This article is part of the second round of our series on LGBTIQ Syria, published and commissioned by guest editor Fadi Saleh. Read this article in Arabic here.

Damascus, 1986 onwards…

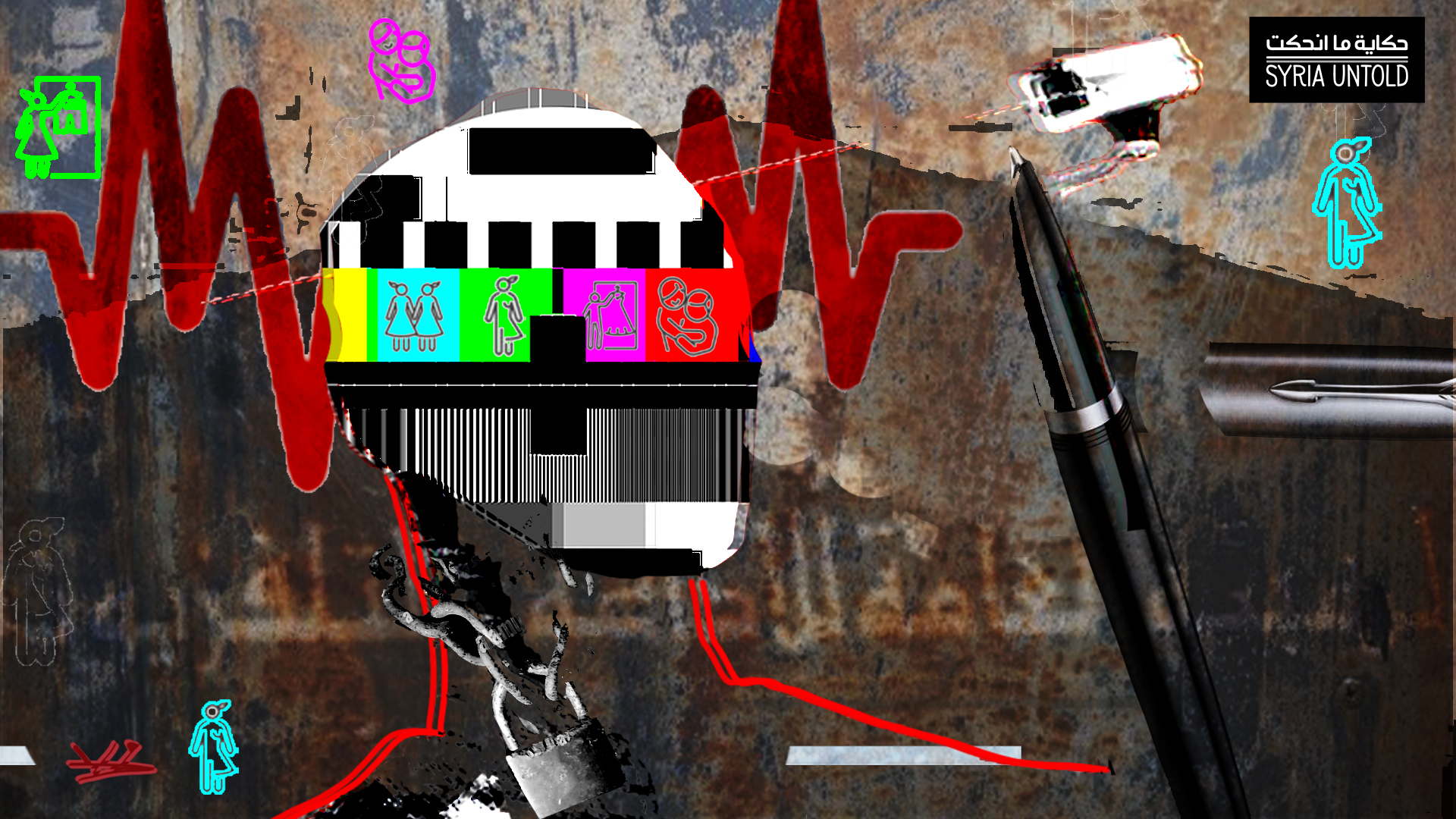

An iron curtain on freedoms, culture and any form of individual expression. We are all assumed Syrian in the same way, all heteronormative and all conformist not only to the ideal genders assigned to us, but also to our ideal party and our ideal president, whom we have to cherish. There is a feeling that if you don’t, then maybe you are not part of this community, you are not Syrian enough.

Thank you, Um Kamel!

On childhood, ‘being different’ and memory

10 June 2022

In this environment, other forms of tyranny thrived. You could find them in family, school, university or on the street. They assumed we all have the same gender experience, listened to the same music, read the same books or believed in the same god. Any deviation would outcast you and you’d no longer be part of the community.

With all this, a strange type of idealistic, conformist and conservative culture was being produced confirming all these assumptions like an unstoppable propaganda machine. And so to exist, I had to create my own subculture. Create my own symbols to relate to, create spaces to think, to love, to maneuver the rules and, eventually, to protest and then do all that at once.

So many small individual revolutions leading to a final stand between who we are and who we are assumed to be socially, politically and ideologically. That was the moment of the revolution against the dictatorship that gave space to all this tyranny, the moment we realized we were different, and very briefly we were able to celebrate that difference and defend it.

Whether or not I win this battle/idea will remain a question as long as I live, but it remains my belief that only tyrants assume that all are of the same image. Defending our differences will remain one of the means to combat this tyranny, whatever its form.