This article is part of the second round of our series on LGBTIQ Syria, published and commissioned by guest editor Fadi Saleh. Read this article in Arabic here.

Read part one of Sara’s reflections on childhood and LGBTIQ identity here.

Who used to run away from their reality and imagine themself as one of those “different” or “gender non-conforming” characters from the cartoons we watched as kids? Who used to love shutting the door to a room and dressing up or expressing themself the way they liked and felt?

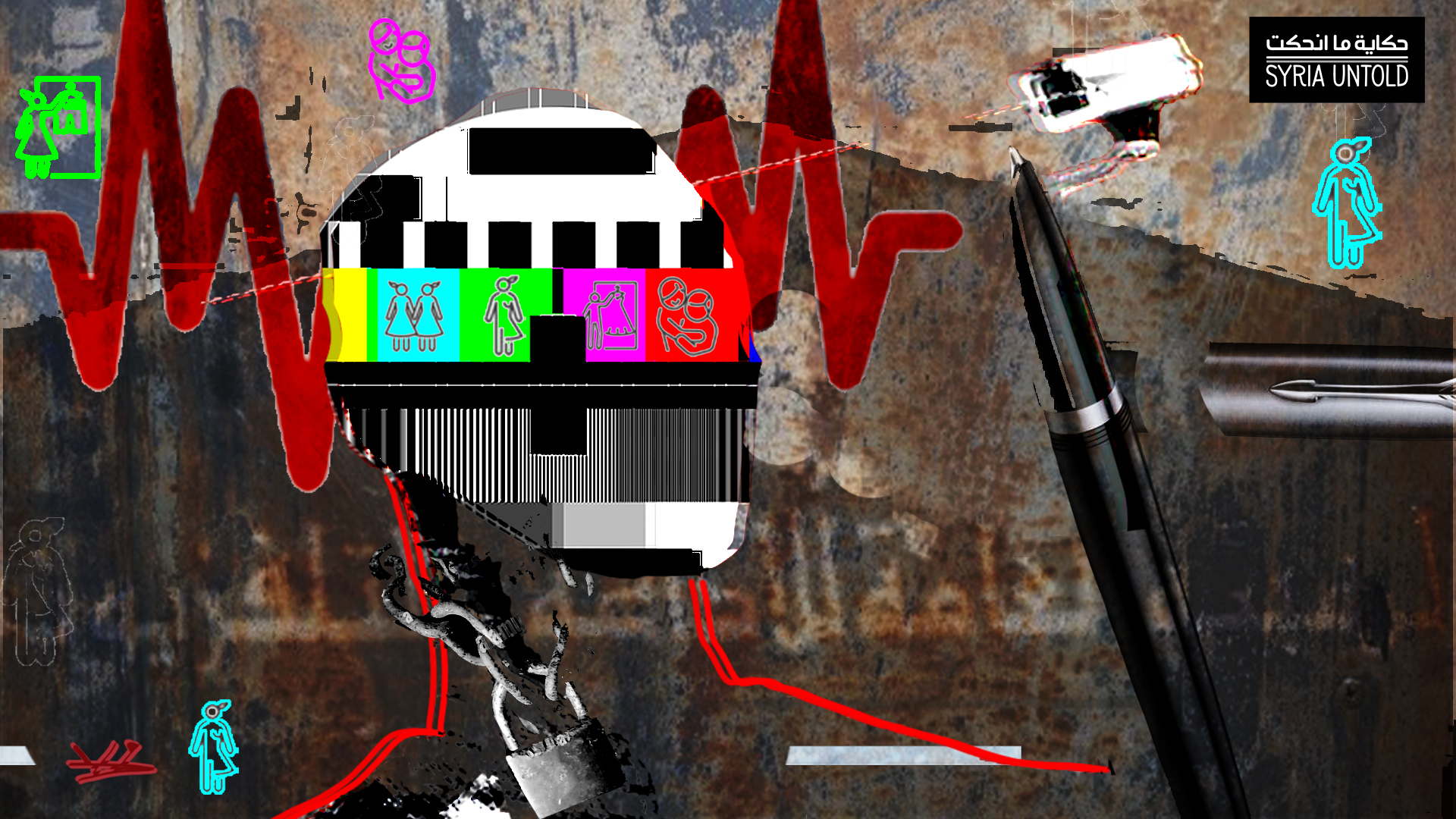

We couldn’t find ourselves in our schools’ reading and comprehension books or in the visual representations around us, so many of us accidentally found ourselves in a Japanese anime dubbed into Arabic. This particular series had characters who spoke to our sense of difference. It helped us create small spaces in our heads or in our homes in which we expressed ourselves the way we wanted.

Lady Oscar (Title of original anime series: The Rose of Versailles)

To many of us in the Syrian LGBTIQ community of the 1980s and 1990s generations, Lady Oscar was one of the first animes that gave a glimpse, a sense, a socially legitimized idea and a visual representation of what transness might mean. It showed a glimpse of queerness, or what it might mean for a cisgender girl to revolt against society and its oppressive gender roles.

When I was a child, I did not like “girl” games. I preferred to pretend that I was riding the sofa as if it were a horse as Oscar, the main character in the anime, did. If we want to talk about Lady Oscar in the context of Syria, it is very “different” from “us.” It has many queer references; you can tell that there is something more than just “innocent” love between two female characters. They tell each other things like “I love you" and “I really like you” in Arabic.

This dubbed anime was very famous in Syria, and so I wonder: Did those who dubbed it into Arabic not notice these things? Could it be that they relied too much on the fact that Lady Oscar was always mistaken for a “guy,” so we as viewers would feel okay when other women courted her? But we do know that she is a “girl”! From the very first episode, her father says he wants to raise her as a “boy,” and many of the women fall for her when “she” grows up. Apart from these queer dynamics, Oscar is a representation of a very strong “female” character. I wonder about all of these dynamics because nowadays people obsess over every little detail when it comes to anything that might look like a queer reference, thanks perhaps to social media. But it’s strange that this was not the case in the way this specific cartoon was dubbed.

‘This is how this girl grew up’

The Arabic version of the closing song in Lady Oscar tells us: “This is how this girl grew up,” as it narrates Oscar’s story. It goes on to tell of “nights that are filled with secrets.” The night is the secret place for children and their imaginations, in which they create their own worlds and happy moments the way they see fit—not as they are expected to. How many boys, for example, threw away their toys and did the things they liked in the little safe spaces they created for themselves, before having to play the gender roles expected of them the next day?

I want to tap into the happy memories of LGBTIQ people. When we revisit and deconstruct our memories, we do not always have to start from the bad, traumatizing or hurtful places. Sometimes, we could also start from those places that we liked and that left a lingering, positive trace in our memories. We as artists could draw attention to these corners, which remain forgotten or neglected due to the overwhelming challenges and circumstances we face. I love working on space and memory, on how we as kids searched for our difference, created it, lived it and found a way to embody it one way or another, either through a cartoon that we used to watch, or a period of time that we managed to spend on our own, away from the watchful eyes of family and society.

In our societies, we need to pay more attention to children. Such work is completely missing. Once we dedicate more effort to childhood in general, we can also focus more specifically on children who are “different.” At the end of the day, such differences are a reality that parents must accept. They need to understand that queerness or transness will never go away. It is true that addressing children’s issues is very difficult because everyone assumes that we, when we are children, do not know that we are LGBTIQ. While it might be true that we have no knowledge of identities and terminology, we do have a certain level of consciousness about our being “different.”

Of course, society assumes that children understand heterosexuality, religion, cis-men and cis-women, marriage, housework, childbirth, men loving women, all as part of their “human nature.” When it comes to homosexuality, transness and other kinds of difference, children are assumed not to understand anything. These are merely taboos, the reasoning goes, nothing more and nothing less. While children might be a complicated and tough group to reach, the solution is not to pretend that we do not see what they are going through, to ignore them or their problems.

Quite the opposite: Because these topics are sensitive, we need to listen to children, learn more and remember that children do understand a lot.