This article is published as part of the “Prospects of Secularism in Syria” series in collaboration with Salon Syria and Jadaliyya. The full series in Arabic can also be found here.

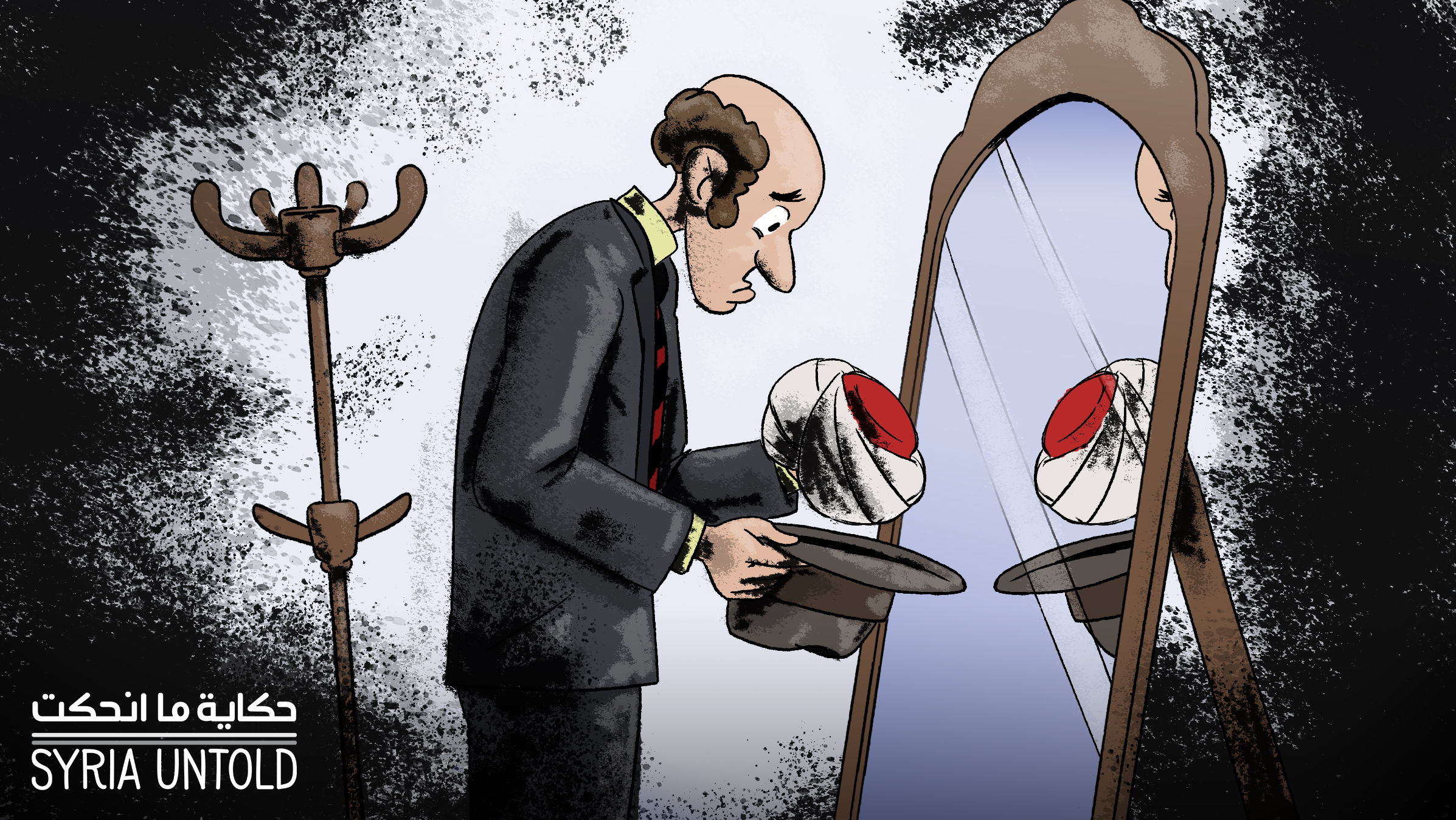

Secular discourse in Syria has been one of the victims of the Syrian revolution. Why? The regime, Islamic factions, Gulf countries and Turkey all collaborated to chip away at this discourse, excluding it from the table of discussion. And while the regime used secularism as a political playing-card, a cosmetic decoration without substance; opposition factions marginalized the concept of secularism, considering it synonymous with atheism and apostasy.

But even before the outbreak of the revolution, there was a heated debate between four intellectual currents that addressed the issue of secularism: the Islamic and the regime, majoritarian and minority.

The Islamic current and secularism

The first was the Islamic current, with which there is no appeasement with secular thought. This current was led by intellectual clerics and jurists, in addition to other ordinary people and populists.

All of them took the easy way of citing holy scripture in order to make the claim that secularism is a Western product with the aim of destroying Islam.

Some even went so far as to say that secularism is the product of some Jewish movement that “wants to spread atheism around the world and use secularism as a cover,” as Abdelrahman Hasan Habannakeh once said.

Related articles

18 August 2018

Syrian secularists, and moreover the concept of secularism, are under attack online and on the ground. Joseph Daher takes a critical look at recent efforts to discredit the contribution of...

The regime current

The regime current made a historic settlement with the Islamic current—headed by the late sheikh, Mohammed Saeed Ramadan al-Bouti—whereby Islamists would leave alone the political and economic spheres to the regime so long as the regime would leave cultural and social spheres to the clerics.

This agreement gained strength after the international pressure on the Syrian regime that followed the US occupation of Iraq, and Syria’s role in sending jihadist fighters to fight against US forces and to commit some of the most heinous sectarian massacres.

As a result of this international pressure, the authorities responded with a combination of nationalism and religious rhetoric.

Before the revolution, we observed a significant rise in religious discourse in the political performances of decision-makers in Syria—and especially during the crisis following the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri and the subsequent external pressures on the Syrian government—along with an increasing courting between between the government and the pillars of the more closed religious establishment. This preceded radical unrest from Islamist groups, culminating in the burning down and destruction of the Danish and Norwegian embassies in February 2006.

This strong alliance between the regime and the clerics had to clear the way of obstacles that might stand in its way. So, open-minded clerics, such as Mohammed Shahrour and Dr. Mashouq al-Khaznawi, were attacked. Shahrour repeatedly said that “Islam does not contradict secularism,” ans that it “considers people as equal, and are only distinguished by their good deeds.”

He clearly stated: “Putting the article of ‘Islam is the religion of the state’ in any constitution is meaningless, and is a fallacy to control the fate of people. It is better to focus on the state, institutions and laws so that the likes of Merkel and Trudeau can rule through institutions and not through the figures themselves.”

Before he was killed, al-Khaznawi explicitly called for secularism, or what he defined as “ultimately, the separation of religion from the state.” Al-Khaznawi called secularism a “demand that serves both sides,” in that a "distancing of religion from the state and political action serves to protect religion itself, its status, values and higher principles.”

The call for secularism, in al-Khaznawi’s opinion, could be associated with the idea of “no compulsion in religion” and the idea of humanitarian brotherhood, which he considered a key part of the discussion.

Al-Khaznawi worked on “finding commonalities between people of various intellectual, political and social orientations, especially between the people of the same nation.”

In the end, Shahrour had to flee abroad along with his rationalist doctrine, while al-Khaznawi died as a result of torture in the mid-2000s.

The majoritarian current that ‘deifies the people'

The third current, majoritarian in nature, is comprised of a broad spectrum of Syrian intellectuals who deify “the people” and seek to appease the “majority.”

These intellectuals called for a soft secularism, without teeth, that would remain in the upper echelons of the state without descending to the people in society. These people consider secularism to be something that serves dictatorship and deprives the majority (itself mainly Sunni) of freedom of expression because it seeks to separate religion from institutions and considers that that priority should be given to humans and not religion and its institutions, people or sects.

They want rid this gentle secularism to be wrested from the clutches of sour secularists, to instead make it acceptable to the majority. So, they say that secularism does not contradict with Islam and seek its origins in Arab-Islamic history.

The minority current

The fourth is the minority current that calls for a non-ideological state that maintains the same distance from all religions and belief systems, and does not interfere with the content of religious beliefs. It does not regulate religions and has to treat all religions and philosophical doctrines equally, without endorsing any one over another. It does not only guarantee freedom of belief, but also guarantees the freedom to exercise religious rites, protecting individuals and guaranteeing their free choice to have a religion orientation (or not).

This current is also keen that no group or sect is able to impose its religious or sectarian identity or affiliation, and in particular, forcefully divide individuals according to their family origins.

Areas under the regime’s control were no better off. The regime, which often boasts of its secularity, had to respond to this Islamic tide. We can clearly see that in the controversial law regarding the role of the Ministry of Endowments, which was considered by many Ba'athists and regime supporters as something that 'reinforces religious divides in the country and allows the ministry to have absolute power over a number of the state’s joints, turning it in to a ministry with no partners in decision-making.'

Secularism in revolution

With the rise of the Syrian revolution, the Islamic current gained in strength and power, both in areas controlled by the opposition as well as the regime. Referring to secularism became a hated matter—a taboo, even. It became a charge in and of itself, in areas controlled by the opposition factions, that secularism was somehow equal to blasphemy or apostasy.

Syrian secular intellectuals, or intellectuals friendly to the concept of secularism, abandoned their ideas and started using the term “civil” rather than “secular.” Some even sought to play the role of religious reformers instead of being critics, so, they raised the issue of “Islamic reform,” reverting back to more than a century ago in their thoughts and finding themselves among the likes of Mohammed Abdo and Mohammed Rashid Reda, at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century.

Areas under the regime’s control were no better off. The regime, which often boasts of its secularity, had to respond to this Islamic tide. We can clearly see that in the controversial law regarding the role of the Ministry of Endowments, which was considered by many Ba'athists and regime supporters as something that “reinforces religious divides in the country and allows the ministry to have absolute power over a number of the state’s joints, turning it in to a ministry with no partners in decision-making.”

Not only did the regime bow to this Islamic expansion, it also made concessions to Shia authorities and Christian churches, transforming the country—and even individual cities—into a patchwork of different states and cities.

In Damascus, for example, lifestyles in Qasaa and Bab Touma are different than that in al-Maidan, while the lifestyles in those areas are yet again different to those in al-Amin or Sayeda Zeinab.

The result has been the strengthening of social divisions between various components that make up the Syrian nation.

The state of Syrian secularism today

We can conclude that the state of secularism in Syria today is worse than it was a decade ago, or even before that. Syria has always known some sort of transparent secularism since its disengagement from the Ottoman Empire. Although this was not secularism in name, it was clear and lenient and no one objected to it. However, today Syria finds itself in much worse shape.

Many of those who claim they are secular are in fact in the same ranks with the regime, supporting its libertinism against the Syrian people—whether because of a fear that Islamists will overrun the country, or because they still cling to desperate leftist positions that are based on reaction rather than initiatives and action.

On the other hand, many of the intellectuals abandoned their secularity, claiming that now is not the time for theoretical and philosophical luxuries but for real change on the ground.

We will need a few more years yet before we can raise the issue so it can be discussed seriously and fruitfully. Nevertheless, raising any proposal for Syria’s future that leaves out the issue secularism would be another step toward alienating the country from modernity, democracy and cohabitation.

Secularism is a necessity in order to produce a modern, national state in contrast to a non-state, tyranny, violence and oppression. Secularism is the most important tool for Syrians to establish unity based on plurality and diversity.

Let’s also keep in mind that secularism is not value judgment, but a method of thought and life that considers human beings to be the essence of the issue as opposed to thought, belief or religion. This alone makes societal unity a sound place for life, interaction, production and development.

Perhaps the best epilogue is Syrian intellect Jahd al-Karim al-Jibaai’s claim that secularism is “not an external characteristic that we arbitrarily apply on a state or arbitrarily take away from it.”

“It is not a self-value judgement that secularist use to describe the state, but rather a rule of reality that is related to the foundation of the modern national state and its principles,” he said. “It is not a cultural choice or an ideological bias, except on the individual level. A national state is either secular or not a national state or even a state in the first place. This is not about the reality of difference and diversity religiously and ethnically, but about the essence of the modern state, which is basically a state of rights and law.”