Utrecht and Geneva—Throughout the Middle East, dozens of refugee and internally displaced person (IDP) camps and informal settlements have been set up for the millions of people fleeing from violent conflict. Often, these camps are created in makeshift conditions, with limited resources and under tight time and financial constraints. The environmental footprint of these camps can have serious consequences for local natural resources such as water, or create challenges around waste management.

The United Nations (UN) agencies and other humanitarian organizations involved have years of experience and a wealth of knowledge on this front. Most of the time they manage to set up properly functioning camps that, although not ideal, can meet the basic needs of the target population. But at what cost to the environment and what are the direct and longer-term consequences for both those living in these camps and host communities?

Since the escalation of the Syrian uprising to a full-out armed conflict in 2011, over 6.6 million peoples have been displaced within the country. Another 5.6 million have fled to Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and beyond. In total, 13.1 million Syrians are in need of help, according to UN figures. The majority of the displaced are housed in urban areas, yet a significant number is hosted in camps and informal settlements, with large well-known refugee camps such as the Zaatari and Azraq camps in Jordan. In Iraq, 2.6 million people are still displaced, and Yemen notes a similar number, with 2.2 million IDPs.

Camps and settlements are often no short-term solution. The estimated average lifetime of a refugee camp is 18 years, according to a 2015 Chatham House study. As times passes and with increase of camp-based populations in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, there will be an abundance of challenges. Geographic, meteorological and environmental dynamics will increasingly impact the logistical capacity of aids group and the overall health of camp populations. Syria is already a source of multiple poignant examples. This article will look at emerging environmental health issues in the MENA region that have become a significant challenge for refugee and IDP camps, and related environmental health risks. We will explore some key problems and innovative solutions to address these problems and discuss what opportunities they can provide for building back better and greener in post-conflict reconstruction planning.

Lost between the waste

Environmental conditions in camps or informal settlements can have severe health challenges for its inhabitants due to risks of communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, or exposure to indoor pollution. The environmental footprint of these camps can also severely affect groundwater and soil conditions, create waste management problems, and use up local natural resources, such as wood. These are all issues that are currently being tackled by the many humanitarian actors hard at work on the field.

These issues also bring with them political sensitivities as host communities may object to the socio-economic and environmental consequences of sharing natural resources. This has certainly been the case in dry Jordan, where water demand surpassed supply even before the Syrian crisis. Meanwhile, in Lebanon, waste management has been one of several environmental issues raised in relation to the Syrian refugee presence.

So what lessons can we learn from Middle East conflicts when it comes to managing the environmental health risks of displaced populations and mitigating their impact on the environments? What can be done to improve humanitarian response and reduce its environmental footprint in such areas?

Selecting sites

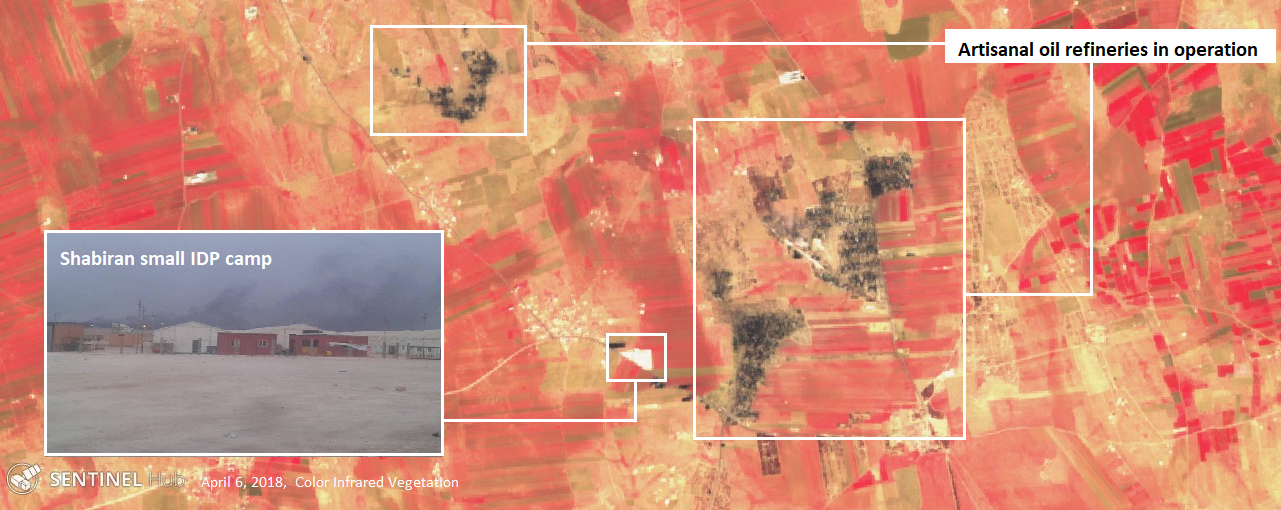

Deciding the locations for camps or informal settlements often proves to be crucial. Recent incidents underscored that the identification of potential pollution sources deserves more scrutiny when finding a suitable location. In August, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) sent out an alarming report of children playing between the toxic waste of artisanal oil refineries in the Arisha camp of Hasakkeh. These makeshift refineries have popped up by the tens of thousand throughout Syria and Iraq, where workers, often children, are laboring in hazardous conditions, inhaling noxious fumes and being exposed to the toxic by-products of crude oil refining.

Recent satellite imagery shows this camp has been growing since August 2017. Using remote sensing we can see the sheer size of some of the camps and visualize how they have been growing over the years. This type of mapping has been done extensively by UNOSAT on Syrian IDP and refugee camps.

A more recent example from May 31 2018 was found on social media. Reports came in from a small camp in the Aleppo countryside that noted how children were suffering from respiratory problems, allegedly from toxic smoke generated by the nearby large-scale artisanal oil refineries.

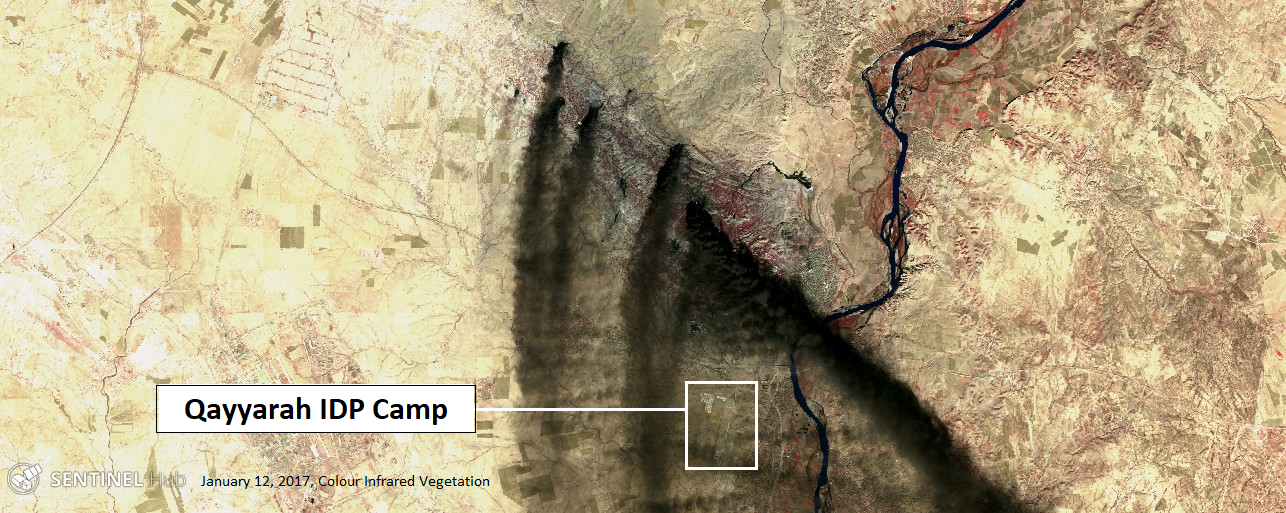

These incidents are stark reminders of how locations of settlement are of importance, although finding a proper location can also be a luxury. The set-up of the IDP camp near Qayyarah in Iraq demonstrated how security constraints limits the choice of locations, as nearby oil well fires caused by the so-called Islamic State escalated, the fumes could reach the camp, and create additional health risks.

Camp settlements can also directly affect natural resources such as woodlands and water. Deforestation is a real issue, causing potential landslides, soil erosion and flooding, loss of habitat, and exacerbating climate change effects, as noted in other humanitarian crises. An estimated 64,700 acres of are burned each year by forcibly displaced families living in camps. In Syria, collecting firewood for energy sources has been a particular issue in Idlib and Hassakeh, as well in besieged areas. An estimated 90% of displaced people lack access to energy, resulting in a multitude of problems. Even local armed groups issued statements in 2017 against cutting down trees, after deforestation started taking its toll on Idlib’s landscape.

The lack of clean cooking solutions and provision of food without fuel in camp settings exposes mostly women and children to sexual and gender based violence due to long hours spent fetching firewood in unprotected areas. Severe health effects result from indoor air pollution while cooking over open fires for hours on end, with an estimated 4 million people dying per year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Kerosene use in densely populated situations increase risk of fire. Potential tensions with host communities and unintended black markets over fuel sources are common when displaced people forced to depend on natural resources to meet energy demand. In other cases, besieged populations have made fuel from burning plastics, as we saw in Ghouta.

Waste generated by the camps can create additional burdens and could affect local groundwater sources as in Lebanon and Jordan. Massive influxes of displaced people into areas unequipped with infrastructure to handle waste can contribute to the spreading of diseases. In areas of extreme intense seasonal climate variation, the displaced or besieged resort to practices such as burning trash to keep warm. Additionally, as camps turn into protracted settlements, their infrastructure is largely based on fossil fuel backed generators, contributing to diesel supply chains and thus war economies as well as emitting green house gases. In situations of unreliable diesel supply, off-grid hospitals and humanitarian doctors suffer severely without the tools to treat wounded or deliver children.

Despite a clear need for intervention, the environment falls behind.

Due to the vast and sheer amount of need during emergency response and the simple lack of funding to meet needs, environment and energy are not top priorities. The current estimates are that hundreds of millions of US dollars are spent on diesel and generators. Therefore, humanitarian agencies lack the capacity to coordinate and plan holistically in a manner that mitigates environmental damage. Additionally, the notion that camps and settlements for displaced people will last for short periods of time commonly prohibits any long-term planning, despite the potential to become protracted crisis situations. The fragile nature of displacement situations, short term funding cycles and host countries without the capacity to equitably respond and mitigate these detrimental environmental effects are further barriers that prevent systemic change on the topic.

Solutions and appetite to change

Despite the political, structural, financial and capacity barriers faced to holistically implement better environmental practices, interventions are possible through advances in the clean energy access space, increased political and economic feasibility, pay as you go financing models and disruptive innovation in RE solutions. Donors and humanitarians enabled the Za’atari and Azraq camps of Jordan have been poster child examples of how to work with host governments and meet priorities while providing job opportunities that benefit displaced people. Often in cases where the electricity grid is not expanded to refugee settlements or is too unreliable to invest in grid connected solar systems, stand-alone systems with storage can be used to provide power to critical needs of displaced people, such as in the case of the Mam Rashan refugee camp in Northern Iraq.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is implementing a solar water, sanitation and hygiene program (WASH), equipping displaced people with the technical skills to maintain infrastructure. The Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves is a public private partnerships that is creating a thriving market of efficient and clean cookstoves, and is working with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNCHR) on cultural based intervention to accelerate clean cooking solutions. Small scale solution such as the Gravity Light, off-grid refrigerator Coolar and the ACE 1 can be easily provided via distribution or ideally on the local market place for positive effects. Other initiatives are exploring options of using waste for various recyclicing purposes to limited the environmental footprint.

The political ground is fertile. The Global Compact for Refugees and Migrants is an ongoing political process to create an overall shift in the management of displaced populations and mitigate negative environmental impact. It envisions fitting the 'camp' approach into a more 'whole of society' approach where investments into solar and other renewable sources will provide a framework for integrated displaced people and host communities. Clean energy solutions can thus be a key tool for peacebuilding and development in fragile situations when working with local governments to meet their development targets and mitigate tensions over natural resources from the start of large scale involuntary displacement.

Ultimately, the evidence for change and investment case will need to be strong to mobilize resources and address the socio-economic complexities and wide scale variance of energy demand in refugee settings. Solar systems with large upfront cost pose a risky investment in fragile conflict or post-conflict zones, an investment that has not been realized at scale to date. Research into the economic viability and quantifying the case for investment—such as recent work from the Moving Energy Initiative and researchers at Oxford and ETH Zurich—are vital for understanding how to link solutions to refugee settlements.

As the case for investment grows stronger, funding mechanisms such as the Green Climate Fund, Global Environmental Facility and renewable energy credits can be leveraged by aid agencies and private sector companies for larger scale impact. Realizing the massive environmental impact caused by large scale forced displacement, the World Bank has released $2 billion until 2020 in grants and low risk loans to meet demands of hosting governments. The human and environmental benefits of renewables are clear. Flexible and portable Photovoltaic (PV) systems for humanitarian settings exist. De-risking and unlocking the economic case will be pivotal for long term sustainability.

Sunshine or gasoline

While displaced populations were struggling to find better solutions to energy, and at the same time, awareness among humanitarian organisations, host states and local authorities on environmental issues increased, this both lead to a notable change towards sustainable alternatives in particular clean energy with solar power. Some of these changes can be seen with open-source tools, such as the IKEA and German government funded solar farms near the the Zaatari and Azraq refugee camps. In Syria, doctors struggling with work due to frequent power disruptions decided to invest in solar energy panels at hospitals in northern Syria, while initiatives in Daara in the south also start to bear fruits. Other experts have put forward proposals [PDF] to push for more solar energy in reconstruction projects.

In Yemen, the humanitarian blockade and energy crises caused by the ongoing bloody conflict due to damage to oil pipelines and power plants. This lead to a significant increase of solar energy and growing initiatives to promote solar energy [PDF] to become more energy independent. This boost in solar energy production managed also reach areas that previous had no access to electricity. A 2017 World Bank report estimates that there is a $1 billion market for solar energy in Yemen in the coming five years. In Lebanon, home to over a million refugees, solar energy also received a 112 % increase in 2015 alone, with ongoing tenders to develop larger scale solar farms. However, some remain sceptical for the utility of solar power in post-conflict reconstruction in the Middle East, noting the abundance of crude oil and the vast financial interests of States and commercial parties in exploiting this market instead of shifting to renewables.

Building back better and greener

This article set out to see how the conflict in the MENA region impact the environmental health and wellbeing of displaced populations living in camps and settlement resulting from polluting practices, hazardous living conditions and lack of alternatives. The article further outlined what the environmental consequences are for the host communities and ecology as deforestation, waste dumping and scarce water sources lead to soil and groundwater degradation. From burning plastic to setting up camps near hazardous hotspots, displaced populations face many security and health challenges stacked up their already miserable situation. We have outlined how a variety of these challenges also resulted in a boost novel, energy sustainable approaches. Lack of unsustainable energy sources such as fuel and wood spurred many actors in the Middle East, be it governmental, humanitarian or local communities, to look for alternatives that makes them independent from polluting and unsustainable energy resources.

These developments should provide sufficient food for thought on both what the wider environmental dimension of conflicts are for displaced people and their host communities, and what we can learn about responding to these events in way that provides a roadmap for building back conflict-affected states with better, greener and more sustainable. In a region rife with issues related to water shortage, conflict-pollution, desertification and a weak environmental governance system, innovative solutions and local green initiatives are key to providing a hopeful prospect to the future. In the context of the Syrian conflict with no near end in sight, there is a huge opportunity to support hosting countries with legacy sustainable energy and reap ample positive environmental benefits - albeit with its own set of political, financial and technical challenges.

These concerns have also been flagged in forums such as the UN Environmental Assembly (UNEA), where resolution 2.15 on protection of the environment in armed conflict particular addressed issues around displacement and environmental degradation caused by conflict, while the 2017 UNEA resolution 3.1 on highlighted the potential impact of conflict pollution on displaced populations. Both resolutions were unanimously adopted by States. Now it is time for States to live up to their commitments and work on the implementation of these resolutions. Ultimately, unlocking clean energy supply and sustainable responses from the start of displacement are conduits for helping the millions of displaced Syrians rebuild their war-torn lives while simultaneously preserving the state of their temporary homes.