In his book Notes on the Cinématographe, French director Robert Bresson (1901-1999) says, "The future of cinema belongs to a line of young independent people who will spend their last penny filming their work, without allowing the materialistic routines of the profession to limit them."

The notes written by Bresson summarize a particular and unique vision of cinematography, of its structure and mechanism, and the power of the images inherent in the correlation between the concepts of space and time with the state of the cinematographers themselves, who monitor the process of forming the picture with their artistic perception. That is the broad spectrum of connotations and meanings that film can contain as dense layers, giving cinema its importance in the contemporary era.

Despite the importance of Bresson's observations as a general guide for various people working and interested in the art of cinema, they constitute a distinction in a country like Syria, where cinematography has been the preserve of a single entity, the National Film Organization, created at the end of 1963 as a subsidiary of the Ministry of Culture, as the authorities recognized the importance of cinema and its impact on society, and used it to spread their propaganda and ideology.

The organization became responsible for overseeing production of films and securing their requirements of experts, technicians and studios. The import of foreign films was restricted to the organization as the only entity supervising it. It became directly responsible for censoring films, which led to a gradual decline in commercial films, as the private sector ceased to produce them.

Cinema in the land of the Ba’ath

Some directors associate their experience in the National Film Organization with what can be called the "artistic identity of Syrian cinema,” a period that stretched between the 1970s and 1980s. This identity presented a different visual form, and is represented by a generation of directors who studied cinema abroad and returned to Syria to make their films, which were produced by the National Film Organization. They include Nabil al-Maleh, Mohamed Malas, Samir Zekry, Raymond Boutros, Maher Kido, Riyad Chia and Abdullatif Abdel-Hamid. This was in addition to the important experiences of Arab filmmakers to whom the organization granted the opportunity to produce their films, such as Al-Makhdu’un (“The Deceived”) by Tawfiq Saleh in 1973, Al-Yazerli by Qais al-Zubaidi in 1974 and Kafr Qasim by Burhan Alawiya, also in 1974.

Many film critics point out that the audiences for most of these films—which were screened at international festivals and won some major prizes—were elitists. Yet, in truth, the filmmakers of this wave were concerned with the social and political situation in Syria, and their films approached issues related to the concept of national identity, the setbacks of the Arab situation and the Palestinian cause—with some boldness.

The authorities and their censors realized that filmmakers had a critical view of society and politics, providing an image conflicting with that desired by the Baath Party.

This was demonstrated in the movie Al-Lail (“The Night,” 1992), directed by Mohamed Malas, and in the deconstruction of the relationship between political and familial authority in 1988’s Nujum al-Nahar (“Daytime Stars”), directed by Osama Mohammed. It was also seen in the approach to the hardships faced by marginalized Syrian communities as a result of the regime’s tyranny in the 1974 documentary film "Daily Life in a Syrian Village," by the late Omar Amiralay and Saadallah Wannous.

Symbolism, and the use of allusion and metaphor to represent reality, are all at the heart of cinematic work and the structure of motion pictures. They were also, however, ways for Syrian filmmakers to bypass censorship and examine its consequences, in terms of distrust in the general project of the Ba’ath Party, which had come to power through a revolution that Syrians had hoped would bring a social revival and renaissance. This could be seen in Omar Amiralay’s 1970 film, "An Attempt About the Euphrates Dam," which celebrated the building of the dam on the Euphrates as an achievement of the ruling Ba’ath Party.

The film won the short documentary award at the 1972 Damascus International Youth Film Festival. This encouraged the National Film Organization to produce "Daily Life in a Syrian Village," which was later banned.

The authorities and their censors realized that filmmakers had a critical view of society and politics, providing an image conflicting with that desired by the Ba’ath Party. This led the latter to tighten its control over filmmakers. The organization witnessed divisions and disagreements between filmmakers and the administration, which adopted the stance of the authorities. As a result, directors such as al-Maleh, Malas, and Amiralay stopped working with the organization, though they did not stop making films, and continued with their forward-looking vision of the reality of life in Syria during the decades of Ba’athist rule.

In this context came films such as 2002’s Sunduq al-Dunya, in which Ossama Mohammed further deepened the deconstruction of the relationship between the structure and fragmentation of the family, and the submission to the authority of religious heritage in parallel with political power. As for the 2003 film, "A Flood in Ba'ath Country," Omar Amiralay exposed the fragility of the Party’s slogans. The dreams of a socialist, progressive society are thus shown in utter contradiction with a miserable, backward reality, with pictures of the supreme leader raised over this spiritual and social wreckage.

"In 1970, I was in favor of modernizing my country, Syria, at any cost. Even if the price was to dedicate my first film to praising one of the ruling Baath Party’s achievements, building the Euphrates Dam. Today, I blame myself for what I did.”

This is how Amiralay introduced his last film, "A Flood in Ba'ath Country," which, in reflecting his experience over the course of 33 years, also captured the experiences of his generation of Syrians under the Ba’ath Party’s rule.

Amiralay's experience was a special case among his peers within the world of Syrian cinema, in terms of his commitment to the documentary form, and the shocking and candidly critical view of reality presented by his films, which highlighted marginalized and oppressed individuals and their dialectical relationship with power.

After the revolution

These films influenced a later wave of young filmmakers, who found themselves outside of the governmental organization and its working mechanisms, which were inconsistent with their ambitions. With the emergence of video technology and the possibilities it afforded them to produce films of an independent nature, in terms of production and thought, a new wave of filmmakers was formed in Syria at the start of the new millennium, establishing the concept of independent cinema.

However, the deluge of images that emerged from Syria after the outbreak of the revolution, and the nature of these images (which became a part of the conflict taking place in the country), would have given a new dimension to Robert Bresson’s statement. It would have taken it outside the technical framework and the material condition of the film-making process, towards urgent questions about the role and nature of the image in a time of political and social transformations, and how to approach these transformations by formulating a discourse that favors marginalized people during war, and towards forming an inclusive political awareness.

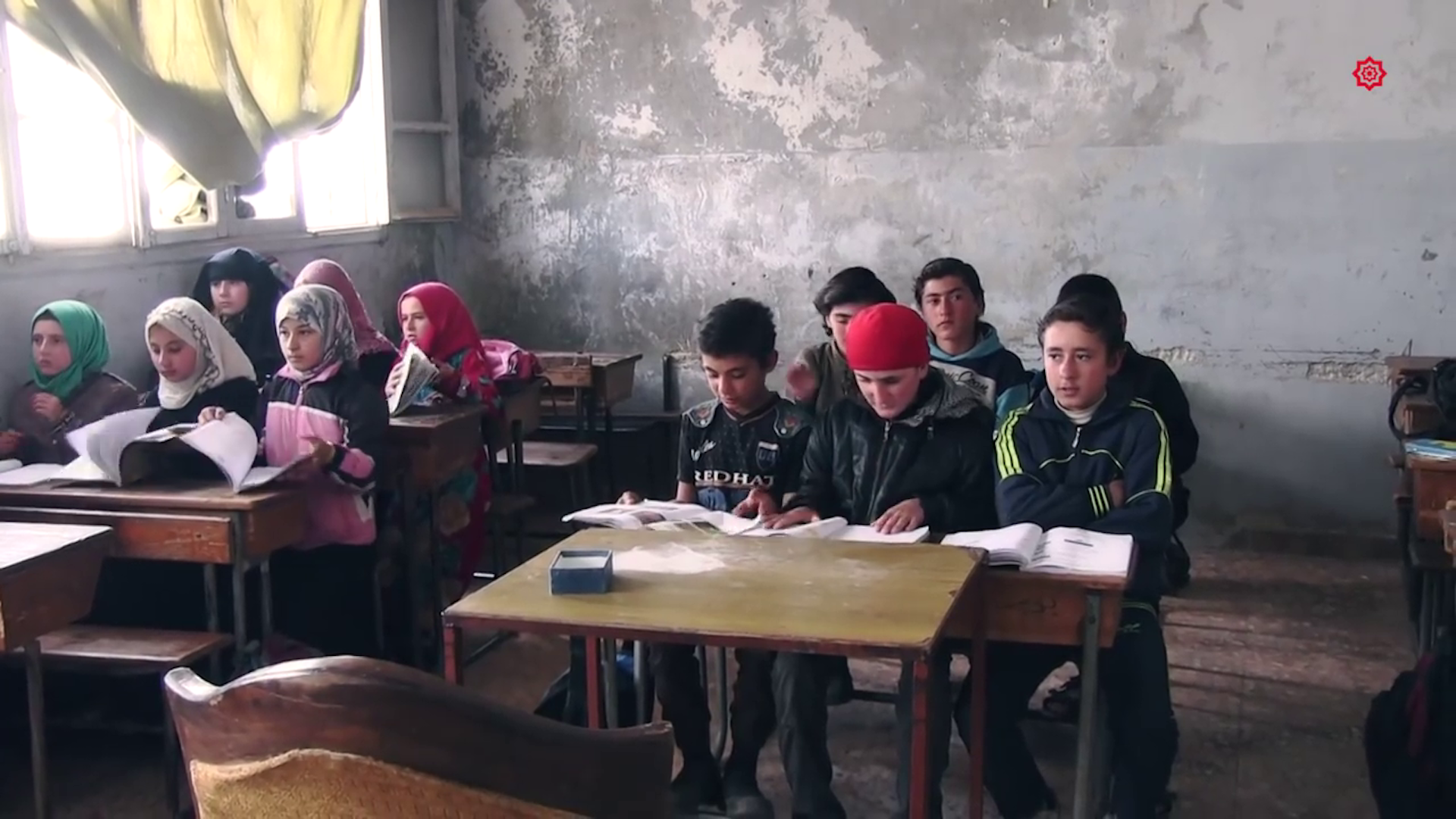

The Syrian film scene post-2011 brought about a radical change in the form of films that appeared after the revolution, in terms of images, and the topics addressed. Without doubt, this change was linked to the essence of the revolutionary movement, through the attempts by protesters and activists to broadcast live images from the streets, despite the difficulties and dangers that ultimately cost many of them their lives.

The beginning of this phase witnessed a particular pattern of videos coming out of the streets of rebellious cities and neighborhoods. Their purpose was limited to transmitting daily events and specifying the locations and slogans of demonstrations, in response to the silence and media lockdown imposed by the regime.

Many of the videos filmed on protesters’ camera-phones were basic and low-resolution, conveying only the event as experienced by the protester-videographer. What distinguished the images was their boldness and spontaneity, and their desperate attempts to affirm the cohesion of the masses in the streets, and the harmonious movements of their bodies, whether swaying in chants, dancing to the melodies of revolutionary anthems, or running away from shots fired by security forces.

It wasn’t long before the need arose to liberate these images from the power of the medium itself too, by combining video clips within stories describing the revolution and uprising in the streets, creating films and narratives aimed at conveying the events.

For its part, the National Film Organization continued to produce films—mostly feature films—that presented a narrative consistent with that of the authorities. Official media also retained its image through the use of professional cameras on tripods, which transmitted images from various Syrian provinces and cities claiming that the situation was stable and the regime was unshaken by the mere protests of a group of infiltrators and rioters.

The act of killing itself was not enough. Rather, to further torture and violate the body, the regime’s method was to eliminate the act of revolution by eliminating its body.

This official image, aimed at portraying the regime’s stability, was accompanied by videos filmed by many civilians who supported the regime, security agencies and the army in suppressing the revolution, which were leaked on social media. Other footage showed demonstrators on the ground with their hands tied, as the shabeeha (regime thugs) rained down feet and rifle butts, and pummelled them. Video clips from detention centers also revealed the torture and humiliation of citizens who’d been arrested during the demonstrations.

The act of killing was itself not enough. Rather, to further torture and violate the body, the regime’s method was to eliminate the act of revolution by eliminating its body.

This situation brought with it contradictions and raised questions about cinema. Should film simply document events in Syria, with scenes from the heart of the war as real-time testimonies of what was unfolding, sketching the features of Syrian tragedy as it truly was? Or should it instead tell a story, narrating what the filmmaker believed was happening?

Image liberated, society divided

With its inception, the revolution brought a liberation of the image from the restrictions of censorious authorities, and became an amalgam of pictures conveying the reality of Syria, and a visual document free from the obligations of the artistic and symbolic form that characterized Syrian film in previous eras. However, this did not prevent some films from being subject to the conditions of the producing entities.

These films sparked controversy about the ethical and technical attitudes to which their creators must adhere in choosing the subject of their film or realizing it. It is something that has long been tackled in cinema when accompanying major worldwide events and changes. However, in the case of Syrian documentaries, it constituted a pattern of opposites and contradictions in and of itself.

The sharp division within Syrian society regarding attitudes towards the revolution has raised questions pertaining to the audiences for whom these films are made, and the platforms available to exhibit them, most of which are confined to international festivals and private screenings.

A distinction can be made between general narratives with which filmmakers attempted to formulate a vision of the revolution, and the later transformations following the outbreak of armed conflict.

In his 2013 film "Return to Homs," director Talal Derki follows the life of Abdel Basit al-Sarout and his metamorphosis from a peaceful protester and leader of chants at the demonstrations, into a fighter in the ranks of the Free Syrian Army—and later certain factions with an Islamist orientation and discourse. The film provides us no insight into these fundamental and fateful transformations, nor their implications on the character of the young al-Sarout, who went from being the star goalkeeper of Al-Karama football club to another form of stardom during the street protests. The film also overlooks the criticisms of al-Sarout by many when military circumstances compelled him to make certain alliances seen as undermining the revolutionary values of freedom, dignity and change that he had previously championed.

The ending of Return to Homs is the moment in which al-Sarout’s tragic story begins: a tragedy coming from this eventuality imposed by the contradictions, difficulties and complications of the situation in Syria.

In the 2016 film by Avo Kaprealian, "Houses Without Doors," self-narration and personal stories take on a central theme. The camera monitors the sense of limbo and siege that the director experiences, along with his family, in the city of Aleppo, specifically in the al-Midan neighborhood. The camera, positioned on the balcony of his home, maintains a safe distance from the street, observing it from afar. The footage captured by Kaprealian evokes the dread, fear and anticipation that pervades the film. This tension does not derive from the reasons mentioned by the father—the necessity of caution during filming, or the fact that the presence of the camera may cause problems for the family—but rather the director’s juxtaposition of the situation of Armenians living in Syria today with the mass slaughter of Armenians in 1915. The scenes addressing this massacre explore these fears of Syria’s reality, opening avenues of Armenian memory and a bitter history full of bloodshed.

Exile, and the sense of distance and powerlessness it invokes, prompted Osama Mohammed to approach the subject through language and image, in his 2014 film "Silvered Water," produced with Wiam Simav Bedirxan. The image, occupied with the high artistic aesthetics that have long characterized Mohammed’s films, recedes in favor of scenes blended with footage captured by Simav in besieged Homs. This synthesis of YouTube clips as an aspect of the filmmaking strips them of their documentary character, turning them instead into a narrative that attempts to understand the reproduction of brutality in the conflict that Syrians received in return for their demands for freedom. The body, rising up to claim its freedom, is the same body captured in the prison, analogous to the place, besieged and destroyed in Homs.

An awareness and a sense of the importance of the image-document in the Syrian tragedy will later liberate it from the necessity that made it a party to the conflict.

In the 2018 film "Still Recording," directed by Ghiath Ayoub and Saeed al-Batal, the latter talks to a group of photographers in the besieged area of Douma about the image being the last line of defense against time. This is a straightforward fact, but it serves the great purpose of images in times of conflict. Any discussion of the aesthetics of the image and its artistic merits is reconsidered when it collides with lived reality at the moment the camera starts recording the events taking place in front of it. No evocations or characters with a dramatic bent, no stage-setting or visual or sound effects. The reality of war and siege pervades everything in this film, as only a small distance separates the lines of fire dividing opposition fighters from regime forces. A Free Syrian Army fighter talks over the radio with a regime army fighter, while the camera records even after the cameraman falls victim to a sniper’s bullet.

This affirmation of the importance of the camera, as a witness to the drama of war, appears in many films as an act of resistance, imposed by the need to narrate the consequences of war on specific groups of people. However, it prevents the birth of a broader view of the larger social transformations taking place in its context.

The 2019 film "For Sama," by Waad al-Kateab, documents five years of revolution in the city of Aleppo. In the film, the camera is a witness to daily life under siege in the city, clearly depicting the tragedy of war and the bombing of civilians in hospitals. However, al-Kateab declares that her testimony is made for her young daughter, Sama, who was born during the siege. Subjectivity is juxtaposed with the general premise, forming multiple paths to explore themes of violence and fear, love and hope, in an attempt to answer the question: When did all this begin? When did Syrians in the revolution choose to continue documenting their own death?

The answers to these questions are not contained within a specific film. However, an awareness and sense of the importance of the image-document in the Syrian tragedy, as an act of resistance against time, will later liberate it from the necessity that made it a party to the conflict.

It will then become a testimony, helping to understand the origins and developments of this years-long conflict in Syria—the most difficult in its history.