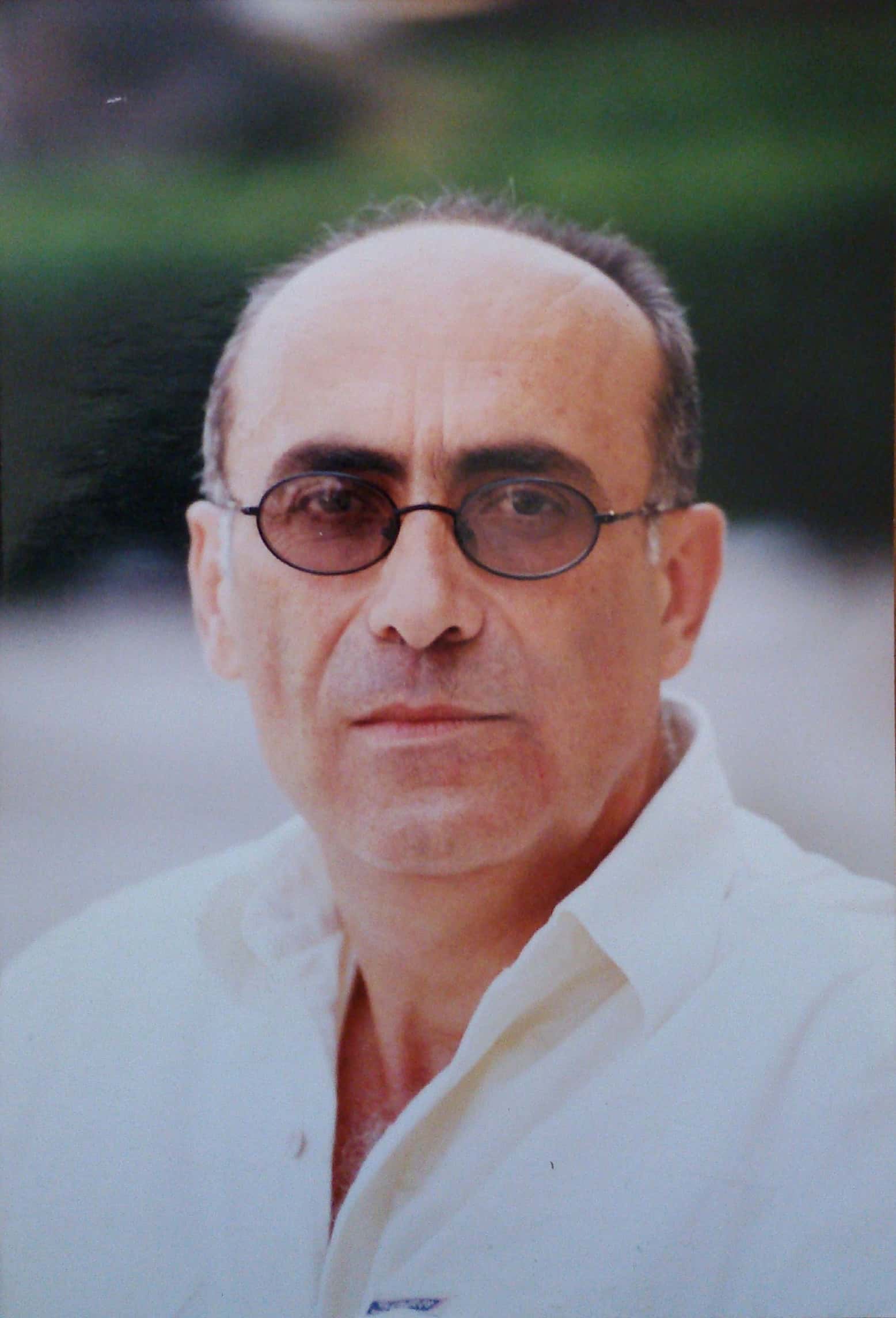

Read this essay in Arabic here. This piece is part of a limited series on shifting narratives in Syrian literature, guest edited by novelist Rosa Yassin Hassan.

Perhaps many people are ashamed to say that a narrative is independent of reality. Or, a more accurate statement might be that a narrative is relatively independent, as it cannot ignore what has happened or is happening in its time and space.

But independence appears in changes—the slow changes affecting literature, as opposed to the occasional rapid developments in reality. Sometimes, the opposite is true when art and narratives undergo revolutions while reality stagnates. Ironically, major literary or artistic revolutions target the form at first or the methods of expression, rather than the content or themes. However, themes indicate a change in the intellectual, political and ethical stances of the writers and leave a real impact on literary expression.

These uprisings, revolutions or slow transformations cannot appear as a direct change in the diverse literary genres. Besides, the division of culture in any country, whether in public or private spheres, is not immediately reflected in the differences of the artistic structure of each literary genre: poetry, theater, short stories and novels. It rather appears in the differences in discourse and the nature of intellectual tendencies. This has been the state of the Syrian narrative for the past decade. All novelists used the same artistic form, and they will probably continue to use it for a relatively long time in the future.

Signs of modernism in the Syrian novel

19 January 2021

On lust for the Syrian narrative

02 February 2021

Accordingly, the focus of any talk about changes in the Syrian narrative will tackle the search for the content of expression more than its form, which proposes an interesting technical paradox. The novelist supporting the ruling regime and the novelist opposing it will use the same narrative techniques to express widely discrepant or opposing—even conflicting—content or purpose. The themes, on the one hand, and the content, on the other, will constitute points of contention between novelists, not between narrative forms. The narrative form itself, or the familiar narrative forms, might be the impartial collective method of literary expression.

The time period at hand is quite short, although it has witnessed major historical events, decisive political changes, ethnic transformations and massive emigration, all of which do not at all correspond to this stage in time. It is legitimate to ask about the fate of literature in general, and of the novel in particular, considering that it is the most powerful and skillful literary genre in keeping abreast of events.

This question hides behind talk about the impact of reality on literature, while the impact of literature will, in fact, be left to another coming era, as it is difficult to detect this impact over short periods of time. The matter of essence to the novelist is their ability to represent reality narratively or artistically and to recreate facts and general human values. We cannot deny that we are facing another substantive difficulty related to final judgments on two matters pertaining to such observations. The first is a question of value related to the quality of narrative works, and the second is related to a quest for truth; for the narrative or narratives that succeeded in expressing the reality that has been experienced over the past 20 years.

These uprisings, revolutions or slow transformations cannot appear as a direct change in the diverse literary genres.

Comparing the themes or content of narratives alone involves many risks. Perhaps the main one is ignoring or delaying the search for the artistic value of each narrative on its own, and equating all narratives in their assessment, without heeding their artistic differences. Still, the change in narrative themes from one decade to the other cannot be overlooked or go unnoticed because of its strong presence, which qualifies it to have a real influence on altering the artistic forms of the novel in the future.

Novels that were written about the current situation wouldn’t have been possible if it weren’t for this change. Consequently, their importance stems from their role as witnesses to the present, such as in the novels of Fawaz Haddad, Nabil Sleiman, Rosa Yassine Hassan, Samar Yazbek, Khaled Khalifa, Somar Chehadeh, Dima Wannous, Nairuz Malek, among others whose names I cannot recall at this instant.

What did exile change in our narratives?

26 January 2021

Questions about growing change in Syrian narratives

12 January 2021

Upon reading several novels, we notice a number of intellectual developments in the Syrian narrative over the past decade, which were decisive in the choices of Syrian novelists, I believe, and in their artistic, literary, intellectual and ideological commitments.

It has become difficult to access the entirety of Syrian narrative works due to the wide geographical space in which novelists are scattered and the far distances between the publishing houses and readers. Therefore, the readers of some of the contemporary Syrian narrative works, especially those who supported the revolution or participated in it, are bound to notice a change in the nature of characters in novels and their perspectives of the world. The previous rules that almost governed novels have changed. In the past, characters were pessimistic, devastated and defeated, scared and subdued, or nonchalant and only cared about their individual salvation, after having suffered a series of violent defeats that affected their inner lives, and after the collapse of all the dream projects in the world. Characters reclaiming their dreams resurfaced in Syrian narratives, and, notably, the individual was no longer lonely, isolated and hopeless without any dreams. The rebellious protagonist who is isolated and alone no longer existed. Instead, characters multiplied and worked together towards a big dream, and were deeply convinced that they were capable of changing the world. Change became a life stance for them, and they united efforts to realize it, in different and various ways, according to the nature of each character and the event they participated in creating. Perhaps the propagation of this new reality across the Syrian territories contributed to giving novelists hundreds of possibilities for new characters of the same nature.

The most significant and new aspect in the Syrian narrative was the stance towards women, which reflected to a large extent the modern woman in Syrian life. Women actively and paradoxically became engaged in the Syrian reality, as opposed to the past, and in the major event that the country witnessed. Perhaps the change in the stance of the narrative towards women would only become deeper, stronger and more authentic in the coming years, thanks to the remarkable female presence in public life, on the one hand, and Syrian women’s changing perspectives of the world. Through participating in protests, leaving the country, seeking asylum and stability in other countries and achieving new laws that regulated their relationships with men, in addition to other factors, Syrian women’s ways of confronting the world were transformed, and so were their perceptions of themselves. We can see that change in many narratives written about host countries where Syrians sought refuge around the world. Perhaps the Syrian narrative written by women themselves clearly reflected this transformation—for instance the novels of Rosa Yassine Hassan, Samar Yazbek, Maha Hassan, Dima Wannous, Sawsan Hassan and others.

In the past, characters were pessimistic, devastated and defeated, scared and subdued, or nonchalant and only cared about their individual salvation.

Syrian novels written by authors living outside Syria have broken political taboos, and we can also see a radical change in the perception of many problems that have affected society, which previous novels had only tackled from afar. These novels broke the taboos and prohibitions in social life and religious inclinations. Polyphony also became a more present feature in texts, after shedding two elements: the burden of ideology or strict political stances, and the fear of conflicting ideas in the text or their potential clash with the influential forces in reality, like the political, social and religious institutions.

What we can deduce about the Syrian narrative only proves that literary independence is relative and might not be evident on the one hand, but is bound to change and be influenced, on the other hand.

In literary forms, it is difficult for literature to achieve original structural changes, especially when the time period under study is short. Such effects appear in the Syrian narrative specifically, and this narrative might constitute a model for future study in the field, as well as in another field, which is the division of Syrian novelists over their views on current events. Some do not recognize the revolution or consider it mere terrorism and vandalism. Such ideas are bound to be reflected in the content of their narratives, and we might see this reality in several narratives published by official cultural institutions, like the Ministry of Culture or the Arab Writers Union. Some might also see reality from an angle different from that of other novelists who believed in the revolution or participated in its creation. In any case, the point remains the theme or the content of the narratives, as well as the stances of novelists towards the events that took place. These stances will determine the intellectual, ethical and humanitarian value of the narrative works and their closeness to the truth, be it the realistic truth or the artistic and fictional one.

Evidently, the test of time shall be a decisive factor in assessing artistic value, which will determine the survival or demise of any narrative production—not just in the world of arts, but also in the world of righteousness, justice, fairness and human aspiration for a decent life. We will all have to wait for its fair judgment.