The embattled Syrian president Bashar al-Asad is irreplaceable. No other Syrian political and military key figure in the regime’s echelons could substitute the president at the visible top of the pyramid. The system remains standing thanks to the very presence of Hafez al-Asad’s heir on the façade of the structure of power and his dismissal would mean the fall of the regime. His role is also considered crucial by its local, regional and international allies.

Despite the numerous publications and studies that have appeared in recent years on aspects of the Syrian issue, scholars and experts have devoted little attention so far to the root causes of the regime’s stability and its apparent internal cohesion. The main question is how the regime’s inner circle has managed to partially preserve its power amidst unprecedented events and how it has been able to re-adjust its structure and posture during the last five years.

Answering this question will allow us to understand that future institutions will remain a tool in the regime's grid of powers as long as Bashar al-Asad remains in control of the system. The overall structure of this grid of powers and the related decades-old social contract have almost remained immune to legal reforms throughout the uprising to avoid the collapse of the regime. This means that the permanence of Asad is paramount to the survival of the entrenched network of powers.

The Grid of Powers in Asad's Syria

The fact that Asad jr. is not replaceable could be seen as a lack of flexibility of the regime, which could be thus considered ready to collapse, as it has not mastered the necessary skills to generate alternatives to Bashar al-Asad. In early 2011, the system was certainly shaken by large-scale popular demonstrations. Nevertheless, it has shown a high level of resilience in the long run.

More than five years after the first protests and the subsequent governmental repression, the Syrian regime and its allies firmly control the vital Daraa-Damascus-Homs-Hama axis and the coastal region. Thanks to the crucial Russian aerial support, it has also regained ground in Palmyra region, which is rich of natural resources such as natural gas and phosphates. Damascus city, the physical and symbolic core of the Syrian power, is nowadays more protected than before from external threats.

In 2011, the regime's only viable option was to resort to the military as it felt that there was no room for political alternatives. For the Asads and their allies a real reform of the system would have meant a deep revision of the decades-old social contract, causing an unacceptable loss of power and the regime’s collapse.

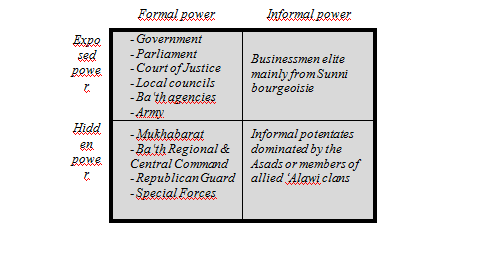

Since decades, in Asad's Syria power has been structured along two lines, exposed (A) and hidden (B) levels of power, and divided into two columns, formal (1) and informal (2) power. Observers can read dynamics of Syrian power through this four-cells grid: exposed-formal (A1), hidden-formal (B1); exposed-informal (A2); hidden-informal (B2).

![[Table 1: Formal Vs Informal Power – Exposed Vs Hidden Power. This and the following table have been originally elaborated in Trombetta, Lorenzo, "Beyond the Party: the shifting structure of Syria’s power", in Anceschi Luca, Gervasio Gennaro & Teti Andrea (eds.), Hidden Geographies: Informal Powers in the Greater Middle East, (London: Routledge, 2014)].](http://www.syriauntold.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/1st-table.png)

In the upper-right cell (A2, exposed-informal power) there are those businessmen who are well connected to the top-echelons of the regime's inner circle. In the lower-right cell (B2, hidden-informal) there are the most influential members of the regime, as they have direct access to the military and security apparatus and exert control over the main financial and commercial policies of the regime.

In this context and for a long time, dissidents have been calling for political and judicial reforms in Syria. On top of these demands there was the abolishment of Decree n.51, widely known as the Emergency Law, dating back to 1962, and Article n.8 of the 1973 Constitution, which effectively guaranteed the Baath party unchallenged dominance inside and outside the parliament.

Decree n.51 entered into force in December 1962, right after the end of the United Arab Republic and few weeks before the Baʻthist "revolution" (1963). For almost half a century this decree has regulated the relationship between citizens, judicial bodies and law enforcement agencies, explicitly connecting the exposed with the hidden levels of formal power (A1-B1). This law severely limited individual freedoms, granting authorities the power to prohibit public gatherings and issue travel bans, as well as to hold anyone "suspected of undermining public security" in police custody indefinitely.

At that time, new crimes were codified in the Penal Code such as "attempting to form a secret society", "inciting sectarian and racial hatred”, “attempting to alter the nature of the state”, “disseminating false information to weaken the morale of society”, “interaction with hostile foreign entities”. These types of crimes were tried by military courts.

The repression of the 1964 Hama popular uprising was the first successful test for Decree n.51, which has since proved to be an exceptional instrument of control and repression of dissent.

The Emergency Law was abrogated in 2011, when president Asad aimed to show its will to meet popular demands for reform. However, the relationship between citizens and judicial authorities remained unchanged, because Decree n.51 was replaced by Decree n.55, also known as “Anti-Terrorism Law”. The new decree officially gives security services the power to hold a person in custody up to 60 days, but this limit is practically ignored by security agencies. The Anti-Terrorism Law confirms also the jurisdiction of military courts over civil trials.

Moreover, when Asad ordered the abolition of the Emergency Law, he did not order the retraction of Decree n.69, which had entered into force in September 2008. This decree amended the Penal Code so that any agent of the security services accused of abuse or torture would be put on trial only via the approval of the head of the armed forces. Decree 69 is still valid and grants full immunity to all members of the control and repression agencies. It is deeply tied to the hidden-formal cell (B1) of the aforementioned grid.

In such a long-standing intimidating and violent environment, it has been difficult for citizens to cast their vote. The situation is identical today, even though the Baʻth is no longer "the leading party in the society and the state" - as it was stated in Article n. 8 of the 1973 Constitution. In 2012 a new Constitution was approved, and Article n.8 does not contain anymore any reference to the supremacy of the Baath party over other political formations. But the Baath continues to play a key national and local role at the exposed-formal level (A1) of power. In fact, the party still dominates the National Progressive Front, the platform created in 1972 by Assad sr. and composed by the "neutralized" wings of the communist, socialist and Nasserite parties, which have been the main political rivals of the Baath since the mid-60s.

According to the new Electoral Law (2014), the Baath retains de facto the majority of seats in the Parliament. Both in 2012 and 2016, the majority of the elected deputies in the legislative elections belonged to the category “workers and peasants”, which is traditionally appointed by the Baath party local and central committees. In fact, the new Electoral Law still divides the “people” into two main categories: on one side workers and peasants, on the other, everyone else. The law states that "the percentage of the representatives of the first category should account for at least 50% of all seats in the Assembly" (Article n. 22).

![[Photo: The Syrian flags hanging on a polling booth during the 2014 presidential elections - Damascus - 3-6-2014 (Hosein Zohrevand/source: http://goo.gl/9JafgA/CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Creative Commons)].](http://www.syriauntold.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/A_polling_booth_of_2014_Syrian_presidential_election_in_Damascus_4.jpg)

The "Asadization" of Power

Deeply aware of the need to preserve the power structure, Bashar al-Asad and his allies have chosen in 2011 the only viable path that could lead them to the political and physical survival: police and military repression.

Yet, this attitude broke away from Hafez al-Asad’s legacy. During Asad sr. rule, repression was indeed a crucial factor in maintaining stability, but it was diluted in a more articulated system of alliances that went beyond sectarian and family allegiances.

The power pyramid modeled by Hafez al-Asad was based on both family solidarity and a broad political consensus. These elements allowed him to reduce tensions and protect his regime for almost three decades. In a nutshell, Asad sr. succeeded in striking an overall balance between the four cells of the above mentioned power grid.

![[Photo: Hafez al-Asad's first inauguration as President in the People's Council, March 1971. L–R: Asad, Abdullah al-Ahmar, Prime Minister Abdul Rahman Khleifawi, Assistant Regional Secretary Mohamad Jaber Bajbouj, Foreign Minister Abdul Halim Khaddam and People's Council Speaker Fihmi al-Yusufi. In the third civilian row are Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass (MP in the 1971 Parliament) and Air Force Commander Naji Jamil. Behind Tlass is Rifaat al-Assad, Assad's younger brother. On the far right in the fourth row is future vice president Zuhair Masharqa, and behind Abdullah al-Ahmar is Deputy Prime Minister Mohammad Haidar - Damascus (Syrian History Archive/Public Domain via Wikimedia Creative Commons)].](http://www.syriauntold.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The_first_innaugaration_of_President_Hafez_al-Assad_in_Parliament_-_March_1971-1200x768.jpg)

The analysis of the changes occurred inside the structure of the regime in the first decade of Asad jr.'s rule reveals a gradual process of "Asadization" of power. Between 2001 and 2010, members of the Asad family and representatives of those few clans closely linked to the Asads by blood ties – the Makhlufs and the Shalishs above all - seized control of most of the power centers at the highest levels of the pyramid1. In a nutshell, the informal-hidden power (B2) has taken over the other sectors of the structure.

The regime has thus lost some key supporting pillars – top figures in the Baʿth party in peripheral contexts, some key commanders in the regular army, influential Aleppian and Damascene businessmen - that were representative of the various components of the Baʿthist society as it was shaped under Hafez al-Asad.

When the first popular protests took the streets in spring 2011, the regime was thus weaker than before. Its "Asadization" had strengthened the belief among Asad jr. and his allies that the crackdown was the only way to survive.

To achieve this goal, the ruling élite has so far managed to weather the crisis taking advantage of some elements of continuity with the pre-2011 period as well as introducing new crucial power features.

On the one hand, the Asads had to give up part of their sovereignty in the decision-making process in favor of their Russian and Iranian allies. In particular, top Syrian commanders officially continue to head the four main security agencies, but their rule is now more limited than in the past as they are de facto under the influence of their foreign colleagues.

Similarly, in the name of the so-called coordination against terrorism, Syrian élite corps and loyalist militias (such as the National Defense Forces) passed under the de facto jurisdiction of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, the Lebanese Hezbollah militia and the Russian military command2.

![[Photo: Bashar al-Asad with Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev - Syria - 10-5-2010 (Kremlin.ru/CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)].](http://www.syriauntold.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Dmitry_Medvedev_in_Syria_10_May_2010-5.jpeg)

In continuity with the past, the regime uses the institutional façade of formal powers – the exposed (A1) and the hidden ones (B1) - to operate politically, militarily, economically at an informal level. Here, the Asads and their close allies constitute the core of the oligarchy whose cohesion is based mainly on family and community ties.

The "Asadized" Syrian regime, significantly supported by its foreign allies, has succeeded so far in resisting internal and external pressures. This result has been also achieved thanks to a blatant lack of coordination between political and armed Syrian opponents and their Western, Turkish and Arab Gulf sponsors.

No Alternative to Asad

What seems even more relevant to future developments is that there is no alternative to Bashar al-Asad at the top of the Syrian pyramid; he continues to be the only public figure able to represent the various Syrian powers, exposed and hidden ones, formal and informal ones.

The issue of replacing Asad jr. should not be approached according to the outcome of the process of identification of the successor, but from the inception of this process. When in early 1994 Basil al-Asad, the eldest son of president Hafez al-Asad, died in an obscure road accident, the second son Bashar was not ready to be appointed as the future successor to the president. It took six long years to “build” Bashar al-Asad as the new head of the Syrian Arab Republic through a process that followed different military and political tracks, including the moulding of a new public figure.

The new president simultaneously had to embody continuity (being part of the military structure) and discontinuity (a young, reformer president). These two traits merged into the figure of a political leader able to speak to internal stakeholders (communities, entrepreneurs, religious figures, local and central institutions) and external ones (allies and regional and international rivals). In 1994, Hafez al-Asad knew that his power was coming to an end, but his physical disappearance did not mean the demise of the regime.

Until now, Bashar al-Asad and his allies have not started the process of grooming a successor to the president and foreign attempts to identify an alternative to Bashar have failed before starting. For instance, former foreign minister and vice president Faruq ash-Sharaʻ has been seen by many as a potential interlocutor of both warring parties in the post-Asad phase. However, Sharaʻ has long been excluded from the inner mechanisms of formal, informal, hidden and visible powers. He has no family connections with the Asads and has no more base of support in the Syrian business and political sectors.

In the last two years, some confidential sources named army Colonel Suhayl al-Hasan as a potential successor to Asad jr. Also known as ‘the Tiger’, since 2013 colonel Hasan has been publicly praised for his military achievements in central and northern Syria. Posters with his picture have appeared on numerous Syrian streets and online amateur videos show him in military fatigues as he motivates troops.

Colonel Hasan belongs to an Alawite clan of the coastal region of Jabla, but he is not tied directly to the Asads nor to the Makhlufs. He could rely on a significant base of support in the armed forces but he is not trustworthy in the eyes of the Asads and the inner circle

Neither vice-president Sharaʻ nor Colonel Hasan could be seriously considered as successors to Bashar al-Asad. From a clannish point of view, this person should emerge from the circles of the informal-hidden power; at the same time, he should be recognized as a leader by the national institutions (formal-visible), by the security apparatus (formal-hidden) and by the entrepreneurial and financial sectors (informal-visible). This figure does not currently exist.

Today more than yesterday, Asad jr. represents the "patriotic" Syrian façade of a power that has lost part of its Syrian identity. This loss should not be visible, for revealing this shift of power and identity would mean revealing a contradiction of which everyone is aware while nobody wants to admit it.

Bibliography:

1- Aoyama, Hiroyuki (2001), "History Does Not Repeat Itself (Or Does It?!): The Political Changes in Syria after Hafiz al-Asad’s Death", in Middle East Studies Series, Ide-Jetro, 50, pp. 13-20.

2- Bahouth, Joseph, Les entrepreneurs syriens: économie, affaires et politique, (Cermoc: Beirut, 1994).

3- Batatu, Hanna, Syria’s Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables and their Politics,(Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1999).

4- Boukhayma, Sakina (2000), "Chronique d’une succession" , in Maghreb-Machrek, 169, pp. 164-72.

5- Burgat, François – Paoli, Bruno (a cura di), Pas de printemps pour la Syrie . Les clès pour comprendre les acteurs et les défis de la crise (2011-2013) , (Editions La Découverte: Paris, 2013).

6- Chouet, Alain (1995), "L’espace tribale des alaouites à l’èpreuve du pouvoir. La disintegration par la politique", in Maghreb-Machrek, 147, pp. 93-119.

7- Haddad, Bassam, Business Networks in Syria. The Political Economy of Authoritarian Resilience, (Standford University Press, Standford: California, 2012).

8- Haidar, Dalia – Fares Muhammad, "A family Affair", in Syria Today, February 2010. Available at http://goo.gl/i3ovY.

9- Hindi (al-), Ahed, "The Kingdom of Silence and Humiliation", in Foreign Policy, October 16, 2012. Available at http://goo.gl/J9CsA.

10- Hinnebusch, Raymond, Syria: Revolution from Above, (Routledge: London, 2002).

11- Perthes, Volker, "Syria: Difficult Inheritance", in Perthes, Volker (ed.), Arab Elites: Negotiating the Politics of Change, (Lynne Rienner: Boulder-London, 2004), pp. 87-111.

12- Sayed, Hani, "Fear of arrest", in Jadaliyya, August 6, 2011. Available at http://goo.gl/9lN6M.

13- Schmidt, Soren, "The State and the Political Economy of Reform in Syria" , St Andrews Paper on Contemporary Syria, (University of St Andrews, Centre for Syrian Studies: St Andrews, Scotland, 2009).

14- Trombetta, Lorenzo, "Beyond the Party: Patterns of Elite Runover in Syria between- the two al-Asads", in Anceschi, Luca – Gervasio, Gennaro – Teti, Andrea (eds.), Informal Power in the Greater Middle East, (Routledge: London, 2013).

15- Van Dam, Nikolaos, The Struggle for Power in Syria. Politics and Society under Asad and the Baath Party, (I.B. Tauris: London, 1979-2011).

[1st Photo: Typical propaganda poster featuring Syrian president Bashar al-Asad. The poster reads "We are all with you" - ʿAmarah al-Juwaniyyah - Damascus - 25-9-2007 (watchsmart/CC BY 2.0)].