This article is part of a dossier in partnership between SyriaUntold and openDemocracy's North Africa, West Asia page, exploring the emerging post-2011 Syrian cinema; its politics, production challenges, censorship, viewership, and where it may be heading next.

Censorship, in all its forms, was among the first challenges faced by Syrian demonstrators in March 2011. These Syrian revolutionaries attempted to break the chains imposed by the regime on their freedom of speech. So it was no surprise then that the camera, as a tool of survival and documentation, was among their first forms of expression. Perhaps it was its vanguard position that permitted it to lead a cinematic “renaissance" that has engaged international festivals throughout the last nine years.

For decades, the National Film Organisation (NFO) weighed down Syrian filmmakers. The NFO was founded so that the regime could monopolise cinematic production, and practise various forms of censorship: whether against film scenarios still on paper, post-production censorship, or even going as far as deciding what does and does not deserve to be screened in cinemas or in Arab and International festivals.

One might say that the history of Syrian cinema is a history of struggling with censorship. Each scenario, each film, encountered a long and difficult journey, from which even the best works and directors were not spared. Media battles were recorded, seals bearing “prohibited from screening” were stamped, directors were even called in for interrogation by the security services. The most infamous of these incidents came when Omar Amiralay was called for interrogation at security branches after his film “A Flood in Ba'ath Country" (Toufan fi Bilad al-Ba’ath) was screened on an Arab TV channel.

After the revolution, Syrian films and cineasts split into two groups. There was cinema produced by the regime, serving mainly as a form of political propaganda of sorts; and there was cinema produced that was against the regime, generally through documentary films (rather than fiction) filmed on the very edge of danger, under siege or shelling. It not only confronted the traditional censorship of the regime, but the camera placed itself exactly in the face of the tank’s canon or the soldier's rifle. This was the case with the now infamous video from Daraa, the so-called "cradle of the revolution" to those very first demonstrations, when a man held up his camera a few steps away from regime soldiers shouting: “Shoot, let the whole world see!”

Propaganda first

One thing worth mentioning, though, is the fact that even the films produced by the NFO benefitted from the expanding margins of freedom of expression made available by the revolution. It seems the regime no longer scrutinises social, religious, sectarian or sexual breaches of censorship norms, as its main concern now is to prove its side of the story. This narrative was adopted to the letter by the films of Joud Said and Najdat Anzour. The regime went further than merely turning a blind eye, to perhaps purposefully committing breaches that support its narrative. For example, it was not previously possible to point to a character's religious, sectarian or ethnic origins. And yet today, you will see a Christian as the hero of a film, as in “Homs Rain" (Matar Homs, 2017) by Joud Said, in harmony with the regime’s claims that it protects religious, sectarian and ethnic minorities.

In fact, one can now find an unbelievable number of censorship “violations" in one film—Mohammad Abdulaziz’s 2013 release, “Four o’Clock Paradise Time” (Arrabi’a bitawqeat Alfirdous). The film presents a Kurdish family, with their traditional attire and names (Kawa-Diersem) as well as, more importantly, their Kurdish language. The familial protagonists speak Kurdish—unprecedented for an officially produced film—which is then translated in to Arabic. It’s common knowledge that that echoes the regime's political shift since the first few weeks of the Syrian uprising, after which the regime flirted with Kurdish elements in society by granting stateless Kurds among them the right to Syrian nationality, a right they'd been denied all of their lives. Overnight, the regime permitted their traditional clothing, songs and names. And yet you cannot find, looking through media coverage and critics' views of this film in regime newspapers, any discussion of this aspect of the film. You barely find a hint at how some of the film’s protagonists are speaking their mother tongue. In regime newspapers, this historic precedent apparently isn't worthy of coverage, celebration, let alone criticism!

The film itself is filled with scenes of intimate kisses, nudity and talk of political opposition parties and former detainees. In some of its scenes, it even mimics one of the forms of Syrian opposition protests, when four young women dressed in white bridal dresses held up banners in the middle of the historic Hamidiyeh market of Damascus. In the film, they hold up a sign saying: “For the sake of Syrian human beings, enough!” When the image juxtaposes the girls and their banners with images of a car bomb explosion, we find that the condemnation of the killing goes in one direction only, and will not refer to random barrel bombs, Scud missiles or live-fire on demonstrators. Either way, in the film, as in reality, the peaceful demonstrators will also be arrested. It's another breach that the cinema would not have allowed before 2011.

But while traditional forms of censorship may have eased up a little, others have appeared. Among those is religious and sectarian censorship—or perhaps that was also an attempt by minorities to benefit from the regime flirting with the alliance of minorities. Najdat Anzour’s latest film "Palm Tree Blood” (Dam Annakheel) found itself caught up in censorship by the Druze sect, simply for having presented a character speaking a Druze accent as a coward. This forced the filmmakers, in perhaps the only precedent in the history of Syrian cinema, to halt commercial screenings, apologise and later remove the scene altogether.

Cinematic commandments

We might say that the new cinema (mainly in documentary form) freed itself completely from regime oppression, and no longer worries about the regime's standards of censorship. However, it is still difficult to deny the emergence of new forms of censorship in certain areas, which had its clear affect in the absence of filmmaking and other art forms. Or perhaps it merely impeded its production cycle.

Within the realms of the NFO, we can speak of creative forms of tricking censorship committees—as Omar Amiralay did with “A Flood in Ba’ath Country” by presenting the NFO with a dummy scenario about ancient ruins in order to shoot a different kind of film. Whereas nowadays, Talal Derki, director of “Of Fathers and Sons" (Aba’a w Abna’a, 2017), also had to make use of trickery—not against censorship committees this time, but against hardline Islamists in rural Idlib. Derki presented himself as a friend of the jihadists, until the moment he was able to finish his film. And we must note here, that among the results of the film screening (along the Oscar nomination) was a wide wave of dismay and criticism for having portrayed Idlib as a hotbed for Islamists, portraying the Syrian revolution as terrorism, while overlooking the regime as the reason behind the catastrophe. Such reactions may be considered an early lesson in the censorship that filmmakers of the new cinema might want to avoid to avert accusations of treachery. More so perhaps because some have created semi-rules or commandments, so that film directors must supposedly relate every theme they address in their films with the regime as the main source of all their disasters.

Perhaps that is what director Firas Fayyad referred to as the remnants of regime censorship in everyone. Fayyad said that: “An entire generation of artists was raised under this censorship and fear. It’s not easy to shed it all off,” adding that, "despite being the revolutionary belonging to the uprising for change and freedom, the artist cannot give away with the residue easily. He will at least bear in mind this or that group that would applaud for and support him.”

He doesn't end there. Fayyad then clarified that acquiescing to funders' agendas—funders who just want to focus on terrorism alone, or condemn one side and not the other—is also problematic. The maker of "Last Men in Aleppo” (Akher Arrijal f Halab, 2017) spoke of how a German jury member objected to his referral to Russia, while he presented a new film project, in saying that “this reveals why the Berlinale avoids any criticism of Russia.” Fayyad is saying that Russia is not only able to influence elections here and wars there, but also cinematic agendas as well.

Fayyad also noted two other forms of censorship follow the release of a film. He spoke of the power of journalism in a country like Turkey, where he lived and worked in recent years, to influence attendance of the audience of a certain film, for example. “Even though Turkey supports the Syrian revolution, they attempt to steer towards a sectarian interpretation of what’s happening,” he said, adding that "newspapers of the political left have considered that my film ‘Last Men in Aleppo’ supports terrorism. This affects you personally as an artist, and may prohibit you from achieving your next film.” Apparently, if you are categorised as such, no one will cooperate with you next time.

Fayyad’s film was repeatedly banned from screening in numerous Arab countries. “In Lebanon they refused to screen it, even though the funding institution, the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC), is based in Lebanon, and screened many other films. Perhaps because those responsible did not delve deeper in to the Syrian situation, but addressed only the themes of Sunni terrorism, refugees and migrant labor.” In Algeria, they clearly said they “cannot screen the film because it will trigger a diplomatic crisis with Syria.” Neither was the film screened in countries like Jordan, Egypt, Morocco or even Qatar, despite the latter having screened less important, but pro-revolution, films beforehand, according to the director. It was not screened in Saudi Arabia either, although the film supposedly does not contradict its political vision or it’s cinematic norms and boundaries.

Cinema director Ammar al-Beik also says that yielding to funders’ agendas is what turned many Syrian projects into reportages rather than films. He wonders: “Is there a TV station that screened films that do not comply with its politics?” Adding that, "there is huge failure in trailing behind global media demands,” whereby, “funders give you money because they expect footage of the war.”

In al-Beik's opinion: “The cinematic film is not merely scenes of sex, politics and religion in the direct sense. Cinema surpasses censorship. It is work on human nature, on mankind, on symbols and philosophical metaphors.”

He does not deny that there are films that were “not possible before 2011.”

“The policeman and sergeant that used to stop you from filming in public for lack of shooting permits, [they] no longer exist." However, he wonders, we do not find a Syrian film that makes the leap in the history of cinema? Why has there not been a film parallel to Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s “Taste of Cherry?"

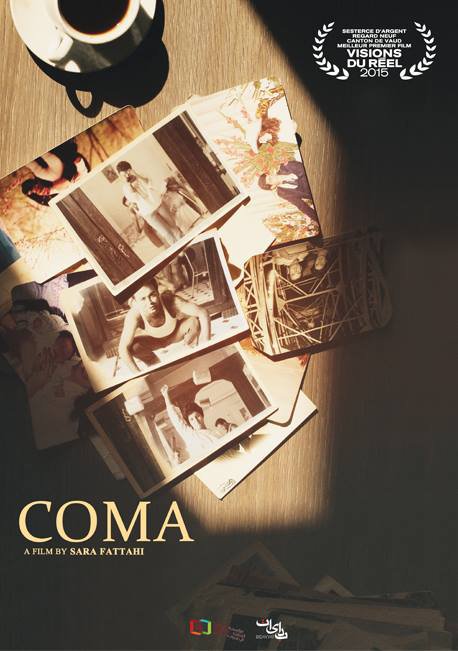

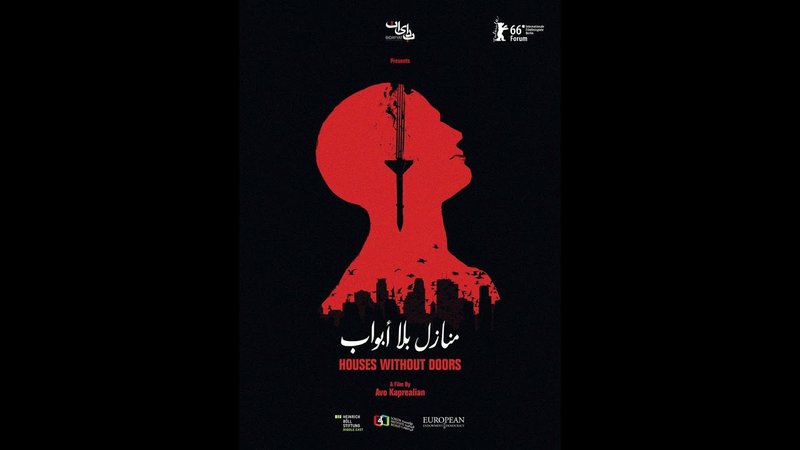

Still, Ammar al-Beik excludes some films, due to their cinematic value, produced by Bidayat about the Syrian revolution, among those “Houses without Doors” (Manazel Bila Abwab) by Avo Kaprealian and “Coma" by Sara Fattahi.

Neutral agendas

If filmmakers’ talk of funding and agendas is considered mere speculation, perhaps we can find a clearer example in the EU’s way of funding short Syrian films. The EU produced 12 short films, aiming to advocate for and empower women in Syria. According to the project coordinator, Malak Swayyed, workshops were held with opposition and loyalist directors and writers before the films were produced. Swayyed said the Europeans set a condition of neutrality in the films, meaning they could not take the side of the regime or the opposition.

And that is how it was. Watching Lath Hajjou’s “The Cord,” which tells the story of a women in labor in an area besieged by a sniper, unable to leave to give birth, we notice the filmmaker’s vigilance not to specify the identity of the sniper. Although the goal declared by the funders is noble and legitimate, it is first and foremost a threat to truth, as well as to cinema itself. For a pro-opposition cineast, the identity of that sniper, or those besieging residential neighbourhoods, is known to everybody. Hiding it is a form of fraud and blurring of truth. If the funder had left it to the directors, each would’ve had his or her way of identifying the sniper.

Despite this firm neutrality, enforced by the EU on those films, which were shot mainly in Lebanon, they did not escape various Lebanese censorships. Swayyed speaks of two incidents, the first occurred during the shooting of a film by director Waha Arraheb in a Syrian refugee camp. A group claiming to be police obstructed them (it was later discovered they were actually Hezbollah), demanding to read the script and were given a dummy script. The second incident relates to director Jamal Salloum’s film “Swing,” which was not even granted a permit by Lebanese security, and was filmed informally instead.

Syrian cinema has more or less escaped regime censorship, or else we would not have witnessed new films and directors reaching the highest ranks in festivals. Perhaps the stumbling of some of them into newly emerging censorships results form the difficulty of changes in Syria overall. The manner with which filmmakers confront all that is what will determine the future of Syrian cinema.