A ‘Pyrrhic Victory’

That is what the UN’s special envoy to Syria Staffan de Mistura called the Syrian regime offensive in East Aleppo in an interview published on November 15, 2016. At a time when we are lost for words, those were well-chosen words.

A victory achieved at too high a cost it will certainly be: all humanitarian standards and accepted conducts of war have been transgressed in this offensive, and in the war in general. The regime may win ground and improve their strategic position, but they have tainted themselves in the eyes of Syrians and in the eyes of the world. Their allies have tainted themselves badly too, as have all parties who have committed war crimes in Syria.

Can these criminal actions ever be the basis for ruling Syria? On one level it may happen. But only if by ‘rule’ we mean suppress and dominate in a constant violation of the popular will backed by draconian security.

The notion of a pyrrhic victory is a good starting point for thinking about peace-making in a situation where the evidence of war crimes is clear and considerable. The question that everyone will have to reckon with in peace-making Syria is what to do with the evidence. Of course the answer to that question will largely depend on the conditions under which peace-making takes place, the military positions won and the diplomatic game on the international stage.

But whatever the conditions -- a full victory for the regime, or local control of territories as a basis for renegotiating the political order in Syria -- it is unthinkable that peace-making can ignore the archived evidence. What will happen to this material, and what kind of political work must take place to organize it and prepare legal processes? This question is likely to become a crucial one once the war is over, and even while it is going on.

No One Can Say: “We Didn’t Know”

Because Syria is now one of the most documented conflicts in history, and a scattered archive of the war is under construction. Hundreds of thousands of videos, testimonies, and images exist on the internet, much of it documenting transgression of international humanitarian law. The incriminated parties are primarily the Syrian regime, but also count opposition and rebel groups, regional armies and mercenaries, and Russia and the US.

To date, hardly any research has been done to collect, compare and converge the material gathered by the many Syrian and international organizations, commissions and groups that since 2011 have recorded and catalogued war crimes, including torture, forced disappearances, bombardment of the civilian population with conventional and non-conventional weapons, massacres and wanton killing. Their aim is to ensure that an archive of human rights abuses exists which may produce some form of justice in the future.

Syrian activists and artists, and forums like SyriaUntold, have also created a substantive body of evidence and reflection on the war, which could potentially complement legal evidence in a transitional justice process aimed at retribution, healing, or both. As a whole, violence documentation in Syria constitutes an emerging and ‘hybrid’ archive in the sense that it consists of many types of material motivated by multiple ideological and political interests.

These acts of archiving represent a range of emotional and legalistic visions of transitional justice. Whereas Syrians and others documenting violence on the ground often seek to provoke an emotional response in the audience, legalistic advocacy seeks to “stay the hand of vengeance”1 through non-emotional bureaucratic language and long-term juridical processes instituting global norms. Both approaches overlap in their insistence on creating archives for the war.

The Internet Abounds with Evidence

Atrocities filmed with mobile phones, YouTube videos, blogs, webpages and the intense media coverage of the fighting in Syria provide a raw material that organizations can mine for evidence, even if the evidence would mostly be too flimsy for it to hold up in court.

Therefore, organizations such as the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) collect more oral and written evidence of the chain of command from top officials in the regime to special police forces and soldiers who executed and tortured protesters and opposition fighters.

These documents, smuggled out of Syria and now in multiple locations in Europe and the West, can be supplemented by violence documentation such as the Caesar files, a collection of 53,000 photos smuggled out by a regime defector, and in the end a legal case can potentially be made, either at the International Criminal Court or against individual regime members residing in Western countries. The photos show abuse and murder of prisoners by the Syrian regime.

Other material, ranging from meticulous reports of every bombing and murder to forensic evidence gathering, is being put together by a complex landscape of Syrian activists, foreign states, international and national non-government organizations, as well as international institutions such as United Nations agencies. Different political interests and forces seek to remember, restore, and archive the war in Syria.

The Syrian actors include among others the Kawakibi Center for Documenting Violations, Center for Documentation of Violations in Syria, Centre for Civil Society and Democracy, Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies, Dawlaty, Local Coordination Committees in Syria, Syrian Center for Documentation, Syria Justice & Accountability Centre (SJAC), Syrian Observatory for Human Rights and Syrian Shuhada.

International organizations include the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, in addition to international NGOs such as Alkarama, Amnesty International, Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, Medicines Sans Frontiers, United States Institute of Peace, CIJA, Human Rights Watch, International Crisis Group, Justice for Syria, Reporters Without Borders, Syrian Emergency Task Force, and Syrian Human Rights Committee. This list is far from complete. All in all more than 40 documentation groups exist.

Transitional Justice and Its Various Motivations

Syrians tend to have personal reasons for collecting evidence, and many of them have close connections to opposition groups. They want to maintain the momentum of the uprising and hope for justice to be done and for regime members to be tried as part of a transition of power.

Outside actors often frame their intervention in terms of abstract notions of universal justice, preserving a workable international system, maintaining historical progression of humankind, and similar lofty ideals.

For example, the director of CIJA Bill Wiley recently told The New Yorker that his work to retrieve documentation of crimes against humanity was not about removing leaders such as Saddam Hussein and Bashar al-Assad as such, but “about sending a signal to a conflict-affected society that, from here on out, this nation will be governed on the basis of the rule of law.” Of course the two aims are overlapping, which explains the collusion between Syrian and international groups.

The human suffering that continues apace at a staggering level undermines faith in the ability of the international legal and diplomatic community to end the fighting and begin addressing the multiple emergencies in Syria and in the region.

In that sense the situation in Syria constitutes not just a crisis for Syrians, but also for international conflict resolution. It puts into question the ability of the current international system to address the thousands of documented war crimes and crimes against humanity, defined in the ICC Rome Statute as acts “committed as part of a widespread systematic attack against any civilian population”2.

The “dilemmas of protection”3 have not been resolved by existing measures such as the Responsibility to Protect doctrine and the UN Security Council.

Many actors in the conflict, from the local level of peaceful activists alienated by the militarization of their struggle, to international actors with no real belief in the diplomatic or military effort to stop the war, have instead turned to the collection of evidence as an attempt to establish a just international system. The archive they create has become an alternative location for ambitions of restoring global morality, as well as for keeping alive the original revolutionary project in Syria.

Transitional Justice Is No Miracle Cure

In fact, the paradigm has been heavily critisiced in recent years, and there are reasons to be skeptical. When it comes to Syria, I do understand the reservations some may have about focusing on transitional justice when bombs are falling in Aleppo.

Some would even argue that the focus on social and political relations in a future post-conflict setting could impede the necessary work to bring these relations about in the present. Transitional justice can become a distraction from the realities of war, a pie in the sky when the sky is filled with MIGs.

There is another way to formulate the critique. If we look at the failed peace-making attempts of the last five years, the international community and Western diplomats have never offered a vision that was both realistic and acceptable to all parties. Perhaps this was due to a basic miscalculation of the strength and tenacity of the Syrian regime and its allies Hezbollah, Iran and Russia. When the U.S., the UN envoys and key allies of the armed groups fighting the regime have talked about Syria as they imagine it after the war, they consistently assumed the defeat of the Asad regime or, at a minimum, the departure of Asad.

By weaving the thread of defeat – and a transitional phase on the road to a new political order - into their diplomatic narrative, they hoped it would become the accepted, expected outcome. The apparent failure of this teleology has gradually, since the summer of 2013, meant that diplomatic scenarios jarred with reality and could not become a platform for the coveted ‘political solution’.

This Is Not a Pro-Regime Argument

In fact, I have heard it most bitterly made by members of the peaceful uprising. Looking through my field notes from summer 2013, I find a recording of a conversation with a Syrian friend who had recently arrived in Beirut.

This was shortly after the regime and Hezbollah won the battle of Qusayr, cutting supply lines between Lebanon and Homs. The Islamic State group [back then known as Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant] had appeared on the scene as an important player, and an air of defeat hang over the Syrian revolutionary community in Beirut.

From my friend’s point of view, and from the point of view of many likeminded secular protestors, the tide had turned decisively on their revolution. Not only had their peaceful protests become militarized, while they were being brutalized by the regime. What was worse, the turn to armed struggle had transformed their struggle into an intractable, endless muddle of regional and international powers slugging it out by proxy.

A protracted civil war, in which the other revolutionaries -- Islamist in coloring -- were stronger and better connected, and therefore better equipped to drive the struggle against the Asad regime forward. In this disconsolate perspective, which has only become gloomier over the last three years, he hardly saw any point of talking about the revolution. War had replaced it, and that war looked like defeat.

I suggested that what needed to be done, at least, was to document the atrocities committed against civilians in the hope that justice would be done after the war. I mentioned the Violence Documentation Centre, headed by Razan Zaitouneh, as a model for revolutionary work in this protracted conflict, and as an example of the necessary work to assemble an archive of human rights abuses and, eventually, achieve transitional justice.

That remark triggered him off. “Transitional justice! This is for people who don’t want to get their hands dirty. You can dream about transitional government like Kofi Annan [the UN Special Envoy to Syria 2011-12] but this is not what we need. This isn’t what we needed, I mean. Like transitional government is already there and they are all sitting down together. It’s not!

“And he [Bashar al-Asad] is laughing, you know. We don’t need these sugarcoated words, he [Asad] will take them with his coffee, yaʻtik al-afiye [and say thank you very much]. No way. You know? We lost, it was because of these lies.”

Perhaps He Had a Point

The inability of the international community to back talks of transition with diplomatic and military pressure has made a mockery of liberal political visions. When diplomat-speak provides no tangible results for the work to keep the revolution and its central ambition of a new political culture alive, it is easy to become despondent. About justice in particular.

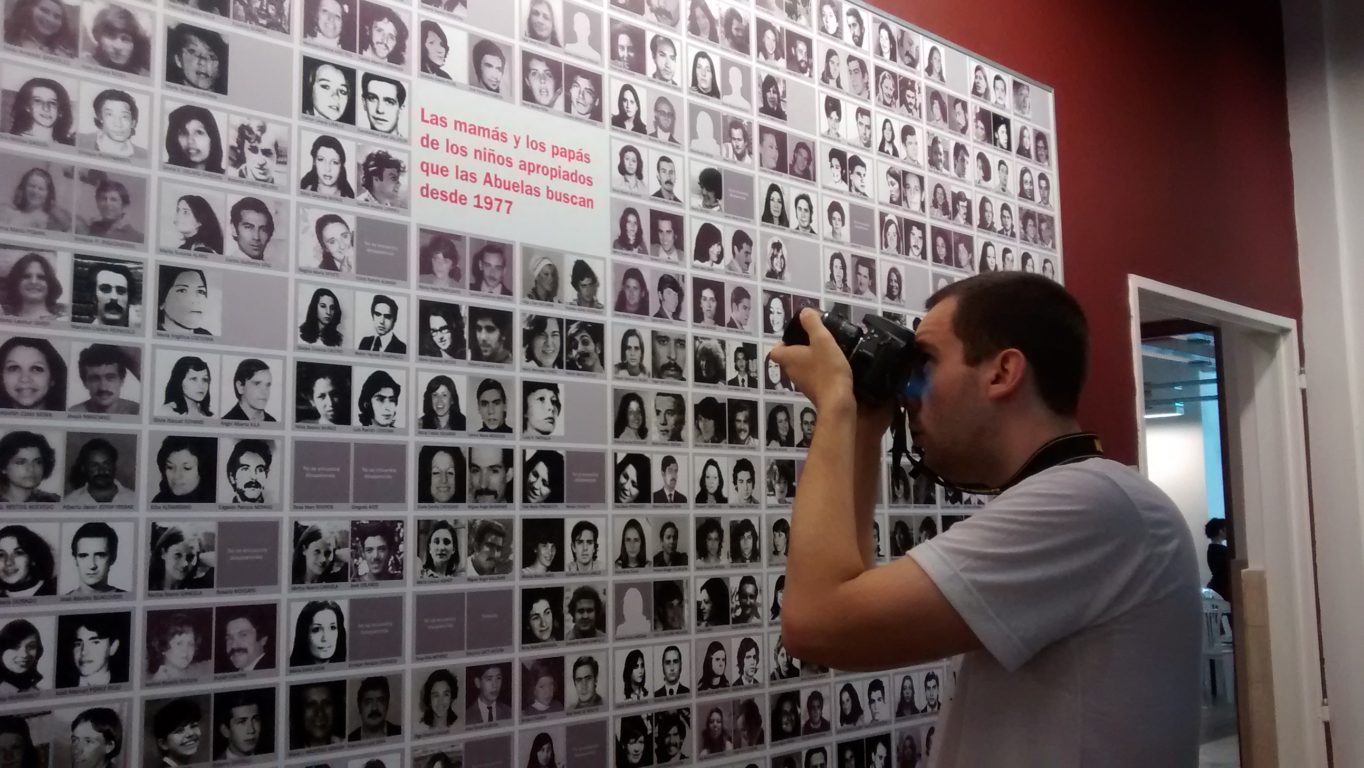

At the same time, we need to remember that there have been other cases in recent history -- such as Chile and Argentina -- where conflicts had to be resolved by ignoring justice partially or fully, initially, only to come back on the agenda later. This is when archives become crucial.

Seen in a larger perspective, any political peace agreement is only ever a starting point for an equally difficult transitional process of societal reconstruction and reconciliation, in which the past looms large. It is never possible to fully neglect the past. Even when a regime tries to bury them, past violations tend to return at some point.

How Could Peace-Making in Syria Begin?

The prospect of President Trump taking office in January has left the regime’s main armed opponents in a dire situation. Even if Trump’s policies remain to be seen, they appear to move American support further away from the Free Syrian Army, and completely away from most Islamist-oriented movements, and to favor strong cooperation with Russia.

If the current Aleppo offensive continues at its current gruesome velocity, chances are that opposition control of East Aleppo will be finished before Trump takes office, setting the scene for new conditions for peace talks.

Under such circumstances, it is hard to imagine that the UN could return to the terms stipulated in the Geneva I or II conferences of 2013 and 2014. That could provide a backs-against-the wall situation in which negotiation will be the only other option than total defeat. Nonetheless, the regime may even push for a complete victory in Idlib and the remaining rebel-held territories.

In order to avoid absolute defeat, opposition forces are likely to demand power-sharing. This, again, would follow a pattern we have seen in other transitions from war. Many peace negotiations have focused on ending violence by giving power-sharing incentives to warring parties. Lebanon is a near case in point, or, more recently, Colombia.

So far, however, the regime has tried to foreclose this opportunity by closing down dialogue over the legitimacy of all opposition groups – by calling them terrorist and denying their popular base.

This has led to a “radical disagreement”. According to one of the world’s leading peace researchers, Oliver Ramsbotham, a “radical disagreement” is when parties refuse to distinguish positions from interest and needs, and therefore object to reframe competition into shared problem-solving which could reshape adversarial debate into constructive controversy4. In short, when there is no capacity for mutual understanding, a future political settlement seems impossible.

For the sake of Syria’s future, we must hope that a settlement will come. If it does, it must also include crimes committed by regional powers, by Western countries, and indeed all involved. But pointing to violations by the U.S. and other Western armies will only amplify the infinitely larger evidence of regime violence. The regime cannot erase the war. It destroyed Hama in 1982, and managed to erase the evidence and close down discussion. But we are living in different times.

The archive of the Syrian war is there, and its workers are many and committed, even if the hard work to connect its many bodies of evidence is still to be done. That work is urgent so that the ground is prepared for reckoning with the past in peace-making Syria.

[Main image: Animated film describes how post-conflict justice could develop in Syria - 9-10-2013 (Institute for War & Peace Reporting/Fair use. All rights reserved to the author)].