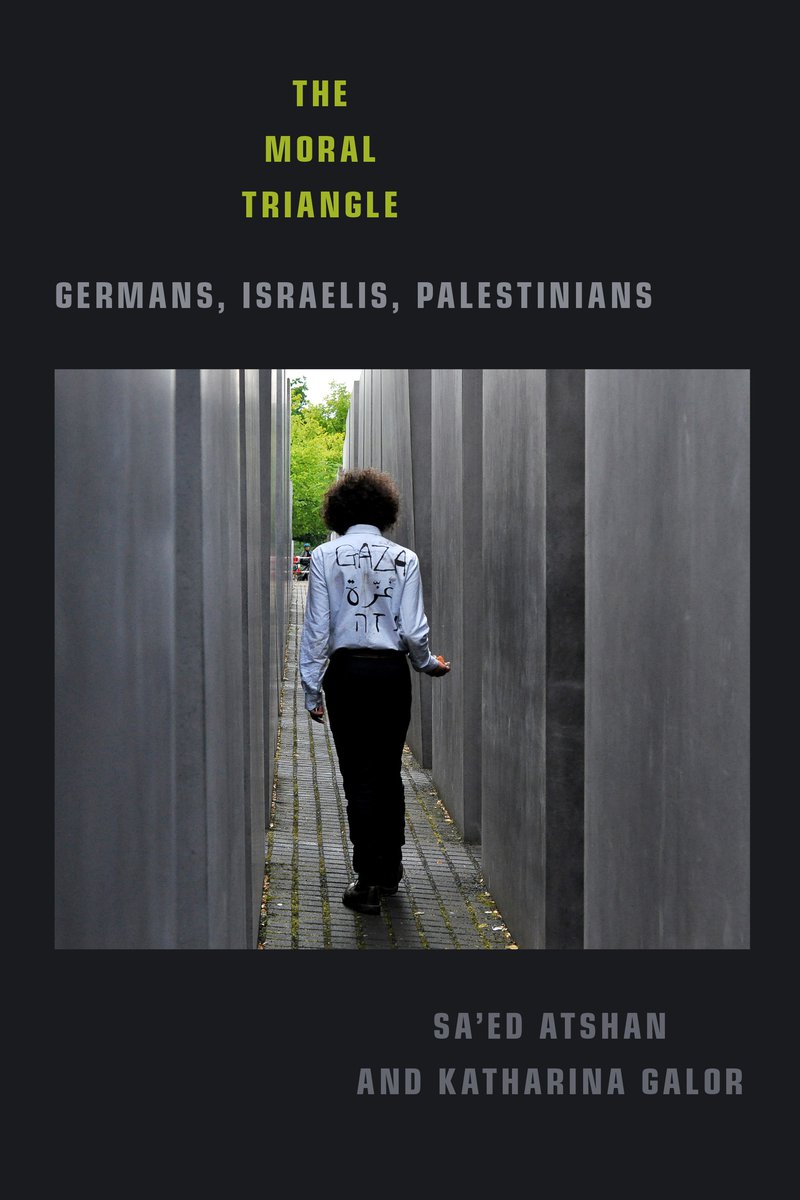

In summer 2020, Sa′ed Atshan, and Katharina Galor will publish the book “The Moral Triangle: Germans, Israelis, Palestinians” with Duke University Press. The two authors present over 100 interviews with Germans, Israelis and Palestinians, exploring their difficult, complex relationship with both past and present. The book examines historical and social narratives in order to understand the special condition of these three communities living in Berlin. Atshan’s and Galor‘s is the first book that tackles the Israeli and Palestinian communities in Germany in this context.

Tugrul Mende: You come from two very different professional backgrounds, how did you meet in the first place and decide to write the book together?

Katharina Galor: I met Sa′ed during the last Gaza war in 2014. I had just returned to Brown University after spending the summer in Jerusalem, to teach in the fall semester. At the time, Sa′ed was a post-doctoral fellow, and he was invited to speak on a panel about the repercussions of the war. I was extremely impressed by him. He was the only junior panelist, all the others were senior scholars. I felt that he intellectually dominated the panel, I thus decided to walk right up to him and so we talked a bit. A week later, a Palestinian friend of mine and a Jewish friend of Sa′ed decided to bring us together and invited us to meet in a tea salon. We very quickly became friends as we realized we had so many common interests.

We came from completely different disciplines - I am an art historian and archaeologist, Sa′ed is an anthropologist. We both had worked in Israel-Palestine and specifically about the conflict. We were very much interested in our respective research. Sa′ed, for instance read my last book on Finding Jerusalem, and I became familiar with his work. We had planned for some time to eventually work on something together. Even though I am Israeli and he is Palestinian we think very similarly about the conflict. It was about four years ago, when my husband was offered to serve as the president of the American Academy in Berlin that I moved with him to the city. I used this period to apply for a few fellowships, and also taught at the Humboldt University. This is when I learned about the very recent Israeli migration to Berlin and became fascinated with the topic and the fact that it was this city of all places that attracted this community. I also found out about the much more significant Palestinian community, and suggested to Sa’ed to write a short paper on this phenomenon which seemed very intriguing. For a little bit over a year we just kept following the media coverage as it relates to these two different but linked phenomenon, in the Hebrew, Arabic, German and English press.

We were shocked that nobody had touched the subject before us.

We were also interested in the Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coping with the past), the role of the Holocaust, and the Israel-Palestinian conflict. We also began to dig up all the scholarly literature that dealt with the relevant topics. In 2018, Sa′ed joined me for five weeks in Berlin to conduct interviews with Germans, Israelis and Palestinians. We were so absorbed by the project and topic and we felt it was so important, and novel, that we were shocked that nobody had touched the subject before us. It seemed very logical and imperative that it needed to be explored: this triangle situation. And then, we just kept writing, writing, and writing, and suddenly there was a book manuscript.

Sa′ed Atshan: As far as our different professional background is concerned, I think it is also important to emphasize that we share much in common. We are both academics and we both are deeply committed to scholarship and to research. When it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as Katharina was mentioning before, we share very similar politics and approaches to our understanding of the conflict, ethics and political contestations that are relevant. We have much in common and that allowed us to share a passion, and be able to collaborate and produce this book, we hope, quite successfully.

TM: What is the book actually about?

Sa′ed Atshan: Our central question is regarding Germany’s moral responsibility towards Israelis and the Palestinians inside its borders at the present moment. We are looking at the Israeli diaspora community in Berlin specifically, which is one of the largest Israeli diaspora communities in the world. We are looking at the Palestinian diaspora community in Berlin too, which is double the number of the Israelis and the largest Palestinian diaspora in Europe. We examine the German population as well and the relationship among these three communities, the points of intersection, as well as divergences and perspectives on moral responsibility and how these communities relate to one another.

TM: How did you come up with the title “The Moral Triangle”?

Sa′ed Atshan: We are inspired by the work of Noam Chomsky. He has a seminal book to think about the U.S. as a super power called “The Fateful Triangle”. But Germany is powerful as well, the most powerful country in Europe, and it shapes Israel/Palestine, and has large contingents of Palestinian and Israeli populations in its borders. Historically, Germany is very much connected with the conflict; in many ways, it has shaped Israeli-Palestinian relationships, and continues to do so. There is so much on the role of the U.S. in terms of scholarly literature but we argue that we do need to look into the role of Germany as well. We believe that we need to think about morality, not only what’s at stake intellectually, but morally as well.

Katharina Galor: We used scholarly books that have examined the Palestinian migration to Berlin, the communities that live in the city. There is currently less on the Israeli migration as it is a more recent phenomenon. There are many articles and several books in process, that haven’t been published yet. But, it has clearly become a hot topic both in the media and in academia to write about Israelis in Berlin. We consulted everything that was available in print or online, and we then conducted roughly 100 interviews: one third Germans, one third Palestinians, and one third Israelis. For half of these interviews, we used questionnaires, and conducted semi-formal interviews. For the remaining 50 interlocutors, we engaged with them without following a questionnaire. We then put these interviews and citations into a theoretical and historical context.

Sa′ed Atshan: We used what is called in Anthropology “deep hanging out” with the exploration of the city, meeting in people’s homes, in cafés, going to the theatre, watching relevant films and plays. For instance, we enjoyed attending the Jewish Film Festival in Berlin.

TM: How difficult was it for you to find participants for this research project?

Katharina Galor: I spent a little bit over a year in Berlin before Sa′ed joined me. I had a few Israeli and Palestinian contacts before he arrived. Shockingly, it was Sa′ed, who never in his life had been to Germany before who then through the use of social media – Facebook primarily – was able to arrive in Berlin with an eight page long list of contacts. There was a snowball effect: once we started to conduct interviews, more and more people wanted to be interviewed. We very quickly had far more interlocutors than we could take on. We wanted to stop at 100 interviews as we had limited time, and both of us had to return to teaching during the fall. We had countless fascinating encounters in the city. As a Hebrew speaker, I sometimes had people share with me very private thoughts and interesting perspectives, and the same was true for Sa′ed. A lot happened in cabs. Sa′ed had several interesting conversations with Palestinian cab drivers or access to a young woman who was an AfD supporter. One thing that was important to us, was also not to bias our work and the results towards friends that are close to our own world, mainly the academic, but also to incorporate interviews with people from all sectors of society, ranging from unregistered refugees, to interviews or encounters with politicians, and numerous prominent individuals of the Berlin and German public.

TM: Did you have any difficulties while you conducted research for the book?

Katharina Galor: There were a few individuals who refused to be interviewed because we were an Israeli and a Palestinian working together. But generally speaking I feel that people felt comfortable talking to us and opened up, and were willing to talk about very sensitive issues. They seemed to feel confident that we would treat the interviews and data confidentially, which we did of course. Out of the 100 people we interviewed, only four or five agreed that we mention them by name.

For someone who lives in Germany and is employed in Germany, many of the issues we touched upon are too sensitive.

I think they also felt that questions we asked and the topics we touched upon were highly relevant for many of the individuals we interviewed. It is a topic that holds a significant place in the lives of the people we spoke to. Yet, it is also somewhat a taboo. For someone who lives in Germany and is employed in Germany, many of the issues we touched upon are too sensitive. Since neither of us is working at a German university we felt we could engage these issues, and I think our interviewees somehow sensed that. People either intuitively, or because they deal with these questions, understood that this research was daring and extremely sensitive. But, we were outsiders and therefore we were able to tackle what a lot of people think about but don’t dare discuss and engage with openly.

Sa′ed Atshan: The heart of our book is mainly related to the Holocaust, anti-semitism, islamophobia, anti-Arab racism, the far right in Germany, issues of historical guilt, and censorship, specifically of Palestinian voices. These issues are controversial in German public discourse. It requires a lot of courage to speak openly in this respect.

TM: Did you find any similarities while speaking to Israelis and Palestinians living in Germany with those living in the U.S.?

Katharina Galor: I think this situation of Israelis who settle in Berlin is very unique because of the history and because of Germany’s responsibility towards the victims of the Holocaust and the related Vergangenheitsbewältigung, not to mention the very prevalent guilt feelings. I think the relationship between Germans and Israelis in Berlin is highly unusual. Israelis on the one hand feel that living in Berlin makes things quite easy from an economic point of view. There is a lot of governmental funding to support entrepreneurs, and intellectuals, which makes their absorption into German society relatively easy. With regard to Palestinians in Germany versus Palestinians in the U.S., I do feel that there are a lot of parallels. I think the difference is the very special treatment that Israelis and Jews who live in Germany receive, and the very strong commitment of the German state to the state of Israel. This highly privileged treatment, makes the situation for Palestinians in Germany more difficult than the situation in the U.S. There clearly is more censorship in Germany.

Sa′ed Atshan: I agree with Katharina, there is censorship in the U.S. and it’s really bad, but the fact that it is really worse in Germany shows you how bad it is. In Germany, there was a high number of people, especially Palestinian Germans, who fear that if they speak openly about their identity, about Palestinian human rights, or utter critique against Israeli occupation, this would be an existential threat for them socially and politically. They would lose their jobs, and their place in the public domain. This causes significant anxiety.

A lot of Germans felt that if they showed solidarity with Palestinians and if they openly criticized Israel, they could loose their jobs.

Katharina Galor: This was something that many Germans, including at the highest levels of the social and professional spectrum we spoke to felt. A lot of Germans felt that if they showed solidarity with Palestinians and if they openly criticized Israel, they could loose their jobs. This was very striking in our interviews. Germans felt very uncomfortable with the way Israel was treated in the public discourse. Many of them felt they could risk their professional and social standing if they would talk openly about the Israel-Palestine conflict.

To come back to one of your earlier questions, we emphasized how much we think alike on politics and on everything we worked on in the context of this book. I want to emphasize, despite the fact, that I grew up in a very Zionist context with a strong commitment to Israel, and Sa′ed grew up under the occupation. Despite the fact that we grew up in societies that really imposed on us to think of Israelis and Palestinians as two binaries, as enemies, despite the wall that separates us, and despite the idea that we belong to different nations, we both felt very strongly that we really should overcome those artificial boundaries, the imposed borders, and the identity constructs. Sa′ed feels Palestinian, and I feel Israeli, but yet we were able to agree on everything that we worked on in the context of this book.

TM: Did you find any difficulties in finding the right publisher?

Sa′ed Atshan: As soon as we contacted Duke University Press, they responded enthusiastically and immediately and we were absolutely thrilled to work with them. During the discussions and editing, they shared that they were surprised that no one had ever written this book yet.

Katharina Galor: The committee who decided about our proposal unanimously supported the idea of publishing the book. And the two anonymous reviewers also seemed very enthusiastic. It was a very fast and smooth process.