This article is part of a dossier in partnership between SyriaUntold and openDemocracy's North Africa West Asia page, exploring the emerging post-2011 Syrian cinema: its politics, production challenges, censorship, viewership, and where it may be heading next. This project is coordinated by Maya Abyad, Enrico De Angelis and Walid el-Houri, and supported by Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

The National Film Organization has controlled the financing and the production of Syrian films as well as their distribution since its establishment in 1963, and continued to do so until its monopoly was shattered with the eruption of mass movements in Syria in 2011. This domination was a factor in barring Syrian spectators from Syrian cinema, with the exception of a small group of intellectuals, film aficionados, and artists. While most of the films produced since then were not projected in local movie theatres, most were allowed to participate in Arab and Western festivals frequented by cultural elites, to the detriment of their local distribution. There are certain special cases, however, when other forces are at play, where such a schizoid state of affairs is suspended.

The control over local movie production began to take hold with the accession to power of the Ba’ath party in 1963, when the Syrian State monopolised the cinema industry and the production and distribution of films through the National Film Organization of the Ministry of Culture. In a parallel move, the import and distribution of foreign films, as well as the export of Syrian films to foreign markets, were made exclusive to the Organization through the state decree number 2543.

However, despite the near-total control that the National Film Organization exercised on directors, whether through control of funding or content, it offered opportunities to a number of Syrian and Arab directors to apply for funding for their film projects. After a project is approved, the NFO offered further assistance in the production process and all the way through to screening, which led some to consider the period between the late 60s and the 80s the golden era of Syrian film production.

With the rise to power of Hafez al-Assad in 1970, the operations of the National Film Organization were further scrutinized. More restrictions were imposed on filmmakers to ensure conformity with the official Ba'athist ideology, which prompted some directors to circumvent that policy by offering films rich in symbolic metaphors and temporal abstraction in order to tackle the social and political issues in Syria. Such films include Nujum al-Nahar (“Daytime Stars”) by Osama Mohamed, Al-Tirhal (“Picking Up and Leaving”) by Raymond Boutros, Ahlam al-Madina (“City Dreams”) by Mohamed Malas and many other films that participated in international festivals, but which were banned or not shown locally to the Syrian public, as in the case of Nujum al-Nahar. The film was funded by the National Film Organization and represented Syria in many festivals but was banned locally, following a decision from Hafez al-Assad, according to some reports.

The National Film Organization also had a say in the content of the film and the choice of director, while ultimately controlling the production of the film at every step and restricting the funding to directors who mostly pursued their studies abroad, especially given the fact that a film school does not exist to this day in Syria. All these factors made the National Film Organization the ultimate controller of both the cinematic discourse in Syria and its quality, which is always subject to the amount of funding allocated. This was reinforced by the lack of interest by external or private parties in financing Syrian films, which led to a decline in the level and the quality of these films.

In an interview conducted in 2008, Syrian director Omar Amiralay blamed the deterioration of the Syrian film industry first on the directors themselves, in as much as they consented to the conditions of the organization in order to obtain funding for their films. Secondly, according to Amiralay, it became clear that the organization through its director Mohammed Al-Ahmad had the utmost contempt and despise towards Syrian cinema, a fact barely hidden, given the director’s frequent and vitriolic campaigns against the authors and writers of Syrian cinema.

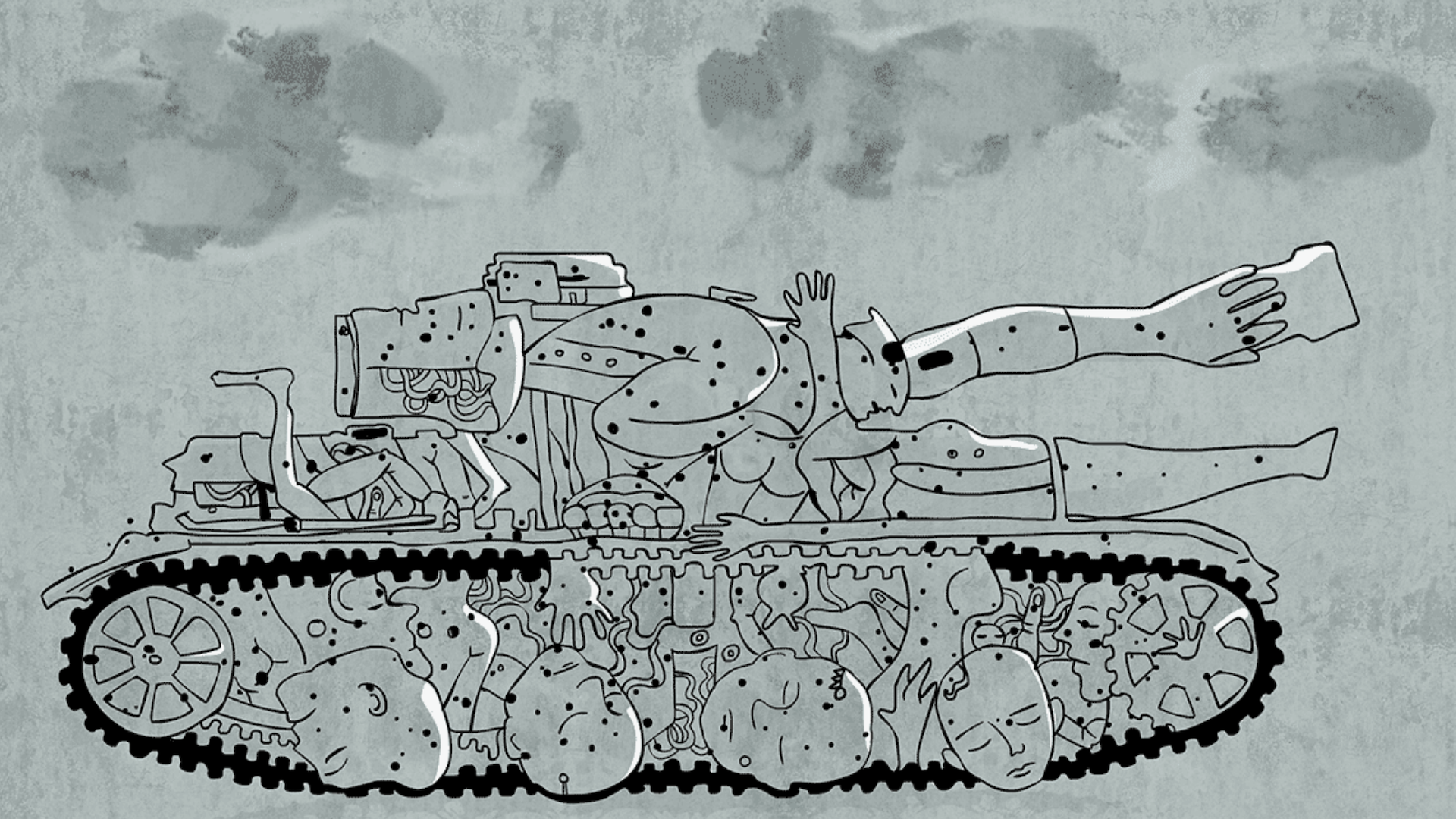

A still from Ziad Kalthoum's 'Taste of Cement' (2017), about Syrian construction workers in Beirut.

A still from Ziad Kalthoum's 'Taste of Cement' (2017), about Syrian construction workers in Beirut.A cinema and its audience

With the dispersals and displacements of Syrians all over, and the various political polarizations and radical differences that have come to the fore in the wake of the peaceful mass rallies, it has become more difficult to identify the audience of Syrian cinema, the funders, the distributors, and those responsible for the production. In the increasing absence of the previously controlling role of the regime through its National Film Organization, pro-opposition films began receiving funding through foreign cultural bodies and several international organizations and this became a way for some Syrian filmmakers to do without the Organization.

Specifically, Syrian documentaries have become a source of global interest as they relate the Syrian story, and they have received foreign support and funding often at the expense of the feature film. It can be said that this has led to the expansion of the documentary audience to include new categories of viewers, mostly foreign or European.

It is difficult today to determine the audience of Syrian cinema or its distribution channels, but an overview of the places where non-regime affiliated Syrian films are screened shows that they are distributed under the supervision of foreign institutions, which ensure its presence in festivals and screening locations in which most audiences are non-Syrian.

Writer and playwright Amr Sawah claims there is no Syrian audience for Syrian films today and he further establishes a distinction between an audience that resides inside Syria, and which has slightly increased with the internal migration movements and the dense urban concentration, and an audience of Syrians residing abroad which does not eagerly attend the screening of Syrian films, most of which are documentary films.

According to Ziad Kalthoum, director of the documentary "Taste of Cement," the Syrian audience can be classified into two groups, one pro-revolution and the other pro-regime, adding that after the outbreak of the revolution, over 90% of the Syrian films are in effect documentaries, with nearly no feature films. Kalthoum claims that the Syrian public abroad is interested in everything that concerns its story, while the European public also finds interest in these films as a way of knowing what is taking place in Syria.

Related articles

05 June 2019

The exceptional Syrian situation that has been unfolding since spring 2011 prompted Syrians artists to ask radical questions about the meaning of identity, belonging and artistic work. These questions were...

In one of her interviews, Syrian director and writer Wahat al-Raheb contends that before the revolution, the Syrian movie goers were greatly enthused over locally produced films, adding that her first feature, Ru’aa Haalima (“A Dreamer’s Visions”), which was produced by the National Film Organization in 2007 is a good case in point. The film recounts the story of a dreamy girl named Jamila in a period of defeats, violence, and despair. Jamila searches for a cause through committed action during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and eventually joins the resistance, but she ends up reaching what is most important, namely self-discovery. According to al-Raheb, the production expenses of the film were later covered from its screening in the province of Latakia without any prior publicity as was reported by the National Film Organization, and even profits were made, a fact that, as al-Raheb stresses, shows that the Syrian public prior to the revolution and war constituted a vibrant and interactive audience through all its segments and age groups, and that it had real interest in local films.

For many artists, the death of Hafez al-Assad in 2000, followed by Bashar’s access to power, sparked a hope that the son would be able to lead the country towards a free and democratic future in which the cultural and cinematic landscape may change, while opening new horizons that would loosen the hold of the National Film Organization on the production of Syrian films and its restriction to specific directors. And indeed, the movement that ensued saw the establishment of cultural and political salons in which lively discussions about the future of Syria were held, in addition to cultural debates and screenings of both Syrian and non-Syrian films. However, this movement was soon crushed, a number of activists were imprisoned and the artists and directors in favour of change were neutralized.

Despite this, a new generation of Syrian directors emerged, some of whom included Mohamed Abdel Aziz, the director of the film Dimashq, ma’a Hubbi (“Damascus, With Love”), Nidal Debs, the director of Taht al-Saqf (“Under The Roof”), and Joude Said, the director of Marra Ukhra (“Once Again”). Reem Ali also presented her documentary titled Zabad (“Froth”), and Nabil Al Maleh who directed a series of films and documentaries on women that were shown only to a limited audience at the Family Affairs Organization. The majority of these films did not reach Syrian viewers because most were shown only to a selected audience or screened in festivals abroad, as was the case for both Reem Ali's film and Nabil Al Maleh's documentaries.

These reasons explain the estrangement of Syrian audiences from the cinematic production that belongs to them and tackles their own issues. Their own daily stories were counterintuitively presented to audiences other than themselves. Instead, only those films that fit the regime's ideology and its issues were promoted and presented to the Syrian public.