Read this conversation in Arabic here.

Nidal al-Dibs, a Syrian filmmaker, was born in Homs in 1960. He studied architecture at Damascus University before traveling to Moscow to study cinema at the prestigious VGIK school, graduating in 1994. He worked afterwards at the National Film Organization in Damascus, and wrote and directed a short fictional film, Ya Lail Ya Ain (1999). He later wrote and directed two feature-length fictional films: Under the Ceiling (2005) and Rodage (2008). He directed the documentary film Hajar Aswad (2006).

In this conversation with fellow filmmaker Eyas al-Mokdad, Dibs speaks about his lifelong relationship with cinema and Syria, his studies in Moscow, the work of Syria’s National Film Organization and the place of cinema in the "room" of Syria’s political sphere.

***

Eyas: You are one of the third generation of Syrian filmmakers, who were given the chance to study cinema in such an established and important film school as the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Russia. However, before diving into this stage, I would like to know more about your personal history.

Nidal: Ah… very well… you want to take me back to my childhood?

Eyas: Let me explain why…

Nidal: I completely get what you meant. Even if you didn’t ask, I would have gone to the same place. Because, in truth, the story of cinema has started there. First things first, I was born in Homs. My family is from Suwayda, but I was born in Homs.

My father was a traffic policeman in that city…he was a farmer before volunteering in what was then called the gendarmerie, [part of the] Ministry of Interior. Because he was able to write and read, and because he knew some French, they hired him as a traffic policeman. He was an exceptionally good, truly kind person…well liked in Homs city.

I grew up in a simple neighborhood, to a large family. Homs at the time was more a village than a city. My memories often get mixed between my life in Homs and the village where I used to spend the summer in Suwayda…many things were common between the two, in particular the landscape. There is basalt in Suwayda, and there is basalt in Homs…so in my mind, things get mixed up sometimes while trying to determine whether a memory occurred here or there.

But what is important for me is that Homs was like a village, visually speaking, and in terms of social relations. My father was well liked because he did not issue a lot of fines against drivers…though in Homs at the time there were no more than 10 or 20 cars, including buses and other means of transportation. We are now talking about the early 1960’s, during my childhood.

My family was poor, not even middle class, despite my father being employed; the family was large, so providing for everyone was not an easy task for him, which is why we used to work. Two days ago, I was telling my daughter Salma about my first ever job, which was paper bag-making. At the time, plastic bags didn’t yet exist, so paper bags were common in fruit and vegetable markets. These paper bags were made at home; there were no factories to manufacture them. My father used to bring us paper cement bags from the workshops, and we would cut and make paper bags out of them at home. The first time I used my hands professionally was to make paper bags…the whole family used to do so. Later, my father’s work was moved to Damascus.

Eyas: Which year?

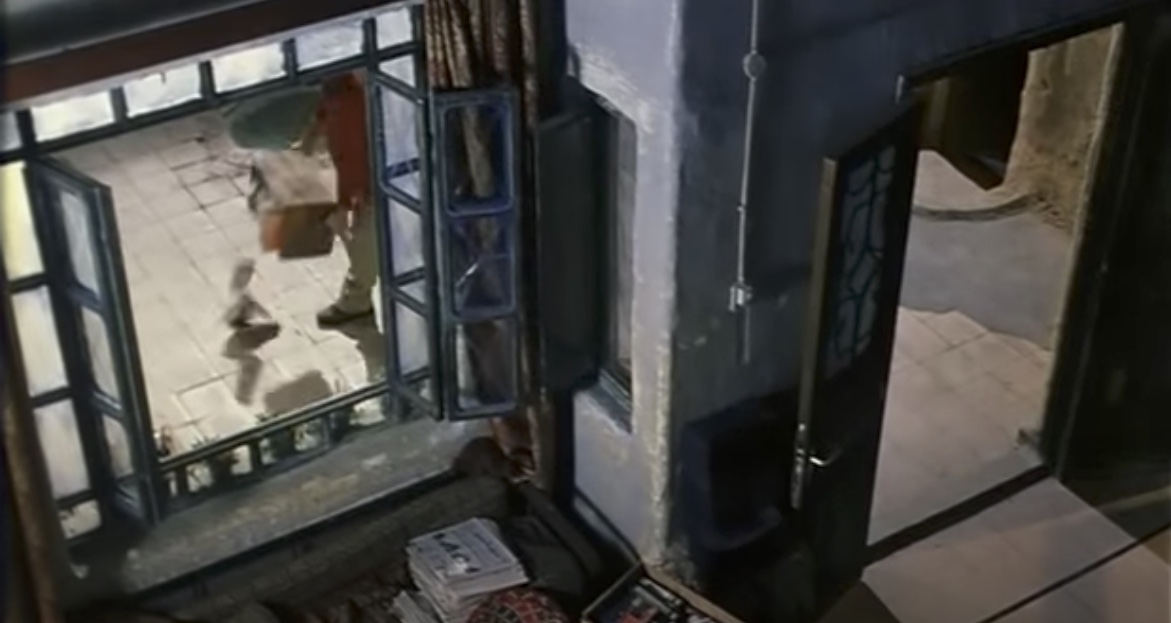

Nidal: This was in 1967, one month after the war. This was the opening statement of Under the Ceiling (2005). The film started like this:

“We moved to this room one month after the 1967 war.”

This was an exceptional event.

Eyas: In Under the Ceiling, the protagonist, Marwan (played by Rami Hanna) moves with his family to Damascus one month after the 1967 war, and the people in the neighborhood think they are displaced, as many people in that period were. Did the same happen to you?

Nidal: Yes, absolutely, that was real, because in that period, displaced people were coming from Quneitra and other places. We lived in Damascus, in the Rukn al-Din district, where displaced people from the Golan Heights resided. Specifically, the area between Rukn al-Din and Masaken Barzeh. The latter was all tents back then. When we were young, we used to go there to watch the tents. At that moment, I think it was that the meeting between myself and the big story happened. I had come from a village—regardless of whether it was Homs or Suwayda—to a large city filled with displaced people. The term “displaced people” stuck to our family...it was not possible to explain to everyone the actual conditions of our move from Homs to Damascus under those circumstances.

I will not spend my life confined into the margin, only to come back after a while and ask for a larger margin. The death of the poet is the death of all things we can deem immortal. The poet is a symbol holding on to memory.

I could call it the first shock if you will. To be taken out of your childhood and your small world, from the fields of anemone, and be abruptly thrust in a new environment to see those tents, inhabited by people, and you start wondering: who are they? Why? How? To then later learn that there is Israel, and that Golan was taken…to learn about politics, etc. All that was concurrent with another event. In that period, and such as the case with each defeat, the search started for someone or some group to take the responsibility of the defeat. Among the rumors that circulated at that time was one claiming that the Druze had sold Golan. Many Damascenes believed that rumor, and because of that, the Druze were not liked in that period. They weren’t liked to begin with, let alone after those rumors. Suddenly, my father gave me instructions to never say that I am from Suwayda. He said: “you are from Homs.”

Television entered our house when I was 15 or 16 years old. So I had no relation with the image, but I listened well to the sound of the image…the tale of hearing the image, would one day become the subject of a film. I had a radio, through which I followed sports matches. Adnan Buzu [a well known Syrian sports commentator] to me was cinema, not just sound. I would listen to him and see the match. I would sit alone, reacting to the match, rooting and screaming and overreacting. All of that was due to the effect of interacting with the radio. I didn’t see the match. Sometimes I would listen to the match from the sound coming from our neighbors’ TV.

There used to be a radio program that aired every Thursday night. The program was a “film.” They would play a film on radio the same way they do matches.

The host would start by saying we are currently in so-and-so hall, and then you would hear the audience. The host would then say: “Today we will watch such-and-such film…” It was often an Egyptian film; not often in fact, it was always an Egyptian film. Host: “The lighting in the hall dims…and the projector starts…” Then he would proceed to read the opening credits. The host would go silent when there was dialogue between characters.

Eyas: The host would describe the mise en scène movement and actions in the film?

Nidal: The host would read the scenario for us:

“He sneaks into her room…” Then the host would go silent to allow us to listen to the other character’s reaction: “The girl screams and runs toward the window.”

Due to my large number of family members, who all slept in one room, I had to put the big radio under my pillow to muffle the sound. This was my first relation with cinema. A fully auditory relation; a completely descriptive relation. The relationship with the radio was the foundation, not of the auditory aspect of my relationship with cinema, but of the visual aspect of it. Through my connection with the radio, I would envision everything except for the sound. I would imagine the face of the sneaking actor, the face of the actress, the way she leapt to the window, etc. I was the director of the film…do you see what I’m saying? I am directing the film. The sound is up to you, and the rest, leave it to me.

Distorting Syria

23 July 2020

From exile in Beirut, cinematic ‘beginnings’

17 July 2020

Eyas: Let us talk a bit about the period between 1967 and 1973, that period that was between two wars. The first war was a crushing defeat, and the result of the second war was the illusion of victory. I do not know in what way your generation looked at those events…what matters to me is your personal experience in this respect.

Nidal: I will tell you now, since it will be in my upcoming films.

For me, 1967 was a scene—a cinematic scene, whose description will be my answer to what the 1967 experience meant to me. I will recount three scenes to you.

Scene one: Me, a child, my pastime then was to play on the rooftop of our traditional Arab-style house, which contained many discarded items (odds and ends). There was a small wooden stool, with a seat made of straw, but the straw was no longer there, so it was just a wooden frame. There was a broken rain gutter that was discarded on that roof. I tied the gutter (or the plastic sewer pipe) to the stool. The gutter had a cone-like shape at its end, so it became like a cannon. I tied a piece of rubber to the leg of the stool and started hurling stones, which would launch from inside the plastic pipe with the help of the rubber strip. I was happy with what I had made. What happened then is that one of the neighbors realized what I was doing on our roof, and he talked to my father, pleading, “for the sake of God, try to hide that toy your son made. The planes might think it’s a real cannon and bomb us.” That was my first relationship with the war. I was asked to take that toy apart and hide its parts.

Scene two: This was a horrifying scene, which convinced me that the neighbors had every right to be scared of my cannon that I had built on the roof. This was when Israel bombed the oil refinery in Homs, which was relatively close to our house. I remember us staying up all night, gazing at the fire that was consuming the refinery. The size of the fire was immense. We were children, and we stayed up till morning looking at that fire without any particular demeanor. The image of that fire was a great visual discovery, though I also noticed the troubled faces around me.

Scene three: The violent, momentous, disaster scene. Some people might not believe this tale. If I hadn’t lived this story, if I had read it in some book, I would have brushed it off as mere exaggerations.

There was a group of Syrian soldiers who had fled from the Golan front when the Israeli offensive happened. They lost their way and couldn’t reach Damascus. They were lost in the mountains and wandered for days until they finally reached Homs. Among this group were two soldiers from Suwayda who did not know anyone in Homs. They asked people if there was anyone who came from Suwayda and lived in Homs, so they sent them to my father, given that he was a well recognized policeman in Homs, and people knew him to be from Suwayda. They came to our house almost one week after the Israeli attack. I remember when they came in. They were in horrible shape. My mother immediately started preparing hot water for the two young men, who started taking off their military uniforms. I went into the room where they took off their clothes and saw the state in which these uniforms were. From the accumulation of dirt and continuous sweating for a whole week in the sweltering heat of June, the fabric was so rigid it could be snapped off. The horrible close-up shot in that scene was when they started taking off their military boots and socks. My father asked me to help him in assisting the two soldiers who were unable to take off those boots. When we tried to take the boot off the foot of one of them, he screamed from pain. The whole neighborhood heard their voices. The second stage was to help them peel off their socks. This part was dreadful because the socks were stuck to the skin. I was helping them to take off the socks and the skin would peel off in the process. Their screaming was horrible that day. That was the image of defeat in June…the horrid smell of clothes and socks, peeled-off skin, men crying and my mother boiling water. That is how I left 1967.

In 1973, it was a different case. First, I had become more aware. Second, I had many relatives in Damascus, one of whom was a cousin who later married my sister. This young man was an officer in the army, a model officer. He appeared on the cover page of the Arab Soldier Magazine. This young man loved poetry. He was the one who taught me how to write poetry, and he would bring books to me. He loved me very much, and he’s one of the people who made an effort to expand the field of my readings. I had a very special relationship with him, and being cousins strengthened that relationship, then he became my brother-in-law. He used to live in a place near our house, and he would bring military plans to his house months before 1973. He had an empty room dedicated to working on those plans. I used to go to help him, and that was my first interaction with military engineering tools. I learned all the symbols marked on those plans: a triangle means a tank, a rectangle indicates buildings, etc.

Who are we? Why are we always behind the camera, while the authority stands in front of it? What if we wanted to turn the camera around? How would our image look? When I presented the film, I told them about the Homsi joke, which says that a Homsi person lost a coin in the dark and went to look for it under the streetlight. I added that the film is an attempt to light the place where we lost the coin. I have cast my light, come see what I have seen.

We worked together. He would ask me to draw a tank in this place or a soldier in that place on the map; he had a map the size of the room fixed on the walls. I was practicing war in that room…living the war, to the point that I later started spending time drawing up military plans. I still have some of those drawings. I was obsessed with that, just like my obsession with cinema.

That game was much like a film.

When the war erupted, there was a celebration. It was a festive event. The whole country was in a celebratory state, because we were able to see what was happening with our own eyes, without the need for media. The war started in Ramadan. At the time of iftar in the evening, we would see the Israeli warplanes in the Damascus sky, and how the missiles would launch from the ground to hit those attacking warplanes. We would see the pilots ejecting with their parachutes to escape the flaming planes. Our neighbor in Rukn al-Din was a military pilot, and whenever he finished an operation over the occupied land—on his way to the base—he would fly low over his house, greeting his wife waiting at home. The whole neighborhood would say, Majeed is back. When hearing the roar of the engines, they would cheer the name of the returning Majeed. That was the atmosphere; we were in a state of euphoria. The first 10 days we were in a euphoria that ended when news reached us that a cousin of mine had died as a martyr in the war. The news was shocking, because a few days later, another cousin followed him…and then the news reached us that my cousin, the brother-in-law whom I loved, had also died a martyr. It was extremely difficult. He had been married for no longer than three months. He was practically still a groom, not to mention the special relationship we had. This made me realize that what was happening was not a game, and I started discovering that what happened wasn’t just the triumph of the first 10 days. Things were starting to turn after that, wreaking havoc along the way.

I had an aunt who lived in Golan in a village called Hader. When the devastation started, and the Israelis began coming in, they were displaced. They came to our house, and they were a large family. All of a sudden, our house became a camp. This started my leaning toward politics.

Eyas: Tell me about the Cinema Club in Damascus.

Nidal: The Cinema Club was founded in 1958. It stopped operating for a long time, but after Omar Amiralay [a Syrian film director] returned from France, and with help from [directors] Haitham Haqqi and Mohammad Malas, they revived the Cinema Club in Damascus. I’m talking now about the early 1970’s—1974, from what I can remember. At that time, I had come to know the Cinema Club. My big brother was the one who took me there the first time. My brother was obsessed with cinema, despite not studying this art. He was studying in France, and upon returning to Damascus, he became acquainted with the young people who had revived the Cinema Club. He introduced me to the club, and I became its youngest member. I got to know the guys: Omar Amiralay, Mohammad Malas, Haitham Haqqi, and others. They liked me very much, given the fact that I was the youngest and represented the new blood the club needed to survive. The Cinema Club became my second home. We are now in 1976-77. I was around 17 years old.

Raqqa, at the center of the universe

16 August 2020

‘What we couldn't see’: Q&A with cinema expert Giona Nazzaro on Syrian filmmaking

13 June 2020

Eyas: Tell me about your cinema studies in the Soviet Union.

Nidal: I received a scholarship to study filmmaking after an extremely fierce and personal intervention from Fawaz al-Sajer, Said Murad, Mohammad Malas and Haitham Haqqi. They formed a delegation and went to meet the cultural officer in the Soviet embassy in Damascus. They told the Soviet official: “Nidal must travel to study cinema,” and they did that under one condition: that I had to study cinematography, not directing. Syria was struggling with a shortage of cinematographers—there were many directors and few cinematographers. I agreed immediately. I told them: “I promise to study cinematography, just help me get the scholarship.” The guys wrote me a petition that was signed by all those who had graduated filmmaking in the Soviet Union, alongside several filmmaking figures, such as Samir Zikra. After that, Fawaz Al-Sajer took the petition personally to the Soviet officials in Damascus, and I got the scholarship, which was to study cinematography. I changed the field of study there in Moscow, much to the disappointment of those who had supported me, who considered it a betrayal of the promise I had made. My answer was that it is true, I betrayed that trust.

In Moscow, there was the start of a new tale. It seems that I am destined to live in places that go through major turns of events. I was in Moscow during the period of perestroika, and there was something taking place on the political scene, something big. There was a debate of whether perestroika was able to save the communist regime in the Soviet Union or not, along with fierce arguments about the evolution of the ideological theories, etc.

Now, after I had learned Russian, I started my study in the film academy. The place was different from the image I had drawn in my mind from the stories of old Syrian students who had been there before me, whom I had met in the Cinema Club in Damascus. The place had many conflicting ideas, and many conflicts in its management structure. There was control over the students’ ways of thinking. I started to feel that the place was restricted. Old, remaining teachers who were still working as part of the teaching staff were violent with us. They had the sense that the threads were starting to slip from between their fingers. For instance, there was a consequential book in Russian about Soviet cinema, translated by Said Murad into Arabic. We all read it. The author of this book was Rostislav Yurenev, who is considered among the great critics and one of the most influential Soviet cinema historians. He was the teacher who taught me the history of Soviet cinema in the academy. This was great for me; I had studied the book in Damascus, and now I was a student for the author of this valuable work.

The first and second lectures with this person were catastrophic. He was an ideologized person in the extreme, exceedingly narrow minded, to the point that I reread his book to discover another impression of him. He would spend a considerable amount of time in his lectures justifying his well-known contribution to banning films in the Soviet Union. He was trying to disavow these actions. It was truly a tragedy. The subject he taught was extremely difficult, and he was very draconian with us. I treated his subject the way I treated the subject of national socialist education, which was part of the curriculum in schools and universities in Syria: any place you feel you don’t know what to say, you just have to write “the leader said,” and then put any sentence after that. This way, you get good marks regardless of whether the leader had said that sentence or not.

Yurenev would ask me to analyze a scene in a Soviet film, and I would start by saying, “this scene in the film embodies the Leninist theory stating blah-blah, etc.” This would make him ecstatic, to the point he wouldn’t allow me to continue and he moved on to another student or another question. After that period, the real collapse of the Soviet Union started, which is something I lived through.

My situation in that academy was not the same as other Syrian students who had graduated before me from the same institute. If you asked Ossama Mohammed the same question, he would go on for at least an hour about his close relationship with his supervisor in his years of study, and about the effect Igor Talankin had on his cinematic conscience. Talankin was supposed to be my supervisor as well, but at the last moment, the administration decided to change him without expressing the reason, but I understood why. Talankin was an intellectually open-minded person, and it was possible that he did not support the political changes in the Soviet Union, so he did not teach me. They brought us another supervisor named Marlen Khutsiev, who is considered among the greats in the history of Soviet filmmaking from the 1960’s. We were very happy with the new teacher, but after the first and second lectures, we were utterly disappointed—he, also, was rotten.

This was the main difference between me and the graduates who had come before me. I did not have a supervisor who I trusted to have an impact on me. During the years I studied, three teachers supervised us—they changed teachers promptly and constantly. Assigning teachers was dependent on their political stance towards the measures taken in the higher authority circles, as well as the shift in the center of power within that authority. [We had] three supervisors, none of them like the others, including the Chilean director Sebastián Alarcón, who directed the film Night Over Chile—that great film, if you are familiar with it. He escaped Chile after the coup d’état there to marry a Russian woman and move to the Soviet Union, where he made the aforementioned great film. He taught me for a year. He, too, was a "Guevaran" in the fanatic Soviet way.

I did not have a supervisor, but I exchanged the supervisor with something else.

The solution lies in emptying the room, and you have to start with the books, to start with the theoretical, the fixed ideological. The characters in the film are searching for the sound of their lost steps in the heart of that great city of Damascus, in which old roads are still paved with cobblestone, but there is no sound to our steps.

Here’s the tale: When the Soviet Union collapsed, the stockpiles of banned films were released in Moscow, which was a huge number of films. All the films that were made in the Soviet Union and banned from viewing were kept in storage rooms in the studios that produced them. One such studio was Gorky, which was close to us. When those storage rooms were opened, people flocked to them eagerly. They knew the titles of those films, but they hadn’t watched them before. This allowed me to watch a massive number of banned Soviet films. We were also able to watch the original copies of the films that had been cut by the government watchdog. We were able to watch the director’s cuts of those films, and watch them as they were originally made, not as the authorities wanted them to be. For instance, Tarkovsky’s films that he made in the Soviet Union; these films were not known in their original production as made by Tarkovsky, but in the production that the film authority approved at the time. We watched Andrei Rublev the way Tarkovsky had made it, and saw the difference between the version we knew and this new version before us. We went into analyzing the reasons behind leaving out a certain piece and inserting another in its stead. I was lucky.

Eyas: So, we could say that you learned filmmaking from banned films?

Nidal: Nearly…it was a very vital fountain of knowledge. After we had learned all the classics and essentials of the Soviet school of filmmaking—which is genuinely a great school—in the first and second years, we were given the opportunity to see something completely different. This was a great thing, and I still consider myself lucky. We used to discuss the most minute details in those films. We then had the opportunity to meet special figures. For example, we sat with the sound engineer Inna Zelentsova, who had worked on Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev. He told us about the sound of the church bell in that film, and how they had recorded a vast number of church bell sounds from different places throughout the Soviet Union and presented them to the director to choose from, and how Tarkovsky selected two specific sounds and mixed them together for the film. Henceforth, we started learning in a different manner; we realized that banning is not limited to deleting scenes from a film or banning it altogether. The issue was related to the struggle of those directors and their intellectual and artistic visions. Once, I was sitting next to one of the windows in the academy, when one of the teachers was passing by, and he asked me, “do you want to commit suicide?” The question took me by surprise, and I replied, “sorry, why would I commit suicide?”. The teacher laughed and told me, “don’t you know that Tarkovsky attempted suicide from this very same window?"

The changes were acute. When I was in the first or second year, I directed a scene from a script by Chekhov. I turned the serious scene into a comic one. I wanted to do that, but they wouldn’t allow us to present the scene as such, because at the time Chekhov was treated as sacred, and his literature was not to be tampered with. But after those rapid changes, I was able to present the scene just as I wanted (circus).

Eyas: Tell me about your work with Ossama Muhammad, who would later cooperate with you on your film, Under the Ceiling.

Nidal: With Ossama it wasn’t just an acquaintance on a personal level—what’s more important is that it was on an artistic level, and even on a political level. At that time, there was the crisis of the National Film Organization, which was on its way toward privatization. Filmmakers stood in the face of this project through statements and meetings. In short, we made a fuss, and making a fuss at the time was a political act. We presented our position from the angle that the state is responsible under the constitution to support the arts and culture, and whoever wishes to produce a private-sector film is free to do so. The regime bears the responsibility of striking private filmmaking and ending it in Syria, not filmmakers. We weren’t defending the National Film Organization—rather we were rejecting the state’s abandonment of its role in supporting arts and culture, and we were talking about the mechanisms that must be utilized in order to preserve that role.

I got to know Ossama through working on his own film Sacrifices in 2002. I went to him and said that I was unemployed, and that I’m not asking anything, except for my wish to live this experience. Indeed, I started attending meetings as a listener and spectator only, but after a short time, I started taking part in the discussions, and sometimes they would ask my opinion. After that, Ossama said to me: you should be on the film’s team, and you have to get paid. And so it was; I dedicated myself to the project.

After Ya Leil Ya Ein (1999) I became closer with Osama, and the dialogue started between us. His trust in me increased, and that’s what prompted him to think that I might be useful for the film. He started involving me more in the discussion and in working on the film. This would go on until the late hours of night.

Eyas: Can you describe Ossama Muhammad as a filmmaker?

Nidal: Ossama treats filmmaking as a religion, in a religious, faithful sense. He is one of the Sufis who give their bodies, after the soul, to the project. And that is why I always talk about his work as a project, something more than film. Ossama gives everything he’s got, and drags you in with him, he infects you, and you find yourself entangled as well. You might not agree to give yourself to filmmaking, but his dedication pulls you in.

Eyas: Your first feature film was Under the Ceiling [2005]. Can you talk about this film?

Nidal: Yes, it is torment—the torment coming from that cube-shaped room that has a roof. You are trapped within that room that represents your memory, and all your personal story. It is all you have, your world. Your world is not small; it has diversity, and to a great extent, we can consider it to be expansive. But after that, it starts shrinking, and that cube becomes your limited space. You are out of options. You have no choice but to collude with the roof, with memory. The roof chooses for you what you must see now, which memories will overtake you at every moment! The roof and the television, those represent a modern shape of memory. You find yourself before that challenge. Will you remain inside the cube? Or will you get out of it? There is no other option.

In search of the best picture in the world

22 January 2021

Murder, and the burden of proof

06 January 2021

The other thing is in the form of a question: is the cube fixable? The film protagonist might have been able to fix the room where he lived, but the problem is in the larger cube, or as I dubbed it, the second roof. In each cube outside the first one is a story, and if you keep progressing, toward the street, you will find more cubes and more stories. The idea is not in rehabilitation; it lies in searching for one’s self. Before thinking about repairing or tearing down, you must find yourself, and you need to be clear in your choices, and to not waver. That flippancy in the attitude of the filmmakers and intellectuals that I witnessed when I returned from Moscow to Syria; they were saying that the margin [left behind to them by the regime’s censorship] was enough. No, it isn’t enough.

I will not spend my life confined into the margin, only to come back after a while and ask for a larger margin. The death of the poet is the death of all things we can deem immortal. The poet is a symbol holding on to memory.

The size of the changes that happened—and, here, I am talking about the film—is big. Those young people who would gather to sing the songs of Sheikh Imam are now somewhere else. The protagonist is somewhere else, too. In the film, I was talking about the change in those characters—the conditions they lived in on the margin of life in Damascus. That was my impression when I came back from Moscow. We are trying to belong to a world that might be different from us, might not be similar to the self we have. That was the question before [characters] Lina (played by Sulafa Memar) and Marwan (played by Rami Hanna). The question was: is it possible to recover that memory? They were not able to recover that memory, despite all attempts.

Eyas: In Under the Ceiling, I noticed your criticism of the image of the symbolic fighter-intellectual (shown in the character of the poet, played by Fares al-Helou): that fragile, and sometimes naïve, image; that character who holds no political depth and has no vision. Merely an emotional, demagogic state.

Nidal: Exactly, it is a gregarious association if you want. We must have the courage to acknowledge that. The situation was indeed like this. Poetry created an unfulfilled dream to Lina. When she complained to Marwan, his answer was that the big things made them overlook the small things. Lina is hit with a wave of anger because Marwan called those “small things,” and she blames him for the term. The whole problem lies in considering ourselves small and marginal things, and that what’s more important is to work on big issues, and thus was our loss. True, he is a poet, but he is weak.

Eyas: After founding the National Film Organization in 1963, most of what the organization produced was preoccupied with big issues.

Nidal: Add to that that it was busy analyzing the structure of authority, while I proposed analyzing the person’s own structure: who are we? Why are we always behind the camera, while the authority stands in front of it? What if we wanted to turn the camera around? How would our image look? When I presented the film, I told them about the Homsi joke, which says that a Homsi person lost a coin in the dark and went to look for it under the streetlight. I added that the film is an attempt to light the place where we lost the coin. I have cast my light, come see what I have seen.

In Syrian filmmaking, there was no separation between generations of filmmakers; each generation would hand over to the next generation, and then the new generation would start working on the same ideas with simple additions. We are very respectful of the founders’ efforts, and there was no wish to stray from their traditions. No one came to say, that’s enough, let’s move in a different direction. The country was changing, and the consumer was changing, while the cinema was still inside the cube. The differences between me and my grandfather and my father and the generation that came after us were depicted as very little, which is neither true nor realistic. When Marwan in Under the Ceiling asks his mother to tell him about his early childhood, she replies by saying: “the day you were born, there was a coup d’état, and a curfew in the streets.” Marwan responds by saying: “please, tell me about the color of my eyes, about the scent of my skin!” These are realistic stories; when my father was born, there was a revolution; I know nothing about who against whom it was. Will we keep doing things the same way? Where is the personal that belongs to me? Where is my self?

The protagonist’s finding himself made him capable of acting. He had been unable to have sex, but as soon as he started noticing his inner self, he regained his ability to enjoy life and do what he was unable to do. There was a distortion of the self, and not only because of the distortion that was practiced on us. We also bear part of the responsibility for those distortions.

Eyas: It’s as if Under the Ceiling invites us to look upon the past from our current standpoint, so that we can always understand and accept it.

Nidal: Exactly, and this starts in the film when Marwan decides to empty the room. The solution lies in emptying the room, and you have to start with the books, to start with the theoretical, the fixed ideological. The characters in the film are searching for the sound of their lost steps in the heart of that great city of Damascus, in which old roads are still paved with cobblestone, but there is no sound to our steps.

Eyas: Was the film banned?

Nidal: No, not really. No order was made to ban it, but it didn’t have commercial viewing in cinemas. The opinion was: let’s not give ourselves a headache.

Eyas: Tell me about your impression of the Syrian revolution, with you having been a refugee in Cairo for years due to your political and moral stance.

Nidal: I have said in my films that there is no place for change inside the cube and under the ceiling. That is an unfixable place. That moment in 2011 to me represents that scene in Under the Ceiling when Marwan starts throwing his personal belongings in the yard under the rainy sky. We worked hard in that scene to come up with sounds for the things Marwan was throwing, sounds similar to the sounds of explosions. I cannot say I had predicted what happened, but I can claim that I had called for it, because I believed that the room was unfixable. In the story of the room in Under the Ceiling, if you noticed, the owner of the house where Marwan lived decided to use the rooftop of the room and turned it into a small vegetable patch, which caused water to seep through the roof. The owner is sitting on top of you and the roof will keep letting water through, so the axiomatic solution is to tear it down completely. Do you know that all the posters that were hung on the room walls were my personal collection that I have collected over years?

[During his years working at the Cinema Club in Damascus, al-Dibs collected a number of posters. Those posters were later destroyed during the shooting of Under the Ceiling, due to direct water exposure.]

The original poster of [Syrian artist] Youssef Abdelke’s first exhibition, posters of major international films that were sent to me from France. I wanted to execute all that heritage in the film, looking forward to a new start.

What happened in 2011 was caused by the feeling deep down among Syrians that it was no longer possible to fix this room, and that was what happened.

Eyas: When you talk about Syrian cinema, do you say that there are Syrian films, or a Syrian cinema with defined characteristics?

Nidal: Yes, there is something we can call Syrian cinema. It’s not about quantity, it’s about quality. If there had been only three films, I would have said it is Syrian cinema. Is there a Syrian cinematic language? Yes, there is a Syrian cinematic language. Is the Syrian film different from the Egyptian film, or the Tunisian, or the Iraqi? Yes, it is. Can we discern the Syrian film only through the image without the sound? Yes, and this is not only my opinion; it is the opinion of critics and audiences alike.

Here in Cairo when I meet students or someone who is interested, and I show them Syrian productions, they say: “Ah, wonderful, this is the first time I see the Syrian cinema, not Syrian films.” The audience feels the cinematic language, and the uniqueness of the staff and the shots; the logic of events and story construction. And I am not talking here from the angle of which cinema is the best in terms of value—I’m only emphasizing the idea that there is something exclusive to the films that were made in Syria that makes it have a special language. That cinema that was founded since the production of [Syrian screenwriter and director] Qais al-Zubaidi’s al-Yazerli—even the films that were made in recent years—they have something new and different, but they still have a Syrian flavor. When the start is, as we know, at the birth of modern Syrian cinema, it stands to reason that the cinema would be in the place we see it in today: committed to seeking the truth and standing in the face of tyranny, while at the same time preserving the right of the new generation of Syrian filmmakers and new Syrian cinema to be different from our generation and the generations of Syrian directors who preceded us. A Syrian cinema with ideological constants was founded, but the cinematic language doesn’t have to be stationary, but rather changing and lively. What brings the Syrian directors together, from all generations, is the deep sense of commitment, which turns the project of each film made by a Syrian filmmaker into a life project.