A room in the Rukn al-Din neighborhood in the Syrian capital, Damascus. The power is cut, the room is so cold and dark that the faces of the four children who live there became pale. Oum Obaida is 38-year-old, she sat beside her children, preparing food for them, and praying that her stove fire will not die, the gas cylinder is “nearing its end” as she put it.

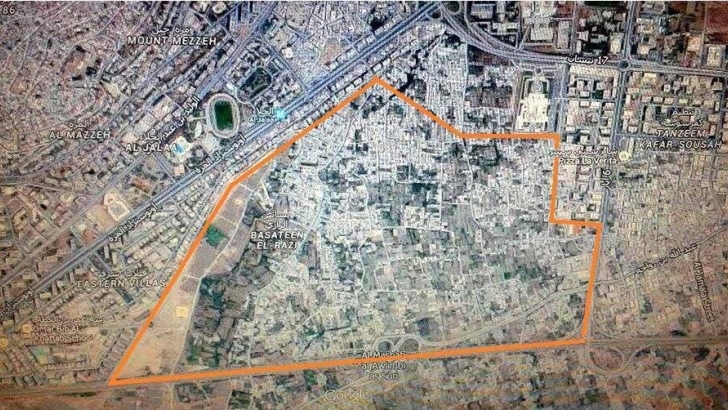

Oum Obaida is originally from Mezzeh neighborhood, and she lived alone with her children since her husband managed to escape to Lebanon. They had lost their home after regime bulldozers leveled al-Ikhlas neighborhood, located in the cactus fields of Mezzeh, known as Mezzeh Basateen, leaving behind nothing but ruins.

She took the phone out of her purse and started showing photos of her old home from which she was forcibly displaced, “This is the living room. And here is the courtyard of the house, and there you can see the mint and vegetable plots.” She sighed as she talked.

“This is the cactus field. Behind every picture, there are a thousand stories, and pain that cannot be put into words,” she continued.

Oum Obaida shook the gas cylinder, nearly depleted before the food had finished simmering. “We left our home in 2014, and the house remained intact for a whole year, though the furniture in it was looted. In June of 2015, the house was demolished, and the bulldozers began leveling it according to the news we received at the time. Now, we have no documents proving our ownership of the house.”

Oum Obaida had contacted several lawyers to prove her ownership of the house, but to no avail. Decree No. 66 of 2012, regulating the reconstruction in the neighborhoods of Mezzeh, Kafar Sousah, Darayya and al-Qadam in Damascus, stipulates that individuals who hire attorneys to prove their ownership must first certify the power of attorney document from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as obtain clearances from the security forces.

In Oum Obaida’s case, no such clearances can be obtained, since her husband is wanted by the regime. In case of failing to acquire a proof of ownership and registering it officially within a certain timeframe, the property would then be sold via public auction, as per Decree No. 66.

The demolition of residential homes was not limited to al-Ikhlas neighborhood, which had witnessed protests against the regime with the start of the revolution in 2011, but extended to the neighborhoods of Kafar Sousah and al-Lawan in central Damascus.

The eviction of people from their homes began after the authorities started implementing Decree No. 66 of 2012 last year. This followed an announcement by Damascus Cham Holding Company, which was formed by the Damascus Governorate Council, of its intention to invest in the areas stretching between east of Mezzeh and the cactus fields, all the way to the Iranian Embassy and Al-Razi Hospital. The project was named Marota City, which, according to the Governorate of Damascus, translates to “sovereignty” or “homeland” from the original Syriac language.

Despite official promises to give financial compensation to the former residents in the areas where the project will be built, no one has been given any such compensation so far.

According to several testimonies by people displaced from the neighborhood, they received a notice to evacuate the area in June of 2015, security agents from Branch 235 of the Military Security were present, as well as the local municipal councillor. The notices were considered legally binding. If the family were not present and signed it, then the notice was posted on their doors.

Shareholders, not owners

Under the aforementioned decree, owners of properties in the concerned areas would receive shares in the planned housing real estate. However, the law is a de facto seizure of people’s properties, as it designates present owners with the status of shareholders in larger areas in the future. This status would deprive them of the right to owning the property they would live in, thus rendering them future tenants of these buildings, not their owners.

Both the Ministry of Public Works and Housing and the Governorate of Damascus co-signed contracts with the current owners. However, these contracts did not specify a timeframe for the completion of the project, and do not include any penalty clauses in case of delay. This gives development companies and investors a large margin to manoeuvre, evade, and renege on their legal commitments.

Law No. 10: Property, Lawfare, and New Social Order in Syria

26 July 2018

Official statements and talk shows discussing the project on national TV promise that this project will be an advanced and successful pioneering example of the reconstruction efforts in Damascus after the war. However, in reality, this project is similar to any other housing development. The only thing that is ‘pioneering’ about it is the large number of houses it demolished and the people it displaced by force. These people today are all scattered in small and inadequate housing elsewhere, with their future uncertain.

Darayya; the error law No. 10 insists on perpetuating

Inside a carpenter workshop in Jaramana, a suburb near Damascus, Walid sat listening to a panel discussion on Syrian television. They were discussing the merits of Law No. 10, which was issued in 2018 and regulates reconstruction efforts in all of Syria. Some analysts considered Law No. 10 an expansion of the mandate of Decree No. 66, which was limited to Damascus. The panel included the Deputy Minister of Public Works and Housing, along with a number of officials. The discussion mainly focused on the advantages offered by Law No. 10, and how it will help achieve advanced architectural developments that will change the face of Damascus, and heal the scars of war.

Walid shook his head, flicked the ash off his cigarette, and resumed his work, and the voice of the presenter faded under the noises of electric saws cutting through wood. The presenter and his guests remained in the background, mouthing and gesticulating, but their voices did not reach Walid’s ears.

Walid is 26-year-old, he was forcibly displaced from Darayya five years ago. He now lives with his family in a carpenter’s workshop in Jaramana, where his children are growing up surrounded by power tools and cans of glue.

“We managed to escape from Darayya after clashes erupted there in 2013, we owned two large woodwork shops, and a multi-story building” Walid said. “After the regime regained control over Darayya in 2016, residents were not allowed to return or enter their town. Later, access to town had conditions; residents have to obtain security permissions from the National Security Bureau. These permissions are never granted to individuals who, themselves or any of their family members, participated in the revolution in 2011. Even if such permissions are obtained, people are never allowed to stay in their homes after sunset. Starting in January 2019, the regime allowed the former residents of Darayya to visit their homes, under the condition they obtain these security permissions, and their visits ended at sunset. Regime forces prevented any locals from staying in their homes overnight.”

Syria Untold accompanied Walid to the Justice Department in Damascus to inquire about the fate of his house in Darayya, especially in relation to Law No. 10? Is his home subject to this law or not?

Wandering the halls of the Justice Department, we failed to get a definitive answer in regards to how Law No. 10 will affect houses in Darayya. We were then referred to the Real Estate Registry in the Sarouja district in downtown Damascus.

After waiting in a long queue, an employee shrugged her shoulders when asked and said: “We are yet to know the fate of the town of Darayya, as we haven’t yet received any instructions from ‘up high’ (meaning the authorities) in this regard.”

I insisted and asked the employee about Law No. 10, and how it affects ownership of people’s property. Would it indeed give reconstruction in Damascus a developed and pioneering image, as the local media has been telling us? Or would it, in reality, dispossess people of their property, just as the talks circulating among the general public say?

The employee was then overcome with visible confusion, as she shook her shoulders again and said, “I don’t know.”

Millions of refugees and displaced people will be forcibly deprived of their rightfully owned properties unless they produce proof of ownership.

Before we left the room, she stopped me to tell me all that all she knows as a lawyer working in this registry is that “Until now, the law has been shrouded with ambiguity. The legislators are asking people to certify their ownership of properties. These properties are already registered with us, and their owners have rights that are protected by the constitution. However, they are now asked to register them a second time, and this is an error that Law No. 10 insists on perpetuating.”

Darayya is not a slum town or an informal housing area. Most of the town is zoned and registered in the Land Registry Office. While most residents of slums areas, such as al-Lawan and al-Ikhlas, do not own deeds to properties. Most informal areas were never zoned or included in land registries before 2011.

We directed the question posed by the employee at Real Estate Registry about the motivation behind Law No. 10 and the problem it is attempting to address, to a lawyer specialized in property rights. “The gravity of this law lies in the fact that the legislators did not mention the reason for its enactment,” said Shaher, the 45-year-old lawyer and resident of Damascus, “Except wanting to construct massive buildings and malls, against the will of the residents of these areas, and without sufficient or clear reasons for doing so. The choice of areas is another ambiguity, as it also excluded many informal areas such as Mezzeh 86, and Ish al-Warwar, both of which suffer a very poor quality of services. Instead, the law only targeted the neighborhoods that had rebelled against the regime in 2011.”

The second danger in Law No. 10 is that millions of refugees and displaced people will be forcibly deprived of their rightfully owned properties unless they produce proof of ownership. Their property rights will be diminished due to the impossibility of obtaining the required documents. Thus, by force of law, they will lose the rights to their property.

Law No. 10 will also prohibit current owners from choosing their shares in housing units when they are completed. Instead, it grants administrative institutions overseeing the project, like the governorate and the municipality, the mandate to determine the current owners’ future shares. This opens the door to nepotism, intermediaries and bribes, which will play a role in determining such shares.

Al-Tadamon neighborhood; unrealistic rhetoric

The mandate of Law No. 10 did only cover industrial zones, but also informal areas around Damascus, including al-Tadamon. The Syrian opposition took control of the neighborhood in 2012. Later, the neighborhood fell under the control of Islamic State (ISIS) in 2015. The Syrian regime forces targeted the neighborhood with bombardment since 2012, damaging the building and causing destruction.

After the regime took control of al-Tadamon last May, and according to a several residents’ testimonies, most of the houses in the neighborhood had remained in good condition, but the regime prevented residents from returning to the area under the pretext that it was not safe yet.

Amina is a 21-year-old young woman who was displaced from the al-Tadamon neighborhood. “With the regime’s full control of the neighborhood, we were allowed to visit and inspect our homes,” She recounted to Syria Untold. “But we were prohibited from retrieving any of our belongings.”

Having lived in al-Sharabji quarter of al-Tadamon, Amina told us that she did not see any of the furniture or doors she left in the house. All of the neighborhood’s homes, she said, had been thoroughly pillaged.

The second stage came in the form of statements made by the Governor of Damascus, Bishr al-Sabban, who claimed that only 690 houses in al-Tadamon are inhabitable. As such, most of the houses were unsuitable and needed to be demolished. Many of the neighbourhood’s residents considered these statements to be exaggerated rhetoric.

The statements made by the Governorate of Damascus, and preventing the residents from returning to their homes, does not, in the view of our interviewees, reflect the regime’s concern for people’s safety. Instead, the regime’ goal is the takeover of the area and rezoning it. Under this pretext, al-Tadamon was no longer under the mandate of Law No. 3, which addresses conflict debris and restoration of damaged structures, but Law No. 10 which is concerned with reconstruction.

Al-Tadamon neighborhood is considered one of the largest informal areas in Damascus, and the people in such areas around Damascus do not have property deeds. Many have settled in these areas under housing permits, but the land there is mostly state-owned. The same applies to Al-Tadamon neighborhood, where displaced people from the occupied Golan have been living for four decades, in slums, and are now denied access to their homes. They may also be deprived of their right to return because they do not have the necessary paperwork. Soon, and upon the completion of Marota and Basilia projects, no housing units would be allocated to the residnts of al-Tadamon, because they do not have ownership deeds. To many, this is regarded as a grave injustice.

Industry workshops not surviving either

The horror of Law No. 10 is not limited to homeowners, but it extends to proprietors of industrial workshops as well. Abu Yousef is 56-year-old and he lives in the eastern districts of Damascus, in the vicinity of Abbasiyyin Square, where he also owns a ceramics workshop. He is among many manufacturers and artisans who have lost their workshops, and his shop used to provide livelihoods for seven workers and their families.

Abu Yousef gestured with his hands as he spoke to Syria Untold: “This area of the Qaboun neighborhood remained since 2011 under the control of the state (in reference to parts of Tishreen, Qaboun and western Harasta). It has been hit by many shells from all sides, but we insisted on staying here and carrying on with our work.”

Last October, the Ministry of Industry issued a notice to all industrialists, demanding the evacuation of all industrial workshops in the area under the pretext of rezoning it.

Abu Yousef informed us about a meeting in the Chamber of Industry, the relevant body tasked with protecting the rights and interests of industrialists in Damascus. An agreement was reached to form a joint committee in collaboration with the Real Estate Department. The committee would inspect the damages and demolish only the workshops which were more than 60% damaged, and spare the remaining workshops. This was especially pertinent as the majority of industrial workshops were damaged by no more than 15% as a result of military operations. The Governorate of Damascus was later provided with the findings of the committee's assessment detailing the structural integrity of these workshops, which demonstrated that the majority of them are operational in their current state.

“This area is not a slum, but an industrial zone registered in the official records since 1974,” Abu Yousef continued, “and we industrialists are willing to bear the costs of restoring it at our own expense, in exchange for staying on our property, which is our right according to law.” However, a decision was issued by the Ministry of Local Administration, stating that this area is within the scope of Law No. 10, and that all industrial workshops should be moved to the Adra Industrial City instead, whose infrastructure is essentially unfit for industrial work.

Abu Yousef concluded: “Then, bulldozers came with the support of the fourth armoured division, to turn our workshops into rubble, and now we stand on ruins and mourn them.”

Standing atop Mount Qasioun overlooking Damascus, one could see the stretches of the city’s eastern edges, where Law No. 10 had devoured the neighborhood of Qaboun. To the north, Decree No. 66 consumed the neighborhoods of al-Ikhlas, Basateen and Kafar Sousah, all the way to Darayya, and then to al-Tadamon neighborhood in the south.

A new fear is instilled in the hearts of Syrians despite the end of the military operations, and the fact that shells are not being dropped on the civilian population from above anymore while the warring parties continued exchanging accusations. Many are afraid of being dispossessed of their homes, properties and livelihood. Their dispossession will not be carried out by arms, but by the force of law this time. As such, Damascus today remains besieged by draconian legislation.