What would become of a city without stories? It would certainly lack luster and memories, even if the stories it would have told were filled with pain and the stench of loss and inconsistencies. The stories of a country are the secret tales of its people, and cities are mirrors reflecting people’s souls, according to Shams al-Din Tabrizi. Accordingly, the more numerous the lives lived by the people and their country, the more diverse the narratives and major incidents shaking their histories politically, socially, culturally and existentially.

And, with successive changes and upheavals in creativity come deeper and more rooted questions about existence.

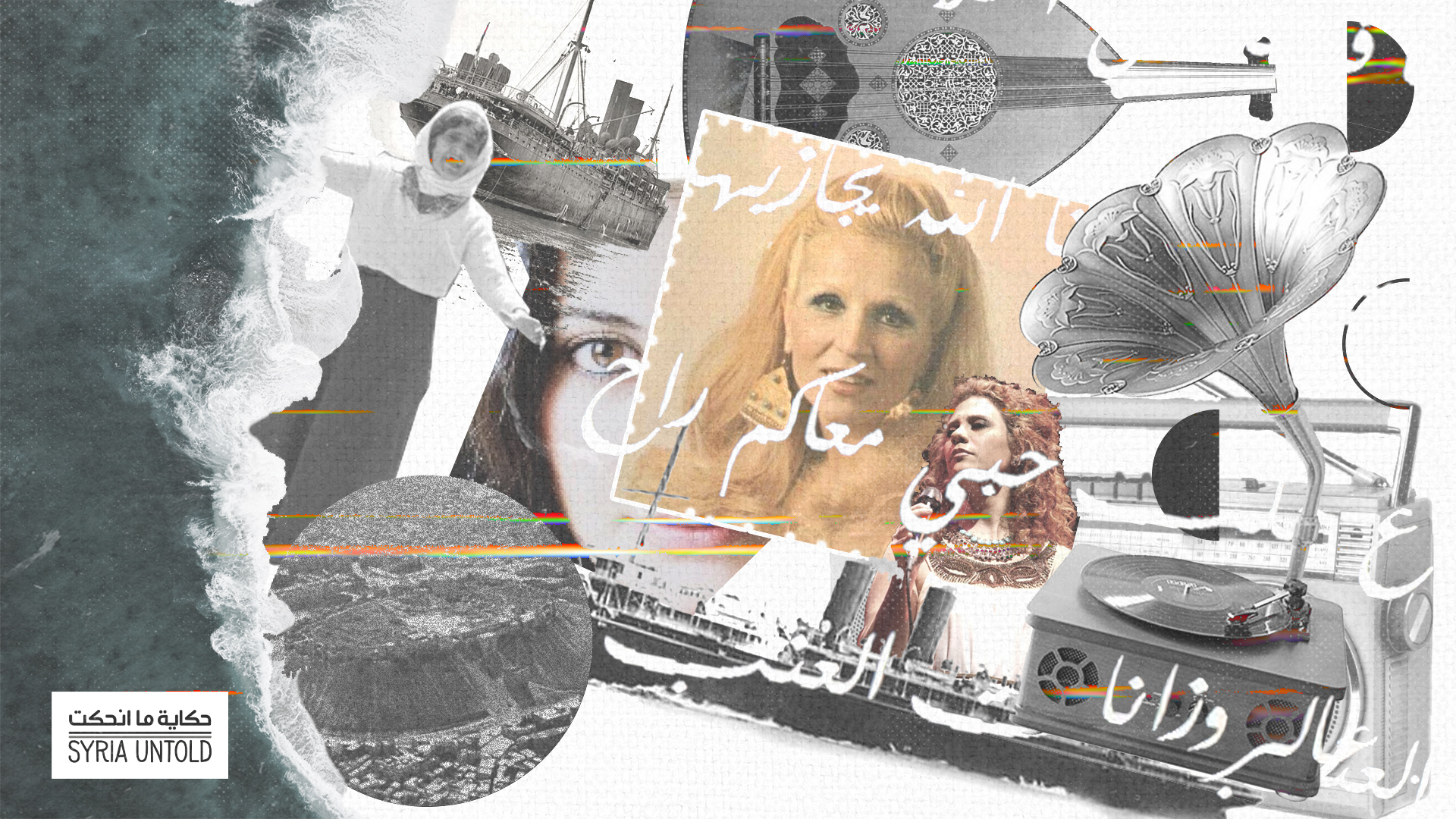

In this series of articles, we attempt to pose several questions that do not have ready and obvious answers—questions about past and continuing change in Syrian narratives after half a century of deep transformation in Syrian society, from the early days of the military dictatorship to several shocks; most recently, the revolution, war and forced displacement, which perhaps won’t be the last. That change resembles a long golden chain made of intertwining loops. Each loop affects the next and is equally important and influential in its time and circumstance. We will attempt to ponder the indications of change and its beginnings which preceded the latest shock. We will tackle the revolution in narration, or the cultural revolution, if we may, which preceded in one way or another the social and political revolution. It was a revolution of form and content and of narrative/fictional techniques used and meanings relayed; a revolution in the proliferation of female novelists, whether their writings were feminist or non-feminist, and in the growing talk about minorities, be they ethnic, gender or religious/sectarian, and about pluralism in its proliferative, democratic notion. Tackling such topics in the past was almost prohibited due to the influence of several prevalent ideologies.

Raqqa, at the center of the universe

16 August 2020

Lina Barakat: ‘I want to be a participant in this change’

21 December 2020

Was this phenomenon merely a “verbal outburst” or a “lust for speech,” after decades of silence and oppression and past exigency of using codes and double entendre out of caution? Or was it more of a lust for telling a blacked-out and repressed story—a shadow story that remained stuck in throats and hearts for long decades? Was it the result of direct political implications on literature, since politics under dictatorships is objectively and tightly linked to narratives? The attempts of Syrian narratives to break the political taboo constituted a real revolution before the 2011 revolution, when prison literature came to light, as well as writing about massacres and telling the details of personal and painful stories of people living under dictatorships.

After 2011, the narrative change deepened and appeared through the altered essence of the characters in the stories; thus reflecting the prevalence of documentation and attempts to preserve the memory from oblivion. There was a change in content and its underlying variation, based on a radical upheaval of society horizontally and vertically, politically, economically, socially and geographically. But, was there in return a significant parallel change in the structures of the artistic/technical stylistic form? This is a major question that can be posed. Perhaps it is too soon to delve into all the recent changes in Syrian narratives, and maybe critique will need some time to decipher the huge amount of narratives written in the past years. But, transforming creative writing is always slower, as is understanding its deeper meaning, as opposed to the rapid unfolding of political writing and its rules.

Accordingly, opposition in its political sense is certainly not enough to create a political product. Besides, not every opposition writer is necessarily a creative genius presenting new material, but opposition in itself is an act of freedom. It is saying “no” when you are expected to say “yes.” In light of this, opposition in its deeper human, rather than political, sense is a type of creativity, but it is not enough to produce new narratives in the creative sense. What created this discrepancy between the products of narrative creators based on opinions, inclinations and stances? Is there any real difference in the Syrian narrative product?

With time, after 2014, a new bitter thread was added to the Syrian narratives. It was related to departure, displacement and asylum and constituted one of the major shocks to the human story; stirring new questions that took center stage and had to do with identity, belonging and the current reality. Questions surfaced about exile and a new country, the difference of cultures and perspectives, and how to restructure questions/axioms through the eyes of others. Based on the idea of looking at ourselves in the others’ eyes, a new-old question arose: What are the boundaries separating particularity from universality? The harbingers of this question surfaced a few decades ago, when the wave of translation into Arabic started and Arab and Syrian literature opened itself to global translations.

This question puts us face-to-face with various challenges. How can we maintain the particularity of our narratives without identifying with others’ narratives—all while remaining connected to the new recipient/the other and the global creativity movement? This dilemma gives the impression of walking on a tightrope hanging above the abyss.