On the 10th of August 2013, Syrian authorities arrested leftist activist, journalist and rebel Jihad Muhammad. He has not been heard from since. SyriaUntold, alongside Jihad's friends, comrades and family, demands that Syrian authorities reveal his fate. We also ask the international community and organizations working on the issue of political prisoners and human rights to renew their effort to obtain information about his condition. This piece, part of a series on Jihad's life and activism, was written one year ago in Arabic by Amal al-Salamat, his wife, on the anniversary of his arrest.

The marriage certificate, authenticated by the state’s Shariah courts, the expensive wedding parties, the precious rings. They are not the real guarantee of a sacred union. They are far from representing the joy and love of a man for a woman.

And in fact, Jihad believed he would have remained a completely free man who owned all the world, as long as he registered the house, the car, any other material possessions that he could buy in the future, in my name, his wife's.

From 'You Strangled Us' to 'We Want to Live'

26 June 2020

Secularism in Syria: A national and democratic necessity

13 January 2020

I could only understand the concept of "private property" and Jihad's relationship with it, by referring back to his communism, which he embraced when he was 16, after reading Marx and Engels, and his "foremost inspiration," as he used to say, Hegel.

But on that night of 2012, when children were massacred in Houla, in Homs, Jihad cried desperately. That event stripped him of his communism, of his political universe, of his work as journalist and writer, and of his manhood. He became like "a castrated Syrian male.” That is what he told me after I said to him that “men don’t cry,” my attempt at a joke to ease the weight of his sadness.

I believe Jihad shed tears that day because the sadness really exceeded his body's ability to resist them. I think many other times he cried silently, concealing his tears since the beginning of the “popular movement” in Syria, as he used to call it.

In the beginning of 2011, a skin allergy invaded his body, from head to toe. This was also a sign of the tears he was concealing. Those tears were released in the form of blisters and red spots, which even the doctor attributed to his bad psychological state at that time.

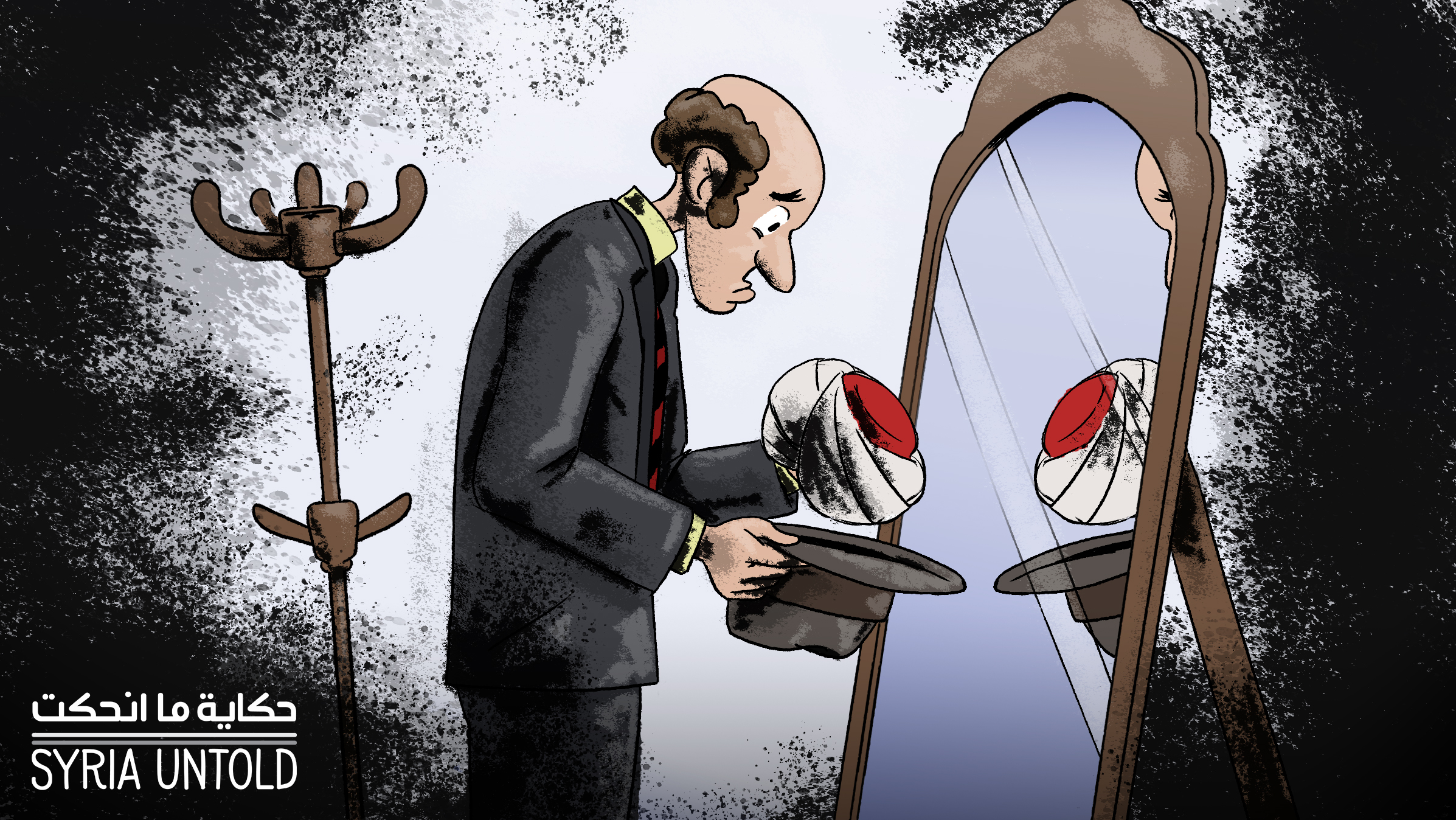

The cause of his maladies can be summarized in a single word: betrayal. Specifically, it was the betrayal from his political current, the People’s Will Party, led by Qadri Jamil and other comrades. All of them lined up in one trench, against the thousands of people who were demonstrating in the streets and the squares of Syrian cities, whom Jihad had joined. He was accused by his comrades of acting haphazardly, of not thinking politically. When Jihad insisted on standing with the rising masses, they accused him of being "sectarian,” and of being drawn back, unconsciously, to his Sunni roots.

Astonished, he told me about this strange accusation. He remained silent for a long period, and then, as usual, when he makes his most important decisions in that silence, he asked me:

“Would you accept it if your salary became our only income?”

“What do you mean?”

“I will leave my job at Kassioun newspaper [a publication of the People’s Will Party].”

“Would that make you feel better?”

“Yes.”

“Then so be it.”

Jihad had given nine years to Kassioun. He used to spend more time there than in the family house, both when he was single and afterwards, when we got married. He began as a simple editor, and climbed up to be the editor-in-chief.

Harasta collapsed under the weight of warplanes and bombs, and we were without home. I sold all my jewelry and borrowed money from family and friends. The idea was to buy a house in Adra al-Amaliyya, a Damascus suburb, through a never-ending mortgage. As we moved in, he said: “The most beautiful thing is that this house is close to East Ghouta.”

In March 2012 he left, after accepting that it was impossible to convince the newspaper's staff that what was happening in Syria was an imperative and historical necessity.

At the time, I sat in on a conversation between Jihad and some of his comrades. They were criticizing the fact that demonstrators were organizing and coming out from the mosques to demonstrate.

He answered: "the demonstrators found in the mosques the only available space to meet. Where else could they gather? In the dusty cultural centers of our country? Or in the imaginary unions, institutions, and organizations? Even if they did, they would have been under the control of security services. If you don’t like it, then why don’t you organize your own demonstrations [away from the mosques]?"

He was standing at a crossroads. He took his decision, and he freed himself, starting his journey on the road of the revolution.

Diving into the revolution

Jihad was not only absent from Kassioun, but also from me. One time I made an appointment with him by phone, and we met in Bab Touma, a neighborhood of Damascus. I was furious with him for being late, but he was happy. That day he had managed to bring a box of blood bags to Douma.

I really don't know if he was listening to me complaining about his long absence from our house in Harasta. I don't know if he was aware to what extent I was anxious and afraid for him, of the danger that the unforgiving security services represented.

In addition to going to demonstrations and being involved in relief work, he was also writing articles in Alef, a magazine, under his real name, about the revolution, for the revolution and for those who identified with it.

On this land, that no one has defeated and no God has ever forsaken, warm hearts will win against cold bullets, eyes will triumph over this momentary darkness, songs and mawwal [a popular genre of vocal music] will win over passing slogans, the wild partridge will win over metallic crows and the clear-eyed soil will overcome blind steel.

Jihad read this to me and asked: "Did you like it?"

It overwhelmed my soul. This was an excerpt from his article "al-Thalj al-Ahmar", the Red Snow. I mention it here because I hope all Syrians will read it.

Nothing but death will drive me from Syria

Jihad became increasingly involved in the revolution. He stopped writing, and during the summer of 2012 refused an offer to work as a screenwriter in Dubai.

I resented him for refusing such a golden opportunity. He told me quietly: "Nothing but death will drive me from Syria.”

I didn't say anything. In that moment I became certain that he was completely dedicated to the revolutionary work on the ground. Any conversation or action had no meaning to him, if they were not made for the sake of the revolution. So I follow him, and I indulged, like him, in that slogan that fueled fire in his heart: “We choose death over humiliation.”

We met one evening at the end of the Summer 2012. He was exhausted, and busy one his phone as usual. He asked me how I was doing. “Very bad,” I answered.

Jihad once survived a stray bullet in Harasta. And he survived, many times, crossing checkpoints. But he did not escape drowning in the sea of the revolution, which prevented him from preserving his life as a husband, as well as his security and his stability.

In fact, as the battles intensified, two weeks earlier, I had had to leave our house in Harasta and move to my family’s home in Damascus. In that period, I was alone, and communicated with Jihad only by phone, because he was perhaps in Ghouta, or in Barzeh. I still don't know exactly where.

We later met in Jaramana. I cried when I saw him. I was angry and told him: “I haven’t seen you for two weeks.” He answered, calm as usual: “You're right. Try to hold on until I am finished networking.”

Jihad wanted the popular movement to be organized and effective. He wanted it to include all those who thought that revolution was an objective fact, rather than an Islamist demand.

The fact that the revolution would be labeled "Islamic" kept him awake at night. He fought with violence, with words and with actions in order to build up a revolutionary group which would include all sides, tendencies and currents against the regime.

I don’t know to what extent he succeeded.

Ghouta is now in Idlib… Who is next?

06 June 2018

But when "S" from Douma swears in the name of the God of Kaaba that he won't rest until Jihad is out of prison, and when "A,” the Marxist, claims that Jihad's arrest was for him a blow to the heart, and when "M,” the Christian, cries over his arrest more than I do, then I understand what Jihad meant when he said he was "networking.” I also understand the level of terror and fear that someone like Jihad could arouse in the regime. Because of this, I agree with "S," "A" and "M" that his arrest was a loss for the revolution.

Harasta collapsed under the weight of warplanes and bombs, and we were without home. I sold all my jewelry and borrowed money from family and friends. The idea was to buy a house in Adra al-Amaliyya, a Damascus suburb, through a never-ending mortgage. As we moved in, he said: “The most beautiful thing is that this house is close to East Ghouta.”

Jihad and his friends began to pay strong attention to the revolution in East Ghouta, specifically Douma. He had a precise opinion on this: Ghouta was the closest pro-opposition area to Damascus, and if the revolution there is able to penetrate the capital, this would accelerate the fall of the regime, ending the raging bloodshed in a shorter time.

A quick victory was important, as he once told me: “I am afraid of fragmentation and regionalism.” At the time, I didn't understand exactly what he meant. Now, after nine years of revolution, I can grasp it completely.

He loved our new house in Adra al-Amaliyya. He expressed to me more than once that he felt safe and peaceful there. I liked that he felt this way. This was, however, in contradiction to how I was feeling, as I entered in that period of deep apprehension for his safety. We knew from friends and from Facebook that Jihad's name was on the lists at the checkpoints and that he was wanted by the security services.

However, he did not care, or at least he pretended not to. He justified his hours and long days of absence from home by saying he didn’t want to take the risk of crossing too many checkpoints.

Clouds of sadness in his eyes

It was five in the evening, in the beginning of June 2013, when he called me and informed me: “I am coming home. I am very tired and I need to rest.”

He looked extremely sad when he entered the house. I asked him why. “It’s nothing,” he answered.

He stayed for 20 days, switching off his phone, taking long walks, and listening, dozens of times, to the "Dice Player," a poem by Mahmoud Darwish.

“How much I resemble the Dice Player,” told me once.

“How so?”

“Here, where Mahmoud Darwish says:

“I survived by chance:

I was smaller than a military target

and bigger than a bee wandering among the flowers on the fence

“And here where he says:

"Fear kept up with me and I continued with it

barefooted, forgetting my little memories

of what I wanted from tomorrow

there is no time for tomorrow

I walk / haste / run / go up / go down /

I scream / bark / howl / call / wail /

I go faster / slower / fall down / slow down / dry /

I walk / fly / see / do not see / stumble /

I become yellow / green / blue /

I split / break into tears /

I get thirsty / tired / hungry /

I fall down / get up / run / forget /

I see / do not see / remember / hear / comprehend /

I rave / hallucinate / mumble / scream /

I cannot /

I groan / become insane / go astray /

I become less / more / fall down / go up / and drop /

I bleed / and I lose consciousness."

Jihad once survived a stray bullet in Harasta. And he survived, many times, crossing checkpoints. But he did not escape drowning in the sea of the revolution, which prevented him from preserving his life as a husband, as well as his security and his stability.

He grew accustomed to the "public duty,” as I used to call it, and he would smile, and then leave. Then I would call our friends, women and men, to let them know whether he was fine and where he was, when he was away for too long and his phone was out of coverage.

'Where should we start the story?'

The 25th of July is my birthday. It is a day Jihad always celebrated, no matter what. He asked me to wait for him in my family's house in Barzeh, so that we can celebrate together.

I had already been there for a week, as my mother's health was very bad. Cancer was taking hold of her body.

I could not figure out the kind of magic that Jihad was able to exert on women. My mother, who used to despise all men, including my father, loved Jihad. She described him as a gentle man, honest and affectionate. She took her last breath on his shoulder, at the end of July 2013.

His eyes held many unsaid words. I asked him what he was thinking. Jihad answered: “Later...when your sadness calms down.”

I could not wait, and I asked him to speak.

“I have to leave Damascus," he said. "I can't stay any longer.”

“Where are you going?”

“To Ghouta, or any other place out of the government’s control. Will you come with me?”

“Wherever you go, I will go.”

“It may be very hard for you with the war, under the bombing.”

“I will manage.”

On the 9th of August 2013, we drew up a plan to leave Damascus, without setting a specific time. There were still some things to be done before leaving. He was sitting, then stood up to make some calls. I felt he was very tall and huge when he stood up. I don't know why in that moment a stream of memories came to me.

Memories of how we met in October 2007, at a hiking trip where Jihad was one of the organizers. At that time, I was fascinated by this man who used to sing, cook and cut logs to prepare a fire.

Then I observed him working in front of a computer at Kassioun newspaper, and asking me to listen together to "A Long American Film," a play by Lebanese composer and playwright Ziad Rahbani, which he knew by heart.

In the evening, when he bid me goodbye, after having travelled a long distance and as we walked through Damascus' alleys and streets, he gave me the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez and told me to read it with love, and to pay special attention to the character of Colonel Aureliano.

Nine months later we got married. I asked him to give me a song as a gift and he decided on "Where Should We Start the Story?" by the Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez.

I keep a small notebook in my pocket, in which I write the dates of the events that changed the course of my life. All dates are written in blue, except for one, set in a frame and written in red.

It says: "Saturday 10/08/2013...Black Saturday, the third day of Eid al-Fitr, between 1 and 2pm, Jihad was arrested".