Day 8,894 of Bashar Al-Assad’s rule in Syria, and Day 412 of the Israeli genocide of the people of the Gaza Strip

“How can a Syrian maintain their sanity in this madness? Unfathomable levels of madness! How can anyone, in general, maintain their sanity in this madness?”

With this rhetorical question, Syrian leftist thinker Yassin Al-Haj Saleh concluded his intervention during a cultural evening in Berlin on 22 November. That night, I sat amidst a scattering of empty chairs, except for a few attendees who had come to commemorate the nearing fortieth anniversary of the passing of Lebanese writer Elias Khoury. The journalist, academic, and novelist passed away at the age of seventy-six, mere days before the Israeli war of genocide against the people of the Gaza Strip escalated and military operations extended to Lebanon, specifically on 15 September.

“At that moment of political abyss,” as Palestinian researcher Himmat Zoubi described it, the Febrayer Network and the Syrian Al-Jumhuriya website sought to highlight Elias Khoury’s cultural and militant legacy. This legacy offered a pioneering model for documenting the memory of the Palestinian Nakba beyond official history books, relying on the voices of his contemporaries through oral history techniques. His literary works, as described by the speakers, “offered an organic model that interconnected Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria as a trans-geographical region unified in its struggle against the tyranny of Baathist rule and the Israeli occupation,” further characterizing it as “a region greater than the mere designation of ‘Middle East.’”

The First Hours: Syria Without the Escapee - "Forever is Over"

The post circulating on social media, written by al-Haj Saleh, was accompanied by a photo of his wife, Samira Khalil, along with activist and lawyer Razan Zaitouneh and other supporters of the Syrian revolution who were kidnapped at the end of 2013. It was the first thing I read on social media in the early hours following the news of the dream—the impossible.

For the ten days leading up to its realization, I lived in a state of waiting, overshadowed by disbelief that it could ever come true. From our living room in Berlin, my Syrian husband spent sleepless nights in front of the television, on the phone in constant calls and messages, following the liberation of one Syrian city after another from the grip of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. He was astonished by the rapid pace of events and gripped by fear of the “division of the country,” a country his feet had not touched in ten years.

Like millions of Syrians exiled after 2011, he had been forced to suppress a flood of memories of his homeland—his neighborhood, his home—and reconcile with the impossibility of visiting it under Assad’s rule. This, he confessed to me for the first time, as he hugged me and we both wept when the news was confirmed: “Bashar ran away!”

Day One: Syria Without the Escapee - "We Are Coming Back"

This was the first and last phrase repeated at the same moment by two young Syrian men who walked quickly toward each other before embracing tightly and sobbing. Their cries reached me where I stood next to them, a small dot in the middle of Oranienburger Platz in the center of Berlin, visible from a drone only because of the Egyptian flag draped over my back, distinguishing me within the vast sea of people carrying the flags of the Syrian revolution.

I was not the only outsider among the thousands of Syrians flooding the streets of Berlin—whether on foot, using public transportation, or in private cars honking their horns in celebration. Songs by Abdul Basit al-Sarout blared from cassette players as the crowd rejoiced in the victory.

“I lived in Syria for three years,” I heard a blonde woman say in English to her companion as they passed by me on a side street near the demonstration. In German, a man in his fifties told his companion, “There are more than a million Syrians living in Germany.”

Berlin that day felt like the embodiment of the Facebook page titled The Capital of the Syrians in Germany. When I refer to the Syrians in the diaspora, I mean “the Syrian mosaic,” a term Assad used in his sectarian-tinged speeches during his war on terrorism—an expression that Syrians often mocked in my conversations with them.

Every event, every scene, and every story we documented added a new layer to a collective memory burdened with trauma.

This ranged from the group of veiled women I met on the metro, who exchanged smiles and congratulations with me, saying, “Congratulations to all Muslims,” to one of my acquaintances, a civil society expert and member of the LGBT community. Her face was swollen, and she hugged me tightly in the middle of the street, saying, “No one should ever say that Syrians can’t achieve anything anymore.”

Upon reaching the square, where those ecstatic and longing for such overwhelming joy were gathering, I found myself moving like an almost invisible dot among thousands of Syrians who formed intersecting circles. In each circle, voices rose with chants and songs that had their own distinct character.

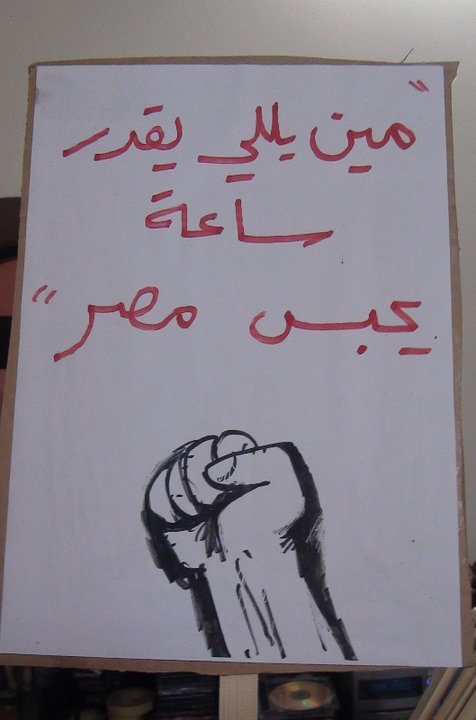

In one circle, the chants of the familiar Joufiyeh dance from southern Syria and the Arabian Peninsula rang out loudly, so I moved on to another. There, young men on shoulders chanted with all their might: “Damn your soul, Hafez,” a chant I had often heard during demonstrations supporting the Sweida movement that erupted in August 2023. In yet another circle, the crowds chanted in unison: “Raise your head high… you are a free Syrian.”

What felt unfamiliar to me, an outsider Egyptian, was almost unbelievable to my Syrian companions: songs of the Syrian revolution, Abdel Basset al-Sarout’s “Jannah Jannah” being hummed by Arab-looking teenagers who spoke to each other in German as they exited the metro car, and Samih Shukair’s “Ya Haif” playing openly on the streets of Berlin, even on restaurant screens as we waited for our hot meals at the end of a day of celebration. For them, the moment was more than just a celebration; it was a loud and symbolic declaration of Syria’s reclaiming.

On my way home, scrolling through social media, I came across a Facebook post by a Syrian writer based in Berlin. It resonated with a quote from Syrian-Irish writer Suad Al Durra, who told The Irish Times: “In that moment, I realized that we are no longer refugees or displaced people. We are free, and we have a homeland to return to—to show our children that Syria is not a fantasy place.

Day 5: Syria Without the Escapee - "Back to Life"

These three words came together in an attempt to capture the moment when tens of thousands of Syrians gathered in broad daylight, under the bright sun of Damascus, forming a circle in Umayyad Square with the towering Mount Qasioun behind them. This description accompanied a photo circulating on Facebook of the crowds in the Syrian capital. I was reading a comment on that photo: “Really, our spirit has returned.”

While I was deep into reading the comments, I finally received a response to my message checking on one of my acquaintances in Damascus, a young woman in her mid-twenties. I had met her on my first trip to Syria a year and a half ago, learning about her family’s displacement from Idlib to Sweida, and how she had been trying to start over as a Sunni student wearing the hijab in a city with a Druze majority. She had later moved to Damascus to continue her university studies and work. Her message read: “Good evening, Basma... I'm sorry, but you know; celebrations…”

Day 2: Syria Without the Escapee - A Glimpse into the Hell of "Others"

I had just left my office for a short break from following the flood of comments on Facebook from several of my Egyptian acquaintances. They were commenting on the overwhelming joy of Syrians all over the world, while also expressing pessimism about a future ruled by Islamists, in a country that would be divided along sectarian lines like its neighbors Iraq and Lebanon. As one journalist put it: “Bashar is finally gone... but the future in Syria is foggy.”

A Facebook post by Egyptian writer Khaled Mansour reflected on the reactions of some Egyptians to his own Syrian joy.

I pushed open the door to the living room, where the revolutionary tent my Syrian partner had set up in front of the TV screen had not been taken down as the “Deterrence of Aggression” forces advanced. It remained in place even after Bashar al-Assad fled, when he shouted at me to leave: “You won’t be able to bear seeing these pictures,” referring to the live media coverage from the hellhole known as Sednaya prison.

About Sednaya Prison and Our Documents

29 December 2024

In an attempt to lighten the moment, I joked: “You know, I’ve lived through a lot of drums beating on my head.” Although I had certainly not witnessed anything similar during my field journalism work in Egypt between 2011 and 2016, his warning about the impact of the images and testimonies coming from Sednaya took me back more than fifteen years, to October 9, 2011.

I now see before my eyes that a 22-year-old new journalist, coming from the provinces, who had only been working for a few months at one of the largest private Egyptian newspapers in Cairo. She was sitting in front of her laptop at a long table that shaped the square room, with journalists to her right and left, and her back to a newsroom crowded with editors holding their phones to follow the news coming from correspondents on the ground about the Copts gathered around the state radio and television building (Masper) in downtown Cairo, to denounce the repeated attacks on churches.

In an attempt to connect the scattered words on the tongues of the editors, recalling what the correspondents on the other side of the cell phone lines were transmitting in real-time coverage of the events, as a peaceful demonstration turned into a clash with the army forces, I began browsing social media. I saw pictures and videos of corpses, human remains, and traces of blood on the walls, around the massive building overlooking the Nile Corniche—land I had once walked on during a journey in search of an opportunity to work as a journalist before 2011.

Fahmy explained that the way the Egyptian regime and a segment of the people dealt with the January Revolution as if it had not happened can be understood within the context of shock. He explained that societies that experience trauma tend to freeze and pretend the pain does not exist because facing the source of the pain directly is more difficult than they can bear.

A kick in the stomach and suffocation—that’s what I felt before she rushed to the bathroom to throw up. But I didn’t vomit then, nor did I after, despite all the scenes of violence that followed in Egypt after 2011, either as a journalist or as a citizen. In that luxurious marble bathroom, I swallowed my “shock” and returned to the newsroom, jostling with other journalists to secure urgent statements from “political” analysts and “revolutionary” activists to comment on the “events” that were recorded in Wikipedia history—once under the “Maspero Massacre” and another time under the “Maspero Events.” In both cases, 28 Copts were killed, 12 of whom were confirmed to have been run over by army armored vehicles, and seven shot in the chest or head, while 200 others were injured.

Day Five: Syria Without the Escapee - "Syrians, a Scoop!"

Since the news about Assad's underground hell began to unfold on the second day of his escape to Russia, I don’t remember us turning off the TV screen hanging on the living room wall in the following days. That was until I saw the report from the Al-Hadath correspondent, wandering around in her elegant black outfit with high heels like nails, sweeping away the shabby clothes of the detainees lying on the ground and hanging on the walls of the cell.

That "exclusive tour for Al-Arabiya channel inside one of Assad's prisons" was followed by another report from in front of Sednaya, with former detainees. The Syrian correspondent, dressed in modest winter clothes, asked them "to describe to him in detail what their experience of torture was like."

Syria, which had been a closed bottle for years to Arab and Western media, with the exception of a few war correspondents, had turned overnight into a “Mecca.” Its streets and cities, liberated from Assad’s grip, had become a pilgrimage site for countless “parachute/balloon correspondents.” I had learned about their existence and disappearance in the international press market from a British lecturer and former BBC correspondent while studying for a master’s degree in war and conflict journalism in the UK years ago. But here they were, suddenly descending to cover the “Syrian story,” while local Syrian journalists, who had risked so much to tell the world what had been happening since 2011, disappeared into the background of Syria’s story-making process, as Syrian journalist Hussam Hamoud put it.

“They took everything overnight… Foreign media flooded the scene and started writing about Syria as if we didn’t exist. As if our years of sacrifices meant nothing,” one of the Syrian journalists told Hamoud.

This provoked Syrian-Irish writer Suad Al-Durra, who published a post on her Instagram account in English on 12 December. It was a statement in response to the requests of journalists who had flocked to her over the past five days. Their requests focused on three topics they wouldn't deviate from: prisons, returning to Syria, and jihadists/ISIS.

Al-Durra began her post by saying: “I have always used my free voice and pen to share important stories and change the narrative. I have become accustomed to all kinds of reactions or questions that may be racist, insensitive, or naive. But recently, since the recent shocking developments in Syria, I have received many media requests in a way that can only be described as unprofessional.”

“If you’re looking for a random Syrian to finish your assignment for today, I’m not available. And no, I won’t connect you with another Syrian to respond to you,” she concluded her post, which she titled “Syrians Are Not a Scoop.”

Day 14: Syria Without the Escapee – Syrian Stories Are Ambiguous

Miles away from Syria, which is currently preoccupied with the questions of revenge, amnesty, and transitional justice against those who colluded with the Assad family to tighten their grip on the people for decades, my Syrian friend, born to an Alawite family in a village near Hafez al-Assad’s birthplace, Qardaha, was confronting a heavy legacy in the heart of Berlin, among her Syrian university classmates.

“Now you want to be a critic?” This rhetorical question from one of her Syrian classmates ended a heated discussion about a CNN report showing the release of a Syrian detainee who was allegedly a victim of the regime. My friend, who had expressed doubts about the report, was immediately labeled an implicit defender of the regime. It later turned out that the report was fabricated, and that the prisoner was actually a member of the regime’s security services.

As with media coverage of the Syrian story, the stories of the peoples of our region are often lost amid major historical events, or reduced in their complexities to two words such as “Arab Spring,” “military coup,” “Palestinian Intifada,” or most recently “October 7.”

My friend, who is in her thirties and trying to rebuild her life after a dangerous refugee journey to Germany, said to me: “We are supposed to pay the tax twice!” She was referring to her personal suffering—being ostracized by the Alawite community because of her parents’ communist affiliations and imprisonment, and facing similar threats and provocations due to their sectarian background, just as others from the Alawite community have recently experienced.

“I thought that when the injustice goes away, the stories will become clearer!” she added after a moment of silence. “I understand when someone’s accent causes you a psychological complex,” she said, referring to the distinctive Alawite accent, which has become a symbol of fear or hatred for many Syrians.

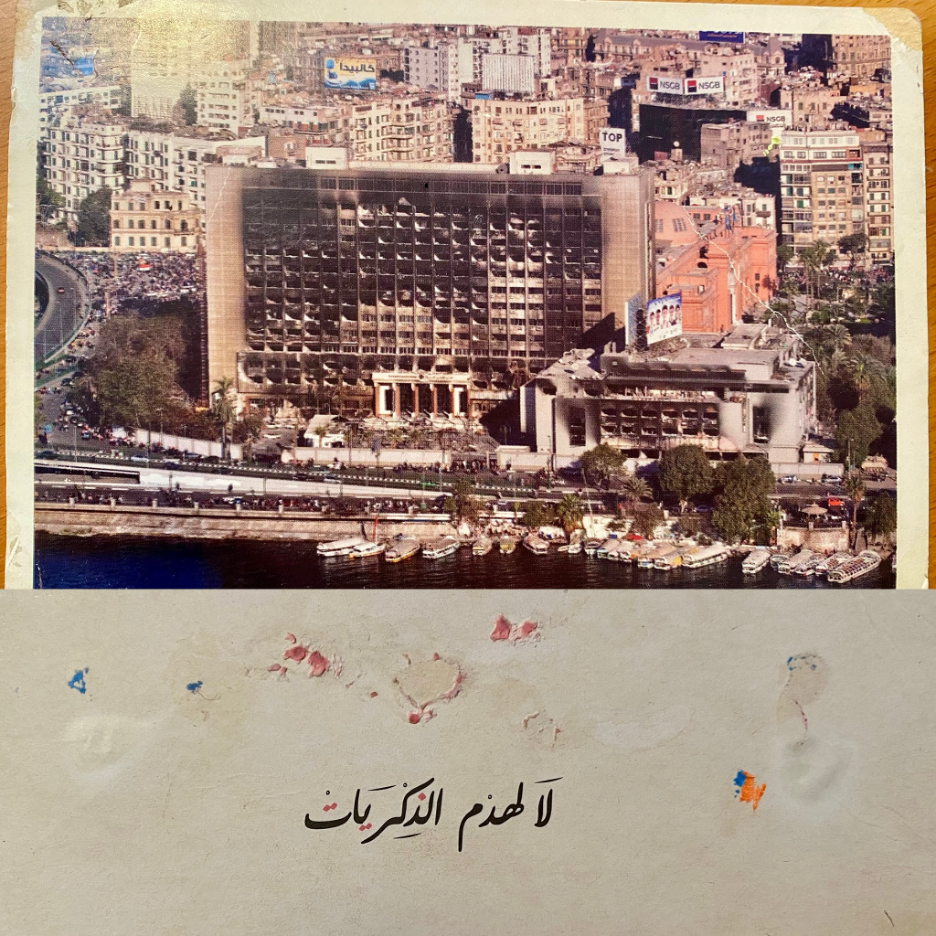

Year One: Egypt Without Mubarak, “No to Destroying Memories”

A postcard I received while attending a symposium at the American University in downtown Cairo, where many cultural events were held on the repercussions of the January Revolution. It shows a picture of the burned headquarters of the ruling National Democratic Party, taken by photographer Mahmoud Khaled. On the other side of the souvenir is the phrase “No to Destroying Memories.”

Year 9: Egypt without Mubarak, Shocked People

I was sitting in front of my laptop screen in my room in Berlin, in an online psychotherapy session funded by an international organization working in the field of protecting journalists. My Lebanese interlocutor explained to me that the incident that happened eight years ago, which I witnessed remotely from the newsroom, is clearly etched in my memory because it is one of the times when I was exposed to what is known as “vicarious trauma” due to my journalistic work.

Like many journalists and citizens in Egypt after 2011, that memory accumulated with other memories—some we experienced directly, and some we witnessed through camera lenses and computer screens. Every event, every scene, and every story we documented added a new layer to a collective memory burdened with trauma. This memory, which concerns Egypt, our generation, and journalism during that period, swings between two extremes: “memories present in all their details” or “total amnesia.”

I was the partner who saw the Assad regime on my bed in Berlin, creeping into my Syrian partner’s nightmares, waking him up in the middle of the night from his slumber.

This description was one I heard in a completely different context when, in June 2023, I listened to a Syrian woman talk about her attempts to rebuild her memory and the memory of five other women regarding their displacement from their villages and cities in the Damascus countryside—Darayya, Zabadani, and Madaya. She spoke about the lost details of their daily lives, and what their homes had looked like before the displacement. These stories found their way into a publication titled “Justice of Place,” accompanied by drawings reconstructing the homes as they remembered them, produced by the Syrian feminist organization Women Now. This was one of the diverse attempts by Syrians to deal with the trauma resulting from years of war and displacement—efforts I have encountered since I set foot in Berlin in the summer of 2017. Some of these efforts took the form of storytelling and group venting.

Circle of Peace: My Syrian Aunts and Our Hammam in Exile

29 March 2024

In contrast, I had not witnessed similar attempts in Egypt before I left in the fall of 2016. More importantly, I did not know at the time that my memory of Egypt during that period was “shocked”—a memory that began in my small town in the Nile Delta, where I participated as a citizen in the 18-day demonstrations, far from the lights of Tahrir Square, and then extended to Cairo as a field journalist from March 2011 until my departure.

My “shocked” memory of that era is not entirely miserable, but it is limited to the two extremes. There is no gray area in it. It feels as if life had only two colors: the euphoria of victory, or as the Egyptian journalist Ahmed Ragab, who resides in Berlin, described his experience to me in one of the most prominent Egyptian newspapers at the time: “At one moment, we were very strong and touched the roof of the whole world,” and then the bitterness of defeat and anger.

As for Egyptian society, apart from the press and journalists, it too was going through a state of shock, according to the analysis of Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy, whom I met in the fall of 2018 at an event organized by the House of World Cultures (HKW) in Berlin to discuss the relationship between archives and the Arab revolutions. In an interview I conducted with the former head of the Egyptian Revolution Documentation Committee for the Egyptian website Al-Manassa, Fahmy explained that the way the Egyptian regime and a segment of the people dealt with the January Revolution as if it had not happened can be understood within the context of shock. He explained that societies that experience trauma tend to freeze and pretend the pain does not exist because facing the source of the pain directly is more difficult than they can bear.

Fahmy identified two main sources of pain in Egyptians’ relationship with the January revolution: the first was the damage to the financial and commercial interests of a large segment of the population, which the state sought to “glocalize and magnify.” The second was the discovery of deep divisions among members of society due to the openness of the public sphere after the revolution. “People spoke and expressed opinions that had not been heard before from all sides,” he said. This fear of difference, he believed, hindered our ability to see the commonalities between us, even though Egyptian society enjoys a high degree of homogeneity compared to countries in the region such as Lebanon, Syria, and Libya. However, as Fahmy pointed out, this homogeneity was not enough to overcome the effects of the shock.

Syria 2011-2024: From the Breaking News Ticker to My Imaginary Memory

"Mass demonstrations against Assad," "chemical weapons against civilians," "civil war," "elimination of ISIS," "refugee crisis" — these headlines, and many others, have alternated their positions at the bottom of the breaking news ticker on television, whether on Arab or international channels, accompanied by images that shake the body. These headlines and images have shaped our memories, as people who are not from Syria, of the country over the past 14 years. Each one represents an important chapter in the story of Syria after 2011, but they were quickly replaced by new headlines. Without the need for New Year's prophecies, other momentous events will soon follow, such as the "conquest of Sednaya."

As with media coverage of the Syrian story, the stories of the peoples of our region are often lost amid major historical events, or reduced in their complexities to two words such as “Arab Spring,” “military coup,” “Palestinian Intifada,” or most recently “October 7.” I experienced this myself as an Egyptian citizen who participated in the 18-day demonstrations, when the American Times put us on the cover of its magazine “The Generation That Is Changing Egypt,” and I lived it as a journalist covering turbulent moments such as the Rabaa Al-Adawiya sit-in, and it happened to me as an Arab immigrant, when I sat in front of German television screens in Berlin watching their coverage of the war of extermination in Gaza.

Syria under Assad’s rule carved its place in my memory through the stories of the Syrian men and women who passed through my life over the past six years, laden with contradictions of life and death, resistance and evasion.

What I later realized is that part of this superficial interaction goes back to what I experienced in newsrooms 15 years ago, when none of my colleagues cried out in horror at the images we saw of the Maspero events. The news came to us as if it were “the pain of others,” which we had to record and turn into abstract numbers: “dead and wounded,” in a frantic race with other news sites for speed of publication. The phrase that explained my feelings at the time I did not find until years later, in the winter of 2017, in the library of my British university, when I was reading a book required in my specialization in covering war and conflict, On the Pain of Others by the American journalist Susan Sontag.

I didn’t realize it at the time; I was inside the event, the news I was covering, and inside the bigger event, Egypt after 2011. But I didn’t leave that big event until after I left Egypt in 2016. I carried in my suitcase a New York Times clipping with my traumatized memories and didn’t open it until I met Syrian women in Berlin at the Peace Circle for Psychological Support for Arab Female Immigrants in 2018. Then began an extended journey of several attempts to return my soul to my body: I feel everything I didn’t allow myself to feel, I create coherent stories from the scraps of my memory about the past, and I share them with others as I do now, in an attempt to weave another memory, about what happened in the past, and the future that is before my eyes, and the present, present in it with all my senses, as much as possible.

But the luxury of having a distance to remember and tell was not available to me in Egypt. I was inside the accelerating events, living them as an ordinary citizen, and as part of a daily media machine. In other words, I was orbiting in a successive orbit of shocks that struck Egyptians in the post-2011 period.

As I later realized the impact of major political and social transformations and their personal imprints on me, I found myself in a strange position when Syria disappeared from the breaking news feed in the past few years. Syrians, both men and women, were left alone with the impact of those major events on them, and here I met them!

Protests in Sweida: From First Bread to Last Freedom

09 October 2023

My position was not fixed as I witnessed the imprints of displacement, war, and division intertwined with attempts to restore Syrian life with all its cultural and social details in exile. I was writing, listening, reading, and observing, moving between different roles. Sometimes I was the journalist and researcher in the cultural and social life of Syrians in Berlin, and other times I was the friend who shared the sofa of her Berlin home with Syrian friends, weaving intimate stories with flowing tears about the homes they had been forced to leave in Damascus and its countryside, and longing for the lives they had left behind, or families stuck there. And sometimes, at other times, my position was more intimate. I was the partner who saw the Assad regime on my bed in Berlin, creeping into my Syrian partner’s nightmares, waking him up in the middle of the night from his slumber.

Before I approached this world, I was just a passerby among the Syrian immigrant communities in Berlin; I got to know them from afar, through the sectors of culture, arts, journalism, and civil society. Over time, imaginary touches began to form in my mind about Syria. Touches created by their food that I tasted, their dialects that I learned to listen to, their media that I consumed in exile, and their Aleppo’s “Qudud” that accompanied me in musical evenings that recalled Syria in exile. Thus, Syria under Assad’s rule carved its place in my memory through the stories of the Syrian men and women who passed through my life over the past six years, laden with contradictions of life and death, resistance and evasion. I did not know, until recently, that these stories that I was told about Syria or that I read and heard about had created a kind of imagined “vicarious memory”.

This type of memory is also formed by hearing family stories around the dinner table, where stories are woven across generations. As American psychologist Robyn Fivush has concluded in her research on family stories, this type of memory has a profound effect on family members because it provides them with models or insights into how the world works and how they fit into it, especially during times of great events. In her studies of families who talked more openly and collaboratively about difficult experiences after 9/11, Fivush found that children from these families were less likely to have behavioral problems, depression, and anxiety, and showed fewer symptoms such as anger or substance abuse.

These stories that I was told about Syria or that I read and heard about had created a kind of imagined “vicarious memory”.

In an interview with the Hidden Brain podcast, Fivush argues that listening to others’ struggles within the framework of “participatory storytelling” seems to help us become more resilient in the face of adversity. Isn’t that what I personally experienced in June 2023? At the height of despair, nine months after the genocide against the people of the Gaza Strip, and 13 and a half years after the Syrian Odyssey, with no hope of removing Assad from power, I found myself among dozens of Syrian men and women at the Febrayer Network headquarters in Berlin, gathered to hear the stories of Syrian women displaced from the Damascus countryside in late 2016, including Yasmine Sharbaji from Daraya, from the “Families for Freedom” group demanding the disclosure of the fate of the forcibly disappeared, who spoke of what they described as “the homeland” that Bashar al-Assad’s barrel bombs had leveled to the ground. There were many tears and moments of silence over the loss these families had endured, but at the same time, “as you hear their stories, you can’t help but feel their enthusiasm,” said Syrian novelist and physician Najat Abdul Samad, who moderated the launch of Justice of Place. The book was an attempt to “bring together families,” and to create an “unimagined” memory of life before displacement.

“When women talk, they talk about everything. When women from the same place talk, they create a collective memory for this place, and show another face of justice, until the time comes to hold the criminals accountable,” that was what resonated that day.

Amidst those Syrian stories of trying to restore lost justice, this was the first time I thought about my Egyptian memory of Syria, and the stages of its formation: from scattered retouches to an imagined memory, then to a semi-imagined memory of life under Assad’s rule, attempts to escape, and endless hope for a new beginning and the pursuit of justice. I did not have the luxury of retrieving and rebuilding memories except in my position amidst the forced exiles of many Syrians at the time.

A year and a half ago, I had another luxury that many Syrians, including my husband, do not have: visiting Syria. The visit, which I wrote about part of under a pseudonym at the time, was a new and realistic chapter in my memory of Syria, and a test of the strength of my "imaginary" memory woven by the stories of Syrian men and women, specifically when I crossed the road extending between Sweida and Damascus, barren except for a few olive trees.

For the first time since I set foot in Syria at my husband's family's house, I was alone. I felt the weight of all the stories that made up my imagination about Syria. From my seat, and from behind the glass, all my Syrian friends and acquaintances gathered on both sides of the road. I saw them standing on their land, rooted in it like olive trees. I cursed the soul of Assad and his sons Bashar and Maher with every picture I came across at a military checkpoint on my way to Damascus, while my tears silently streamed down my seat behind the bus driver.

Today, I have the luxury and privilege of following the current moment in Syria, and the ability to enter and exit it, as I left my living room in Berlin, when my husband shouted at me, trying to avoid me seeing the images of Saydnaya. It is a privilege I did not enjoy before when I was in Egypt between 2011 and 2016, and it is also a privilege that not many Syrians who experience all these feelings at once have, as my Syrian friend who has been following the torrent of news flowing from Syria since 8 December repeated to me. While the international and Arab media descends “in a balloon” to cover the Syrian story under titles such as “returning to homes,” the breaking news a few years ago spoke of “displacement from homes.” But few stories are told, about the years that separated them and the endless attempts to regain their souls.

"While Syrians around me are preoccupied with their historical moment, struggling with uncertainty, terrified for their newborn 'freedom,' or as my friend Zeina Ali writes in her Facebook post, 'everyone is pulling each other's hair these days,' I reflect on this situation that I somewhat experienced with millions of Egyptians in 2011 and beyond. I, a non-Syrian, strive to gather the scattered threads to weave and repair my almost imagined memory of Syria. I do this contrary to what I was trained to do in my academic studies of journalism and my journalistic work—reducing and maintaining distance from the event.I try, without the technical tools, because 'what happened should not have happened to the people of Syria or any people,' and it should not be forgotten amid the momentum of the current historical moment. And because I learned from the Syrians gathered at the launch of 'Justice of Place'—when everyone was desperate for the removal of Assad—their saying: 'The rock is not split by the flood, but by one drop at a time.'”

Before that, I also learned that 'a smart Syrian woman weaves with a donkey’s leg,' which is what I am trying to do now, as I remember the heavy price Egyptians paid for losing their memory, when the National Party building was demolished in 2015, along with many memories demanding change.

'No to demolishing memories'... 'This time for real.'"