This article is part of a dossier in partnership between SyriaUntold and openDemocracy's North Africa West Asia page, exploring the emerging post-2011 Syrian cinema: its politics, production challenges, censorship, viewership, and where it may be heading next. This project is coordinated by Maya Abyad, Enrico De Angelis and Walid el-Houri, and supported by Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

This article aims to draw a comparison between the Lebanese cinema of the 1970s and the Syrian cinema after 2011 in order to identify some issues raised by the contemporary form of political cinema. In both cases, the films take a stand against war, repression, and intimidation. Their political impact, however, has mutated.

In the Arab world, two main phases redesigned the relationship between cinema production and politics. The first, after the 1967 defeat to Israel, saw the emergence of a new generation of Arab filmmakers and artists who gathered in Damascus and Cairo to find another way of creating that was more in line with their ideals.

It led to the birth of the "Cinema al-Shabab" (Young Cinema) or "Cinema al-badil" (Alternative Cinema). In Lebanon, in 1975, the so-called "New Lebanese Cinema" emerged, led by young filmmakers. They were not necessarily well-trained in the field but they had new ideas to convey and were ideologically driven. They all dreamed of making fiction films, but also felt a necessity to make documentary films. These younger filmmakers sold their products to international TV channels in order to inform. These films can be considered films of mobilization.

The 2011 uprisings marked another turning point, as new forms of cinematic language and style began to emerge. I will take here Syria as a case example — also because of the neat disruption between the models of production that existed before, and after, the uprising.

I will refer to filmmakers that oppose the Syrian regime and see cinema as a mean to express the ideas and the aims of the Syrian revolution.

Most of them were not active filmmakers under the regime before 2011, when cinematographic creation was always rigorously controlled. Instead, they started filming in the chaos of the war. While opposing the regime and its repression, many of those young filmmakers also opposed the generation of their predecessors.

The forms they use defy traditional cinema. Often shot in the spur of the moment, with limited equipment and sometimes without any cinematographic experience, these films are mainly documentaries. Even if these filmmakers did not produce a collective cinema manifesto, their films all have something in common.

Firstly, they all take the forms of personal narratives of the directors and/or their friends and relatives, almost as a way to exist individually in the heart of chaos.

And secondly, they mainly circulate in festivals and are rarely distributed beyond them, and so are watched mainly by the elites.

A cinema at the service of ideologies

During the Lebanese civil war, a new generation of filmmakers—especially leftists—decided to film for the oppressed: the Palestinians, the Southern Lebanese, and displaced people in general. Without refusing to showcase the reality of their first-person experience, the young filmmakers of the 1970s did however feel the urgency of putting their images primarily at the service of those being filmed: peoples torn,, individuals crushed, or orphans who did not have any chance of expressing themselves.

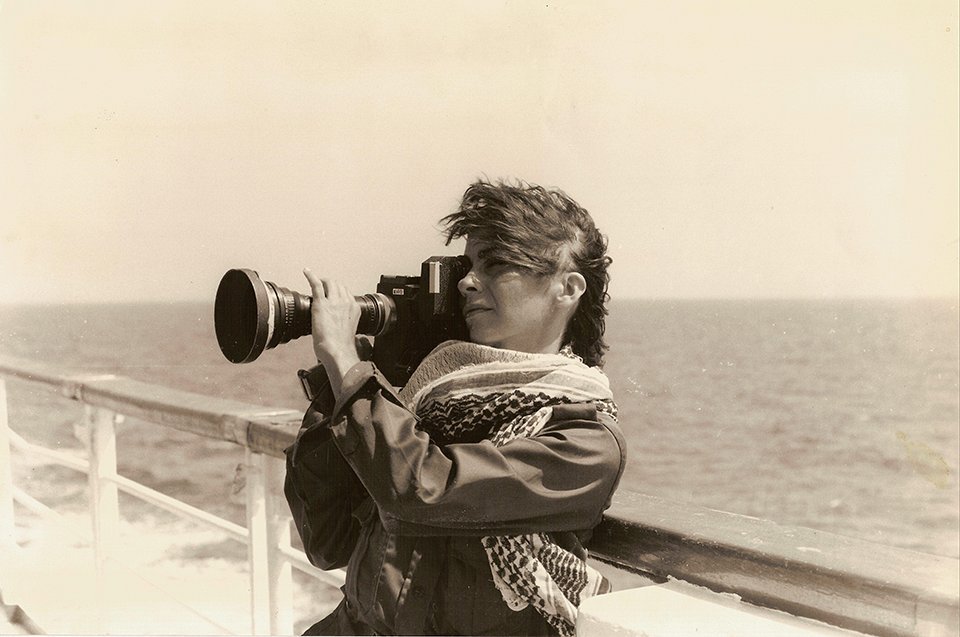

In the 1970s and 1980s, television channels and political groups were the main producers of this type of film. Meanwhile, these films were much more than mere war reportage. Documentary filmmakers such as Maroun Bagdadi, Jocelyne Saab or Randa Chahal Sabbagh had to create a new cinematographic language in order to voice their despair. Even when produced for international TV channels, these films stood for the “we”: the filmmakers spoke from their homeland, for their people. The option of selling the films to European television was moreover perceived as a good opportunity to make politics: Western mass media made it more possible to experiment with new styles, new ways of telling facts, and alternative discourses. This was the explicit aim of Jocelyne Saab, the most prolific filmmaker of this generation, who, after the censorship of her short documentary Palestinian Women, began to produce her own films independently. Saab started to sell her documentaries to French, German, and Swedish television channels, among others.

This idea of speaking for a “we” has become less predominant in contemporary political Arab cinema. In the context of the Syrian civil war, young filmmakers privilege a first-person testimony, whereby the camera becomes an extension of the filmmaker – who is often the main character of his or her film. More personal, these films refuse to assume a gaze distant from the war. Rather, they propose another form of political cinema — in a way much more immersive, but at the same time more problematic when it comes to identifying a more inclusive and collective political subject.

Without assuming that distant gaze, the grammar of these films often tend to separate the filmmaker and/or a filmed group of individuals from the rest of the people.

This impulse towards self-reflexivity appears to be strictly connected with recent technological changes. In the era of the network, the evidence-image is there, always accessible at the click of a mouse.

In response to the overflow of images that have documented and counter-documented the evolution of the war, filmmakers seem to turn into the private space of an individual or a group of individuals as the only way through which an authentic narrative can be found.

A generational gap

The documentary films of the 1970s produced during the Lebanese civil war already refused the classic documentary form as neutral or objective. In view of the image of a collapsing city, many of these films staged a voiceover in the first person, because the figure of the director cannot be completely merged into the filmed scene.

In some cases, the filmmaker appears in the film as a personification of the drama caused by the war — like Jocelyne Saab did by standing in the middle of the ruins of her house in “Beirut madinati” (Beirut, My City, 1982). However, the “I,” in this case, is still a “we”: it is Lebanon and its people. Randa Chahal Sabbagh in “Khatwa khatwa” (Step by Step, 1978) or Jocelyne Saab in “Lettre de Beyrouth” (Letter From Beirut, 1978), are filming Beirut’s walls as if the city was writing its own testament.

In the contemporary Syrian case, individual narratives, no matter how strong, do not let us think about the situation as a whole, and therefore, we can think, to mobilize. The more personal prism does not encourage the viewer to take a stand against a reality in which violence is denounced. The political background generally does not appear in the frame. The chosen frames narrate certain realities (repression, violence, exile), but they do not give enough space to a more collective and wider dimension, which is a prerequisite when it comes to shaping a collective political subjectivity, and advocate for a specific political stance.

Among several questions raised in the first person, that of exile comes up again and again. However, particular realities replace the universal questioning on the condition of exile — as for example a film like “Lettre d’un temps d’exil,” by Borhane Alaouié (1988), did by talking in the name of a fictionalized “I” that opens to collective issues.

In “Maskoon” (Haunted, 2013), Liwaa Yazji focuses on the link between living spaces and those who occupy them. In exile, filming Syria through the images on her computer screen while calling her parents via Skype, she reports the resilience of those who have decided to stay. Resilience is often at the heart of these movies. It illustrates an act of resistance. It is also the case of Yaser Kassab who, in “Ala hafet al-Hayat”* (On the Edge of Life, 2017), narrates the pain of his exile in Turkey with his wife Rima, while many members of his family have decided to stay.

The need to continue to participate lingers. Milad Amin, in “Ard al-Manshar”* (Land of Doom, 2017), tells from Beirut the story of his friend Ghith, who is still in Aleppo during the siege. Both of them activists, their relationship is at the core of the story. The two men communicate through Skype, and the images filmed by Ghith arrive to Beirut sparingly, at the mercy of the connection.

It is important, for those who left, to prove that they have not abandoned any of their beliefs. Some questions seem to be central to the core of this production. How long will it take before we have to surrender to exile? Until when will we be able to resist against our enemies?

These questions do not have clear answers.

In “300 Meel”* (300 Miles, 2016), Orwa al-Moktad follows a group of resistance fighters in Aleppo for two years. Rather than the historical context, it's the psychological evolution of the characters on which the film focuses more, repeatedly questioning the meaning of the revolution and its possible outcomes.

In “194. Nehna, Walad al-Mokhayaam”* (194. Us, Children of the camp, 2017), Samer Salameh narrates his departure for training in the Palestine Liberation Army in Syria on the eve of the war. He films himself, cutting his shock of hair, and announces in a voiceover: "I have no choice. [...] I leave my camera, recording on its own, while I fall into the well of my story.” This camera will reappear again and again as a character in the movie. The film narrative, one more time, is a chronicle of a daily life — in this case, within the Palestinian community in Syria. Filming to exist, to demonstrate the destruction of personal lives. The approach seems to be induced by the horror of a war that crushes everything in its path, without distinction.

In “Baladna al-Raheeb”* (Our Terrible Country, 2014), by Mohamed Ali Atassi and Ziad Homsi, intellectual and dissident Yassin al-Haj Saleh denounces the separation walls between intellectuals and the society in Baathist Syria.

The whole drama of contemporary Syrian cinema is here exposed. The decision by filmmakers like Orwa al-Mokdad, Talal Derki or Saeed al-Batal to follow the fighters at the front clearly responds to the need of creating a convergence between the people and the ideas. However, the impossible universalization of the themes of these films appears to condemn these efforts to an inevitable failure. The finite and strict adherence to an individual point of view makes it difficult to develop a more inclusive and collective narrative.

Moreover, how can these films resonate in the society to which the filmmakers belong, if they do not reach those they are addressing?

This marks a notable difference with the films produced during the Lebanese war that were often bought by international TV channels, broadcast as part of very popular TV programs, and seen by the Lebanese diaspora — who remember these films until now.

Art for art?

It is quite interesting to note the extent to which these films, produced in Syria since 2012, follow similar patterns and dynamics.

The production of these films was achieved due to the establishment of new institutions specifically dedicated to supporting the production of Syrian movies in the context of the uprising. Among them, Bidayyat, an association founded by Syrians in Beirut in 2013 (with the support of the German fund Heinrich Böll), is one of the most relevant. On the association’s website, Bidayyat sets out its objectives: "Bidayyat hopes to cast light on the complexity and richness of the region's sociological reality through a language of documentary cinema which interrogates reality just as much as it records it, which privileges art over propaganda, people over rulers and revolution over the status quo."

The whole program of the films we are discussing is included here. Reading it, we could ask ourselves: who are the “people” these films describe, which “revolution” do they illustrate, and who is this “art” addressing?

The contrast with the cultural and ideological background of the documentary films produced during the 1970s in Lebanon could not be more evident. At that time, resistance is omnipresent in most of the documentary production. The main issue is giving voice to those whose existence is denied, and in particular the Palestinians.

The filmmaker vanishes behind his or her camera to offer a wide angle on the misery of the committed peoples. Nabiha Lofti, a student at Cairo’s College of Cinematography, was hired in 1974 by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to produce a documentary on women administrating the refugee camp of Tel al-Zaatar. Following several trips and close work with the wives and mothers of those at the front, she faces the distress provoked by the massacres at the hands of the Maronite militias.

However, the filmmaker soon decides to aim her camera on the survivors and their children.

The use of freeze frames reinforces them as symbols of resistance. The filmmaker seems to take a step back, does not impose her presence: she only seeks to recount a disarming reality where only the words of the victims can be conveyed.

The same impulse can be found in other productions of that time, like Heiny Srour's “Layla wa al-dhi’ab” (“Leila and the Wolves,” 1988), or the films of Jean Chamoun, who began his career as a filmmaker in the ranks of the PLO.

Today, the purpose behind films shot in the war seems to have changed. From an intolerable need to inform, the film has become the aesthetic construction of an individuality in resistance, legitimized by the presence of the director and/or their friends and relatives on the ground.

Today, the primary necessity is no longer to document the invisible, but rather to expose a personal perception of an over-mediated conflict. Instead of mobilizing to defend a cause or to denounce the injustice of a situation lived by a people or a group of people, these films tend to stage individual histories in a setting of war, at the expense of a factual documentation of the wider history.

Assuming a complete subjectivity, some filmmakers stand out their films from the space and time of the conflict they are trapped in and share a personal reflection that renders universal, but also decontextualizes, the war for the misinformed spectator. The artistic film form seems then to prevail on the political stances.

The main principle of Ghiath Ayoub and Saeed al-Batal’s film “Lissa ‘am tusajjil”* (Still Recording, 2018) illustrates this dynamic. At the beginning of the film, the two filmmakers gather and ask their comrades, fighters in the Free Syrian Army, to go filming everywhere as soon as they feel that the moment could be the essence of a potential film. Throughout the film, the process of making the film is put forward: Saeed plays with the focus of the image; the issue of the film production is fully discussed in the image while the presence of the camera is pervasive.

From 450 hours of film footage, the filmmakers thought it important to put forward a dominant meta-discourse on the construction of a cinema-testimony, and on the audacity of those who do it, through a two-hour film. This position of the “artist-resistant” is not new. But if the legitimacy of these images and cameramen at the heart of the conflict is indisputable, the construction of the cinematic dialogue can be discussed. By imposing a total subjectivity on the topic of the film, the filmmakers risk to stand alone in front of the world, and cannot proclaim themselves as the representatives of anyone.

These filmmakers do not aim to explain the reality context and its background. In “The War Show” (2016), Obeida Zytoon repeats throughout his film that what the regime "fears the most is someone with a camera.” The existence of the film, even before the political discourse that it carries, is itself proof of the resistant quality of the one holding the camera.

During the Lebanese civil war, on the contrary, the affirmation of a political stance was not so much in the fact of being on the ground and filming, but in being able of showing as quickly as possible the reality of the fighting. The challenge was to transform the general perception of the conflict. In Syria, filmmakers do not invest their films for the same mission. Considering the time of its release and its very limited distribution, the film instead aims to produce a chronicle of specific, personal aspects and angles of the war.

Who do these film address? The audience of contemporary Syrian filmmakers is not the same as the films distributed in mainstream channels during the 1970s. [1]

Even more important, the images are not chosen or mounted for the sake of a unitary political and artistic discourse as they were in the militant films of the Lebanese war.

Their places of recognition are the major international film festivals - Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Rotterdam, Locarno – mostly for a European elite sensitized to the issue of documentary creation, and in search of an artistic avant-garde. Common Syrian people are not expected to be seated in front of the cinema screens of Western capitals.

New Syrian cinema is booming today, and its artistic and documentary value cannot be denied. In addition to documentary productions, there is a growing number of fictional films that also find their place in international markets. In 2018, Gaya Jiji was awarded at Cannes for “Mon tissu préféré” (My Favorite Fabric) and Soudade Kaadan was awarded in Venice for “Yom Adaatou Zouli” (The Day I Lost My Shadow, 2018).

The question that remains is on the durability of an experimental creative process, capable of going beyond the limits that it has drawn itself, and on its political value today.

[1] Most of the above-mentioned films were first shown on television before an international festival tour.*Films marked with an asterisk were produced by Bidayyat for Audiovisual Arts or benefited from the Bidayyat's documentary grant.