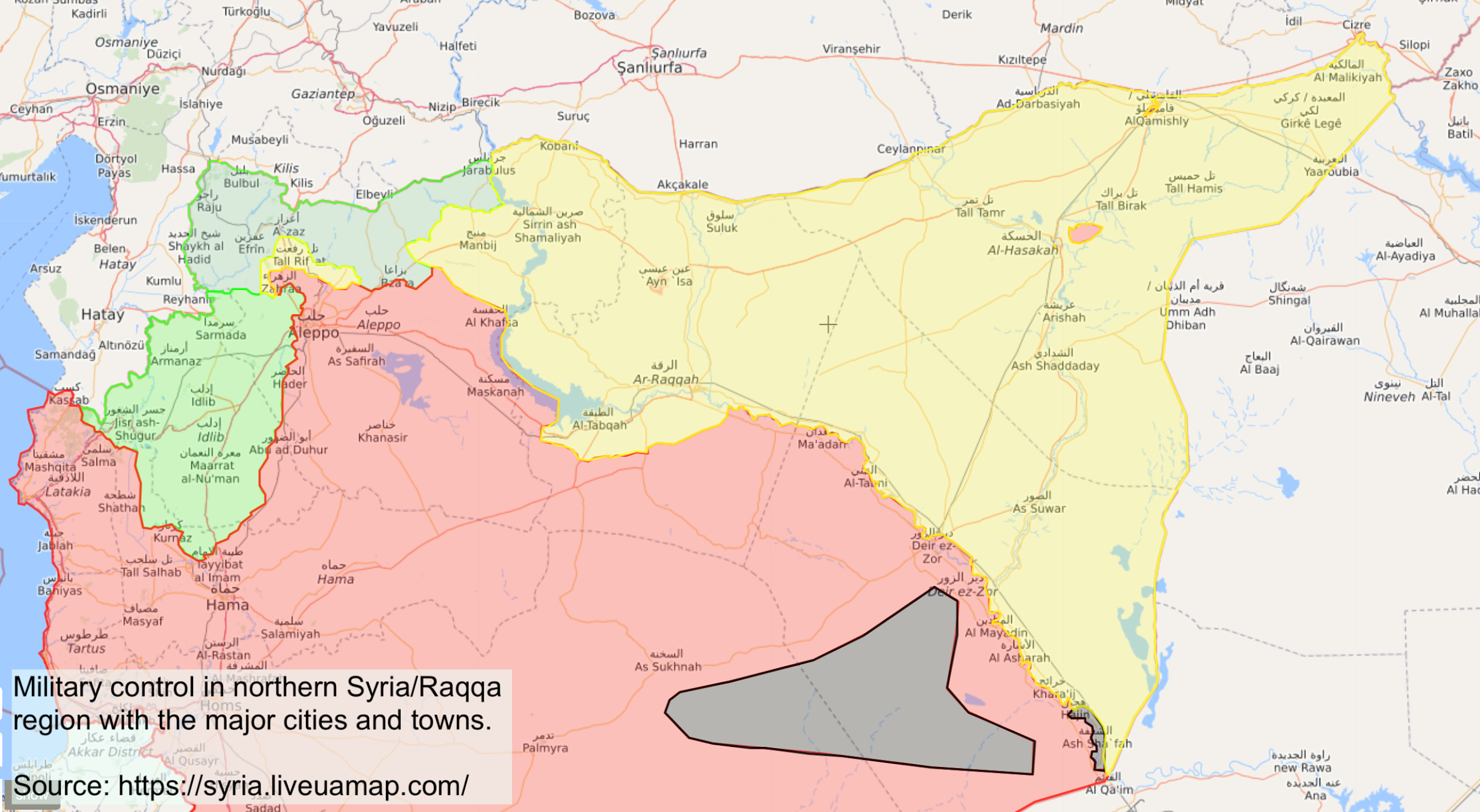

In this last article, we will explore the journalistic field in Raqqa and its surroundings as it developed since mid-2017 when the so-called Islamic State (IS) was pushed out of the city.

The region of Raqqa has a distinct history in the Syrian context. After the regime forces left, in March 2013, the city was occupied by Jihadist groups led by Jabhat al-Nusra. According to one media activist, “the regime withdrew from Raqqa like the Israelis withdrew from Gaza – they wanted a bad example”.[1] A struggle for dominance between al-Nusra and IS took place during that year, with the latter taking full control in January 2014. The city thence became its capital.

These years were characterized by the imposition of Islamic law by IS, and the repression of any sign of dissent. Raqqa was also the main spot where IS propaganda’s videos were shot. Nevertheless, some networks of media activists like Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently operated secretly in order to show to the world what life was like under IS rule. Ten members of the group paid for their activism with their lives, being hunted by IS in Syria and Turkey.

On 6 June 2017, the city was captured after a long campaign by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) under the leadership of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and with aerial and material support from the US-led International Coalition. The “liberation” came at a very high price. A large part of the city’s buildings and infrastructure were destroyed by aerial bombardment and thousands of civilians lost their lives. Today, the region is slowly recovering and going through a process of reconstruction, with basic services not yet fully re-established.

Immediately after IS was driven out, many people started to come back. The Raqqa Civil Council (RCC) was established in April 2017 to administrate the city. It is composed mostly of Arab members, but also Kurds, Turkmen, and other ethnic groups populating the region. Some of the journalists we interviewed claim that the RCC is primarily under the control of the US-led Coalition. Others see it as the long arm of the PYD aiming to expand its influence in Raqqa.

At the same time, the RCC does not have a clear structure and territorial mandate. Other local councils, as the Tabaqa Council, have been established directly by the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), the political organ of the SDF. Moreover, the RCC suffers from a lack of funding, as its direct funders, and in particular the US, are reluctant to finance a complete reconstruction process until the future of the region, and of Syria, are settled in a more comprehensive way. This also negatively influences the legitimacy and the credibility of the RCC.

In September 2018, the SDC created the General Council, which is tasked with the coordination between Kurdish-majority regions and Arab-majority regions. It includes representatives from the councils of al-Jazeera, Kobani, Manbij, Raqqa, and Tabaqa. According to Farid Ati, co-chair of the General Council, “civil administrations have been formed in the areas that were freed from the Islamic State. Temporary civil administrations were formed by virtue of laws that vary from one region to another. The General Council will allow for unifying these laws and legislations”.

An unstable context

This is the context in which some media organizations are beginning to operate again. The media environment in Raqqa, as the one in Rojava, cannot be read through a black and white prism. Media operate in a complex and fluid environment where diverse factors and actors affect their role.

The fact that the region is still in a condition of war, with IS cells active in the territory, deeply influences how journalists can move and operate, as well as the margins of their freedom of expression.

Journalism in Rojava (I): Media Institutions, Regulations and Organisations

29 March 2019

Political actors currently in power in the region emphasize two elements: “reconstruction” and “stability”. Reconstruction does not only mean infrastructures, services and buildings. It encompasses the cultural heritage left by years of rule by Jabhat al-Nusra and IS and what they see as a fractured identity and social fabric. Stability means to restore security while the war on IS winds down, and to deal with the bubbling ethnic and social tensions. In particular, the fear of falling under the control of the SDF remains at the base of constant tensions in the city. Moreover, the slow pace of reconstruction and provisions of basic services also constitutes a major element of dissatisfaction.

The media system in Raqqa presents many similarities with that of Rojava. Because of the SDF’s role, the media institutions of Rojava are present here too, and in general, the organization of the media field seems to respond to the same logic. The media outlets in Raqqa today play a role that is strongly constrained by the current conditions. Many journalists we talked to acknowledge the relevance of the social responsibility they bear in this phase, and act accordingly. Even if they didn’t, then as is the case in Rojava, the political actors can easily force them to change their behavior. At the same time, some space for criticism exists, and some media outlets try to use that, and give voice to dissent when they see the possibility.

The fragile security situation makes media work subject to the usual limitations imposed in war theatres

The fragile security situation has inescapable implications on the work of journalists in the region. As one moves away from the main cities security decreases considerably, and thus the movement of reporters is sometimes limited and their coverage is subject to the usual limitations imposed in war theatres. At the time of writing this, it was still strictly forbidden to use a mobile phone to take photos in public, even by licensed journalists.

The lack of services is another factor for the slow development of media. Even in the city of Raqqa, electricity is available for only ten hours per day, strongly limiting the use of televisions and computers. Telecommunications, through the regime-controlled mobile networks of Syriatel and MTN, were restored only in November. The Internet is dependent on mobile coverage and a cable network that is extended from Iraqi Kurdistan through Rojava.

Mapping the media environment

The media system is not yet clearly regulated, and its operation is often quite chaotic. In theory, the Raqqa Civil Council (RCC), along with the SDF media office, is entitled to grant licenses to media outlets and reporters. However, journalists soon discovered they needed other licenses to operate outside of Raqqa. For example, in Ayn Issa, a few kilometers away, the license is granted by a media office in Tell Abyad, and in Shaddadi by a media office in Qamishli. Al-Tabqa, on the other hand, has its own civil council.

In terms of media actors, we find a media environment dominated by a new generation of media outlets supported mainly by the US state department, the British foreign office, and the US army. Some of these outlets operate mostly as Facebook platforms such as Raqqa between two bridges and Raqqa is our family. More relevant, also because of the lack of electricity, are the FM radios: Mari FM, Amal FM, Bissan FM, Shufi Mafi, and Sawt al-Raqqa. They were all established after the SDF forces expelled IS with the support of the US.

Some other outlets that offer extensive coverage of the region but cannot be considered local media organizations are also present. Such is the case of Jorf News, created when IS was still ruling Raqqa, and ASO Network. Both these organizations have their main staff out of the country and rely on a network of reporters on the ground. Moreover, they say they are not funded directly by the US or its allies.

Finally, there are some media platforms directly controlled by the autonomous administration, such as al-Tabqa FM and Sawt al-Deir. Moreover, Hawar News Agency, the official news agency of Rojava, is also active in Raqqa, as well as the PYD official television Ronahi TV.

According to Ahmad al-Hussein, from the media office of the SDF, there are two main official organizations tasked with oversight over the media in Raqqa. The Media center of the SDF releases news about the region, including Deir Ez-zor, and they grant licenses to journalists crossing into the region, together with Rojava’s Union of Free Media (UFM) and Higher Council for Media (HCM).[2]

The RCC media center is also responsible for licensing journalists who want to cover issues related to the council but also to the city in general and the civil life there.

According to al-Hussein, there is a significant coordination in the work of these official organs, alongside Rojava state media, Ronahi and Hawar, to ensure a consistent message. And there are discussions to unify the regulatory and licensing operations of media outlets and journalists in one organ that combines the SDF media office and the RCC media office.

Media of reconstruction

In the context of Raqqa, it seems that one of the main expectations of both “independent” private media and official ones is to play a role as counter-propaganda against religious extremism. A second major role expected of the media is to cover and encourage the regeneration of the local social fabric, and to give visibility to the reconstruction of local infrastructure.

Journalism in Rojava (II): Independent Media Between Freedom and Control

05 April 2019

We can observe this in, for example, the presentation paper of Sawt al-Raqqa: “Our main mission is to provide reliable and objective news and information on what is happening in the Raqqa region, and on humanitarian assistance and stabilization efforts provided there. It also aims to amplify local people's voices and shed light on their everyday needs and problems, with a particular focus on IDPs and post-conflict problems (social, psychological, security and so on)”.[3]

Amal FM’s mission statement likewise stresses that they aim to “shed light on the practices of ISIS and their human rights violations against our people in Raqqa and the other territories that were under its control”.[4] Mizar Matar, founder of the Facebook platform Raqqa between two bridges, says that they aim primarily at “reminding the people of al-Raqqa of their cultural values and lifestyles before the war started”.[5]

Thus, local journalists appear generally to privilege a social responsibility aspect of their work. They say that, for now, the priority, also among the population, is to go back to a normal life and to find again a common identity.

According to Serdar Mele Darwish, the founder of ASO Network, the situation in Raqqa is generally more open than in Rojava, even if one cannot directly criticize the authorities and the armed forces. At the same time, he adds, this is quite comprehensible given the current situation. Ordinary people themselves have other priorities than political issues: they want to return to a normal life. Giving the people a voice and to denounce the current shortages should be the main objective of local media outlets for the time being. Also, to criticize too much the current administration would mean only to play the game of political actors, like Turkey or IS, who oppose the SDF because of their own interests.[6]

Confronting directly the authorities is seen by many of the journalists we interviewed as irresponsible and unrealistic. A platform like Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently is often criticized because, in the critics’ opinion, they portray SDF almost as negatively as IS. Of course, a more acquiescent approach also enables private media to deal more easily with the SDF and the PYD who dominate the broader political context, and to survive.

Control over the media

The tendency to adopt a “responsible approach” is not simply down to choice. Forms of control exist, and they generally follow dynamics similar to those in Rojava.

Journalists and media outlets have to obtain a license from the RCC which, according to some interviewees, often acts as an extension of the SDF. Media outlets that are considered hostile are not granted licenses, and journalists who cross the red lines can see their licenses revoked. Without a license, access to official sources is limited, as is filming or taking pictures in public spaces. For example, Radio Amal saw their license withdrawn for one month because, they say, they relied on Anadolu News Agency (the official Turkish news agency) as a source for one news piece. When they asked for an explanation by the RCC, they received no answer. The license was finally reissued, after the radio committed to stop using Anadolu.

When necessary, the authorities do not hesitate to contact the media outlets directly. Journalists say that arrests and intimidations are also used as an extreme measure, albeit less frequently.

Some journalists or media activists today have to operate in secret, without a license. This is the case of Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently, given its critical stance against the SDF, but is also the case for many freelance reporters writing for Syrian independent media.

The journalists we interviewed say that there are clear red lines that cannot be crossed when it comes to media coverage. The political status quo cannot be challenged in any way. Moreover, some political positions are not tolerated. It is not possible, for example, to express clear support for the Syrian revolution or for the regime in local media. While foreign actors, including the US or Europe, can be criticized, it is impossible to do so with the PYD and the SDF.

Bashar Yousef, editor in chief of Sawt al-Raqqa, says on this point: “There are limits to what can be covered of course. For example, you can talk about the issues related to the lack of services. And you can criticize the RCC and its local officials, and the consequences of the coalition’s campaign like the victims of the mines. However, all aspects related to security issues are a bright red line. For example, covering assassinations or explosions, when they occur, is considered by the administration to endanger the process of reconstruction and restoring stability. In these cases, we have to wait for the political authorities to produce a statement first before we can report the incident. Also, there are a few specific expressions that they force us to use in the news reports”.[7]

However, the journalists we interviewed also stress that the RCC, which responds to the Americans more than to the SDF, tends to be more collaborative and constructive than the institutions directly related to the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. This makes it easier to cover the city of Raqqa than other areas where the licenses are more dependent on the SDF, and are closer to ongoing war efforts.

Margins of freedom

In this context, local media focus primarily on social and cultural issues, and highlight civil society activities related to the reconstruction. The dominant political narratives are never challenged, and politics in general is not considered as a priority. Moreover, the absence of civil society groups active in domains such as human rights or politics constitutes another limitation for media outlets.[8]

Some journalists express dissatisfaction with the situation, comparing the limitations of freedom of expressions to those existing in other parts of Syria. Others, however, are more positive. Hazem al-Hussein, a freelance journalist, maintains that local media can still play a positive role, if limited. They can show the level of destruction of the area, and give voice to the complaints of the residents. Problems such as lack of services can also be covered relatively easily. This is still tolerated, and even encouraged, in order to place pressure on the international community and unblock funds.

whereas political issues at the general level are considered a taboo, local and social issues can be covered without too many constraints, even when they are critical of local authorities

In other words, whereas political issues at the general level are considered a taboo, local and social issues can be covered without too many constraints, even when they are critical of local authorities. In rare cases, also more controversial issues are also covered. For example, according to Hazem al-Hussein, Jorf News covered the killing of Sheikh Bashir Faisal al-Huwaidi, one of the most important tribal leaders in the region, and the demonstrations that followed.[9]

In this sense, according to some journalists, these outlets can still negotiate a relevant role in giving voice to some critical opinions and civil society organizations, while hoping that in the future the political context will enlarge the space of what can be said at a higher political level.

[1] Quoted in Yassin-Kassab, R. and al-Shami, L. (2016). Burning Country. p. 130. London: Pluto Press.

[2] Ahmad al-Hussein, SDF Press, Skype interview, 15 December 2018

[3] See https://www.facebook.com/pg/sawtraqqa/about/?ref=page_internal.

[4] Amal FM, About us, http://radioamalfm.com/%D9%85%D9%86-%D9%86%D8%AD%D9%86/

[5] Mizar Matar, Raqqa between two bridges, interview, 11 December 2018.

[6] Serdar Mele Darwish, journalist founder of ASO Network, interview, 17 December 2018

[7] Bashar Yousef, editor-in-chief of Sawt al-Raqqa, interview, 18 December 2018.

[8] See for example this mapping study of civil society organisations in Raqqa by the Civil Society Support Center of Raqqa: https://www.raqqacenter.com/report/Raqqa_Civil_Society_Landscape_EN.pdf

[9] Hazem al-Hussein, freelance journalist, interview, 11 December 2018.