This article was published with support from The Guardian Foundation and International Media Support (IMS). Read part one of this investigation here. A version of this piece was first published in Arabic.

Iron plates are assembled in the shape of a human-sized box; a coffin. A steering wheel like that of a ship pulls the plates closer together. Guards place the prisoner inside the coffin, and they gradually tighten the plates over his chest.

Because of the pressure on my chest from the iron plates during the days I spent in the coffin, I felt numb, and I couldn't hear anything but the laughter of guards while they steered the wheel of the coffin and pressed the plates in the morning each day. All I could think about was the darkness, and pressure inside the coffin. I was living the stories I had heard, and there was no difference, except that I was still alive. -Said*, a former Free Syrian Army-aligned fighter in Idlib

The so-called iron coffin torture technique remains the harshest in the memories of former detainees at al-Oqab Prison, a notorious facility partially built into a cave in rebel-held northwestern Syria, and run by the hardline Islamist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). The group controls most of Idlib governorate in northwestern Syria, one of the last major pockets of opposition control.

According to former detainees, prison guards would use the method to force victims to confess to any number of crimes, or to punish them for violating prison rules.

For young Idlib doctors who treated war wounds, COVID an invisible new threat

02 October 2020

Said, a 29-year-old from northwestern Syria, once fought with the Syrian Revolutionaries Front, an alliance of Free Syrian Army-aligned militias. For his membership in the alliance, he was imprisoned in Oqab in 2014, when the facility was run by HTS predecessor al-Nusra Front.

He says he spent 17 consecutive days inside the iron coffin, and believes the punishment was due to allegations from a prison guard that he was planning to escape Oqab.

His and other testimonies come as the usually secretive HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Jolani appears in recent months in a number of publicity photos—a possible attempt at improving the group’s extremist image.

But gruesome stories gathered from former Oqab prisoners paint a picture of massive human rights abuse by the group.

Fresh air

In one part of the prison’s cave, guards built high walls, forming a room no larger than 30 square meters. Iron bars covered what would have been the ceiling.

The space, former prisoners remember, was used as a breathing room, for fresh air away from the dark and damp prison cells, which had precious little ventilation. Prisoners called the room the tashmisa, or the “sunny corner.”

But, entering the tashmisa depended on strict prison rules, as well as each prisoner’s case and cell location. Nobody in Oqab received their fair share of this space.

Prison management dedicated one day a week to taking prisoners out of their collective cells to the breathing space, and half a day to prisoners in four-person cells, according to former detainees. Those in solitary cells were reportedly only given half a day in the tashmisa, once per month.

Some detainees were allowed even less.

The name “tashmisa” does not correctly describe what it is. Despite the opening in the ceiling, all this corner does is let a little bit of air in, at best. In some instances, perhaps for a few minutes a week, the sun rays might reach it. Besides, it is subject to the same management rules as other cells. Prisoners are not allowed to talk to each other here either, and fear of the inevitable fate that a prisoner might face if he violates these rules prevails, even if it’s just to return his fellow inmate’s greeting. -Abu Hassan*, 47, a former detainee

The room was also where some detainees would receive “lessons” from HTS-aligned religious preachers assigned to the prison.

“We all knew the purpose behind the shariah lessons,” Abu Hassan, a former prisoner, tells SyriaUntold. “We noticed the mind distortion games, the divisive talk, the extreme ideology.”

“But it was our only chance to breathe some fresh air, away from the stench and the humidity in the cave. The air we breathed during the shariah lessons, though sporadic and short-lived, was our only reminder that we were alive.”

‘Nusayriyyah cell’

Yasser al-Salim, a prominent lawyer and rights activist from southern Idlib, spent 126 nights in a solitary cell and 17 nights in a quadruple cell in Oqab, he remembers. Then, he was moved to so-called “Nusayriyyah cell,” named by some prisoners after a derogatory term for members of Bashar al-Assad’s Alawite religious sect.

“The cell included around 40 prisoners, most of whom were Alawite officers in the Syrian Armed Forces, along with an Iranian colonel,” Salim remembers.

Salim had been detained in September 2018 after attending a demonstration in his hometown of Kafranbel. There, he raised banners in solidarity with dozens of Druze women and girls who had been kidnapped several months earlier during a bloody Islamic State attack on Syria’s southern Sweida governorate.

Just hours later, gunmen raided his home and hauled him away.

Hundreds of Syrians participated in solidarity campaigns and demonstrations condemning Salim’s arrest. HTS finally released him on March 1, 2019.

But Salim was not free, despite being outside "the cave," as some former prisoners call Oqab. Nowhere felt safe in Idlib. Salim decided to leave Syria, eventually finding himself in France.

Inside the cave, the torture went on.

I was tied to an iron pole in the middle of the torture chamber, after enduring a “wheel” torture session that lasted for half the night or more. The youngest of the group sat facing me, and he was cursing and crying out insults while sipping his last cup of maté [a drink similar to tea]. As soon as he finished, he threw the leftover hot water on my body. This was one of the hardest moments in that cave, despite the long nights of torture. -Samer, a former detainee

Samer descended more than two dozen steps before finding himself underground. He noticed what appeared to be a torture chamber, in a section of Oqab prison dedicated to detainees who had been members of Syrian opposition factions.

Samer himself had previously fought in an opposition faction, facing bullet wounds to his chest and leg during battles in Idlib in 2016. He was arrested and brought to Oqab later that same year, he says, on charges of “mocking religion and provoking jihadists in Syria.”

Once underground, Samer met an unusual punishment.

Children, the oldest seemingly around 17 years old, were tasked with torturing him for several hours each night. The torture lasted for a week. The children were made to shout insults at him, pour hot water over his body and use other methods of physical abuse.

Other former prisoners also told SyriaUntold they also experienced similar punishment, at the hands of children apparently recruited by prison guards.

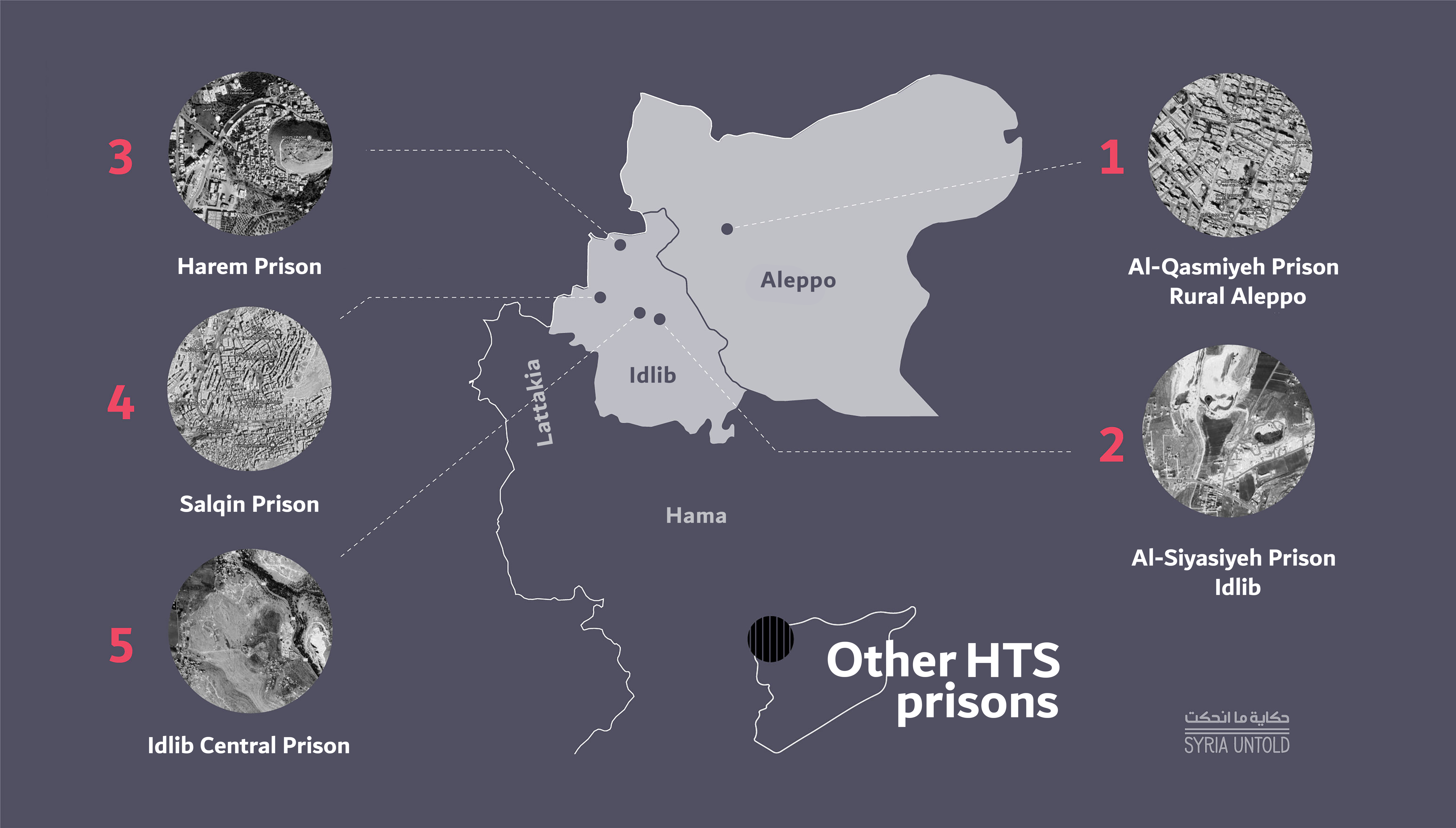

And the misery extended beyond Oqab, former detainees held by HTS remember, as the hardline group ran a network of prisons and detention centers outside that damp cave in rural Idlib.

Beyond Oqab

It felt like something right out of a Hollywood car chase. An HTS vehicle suddenly cut off Abu Ali’s bicycle while he was riding to work near Hanano square in central Idlib city last year.

As soon as he hit the car and fell to the ground, four HTS members covered his eyes with a cloth and put him in the truck of their vehicle, Abu Ali says.

His captors transported him to the Criminal Security Department in Idlib’s city center, where they punched him and shouted insults. He stayed in a cell there for one night, then appeared before a judge.

Up until that point, 27-year-old Abu Ali hadn’t been told of his charge. Then, the judge spoke.

The court of first instance accused me of blocking the path of a patrol during its pursuit of wanted people. When I told the judge about what had happened and showed him the bruises from the beating and my torn clothes, he said, verbatim: “Shut up! This is not proof that they beat you!” I was then sent to Idlib Central Prison on these charges, then to another prison near Darat Ezzat city in Aleppo’s western countryside. I was released on the 14th day. -Abu Ali, a former detainee

Idlib’s Central Prison is located on the northern outskirts of the city. It was under the control of the Syrian government before opposition factions seized it at the end of January 2013.

Al-Nusra, the Islamist group that preceded HTS, raided the facility at the end of 2017 and took control, turning it into its own detention center.

The HTS-run governing authority in Idlib, the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), was later responsible for managing it, and then announced on Dec. 4, 2019 that the prison was out of service. The facility was evacuated.

In February 2020, the prison became a makeshift shelter for hundreds of displaced families, amid massive regime and Russian aerial bombardment on Idlib.

The formal charge that Abu Ali finally found on his release form from Idlib Central Prison: “insulting the emir of the organization.”

HTS, and, previously, al-Nusra, have arrested more than 2,000 people since 2012, according to a 2019 report by the Syrian Network for Human Rights. Those arrested included 23 children and 59 women. Most of the detained have since gone missing, the report said.

The same report documented at least 24 people were killed by torture, including one child, as well as 38 people who were field-executed in HTS prisons and whose bodies were not returned to their families.

Those who have survived the torture nevertheless still suffer.

Hamza, a volunteer rescue worker with the Syria Civil Defence, also known as the White Helmets, spent months in Oqab in 2019 after he published a Facebook post criticizing HTS.

He faced painful torture: electric shocks, and beatings with wooden sticks

“The signs of torture on my body might disappear in a few years,” Hamza says.

“But they will forever remain in my memory. The nightmare of prison has never left me. I can still hear the cries and shouts and the voice of that judge who insulted my mother, as she drowned in tears while begging him to release me.”

*SyriaUntold has changed the names of former detainees quoted in this report to protect their safety.

This report was edited in Arabic by Hassan Arfa and supervised by Mohammad Dibo.