Despite the recent circular from the Syrian government, forbidding all gatherings including funeral services and wakes, which applies to Ba’ath Party officials and ministers just as it does ordinary citizens, people were still flooding the streets of the rural Latakia town of Safita (at the time of writing).

People in the streets were served cups of bitter coffee and sweet tea as they waited to offer their condolences for the death of former Syrian Minister of Defense General Ali Habib.

Since the children of the late minister are all doctors and engineers, one would assume they’d be aware of the government’s instructions to ban gatherings and the potential high risks of people going outside at present. However, it seems that in Syria’s coastal areas, society survives on sarcasm, disbelief and derision—despite the potential havoc that might overwhelm the country in case of a widespread coronavirus outbreak.

Local police did not have sufficient authority to shut down the gathering in Safita, although they have been known to disperse gatherings in other areas. For instance, police suspended condolences two days before they ended in the village of Bustan al-Hamam, in the hills above above Latakia's Baniyas, as people paid their respects. In other areas, inhabitants voluntarily cancelled funeral services—like in Tartous, where the family of engineer Bassem Ali in Tartous announced that they would be receiving condolences for their mother’s death over the phone and social media in the interests of the “safety of the beloved mourners…and in compliance with the [government’s] decision.”

Massive gatherings have continued elsewhere, though, and not just for funeral services. After a ban on gatherings in front of bakeries, people instead started queueing to buy bread from authorised dealers, while the hustle and bustle in the markets and the streets has begun to dissipate.

Even so, the scenes aren’t all that different from what's been happening on the Syrian coast. In general, Syrians seem less willing to comply with the government's directives than was first expected—the government even had to introduce a mandatory curfew on March 21 to stop people from going outside.

If the people trusted their institutions, and if those institutions respected themselves, we wouldn’t be where we are today.

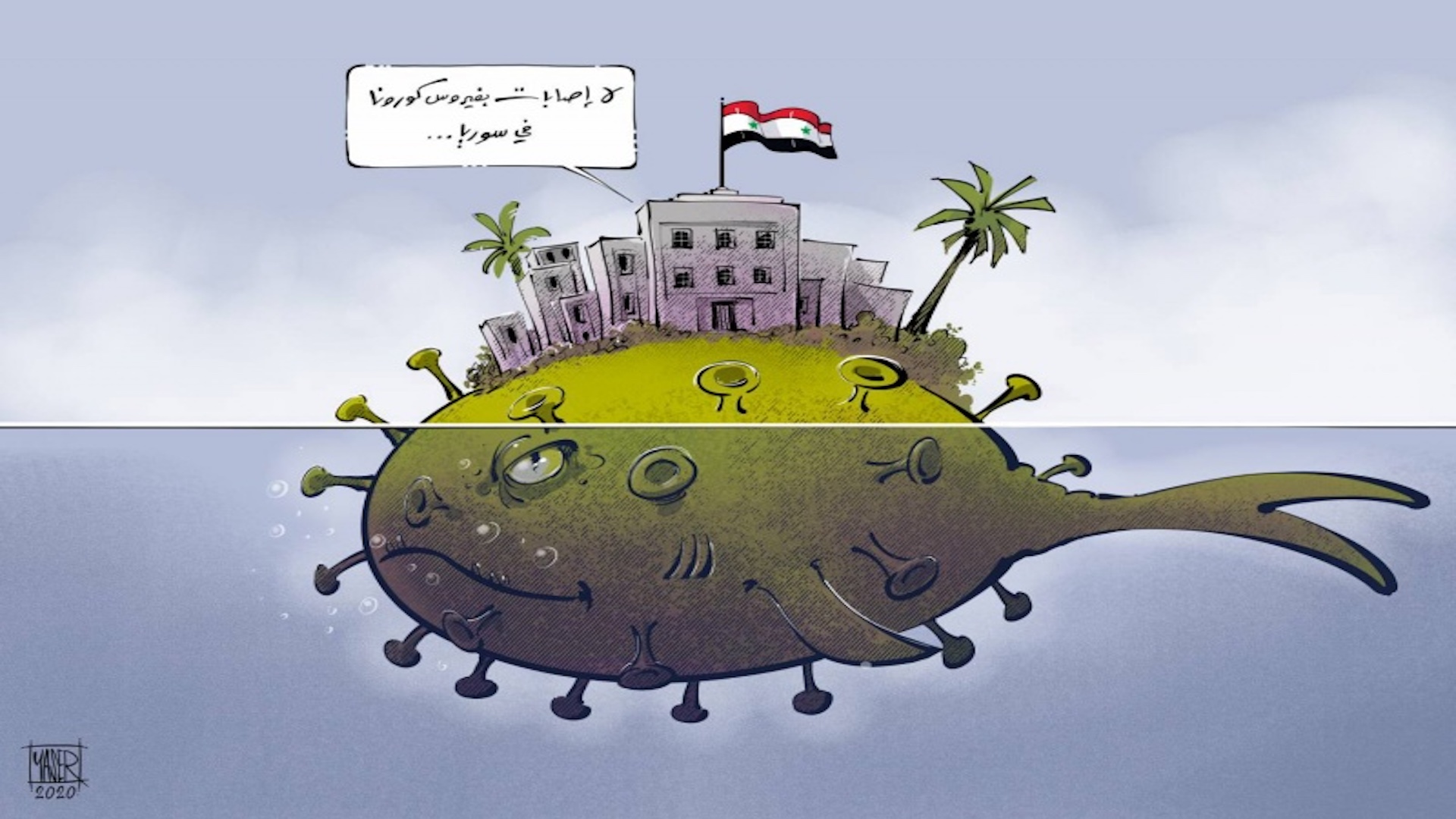

Is the Syrian government lying?

Earlier this week, Syria's Ministry of Health finally announced the first COVID-19 case on Syrian soil after weeks of statements, delays and obfuscations. Long before the official announcement, Syrians were taking to social media either expressing their doubts about the government’s statements, or putting their faith in them.

Those discrediting the statements said that Syria did not close its borders with neighbouring countries—such as Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan—until the virus had actually reached them. Therefore, they said, it was highly likely there were more cases, cases that the government and Ministry of Health were hiding. At the time, Damascus International Airport was still welcoming dozens of flights from Iran and other countries where the virus had already taken root, and without conducting accurate testing.

The last plane from Tehran, a Cham Wings flight carrying 140 passengers, landed in Damascus before the airport was shut. All its passengers were transferred to a quarantine centre in Aldweir, near Damascus. The centre posted several photos revealing the deteriorating situation inside because of its inability to provide adequate quarantine conditions, due to overcrowding and a lack of equipment.

Many didn’t believe the Syrian government's statement that there was only one COVID-19 case in Syria. Damascus has subsequently acknowledged as many as five case sin the country since then.

A young man living in Damascus, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told SyriaUntold that although COVID-19 “started spreading about a month ago, causing global panic…the authorities continued with their policy of denial, rather than beefing up awareness-raising campaigns.”

“If the people trusted their institutions, and if those institutions respected themselves, we wouldn’t be where we are today,” he added.

Dr. Layla, a respiratory disease specialist who asked that her real name be withheld in this report, believes the government's claims that there is only one coronavirus case in Syria currently.

“There are several types of pneumonia and, every year, hundreds of people are infected during winter. Some of them recover; others die. Coronavirus is one type of pneumonia, and the virus itself has several different strains," she explained.

The doctor argues that because of the way the Syrian authorities have disposed of the bodies of recent pneumonia victims, there is little to suggest they died of COVID-19.

Not everyone agrees, and rumours of COVID-19 deaths abound. One recent story claimed that a children’s hospital in Latakia hid the death of 15 children due to coronavirus—although it was not possible to independently verify the allegations, and no obituaries for the children were issued around the city.

Ahmad al-Farra, from the Children and Obstetrics Hospital in Latakia, denied the allegations.

“Three children died in the city within the space of a week because of pneumonia, congenital heart disease that led to heart failure, and sepsis in the lungs, rather than coronavirus,” he claimed. “Strict health measures are being implemented…and any patient suffering from flu symptoms is being isolated from the others.”

Disbelief and sarcasm in the streets

For some in Syria, coronavirus is still something of a joke. Many simply don't believe what is happening around the world.

“This all reminds me of the days of bird flu and swine flu, and SARS, and so many other names…and they all had no impact on us," Abu Ahmad, a butcher from Latakia, told SyriaUntold, on condition of anonymity.

Abu Ahmad said that he actually believed the virus was a "political game between China and the US.”

“Enough already with this lie!” He added. "We only want to live a normal life.”

Shopkeepers like Abu Ahmad have taken some precautionary measures by wearing gloves and masks, and disinfecting their stores. But the desire for normal life to continue as best it can, especially at a time of economic crisis in Syria, remains.

The cynicism of business owners and ordinary people perhaps only dwindled after the government decided to shut down schools, universities and public spaces, launching street campaigns to disinfect hospitals, schools and roadways. The March 21 circular also ordered closure of markets, services as well as cultural and social activities in public, while another circular the following day suspended work in government ministries and affiliated departments until further notice.

As a result, people reduced their gatherings and started to take precautions, stocking up on food and hoarding as much as possible. In turn, that led prices to shoot up.

These measures are bound to protect people from infection more, but at the same time they overlook a whole group of people living on daily wages.

Rajaa Mohammad (pseudonym), 54, who owns an engineering office in Al-Sheikh Daher area in Lattakia’s commercial centre spoke to SyriaUntold, arguing, “The lockdown aims at avoiding coronavirus infections and potential fatalities. “It's a good step,” said Rajaa Muhammad (not his real name), who runs an engineering practice in Latakia's commercial centre. “But preventing a huge setion of the labour force from working during this period will be a death sentence for their families.”

“People will not comply, whatever the cost," he added.

In a post on his social media page, a Syrian journalist similarly commented on those blaming “ignorant and overly gregarious people” for going out into the streets, saying that “people are well-aware and know the risks, but the viruses of impoverishment, need and starvation came long before [COVID-19].”

“Nobody has the right to blame people whose only choices are to die of hunger or die of [coronavirus]. They have been left with no other alternatives."

That's why the government rushed to impose a quarantine…to avoid a repeat of what we've been seeing in Italy.

Does Syria have the capabilities to combat COVID-19?

Syria's health sector has been hit hard after up to 10 years of war. During that time, dozens of health centres became out of order, and shortages of medical supplies have become a significant problem. US sanctions have only further depleted medical resources. And according to a 2019 study of national health sectors around the world, the Syrian health sector now scores two out of five—five being the best prepared health system—indicating that Syria has only average capacities. These figures go some way to explaining why Damascus rushed to impose a quarantine followed by a curfew, except in the case of essential businesses.

But can the country ward off a pandemic?

One doctor from Tishreen University Hospital, speaking on condition of anonymity, isn't so sure.

“If one case is confirmed, and we have an outbreak, our capacities to deal with [COVID-19] are minimal," she told SyriaUntold, describing shortages in key supplies needed to treat those hospitalised by the virus.

“We have limited oxygen for coronavirus patients. And we don’t have enough ventilators for patients with severe respiratory failure either.”

The doctor suggested that if a major outbreak occurred in Latakia, with high numbers of cases being hospitalised for life-saving treatment, medical professionals would haev to turn to what she calls "war medicine."

“Younger people who are infected would be prioritised over the elderly,” she explained. “So that's why the government rushed to impose a quarantine…to avoid a repeat of what we've been seeing in Italy, for example."

Latakia is now on high alert.

A matter of national security

Given the severity of COVID-19 outbreaks across the region, including in countries neighbouring Syria, as well as the high numbers of refugees and IDPs in Syria, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNOCHA have classified Syria as high risk.

As such, the WHO has offered support to Syria’s Ministry of Health in an attempt at building its capacities to deal with the pandemic. That support has included supplying detection and monitoring devices, training health staff in several provinces, holding workshops to raise awareness and understanding of the risks of pandemic and supplying the necessary tools to detect the coronavirus, alongside lab training campaigns. As a result, Syria can now conduct up to 200 COVID-19 tests to detect coronavirus per day.

Still, there is one question still doing the rounds: if there are coronavirus cases already in Syria, then why is the Syrian government not announcing them? Some cynics suggest that security branches are actually arresting every infected person and killing or hiding them. That rumour is currently being spread about one Dr. Imad Ismail.

Dr. Ismail was the chief of radiology at Qardaha Hospital and was found murdered in his car. Several newspapers, including pro-opposition newspapers, claimed he was assassinated due to recent statements he'd made about coronavirus, in which he reportedly reported the presence of several cases of infection in hospitals in Latakia.

However, Dr. Ismail did not make any statements to traditional or online media outlets, and he was not a public figure. The story reflects Syrians’ struggle with the pandemic on the one hand, and their lack of trust in the government’s statements on the other.

One doctor speaking to SyriaUntold claimed this was misguided. “The Red Cross and international organisations have a strong presence in most areas of Syria, meaning that if somebody wanted to hide infections, there'd be people [from these organisations] looking on."

“Syria will announce the cases, as and when they happen, because it’s not just a matter of an outbreak, it’s a matter of national security,” he added.

A version of this article was originally published in Arabic here.