This essay is part of a series on shifting narratives in Syrian literature, guest edited by Syrian novelist Rosa Yassin Hassan. Read this essay in Arabic here.

In the past two decades, the Syrian novel has witnessed serious attempts to renew its narrative techniques. In fact, this change in artistic taste, or perhaps in writers’ and recipients’ perspectives on society, might have been a fundamental factor that altered the face of literary production and reception during this period.

Several reasons might have caused this change: the Arab renaissance projects that were cut off and transformed into ideological theorization devoid of content, and the subsequent introversion of the intellectual person after failing to create a reality that matches the level of their ambition. There was also the incarceration of most intellectuals interested in political affairs and partisan work, as well as their escape to work abroad, or their banishment—to say the least—from political work either through intimidation or enticement. Moreover, syndicates and various partisan structures were stripped of their political and social effectiveness. They turned into a facade within a shadow government lacking a plurality of institutions in the interest of a sole security institution that tightened the noose on the judiciary, the economy and the army.

Those were generally indirect reasons. In my view, the direct cause behind the change in Arab taste was the Arab individual’s awareness of themself and their rights, and their awakening to the corruption of the authorities controlling their fate. The Arab individual was also influenced by the image of Western individualism and protective democratic regimes, which reached us through translated literature.

Questions about growing change in Syrian narratives

12 January 2021

Raqqa, at the center of the universe

16 August 2020

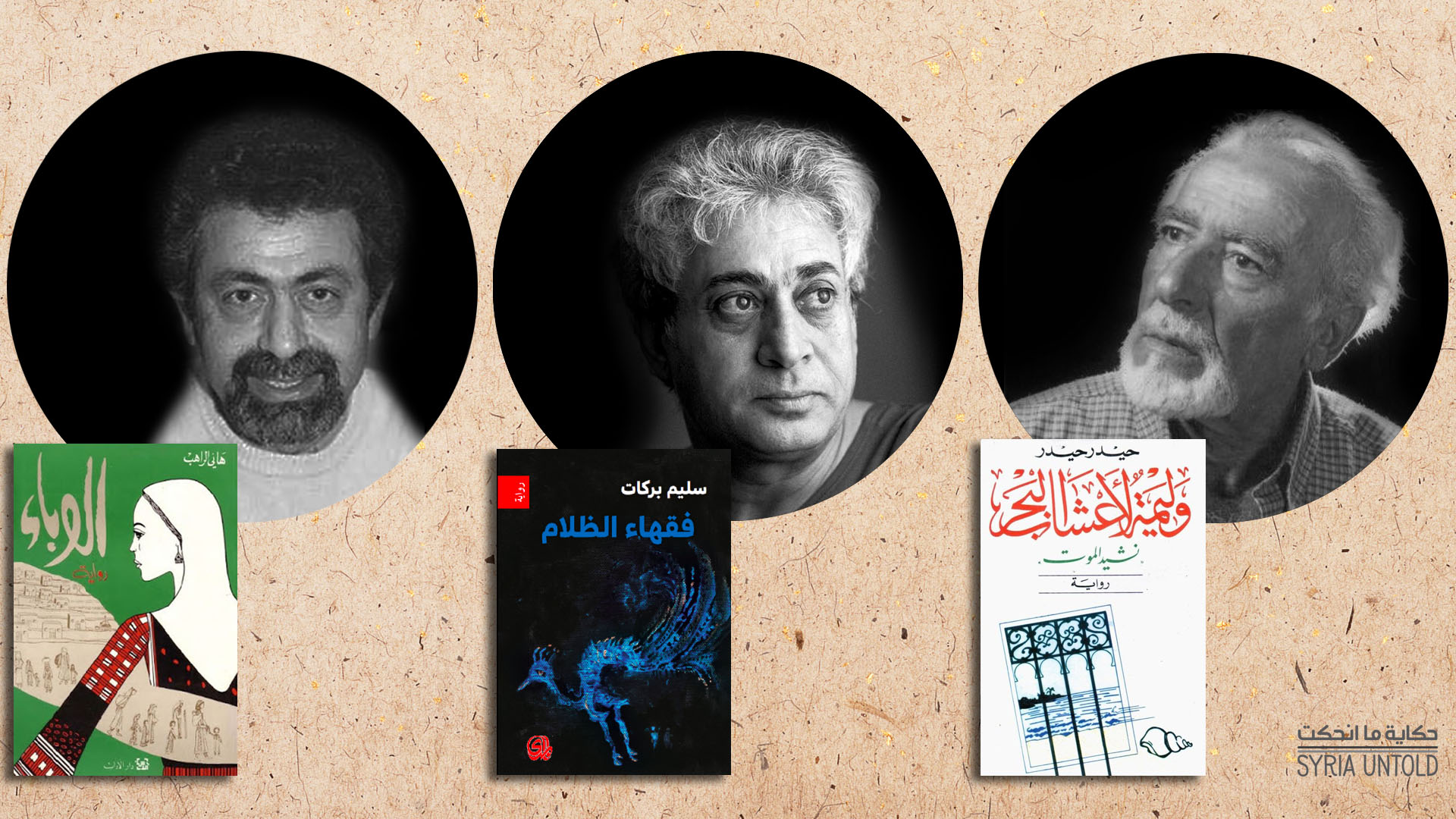

However, the seeds of this change date back to the 1970s and 1980s. Researchers think that its harbingers appeared in the wake of the June 1967 defeat, which deeply shook society. During that period, literary realism controlled the narrative genre in Syria. Consequently, the post-defeat literature, as in the literature of the 1970s and 1980s, continued to be realistic, and it was represented by the pioneers of realism: Hanna Mina, Colette Khoury and Khairi al-Zahabi, among others. But a new trend with clearer features started to form during that stage, and the names of new novelists, like Haidar Haidar, Hani al-Rahib and Salim Barakat, surfaced. These writers did not totally boycott the traditional narrative, which was a real reflection of the experienced reality. But at the same time, they shook the reticence of the narrative world with individual doctrines that sparked a wide debate about their novels.

Perhaps what mainly distinguished the novels of the 1970s and 1980s was the gradual shift from direct realism, presented through familiar techniques, to a novel inspired by reality, albeit while relatively relinquishing its realism in favor of an artistic touch and using techniques considered new to novel-writing at the time, before molding this reality into a novel. Such techniques included dislocation of time and inclusion of excerpts from newspapers in the novel (intertextuality), in addition to asking rhetorical questions.

Notably, the 1967 defeat contributed to distancing the direct political discourse from fiction. It was then that exploration of creative techniques in fiction began. For instance, Hani al-Rahib chose to describe the daily lives of regular people from different perspectives in One Thousand and Two Nights. Meanwhile, in his novels Mirrors of Fire, the Desolate Time and A Banquet for Seaweed, Haidar Haidar delved into the self. He resorted to freezing the notion of time to explore the existential battles raging in the individual’s mind, as well as the psychological conflicts which resonated in the external dysfunction caused by ignorance, backwardness and corruption in both politics and society. A third technique, which Salim Barakat used in The Sages of Darkness, consisted of fantastical wanderings that shed light on the sense of alienation felt by individuals and communities (like Syrian Kurds, for instance) in their homeland or in the countries where they were displaced, in what resembled magical realism. All these novelists shared an interest in the artistic form and narrative techniques to which their predecessors and contemporaries gave little attention. For that reason, critics saw in the novels of that period the start of a new style of novel writing.

Under the influence of the crisis-ridden political, social and economic situation, individualism seeped into the spirit of intellectuals and writers to face the influence of the social power of tradition. Perhaps we are indebted, first and foremost, to this individualism for breaking the prevailing stereotypes and paving the way for spreading novels influenced by existentialism and based on streams of consciousness and psychological time in writing.

Still, despite the existential features that distinguished the first works of some Syrian novelists, they could not escape their designated vanguard role at the time. Consequently, they did not drown in the absurd but continued to mix their personal concerns with general, collective concerns. At the same time, they realized that their real loyalties must not lie with the limitations of fictional work and its preconceived rules, even if that meant risking destabilizing the elements of the fictional structure. In their literature, clear harbingers of new techniques emerged, and their usage was expanded in novels that came later. The signs of the new techniques included:

Fantasy, which infiltrated the novels of that era. Weighed down by defeat and disappointment, the novelist felt this world was not ruled by mind or reason, nor by divine justice. In fact, absolute madness was at the fore, and alliances between major countries prevailed over the interests of marginalized individuals. Those novelists found themselves in Kafka’s shoes, when he felt the state, its laws and control of people killed the human inside them and turned them into insects. Because of these circumstances, the human being turned into a monster devoid of any component of humanity, including his appearance. Although the reasons that led to this transformation differed between our Arab countries and Kafka’s country, the whole Arab situation deformed humanity of its mankind. The change not only affected people, but also turned leaders into monsters, which Haidar Haidar called “Leviathan” in his novel A Banquet for Seaweed. The monster had the shape of a centaur—its upper body a hyena and its lower body resembling a crawling sand crab.

Under the influence of the crisis-ridden political, social and economic situation, individualism seeped into the spirit of intellectuals and writers to face the influence of the social power of tradition.

Salim Barakat chose another form of fantasy in his novel The Sages of Darkness. The novel opens with a calm, logical and coherent narration then opts for dazzling the reader with fantasy, beginning with the birth of a child who grows a whole year in one minute. Afterwards, this strange species multiplies until it forms a whole tribe, unknown to all except through the voices of its people filling the night air while discussing old ancestral properties. Strange events ruled by the fictional logic alone unfold. A sperm turns into a ponderous creature, knowledgeable about the origins of creatures. It recounts, during its journey in the female vagina, its doubts about these origins and its wondering about genesis until reaching the womb. The sperm later begins the process of development until it turns into a full fetus called Bekas who will later constitute the focus of the novel’s fantasy.

Popularity of the stream of consciousness. This element represented a preoccupation with the thoughts in the individual’s mind under the effect of the passage of time. It constituted the first sign of experimentation in its reversal of the typical escalating chronological order, the centrality of events and their logical sequence. Novelists consequently had a wider space to say what they wanted through the implications of thoughts and feelings, without having to adhere to sequential logic. This association may be related to a series of memories, delusions and nightmares. Haidar Haidar adopted this technique in his novel Mirrors of Fire, as did Hani al-Rahib in his novel The Epidemic, in the chapter “Bread and Freedom,” which can be considered an epic, or a long story exploring the life of a family spanning generations, communities or social groups. The Epidemic explored the lives of three generations over a century of time.

Narration of conflicts through their impact on individuals, as the inner life of an individual is a deep reflection of a crisis-ridden society. Revolutionary optimism disappointed the Syrian novelist at this stage and pushed him to re-examine old records, like those a merchant consults after his bankruptcy. In A Banquet for Seaweed, Haidar Haidar re-opened the books of betrayal and violent killings that happened after the so-called Za’im (leader) took the helm in Iraq. He narrated the bloody events, the assassination of communists following divisions within the party and the circumvention of the July Revolution. The narration, however, was not done from an abstract historical perspective. Rather, it was an account of the history of individuals’ feelings during the peak of the decisive crisis in confronting death. Perhaps that narration was not for the purpose of documentation as much as it was an attempt to process what happened and stir questions about the shortfalls and the reasons behind all this devastation. Questions along the lines of “Where was the defect?”; “Why were these people sacrificed?”; “How did they survive all this torture?”; and “Why did an insider betray his party?” were left hanging in the air, without finding conclusive answers in the novel.

Circumventing the familiar narrative time through rapid transitions across different epochs. Time becomes governed by the author’s own vision, where it once was the element controlling the novel. This was among the controversial points in Rahib’s novel One Thousand and Two Nights, starting with its title, which intended to insinuate that the era of One Thousand and One Nights continues to this day; that the one thousand nights of the Sultan’s tyranny, slavery and superstition still control our fates. The prologue indicates that Rahib deliberately mixed the times in the novel to clarify the perpetuation of old times. The novel then highlights the defeat, introducing a new era that does not resemble the preceding one thousand nights. It ends with the time of the novel itself, where the notion of time is overlooked sometimes under the pretext that the characters have no sense or awareness of time and that the ongoing night of defeat is long, thus revealing that we are living one long and endless night. Rahib also used a sort of synchronization in his novel, resembling flashes of composite images in a cinematic film, where shots are captured from different places, but they share one era. This technique allows a focus on the dimensions of daily life in their accurate scenic details that summarize reality with photos here and there, to break down the events and place the scenes in successive, rapid flashes filled with significance. Rahib also narrates images cropped from different places but happening in sync.

*

The number of these attempts within fiction was not sufficient for them to cause significant change. But they paved the way for change, in forms that began appearing in Syrian novels, especially in the 1990s and later on with Samar Yazbek in her novel Salsal, Khalil Sweileh in Writing Love, Fawaz Haddad in The Unfaithful Translator and Ibrahim al-Jabin in Diary of a Damascene Jew, among others. This asserts that modernism in novels is related to the different perceptions of reality and literature and the experimentation boom that is present in all time and space. However, we are now witnessing a rise in the number of novels which have formed their own styles and patterns in writing. The key feature of modern novels or experimental novels remains their specificity and uniqueness in creating techniques and renewing their content.

The above essay is an excerpt from Alhalah's forthcoming book Renewal of Narrative Techniques in Syrian Novels.