There is no doubt that the Arab uprisings stand out, among other things, as media phenomena. This articulation is seen through two fundamental dimensions: coverage of the uprisings by regional and international media, and the successful utilisation of the information revolution in developing 'alternative' media projects in the region. The alternative media served, primarily, as an source of information: subverting authoritarian censorship regimes and delivering the news into the public sphere. However, it also served as an organiser and mobiliser in calling for protests and spreading propaganda messages against these totalitarian regimes.

The role of these social networks as an incubator for activists, providing spaces beyond the control of the authorities, is a common feature both in the Syrian uprising and in others across the Arab world. However, the impact of these social networks in Syria was different to those of other uprisings in the region, and continued to take different forms as the Syrian movement developed. Let us now look more closely at the role played by social networks in the Arab uprisings in general, and in the Syrian one in particular.

Virtual/real debate

The tremendous technological development in the information technology sector and spread of new internet realities integrated people into a virtual 'society'. Perhaps the most obvious outcome of this are the “social networks” where millions of people participate according to their interests. Active participation in these networks has even pushed some sociologists to speak of them as a “world”, “public sphere” or “virtual reality”. Howard Rheingold, in his 1994 book, went so far as to describe these nascent entities as “virtual communities”.

Building on these ideas, and the noticeable increase in the number of participants in Arab social networks, many Arab and western experts exaggerated the impact of these networks and their role in the Arab uprisings. The underlying reasons for the eruptions on the streets had little to do with the availability and development of information and communication technology, nor were later developments dependent on them.

Arab societies during the uprisings concentrated their protest efforts in small representative communities in public spaces like Tahrir Square in Cairo, Sittin Square in Sanaa and Habib Bourguiba Street in Tunis. The role of social networks was to deliver news, call for protests, and to contribute in the diffusion of political symbols and values from these micro communities to the larger public sphere.

Syria, however, was an exception to this process. The absence of large protest spaces--due to systematic repression by Syria's security and military apparatus--as well as the concentration of protests in the periphery and the relative lack of action from the large urban centers (Damascus and Aleppo) established social networks as the only space outside the control of the Syrian authorities, and thus the only space where Syrians could interact freely.

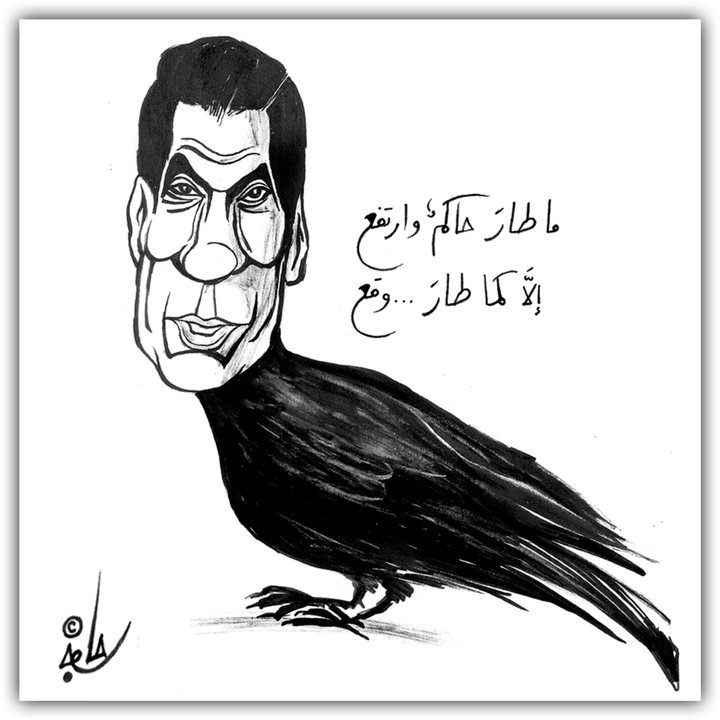

Syrian president Bashar al-Assad described these protests in his 30 March 2011 speech to the parliament as a “virtual wave” or “fashion” that had broekn out in social networks, and at the service of foreign agendas aiming to undermine the political system. It was clear that Assad’s denial of the existence of the protests was compatible with the convenient assumption that the Arab uprisings were nothing more than the products of imagined virtual worlds. Thus, in the authoritarian understanding of the term “reality” becomes that which is clear in its manifestation and in the authority’s ability to control it. In contrast, the virtual is only an “illusion”, because it is outside the regime’s control. Consequently, any oppositional movement that is able to communicate freely, to question, problematize, and redefine the authority’s preferred reality is dismissed as “virtual”.

Who wins?

In the early days of the uprising (and to a lesser extent today) Facebook was the most popular site for Syrian interaction. Several online activists attempted to copy some of the strategies of the Egyptian revolution. Facebook pages like the Syrian Revolution, or Syrian Day of Rage, were established and called for mass protests on certain days, but these calls went largely unnoticed. It became obvious that the traditional avenues of mobilisation, like publicising videos of regime human rights violations, were not enough to evoke the latent public resentment and turn it towards protest. Yet, these efforts energised activists on the ground, and several graffiti campaigns were launched in Syrian cities. The tragedy of children of Daraa was a direct result of graffiti: finally, the security response that followed it became the 'catalyst' for the protest movement and its diffusion into other cities.

It can be said that the virtual component of the uprising was limited in its impact, focusing on relaying the events and explaining them. The “Syrian Revolution Against Bashar al-Assad 2011” Facebook page, the largest such virtual aggregation of people opposing the regime, was not able to privilege its own political discourse in the early stages. “Downfall of the regime” as a political slogan, was only adopted publicly in May 2011 after the regime started using the military against the growing protests, despite the page tirelessly pushing for its adoption as early as mid January 2011.

Thus, it was the military escalation by the regime that helped privilege the virtual channels in determining the shape and content of the uprising’s political discourse. Faced by the massive repressive force used by the regime, grassroots activists and the protest movement on the ground were unable to shape a coherent civil disobedience movement with specific demands and symbols. This task fell on the virtual congregations which took the lead in determining the collective political values and symbols for the disparate movement; contributing to the emergence of several new currents in public opinion that were not present in the early stages of the uprising.

French psychologist, Gustave Le Bon, used to speculate in his book on crowd psychology that “disparate individuals could attain the character of a psychological crowd at a certain moment under the influence of violent emotions or a great national event.” In Syria, we could posit that the virtual interactions between disparate individuals did indeed produce a psychological crowd under the influence of a great national event, i.e. the uprising. Since the “Syrian Revolution” Facebook page was the largest such virtual body, and with the absence of real public spaces for the uprising, it was the interactions within it that largely determined many of the directions and the symbols of the uprising.

The names given to the Friday protests was a major channel for shaping public opinion in Syria, in which the social networks played a significant role. The “Syrian Revolution” page, by introducing weekly voting mechanisms became the de-facto leader of the Friday naming process. While the page was successful in privileging many of the names preferred by it, discussions on the issues significantly reflected large and even fundamental differences over the future of the country. The controversies about Friday names like “Friday of the Descendants of Khalid”, “Friday of International Protection”, or “Friday of the Syrian National Council” were representative of larger schisms and differences within the uprising. No example of this is more poignant than that of the debate on adopting a different flag to represent the uprising: Syria’s green independence flag, rather than the current red one. Such was the influence of the uprising’s virtual component in that period that a new national symbol was adopted as early as November 2011 as the de-facto flag of the revolution.

The influence of virtual communities increased over the course of the early uprising. However, as the uprising’s militant side grew and gained support, the balance of power shifted again, to favour actors, of a rather different sort, on the ground.

Translated by: Yazan Badran