This article was published with support from The Guardian Foundation and International Media Support (IMS).

A version of this piece was first published in Arabic here.

I have tried repeatedly to describe what I felt the moment I was charged, but I can’t. How sad it is to be a hero in the eyes of foreigners, but mere agents and traitors in the minds of our compatriots, with whom we suffer the same tragedy! Our only mistake is criticizing the politics of a military faction. -Hamza*, 26, Syria Civil Defence rescuer and former Oqab prisoner

Al-Oqab is among the most dangerous prisons in northwestern Syria.

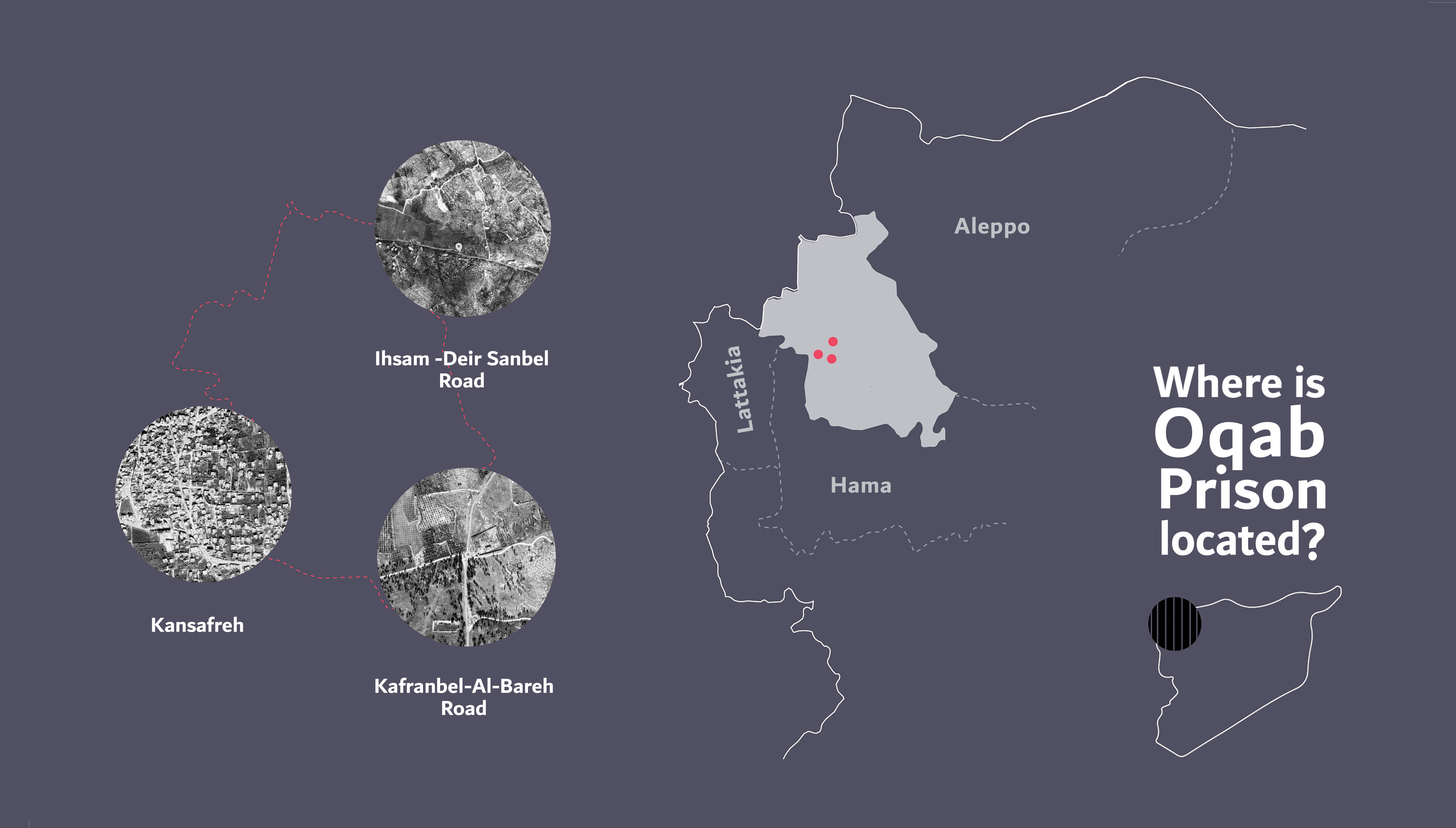

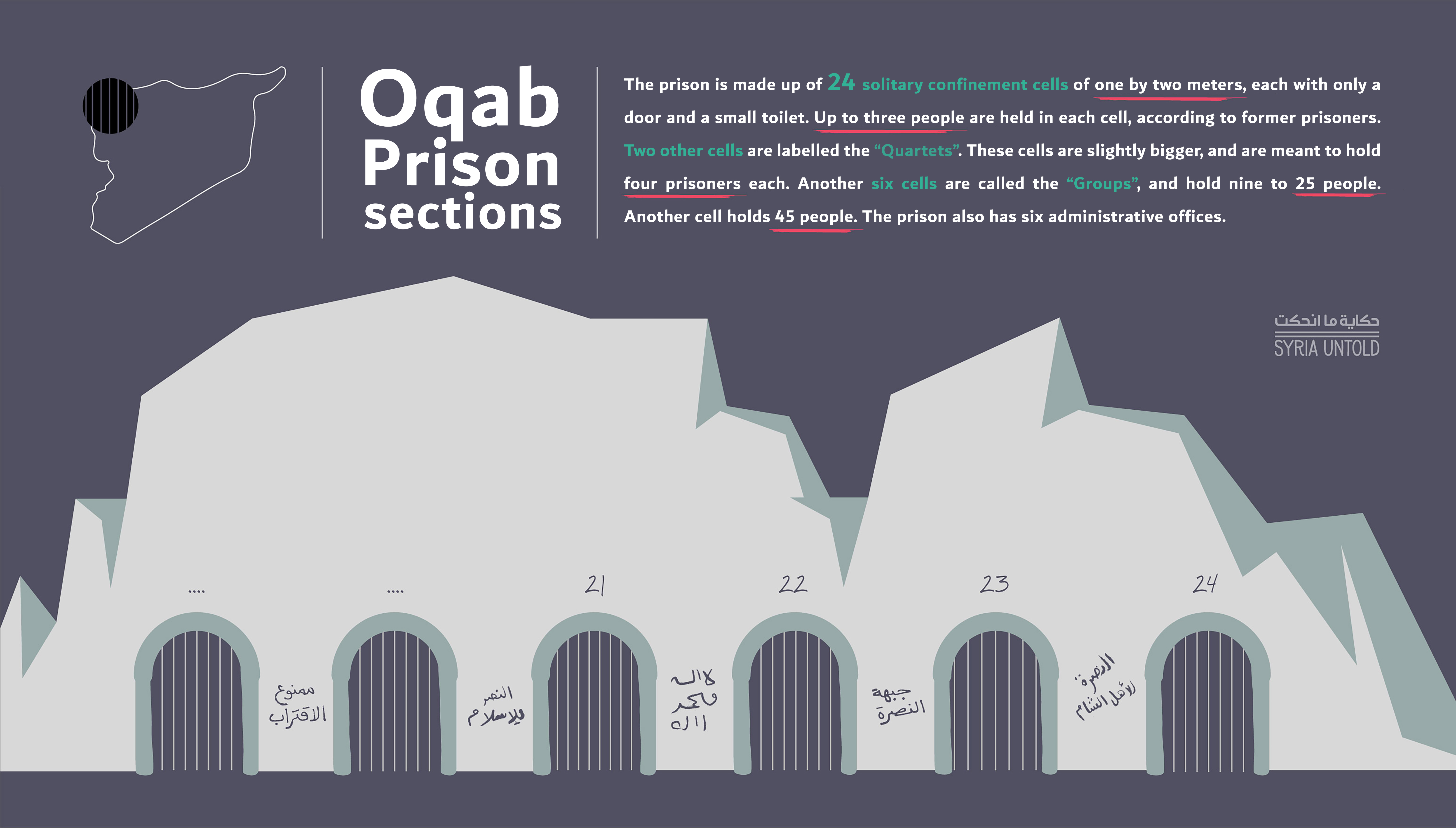

Built partly in a cave, and across 11 poultry farms in a rural, mountainous part of opposition-held Idlib governorate, much of the complex was once intended as a government security facility. But since 2014, when Oqab is said to have been founded, it has served in its current role.

The poultry farmers are now gone; heavy bombing on the area forced them to flee years ago. Only the prison continues to operate. There, detainees charged with speaking out against ruling authorities, as well as other "offenses," languish in poor conditions.

In charge of the prison is Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a hardline Islamist group that holds most of Idlib governorate. And though the usually secretive HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Jolani has appeared in recent months in a number of publicity photos—a possible attempt at improving the group’s image—testimonies gathered from former Oqab prisoners paint a picture of massive human rights abuse by the group.

During my first month of detention in 2018, I suffered breathing difficulties from the high humidity in Oqab, and due to the same air entering the single and quadruple cells through electric ventilator fans. Nobody cared about our health conditions, no matter how far they deteriorated. When a prisoner would pass out, no measures were taken to help, except taking him out to the tashmisa [a sunny corner] for a few minutes before bringing him back to the cell. -Ismail*, 36, former Oqab prisoner

Air vents are virtually non-existent in Oqab, former prisoners said, and any windows in the prison cells are too small to provide much air flow. By the end of week one in the prison, new detainees reportedly begin to suffer skin and breathing ailments. These diseases often worsen due to medical negligence.

Ismail, one former prisoner, recalled skin conditions such as eczema afflicting dozens of people in his vicinity, “especially among those who spent a long time in isolation cells. The toilets in them flood sometimes, forcing prisoners to sit in sewage water on the floor of the cell for days.”

For young Idlib doctors who treated war wounds, COVID an invisible new threat

02 October 2020

“No matter how elaborate I am in my description, and no matter how much you try to visualize the bodies of those infected with skin diseases, you cannot begin to imagine the stench of bodies rotting from humidity.”

Speaking freely, and landing in prison

Hamza believes his time in Oqab was due to a Facebook post.

It was the summer of 2019, and Idlib governorate, particularly the southern countryside, were under intense aerial bombardment by Syrian and Russian forces. The onslaught pushed tens of thousands of people to flee their homes for safety further north, in displacement camps along the border with Turkey.

Those who remained saw their homes, schools, hospitals and local markets bombed to rubble. Hamza, a volunteer rescue worker with the Syria Civil Defence, or White Helmets, was working that summer to save residents who had been injured and caught under the debris in southern Idlib.

It was during one of those rescue missions that Hamza heard HTS fighters had retreated from their positions in nearby rural southern Idlib, allowing pro-government forces to advance.

“While I was working for a whole day and night with other members of our team to pull out people stuck under the debris, I witnessed little support sent by HTS to these fronts, although they had thousands of militants,” Hamza says.

HTS militants retreated all together around 2am, without immediately notifying local medical workers and rescue teams. Nobody knew whether there were more people trapped under the rubble.

Hamza posted about the retreat publicly, on Facebook. He was arrested later that same day, as he passed through a checkpoint run by HTS fighters.

Hamza spent his first month in Oqab prison without any “formal” charge against him by authorities, he says. Those weeks were difficult. He suffered two hours of torture each day: electric shocks, and wooden sticks beaten repeatedly against his fingertips.

Soon, it became clear to Hamza what kinds of people were held in Oqab. Detainees suspected of being on the Syrian army’s side, Islamic State sleeper agents, peaceful activists, media workers who disagreed with HTS’ hardline ideology.

After that first month, Hamza was finally told why he was being held in the prison: for “working against” HTS. The torture continued for another two months, he says, as guards attempted to pull out a confession.

“Nothing you do there can stop the beating,” Hamza says. “Denial only leads to more torture. I mulled over the idea of admitting to the charge, but I was well-aware that confessing would be the death of me...No prayers would save me then. This is the only thing that gave me strength to continue denying the charges,” he remembers.

‘Secular thought’

His hands tied behind his back, Yasser al-Salim, a lawyer, stood before the judge of the so-called Shariah session. He listened to the charge against him: “espousing anti-Shariah secular thought.”

Salim had been a well-known activist in Kafranbel, a town in southern Idlib governorate known for its peaceful anti-government demonstrations and witty protest slogans. He often spoke out in support of religious minority groups in Idlib, including Shia Muslims and Druze.

The work came with its dangers. In 2014, neighbors found an envelope at his door containing three bullets. A letter inside the same envelope warned him to stop his activism.

There’s one demonstration in particular that Salim remembers, his last before prison. It was September 2018, several months after Islamic State fighters launched a surprise attack on Sweida governorate in Syria’s south, kidnapping dozens of Druze women and children, and killing more than 200 people. The slaughter, one of the largest in the course of Syria’s war, was dubbed a massacre.

Salim went out on the streets of Kafranbel with hundreds of others, raising a banner calling for the release of the kidnapped women and girls.

And only a few days earlier, he carried a banner printed in Kurdish, a language banned for decades in Syria’s public sphere: “We stand by our Kurdish compatriots until they obtain their lost rights. What is ours is theirs, and we share the same duties.”

As soon as that September demonstration ended and night fell, security forces affiliated with HTS raided Salim’s house and carried him away.

They drove him to Oqab.

From government prison to Oqab

The prisoners return from the morning and evening investigation sessions jammed in a wagon meant for delivering food. The sessions echo with torture and screams. Some prisoners suffer broken bones in their fingers and in their feet. -Yasser al-Salim, lawyer and former prisoner

In 2011, 43-year-old Abdul Majid* was arrested for the first time.

He had recently participated in an anti-government protest in the town of Maaret al-Numan, in rural southern Idlib. The night of his arrest, though, he had simply gone to a friend’s house in nearby Hass.

Government security personnel raided the house, arresting him and his friends.

He spent the next three months in Idlib governorate’s al-Siyasiyeh prison, which was still held at the time by the Syrian government. He suffered several torture techniques, like “the wheel,” where he was stuffed into a tire and beaten; “the ghost,” in which guards hung him by his hands for long periods of time. Sometimes, he was locked in solitary confinement, he recalls. Other times he was burnt with cigarette butts.

After his release, Abdul Majid joined an armed faction affiliated with the Free Syrian Army. He remained in that position until, five years after his arrest by the Syrian government, fighters from Jabhat al-Nusra—the group that would later form the core of HTS—arrested him. They took him from a car wash station just minutes from the same house where government security personnel arrested him back in 2011.

This time, he was taken to Oqab. But the experience, he says, was eerily similar.

“The torture methods and insults [I experienced] in Oqab mimicked those in the Syrian government’s detention center,” Abdul Majid says. “My body was not spared the whipping, the wheel and the ghost methods for the 14 months I was held in Oqab.”

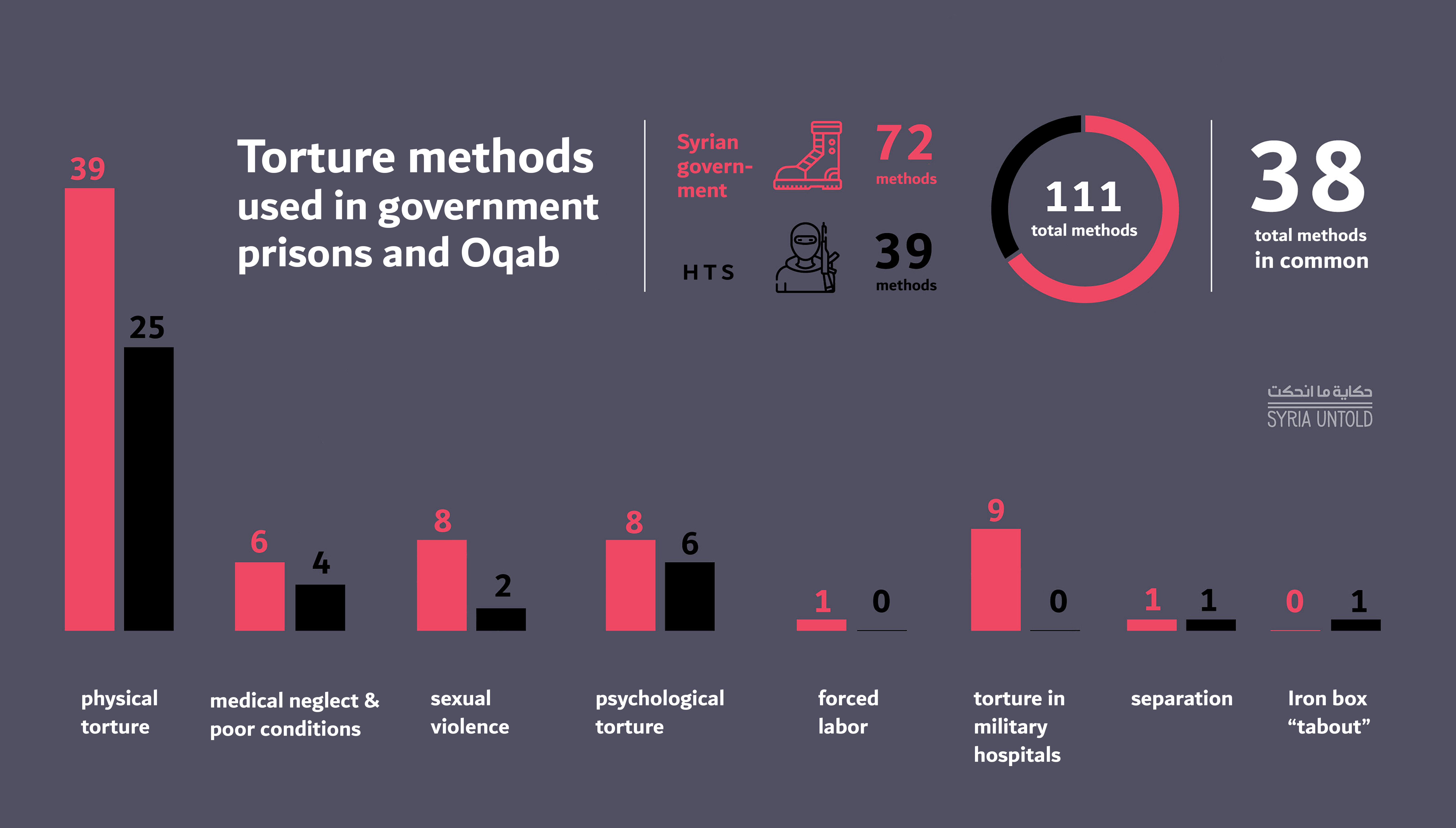

According to a report released last year by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, 38 of the 72 torture techniques documented at Oqab have also been documented at Syrian government detention centers.

Activist Hussam Mahmoud describes similar methods.

Originally from Madaya in rural Damascus, Hussam was forcibly displaced to Idlib in 2017, as part of a deal to end a devastating government-enforced siege on his hometown.

After his arrival, “I was working on a report about the destruction that ravaged the infrastructure in Idlib, including schools, parks and others. The report was part of my work for a local relief organization,” Mahmoud says.

“A few minutes after we started shooting a video, [fighters] raided the location where I was with my friends, and arrested us.” He, too, soon found himself in Oqab.

“I endured various forms of torture on an almost daily basis during the months I spent in prison. The worst were interrogations that lasted about four hours, during which I was beaten with plumbing pipes and whipped with electrical cables. The beating focused on my head and shoulders, to push me to testify against one of my friends in jail who was accused of ‘fornicating’ with a girl.”

“I resisted being weak on a daily basis, and I always tried to do what I could for those asking for my help. But I crumbled in the face of the ghost technique. I was [suspended] next to my friend whose screams I could hear while he was being tortured for about three hours. For a few minutes, I considered confessing to be spared,” Mahmoud says.

Two years after his release, Mahmoud can still feel the effect of the torture he endured while in prison, and is undergoing physiotherapy to treat his neck pain.

Adel*, another former prisoner, says he is also still coping with the physical scars of torture. After two years in Oqab, he is now receiving medical care for injuries to his mouth and throat.

He describes his first few months in the prison as similar to other former prisoners’ experiences. Soon, though, things worsened.

“Five months after my arrest, new torture methods started appearing,” Adel says. “The first method consisted of hanging me from a tackle used in blacksmith workshops. I was suspended upside down during the night hours, usually on the night before the interrogation.”

“During the last year of imprisonment, the easiest torture method for them and the most harmful and harshest for my fellow inmates and I consisted of filling our mouths with salt and leaving it for about 10 minutes, then depriving us of water and food for a whole day. This created a feeling of total dehydration until we felt our throats almost breaking due to the extreme salinity and thirst.”

“During the first months [in Oqab], the beating with electrical cables and wooden sticks was so painful,” recalls Adel. “I thought it was the harshest torture technique one could face in that cave, but I was wrong.”

“I realized later that this was one of the simplest.”

*SyriaUntold has changed the names of some sources at their request, to protect their safety.

This report was edited in Arabic by Hassan Arfa and supervised by Mohammad Dibo.