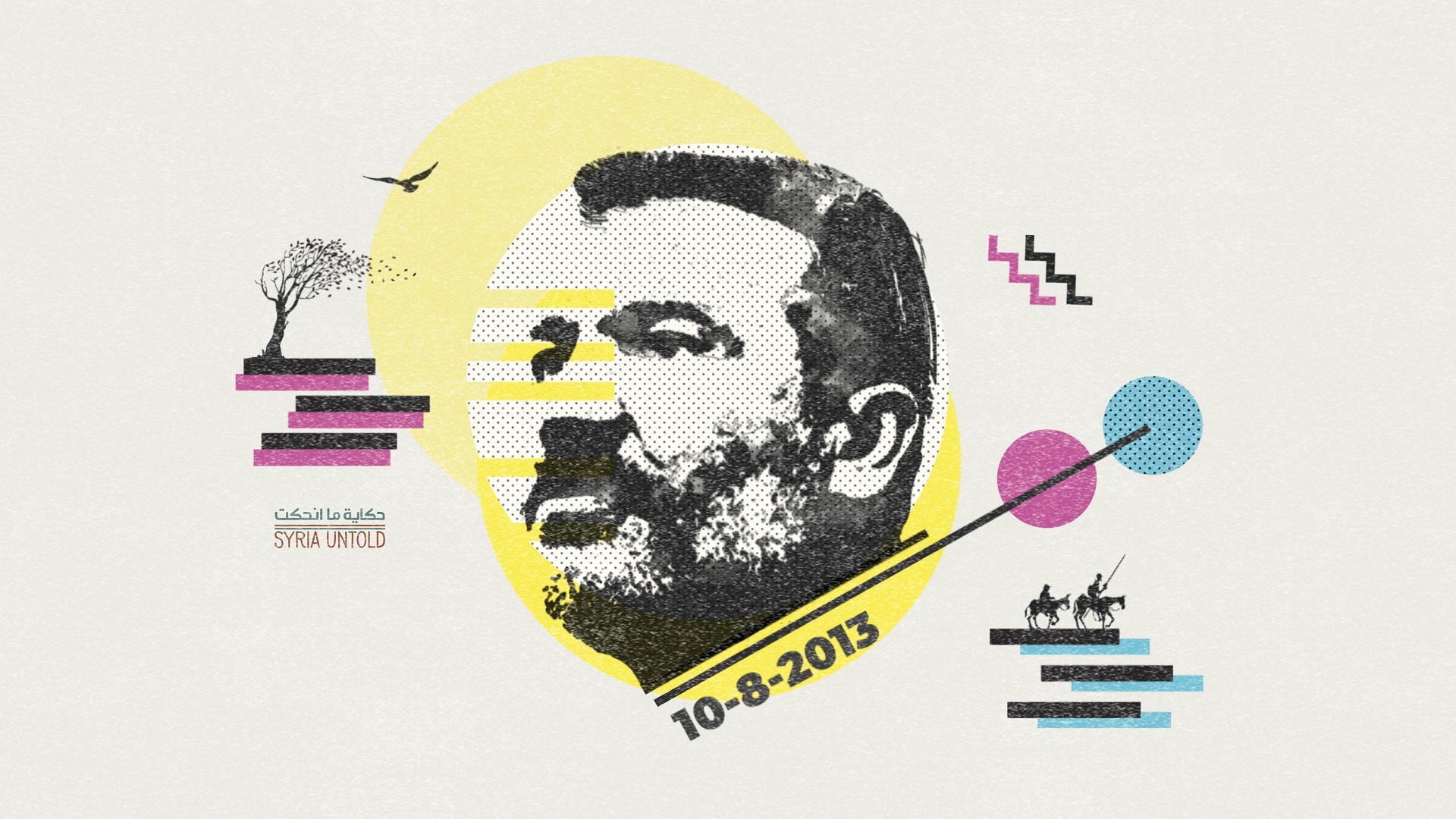

This article is part of a series on Syrian detainees.

“I used to believe that, even if my father was abducted, Raqqa would not keep quiet about it because everybody loved him,”

Hiba Hamed used these words to speak of her father, Ismail Hamed, who was abducted by the Islamic State from Raqqa on November 2, 2013. His absence soon formed a void within each of the family members he left behind.

“I hope and dream that one day, I will return to Syria and reopen his [medical] clinic, which still stands in Raqqa and hasn’t been destroyed,” Hiba says. Now in her mid-twenties, she is Ismail’s second-oldest daughter. After completing her studies in political science in France, she is considering pursuing a medical degree, which she began in Syria, “not out of love for medicine, but to continue my father’s path and reopen his clinic.”

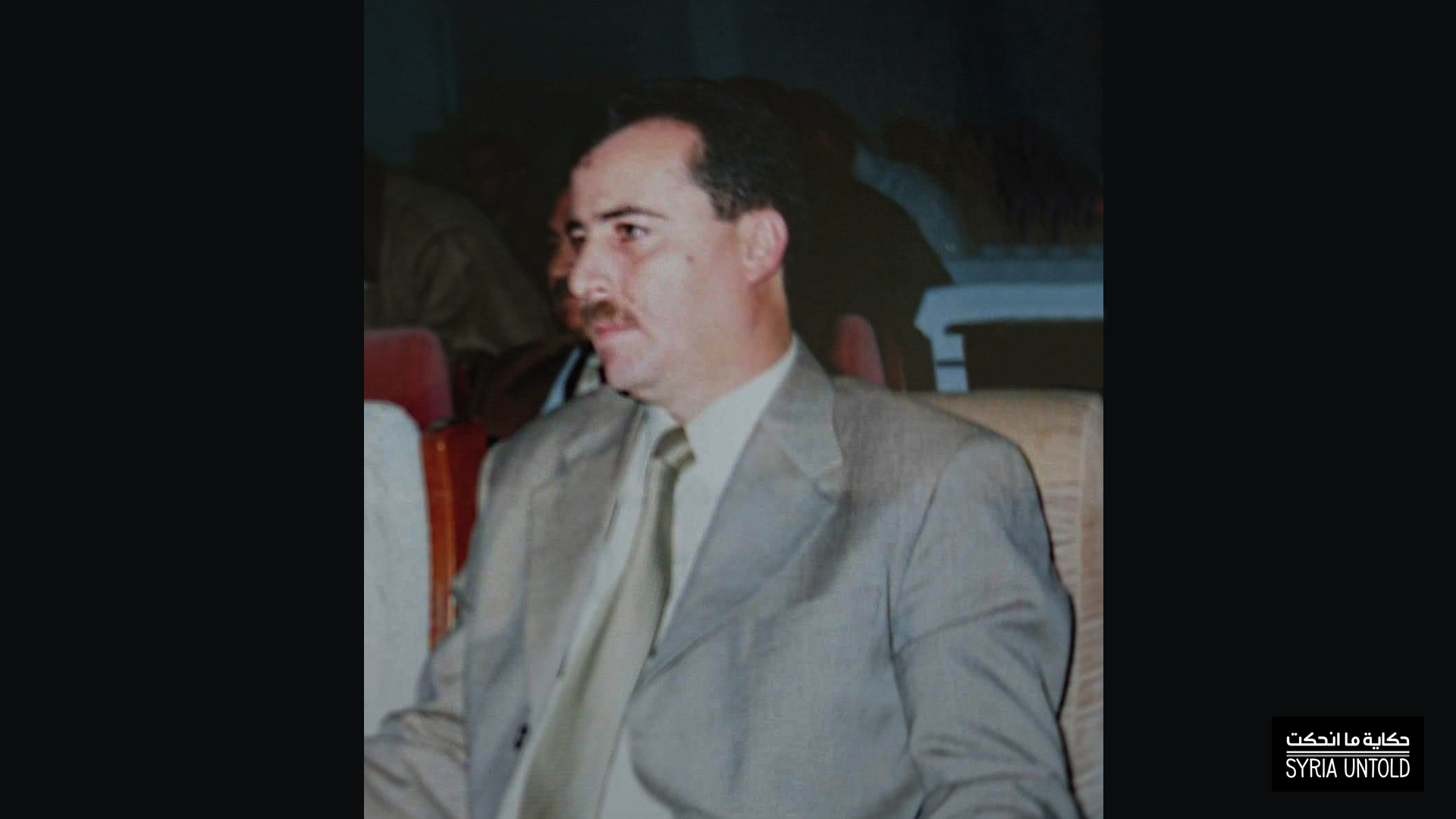

Ismail’s young years were neither easy nor conventional. Born in 1964, he left his somewhat conservative home village, Kafr Nabl in rural Idlib, on a quest for more open experiences that would quench his intellectual, cultural and social thirst.

He studied medicine at the University of Aleppo, and lived in the city for 10 years between 1981 and 1991. Aleppo enriched his intellectual and cultural awareness, which began developing into his rejection of the Assad regime. Ismail shared his opinions with his friends in the opposition, within a narrow cultural circle.

Raqqa, at the center of the universe

16 August 2020

After his wedding in 1990, Ismail opened his own surgical clinic in Raqqa. There, Hiba remembers, he built a special, supportive and loving relationship with his wife and children in a new environment.

“I remember when I was a kid, I used to say that dad was the best doctor in the world. This is how exceptional of a person I considered him to be,” Hiba says.

“My father was loving and caring. He always put his family first. Perhaps all children think this way about their parents, but I believe he is exceptional in the way he chose [to live] his life. Although he comes from a relatively conservative environment, he studied medicine and married my mother, whom he loved dearly, and they moved together to Raqqa. They started their journey filled with love, care and sharing. When my siblings and I were born, he was exceptional in raising us and taking care of us, and he played a main role in that.”

He was driven by his progressive values and defense of the right to be different, to establish “a family that was relatively open-minded for Raqqa, especially at home,” Hiba remembers. “We all had great support from my father in our choices and relations with others. He was not just a father, but a friend, too. I never hesitated to tell him about my life details, even when it was about a relationship with a man. I wasn’t afraid to tell him; on the contrary, I grew more confident after telling him. Perhaps such dynamics in father-daughter relationships do not exist in traditional Syrian families. But my father set the stage for a relationship filled with love, trust and support.”

My mother, keeping us afloat

Ismail’s abduction in 2013 left a mark on the whole family. They supported one other to face his absence. “My mother quickly turned into a strong and powerful woman,” Hiba says. “She was the mother and the father, the source of our strength and the reason for our family’s balance. Despite all the sadness in her heart, she was fighting on two fronts: keeping us safe and discovering his fate.”

My father’s absence also affected my mother, as he had encouraged her, when she was 40 years old, to sit the baccalaureate exam and pursue her university studies. Meanwhile, “he carried the huge burden of raising us so that she could continue studying and fulfil her dreams,” Hiba remembers.

Hiba’s mother and family were resilient in facing Ismail’s absence. But tensions always existed. For Hiba, “what pains me the most, until now, is that my mother had to seek the help of thugs from the Islamic State and beg them for information about my father.”

“I remember how shocking and hurtful it was for me that she had to repeatedly deal with IS thugs, who only cared about humiliating women. We always considered our mother to be a strong, independent and resilient woman. Although she had to deal with bearded thugs to chase and beg for information about my father’s fate, she always fought to keep the family as he had left, loved and known it. She did not allow any space for any family member from my father’s or her side to seep through to practice any kind of authority over us, under any circumstances. We owe her for our survival and safe departure from Syria to France. I am certain my father would be proud of her,” Hiba says.

Looking for someone like my father

Ismail’s children were still growing up when he was taken from them. The eldest, Mary, was 20, while Hiba and Sarah were 19, Rim was 14 and Hazem was 11. They desperately needed him, Hiba remembers, so that they could share their feelings and concerns and ask for his advice.

“Although I am safe, and our family is relatively stable and we have strong bonds, I feel many of my choices as a person are now linked to my father, like my romantic relationships. In my eyes, he is the ideal man. In fact, I find it hard to find the right person, because I am still searching for someone who resembles my father or at least some of his traits. I am sure I will not find anyone like my father,” Hiba says.

“My sister and I were once harassed by a man on the street, and one of our relatives was with us, and of course he defended us. But he was too diplomatic with the harasser. I felt this emptiness, and I immediately remembered a similar situation I had faced in Syria. At the time, when I returned home and my father saw me crying, I told him what happened and he became angry. He went down to the street to search for the man with the traits I described and to bring me justice. I am certain my father wouldn’t have acted violently, but he wouldn’t have been diplomatic either.”

Years later, Ismail’s absence leaves Hiba feeling weak.

“I remember I was stronger, even in the face of IS, because my father was present, and I trusted he would protect me from them. I don’t know how, but this is what I felt.”

Moments of joy, and traces of sadness

Hiba and her siblings have tried to continue their lives normally, as their parents wanted. But sadness always found a way into their happy occasions. It had become a member of the family.

“We felt guilty for leading normal lives” after leaving Syria, Hiba says. “This in itself left us socially and psychologically traumatized. Even after reaching France, I was totally distant from any social or university activity. I felt ashamed of being in a happy setting, and I thought everything should be centered on his absence.”

My childhood friend, now a ghost

18 September 2020

Hiba remembers her sister’s wedding. “It turned into a tragedy even though we tried so hard to be happy. It was not just about the lumps in our throats because my father was not there to share the joy of his first daughter’s wedding. The pain ran deeper, especially for my mother, who was burdened by responsibility. Although the choice of a husband was my sister’s, my mother felt responsible for the wedding and wondered how my father would have acted and what he would have thought of it. This caused her a lot of pain. After my sister had her first daughter, my father was also present among us. The pain did not stem only from not being able to see his first granddaughter, but also from the stories that my mother began telling about the way my father raised us and took care of us when we were kids. She recalled details about our childhood, when my dad was present and protected her.”

Syria’s revolution

Ismail supported the Syrian revolution from the start, and decided to leave Saudi Arabia at its onset in 2011. He had been working there since 2009, and he returned to Syria to join the activists in Raqqa. He was known for his opposition views, which rejected the violent dictatorship. People in Raqqa attested to Ismail’s support for the revolution and the local community before his abduction in 2013.

Hiba believes her father was abducted “because he was an influential figure in the street and a staunch opponent of both the regime and IS. He was not afraid of voicing his opinion on IS, and often expressed his rejection [of the group].”

This took its toll on the Hamed family, which found itself in a position of defense. “What bothers me the most is that those trying to blame my father’s abduction by IS on the revolution, which we supported and adopted, consider that IS was a product of this revolution.”

According to Hiba, “Worse yet, some people even made one choose between IS and the Syrian regime by dragging people into thinking that aligning with the revolution resulted in the abduction of their loved ones. This is really painful, because despite the harshness of all that happened, I always tried to clarify my stance and my animosity toward the Syrian regime, which [is the entity] led us to IS to begin with. The Syrian regime is my main enemy, but it does not negate my hatred for IS. Both are my enemies, but one is savage, and the other wears a tie. It is really tiring to be given only two choices. It is as though our political choices as families are that superficial.”

Still, although she supported and defended the revolution, Hiba says: “Certainly, if I had the choice, at the beginning of the revolution, between saving my dad and rebelling, I would have opted for saving him and leaving Syria, at the risk of sounding selfish.”

Syria is no longer my safe place

“I do not blame the revolution, as an idea, for my father’s abduction. But I do find fault in the people who I think slackened in defending him and trying to discover his fate. I used to believe that, even if my father was abducted, Raqqa would not keep quiet about it because everybody loved him,” Hiba says.

But little has been done to find her father, and this has affected Hiba’s relationship with Syria.

“I was no longer nostalgic for Syria, and I thanked God that we escaped it. Syria is no longer my safe place. My father was abducted there, and we were left alone with fear gnawing at the remaining family members. My relationship with Syria is a complex one, filled with mixed emotions. Sometimes, I hate that place, and I wish we were never there. But, at other times, an undeniable longing for my family gets the best of me. I miss our house and my room more than I miss Raqqa.”

A thousand years older

For Hiba, family has been the main element in alleviating pain and mending wounds.

“We definitely need to cry, break down and be sad. We have so many tears to cry, and during the first months after my father’s abduction, I could not stop crying. The first visit to our house in Raqqa was the hardest, especially upon seeing my mother’s tragic condition. She had lost a lot of weight, her face was pale and her hair was grey. She seemed a thousand years older. But she picked up the pieces and swallowed her bitterness to embrace the family. She held on to life, and so did we. If it weren’t for her strength, we wouldn’t have made it.”

The hope was that, one day, Ismail would return. In the meantime, Hiba makes “small accomplishments that would make my father proud.” She wishes that “father would hear about our latest [news]. I wish he would know how mom succeeded in protecting us and how she acted and the decisions she took, and how we all are fine and are pursuing our studies and continuing our lives. He would then be reassured, and he would no longer worry about us.”

Their pain, once a public cause, became personal and chronic, and only the family members affected by it felt it, each in their own way. They were to be the main bearers of that pain, which may never be healed. Perhaps it will be passed from their generation to the next.

“My father’s absence has opened my eyes to the immense responsibilities, effort and resistance that parents give for the family’s survival,” Hiba says. “Each of us is trying to bear part of the responsibility, and we are investing all our energy to be fine. But, my father’s place will always be empty, and we will keep on waiting for his return to our lives, for him to tell us all that happened to him, and for us to make him proud of all that we’ve achieved.”