This report is published through cooperation and partnership between Syria Untold and the “Nirij” network for probing and exploratory journalism.

A Thursday evening in September, 2015, Said (alias, 45 yrs. old) sets out on his first journey from the Damascus countryside to the Defence Ministry plants in the regime-controlled province of Hama. He’s carrying metal parts which, at the start, he didn’t know what they were being used for but finds out quickly when his load exploded.

“The explosive barrels that we heard about, I transported them in my truck on the return trip... I’m not a participant in that crime. I was forced to do it. I could not refuse,” he later reported. Said was forced to transport materials specific to the production of explosive barrels to places that manufacture them, and which are used in killing civilians and the decimation of homes and residential buildings in areas under the control of opposition forces in several Syrian provinces.

Abu Husam (alias) is another truck driver from the city of Dariya in the Damascus countryside. He considers himself a participant in transporting a load of the same material to one of the military airports responsible for bombing his city. “I knew that some of the planes that bombed my city left from that airport,” he said. “I didn’t know if it would kill my brother blockaded in the city or would destroy my house.”

“I knew that some of the planes that bombed my city left from that airport,” Abu Husam said. “I didn’t know if it would kill my brother blockaded in the city or would destroy my house.”

This investigation confirms the Syrian regime’s exploitation of the Mobilization Act issued in 2011. The law subjugates citizens to transport arms, munitions, and military materials including explosive barrels and the materials used to make them from Defence Ministry plants to the airports and military sites dispersed throughout different Syrian provinces, along with involving them in the transportation of chemical weapons and the particular materials needed to fabricate them.

How does the regime compel these individuals to transport explosive materials and barrels? How many loads have been transported? What roads do they take? What is the fate of those who refuse to cooperate? What dangers do the drivers encounter? This investigation attempts to answer these questions and more.

What is the Mobilization Act?

“The Mobilization Act” issued by presidential decree by the head of the Syrian regime Bashar al-Asad on August 21, 2011, No. 104 defines mobilization as “the transformation of the country in general and the armed forced in particular from time of peace to a time of war in preparation to face internal and external dangers whether by catastrophes natural or unnatural,” delineating in the tenth article civilian obligations during mobilization. One of the clauses specifies “the submission of all what is necessary of real estate properties and transportable properties and other articles that are or were in their possession.”

In Article 13, the act defines the obligation associated with the submission of means of transportation, among them “securing means of transportation for the sake of securing the armed forces during mobilization,” though the act generalizes all military and civilian institutions in addition to “citizens owning means of transportation.”

The strategic expert and military analyst General Ahmad Rihal said that the necessity of the mobilization decree is not new, and the amendments were generally recognized before 2011. The Syrian regime, though, wanted to authorize this “legally”, being that the laws allow him to do this under the title “preparing the country for war.” This allows the regime to transform the economics of the state and civilian sectors to benefit the war efforts. Among the most outstanding clauses is placing all machines in Syria under the auspices of the military institution.

How does the regime compel civilians to participate in transporting explosives?

“We need you on a mission for one day with your car...a return trip to transport some necessities.” This is what the officer responsible for the “town center” checkpoint affiliated with the airborne secret police situated on the “Daraa’ -Damascus” road close to the city of Sahnaya told Said after stopping him on his way to the capitol city Damascus, without elaborating on the contents of those necessities.

Said explains his acquiescence: “There was no option...if we haven’t died yet, we’ve seen those who have,” signaling the impossibility of resisting.

“There was no option...if we haven’t died yet, we’ve seen those who have,” signaling the impossibility of resisting.

Originally from the city of al-Qunaytra, he further explains: “I got out of my car upon request of the officer and sat near the checkpoint at the blockade for more than two hours, during which one of the members of the group took my car somewhere that at the time I had no idea where.”

“After waiting for a long time,” he continues, “I thought they confiscated my car, and that my arrest was impending, so, I decided to give it up and save myself. I ask the leading officer if I could go home and leave the car with the unit until they are finished with the job. He refused, saying: We don’t lack in securing cars. With these missions in particular you are more important than all the trucks.”

Said’s car returned carrying iron cylinders covered with cloth tents that were hard to see through, making it hard to figure out what was inside without getting close. The officer instructed one of the members of the blockade unit to accompany Said in delivering the freight without telling him where. After passing the blockade, the military personnel said the two of them were heading to the region of Hama.

The trip lasted nearly five hours when they finally arrived at “Defense Ministry plants” in the township of Taqsis in the Hama countryside. Said added, “As soon as we arrived at the main entrance of the Defense plants I was ordered to get out of the car by the head of a group of guards. The military personnel drove the car through the entrance and returned in less than an hour, ordering me to get in and return to Damascus.”

“On the trip back the military personnel starting talking with me and asked where I lived and worked,” he concludes. Said discovered during their conversation that they were carrying materials specific to the production of explosive barrels to the places that manufacture them, and which are used in killing civilians and the decimation of homes and residential buildings in areas under the control of opposition forces in several Syrian provinces.

In a similar mission, Shadi (alias, 39 yrs. old) from the city of Homs, set out at the end of April, 2016 from the region of Husya in the Homs countryside to a military region at the outskirts of the city of al-Safira in the Aleppo countryside, after he was stopped at the Husya military checkpoint when he was headed to the Industrial City.

Shadi, who drives a large truck that transports dirt and rubble says: “The military personnel responsible for searching trucks at the checkpoint signaled for me to stop on the side of the road. In no time, the officer in charge of the checkpoint headed over with four military personnel immediately apprehending my car and demanding that I bring the personnel to the city of al-Safira and return to the checkpoint once again to get back my identification card which he had confiscated.”

The truck driver narrated that immediately upon his arrival he left his vehicle inside the military site and exited by the main gate as commanded by one of the officers. Then military personnel returned with his truck that was carrying more than ten explosive barrels and weighed more than four tons.

“I was directed by the militants to head toward the Hama military airport to empty the load there,” he added. “Then I got a military mission from inside the airport that allowed me to return on my own to the Husya checkpoint to retrieve my identification card.”

“It was the only time that I participated in a transportation operation for the benefit of the regime” he concludes. “I was asked to participate in another operation, but was able to save myself by paying 300,000 SL (about $600 US) to the al-Rustan checkpoint militia in the northern Hums countryside as compensation.”

Abu Husam (alias, 50 yrs. old) is from the city of Dariya in the Damascus countryside. He also participated in a transportation operation of explosive barrels from within the Mezza military airport to the Bali airport situated on the administrative border between the provinces of the Damascus countryside and al-Suwayda, after being stopped just before one of the central military checkpoints on the connecting road between Ma‘adamiyat al-Sham city and the township of Jadidat ‘Artuz the morning of September 10, 2015.

“I went to the Mezza military airport on my own, and as soon as I arrived my truck was filled with numerous explosive barrels”

“I went to the Mezza military airport on my own, and as soon as I arrived my truck was filled with numerous explosive barrels,” he says. “The weight exceeded hat is allowed for transportation trucks. Two military personnel wearing civilian clothes rode with me from inside the airport. Then we headed to the Bali airport to unload the freight after which I returned, in the company of militants, to the Sahnaya checkpoint to retrieve my documenting papers.”

He continues: “At that time, the battles in Dariya were incredibly fierce, and I knew that some of the planes bombing the city left from the Bali airport, and that I was a participant in transporting the barrels to the airport that were thrown on my city...not knowing whether they would kill my brother blockaded in the city or destroy my house.”

Why does the regime rely on civilian machines?

Since 2011, the Syrian regime has relied on machines and trucks belonging to the civilian sector to transport freights of arms and other specialized military materials for the army being that the Transportation Administration of the Syrian Ministry of Defense doesn’t have enough machines itself able to transport and deploy the army across Syrian lands, according to General Ahmad Rihal.

Rihal clarifies that Edict 104 issued in 2011 and known as the Mobilization Act imposes a standing order to civilians to allocate their cars and trucks for the benefit of the war effort. He added that the weakness of the military’s means of transport is what propelled the regime to issue the edict. “The trucks under the auspices of the military institution were no good for the transport operations, they were worn down and used up too much fuel, basically one liter for every kilometer. This is what set off the rising costs on transport operations that were basically valued at the same price of the freight.” Major Yusuf Hammoud also confirmed this to Syria Untold and Nirij.

The major, a pilot who had defected from the Syrian army on November 9, 2012, said that during the first three years of the Syrian revolution, opposition groups went after the roads used by the military personnel and regime groups, cutting off the roads and making the military tools, cars, and trucks that transport arms and munitions between military sites and central outposts susceptible. This is what pushed the regime to rely on civilian vehicles to insure they couldn’t accomplish their goals. “With the development of the opposition’s military, it increased the danger of transport missions for the regime,” he continued, “so they relied on cold-storage vehicles carrying vegetables in their operations.” He confirmed that in this way the Syrian regime transported air defense stations and defense missiles, and other military materials. As well, the regime resorted to using civilian vehicles to transport provisions and other military materials to sites blockading different cities and towns.

The major, who did his military service at al-Seen” military airport located on the Damascus-al-Damir road, added that he had witnessed the use of civilian vehicles in August 2012 during the operations transporting military resources - arms and munitions, as well as foodstuffs to the airport and neighboring military sites, whether in the neighboring area of Abu al-Shamat or in the cities and towns of eastern al-Ghouta, pointing out that airport leadership relied on civilian vehicles being that the area was seeing the spread of opposition groups.

According to Hammoud, at the beginning of 2012 he witnessed an operation transporting the 35th battalion, special troops of the regime’s army, from Damascus to the city of Jesr al-Shugur in the Idlib countryside by way of civilian trains, illustrating further the complete confiscation of trains to transport troops to Idlib in just a few days, allowing them to avoid exposing the immensity of their forces during transport.

Fuel for the Interior Fronts

It’s not the explosive barrels alone that brought about using civilians for transport, but rather they were used in operation to transport arms, munitions, medical goods, and foodstuffs to regime fighters on the front lines in areas that witnessing battles between the regime and opposition groups in different provinces. Additionally, they were forced to transport groups of personnel and supporting supplies. This is what was forced upon “Said” during his second mission that included transporting medical and food materials to one of the military points in the area of Khan al-Shaykh in the Damascus countryside after being stopped at one of the regime checkpoints on the “al-Qunaytra-Damascus” road in the middle of 2016.

“I was stopped at the Sa‘sa‘ checkpoint belonging to military security and was sent in the company of two of its personnel to al-Talaa’a encampment in the Naba‘ al-Fawar region in the al-Qunaytra countryside, which was a main military resource outpost in the region,” Said says. “There, my truck was loaded with medical and food supplies. I was given a military mission to transport the goods on my own to the 68th brigade, part of the 7th troop on the outskirts of the Khan al-Shaykh region across the main road.”

Said was refused entrance by army guards at one of the subsidiary entrances under command of al-Samah brigade, forcing him to enter by the main gate located on al-Salam Autostrade that was at the time cut-off by a civilian movement. It was considered a military zone and was filled with ambush sites and military outposts loyal to the regime on one side and opposition groups on the opposite side.

“Tons of questions haunted me as I drove down that road...Will I be ambushed and die, susceptible in my car? Will I be arrested by one of the opposition groups? What would convince them that I was forced to transport these goods carrying out a military mission? What if I flee with the truck without delivering the freight?”

He describes that day: “Tons of questions haunted me as I drove down that road...Will I be ambushed and die, susceptible in my car? Will I be arrested by one of the opposition groups? What would convince them that I was forced to transport these goods carrying out a military mission? What if I flee with the truck without delivering the freight?”

While heading from “Suq al-Hal” in Damascus to his city al-Kaswa in western Damascus, Alaa’ (alias, 33 yrs. old) was stopped at one of the central military checkpoints on the outskirts of the capitol. About 20 military personnel rode in his truck after emptying it of the vegetables inside. They demanded he head in the direction of Harasta in eastern al-Ghouta where battles had ignited in the surrounding areas at the end of 2017.

“The directives of the officer were to head to the first military outpost in Harasta to deliver the personnel. But after arriving there, I was unexpectedly loaded with a number of boxes that contained their ammunition and was told to enter deep into the city where the battles were taking place.”

Alaa’ adds: “A friend of mine was a member of the regime’s army. I contacted him and asked him to intervene on my behalf to excuse me from the mission. I was excused after his commanding officer intervened, but without my vehicle. After agreeing with personnel, he asked me to leave the vehicle with them to deliver munitions and that it would be returned to me after they finished their job.

“Forget the vehicle and move on...our young men are dying and you’re worried about your vehicle?”

“Forget the vehicle and move on...our young men are dying and you’re worried about your vehicle?” This is what the commanding officer at the checkpoint said to Alaa’ after waiting for more than 3 hours for the return of his truck. “Until this day I don’t know what happened to my vehicle,” he concludes, “and I wouldn’t be able to recover it without the intervention of a number of middle-men.”

Nur al-Khatib, a member of the Syrian Network for Human Rights said that most of the cases that they were able to authenticate were the confiscation of civilian trucks and their use for military objectives like transporting munitions and personnel. The other kinds of cases were that the Syrian regime forced them to drive vehicles during the transport operations, and making them to do this work for specific amounts of time. She made clear that these methods of mobilization and confiscation were happening in all the Syrian provinces in which there were military activities during the last ten years, and most often in Homs and Hama.

As for the nature of the materials being transported in civilian vehicles, al-Khatib made clear that various munitions and military personnel were more numerous than explosive barrels, and she confirmed that most of the civilians didn’t know what they were transporting.

How much freight was transported?

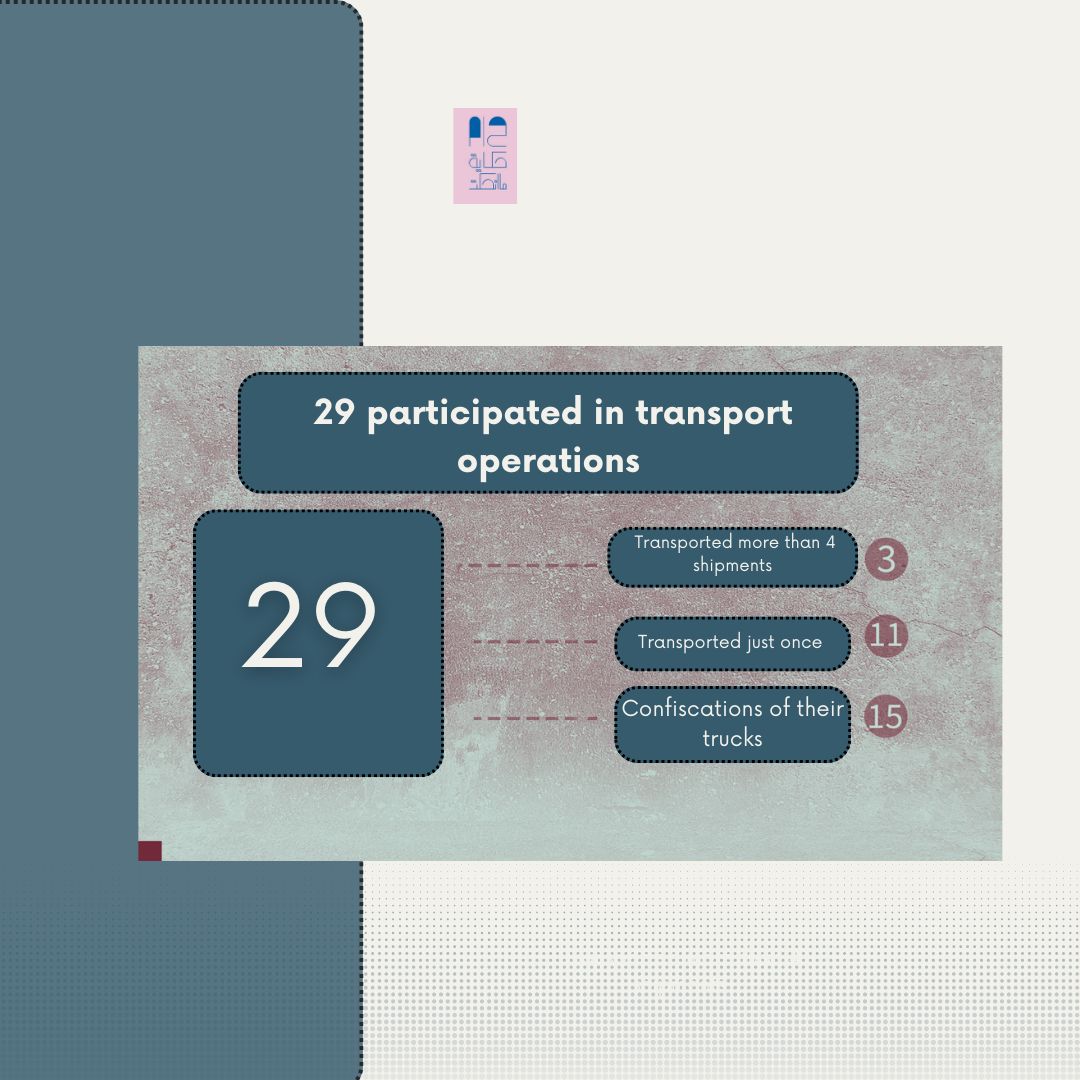

In a poll conducted in preparation for this investigation, hundreds of drivers of transport vehicles, both medium- and large-sized, from five provinces of Syria: the Damascus countryside, al-Qunaytra, al-Suwayda (southern Syria), and Homs and Hama (in the west), it became clear that the percentage of civilians forced to transport arms and explosives for the benefit of the Syrian regime varied according to the objective, number of loads, and kind of arms transported.

From those drivers participating in the poll, distributed according to the five provinces mentioned above, 29% of them participated in transport operation of various types and natures. Those from Hama and the Damascus countryside were the largest percentage of participants. According to the drivers, the dissimilarity of the numbers differs between one province and another, depending on military and security situations that the area had previously undergone.

Three of the truck drivers said that they transported freights of arms and explosives between the Defense plants and the war and military airports in the different Syrian provinces more than four times during the years between 2013 - 2019. Meanwhile, 11 of them said that they transported freight only once. At the same time, 15 transport vehicles were confiscated at military checkpoints surrounding the areas that were undergoing military activities during the aforementioned time period to be used in the transporting of arms and munitions to advancing front lines.

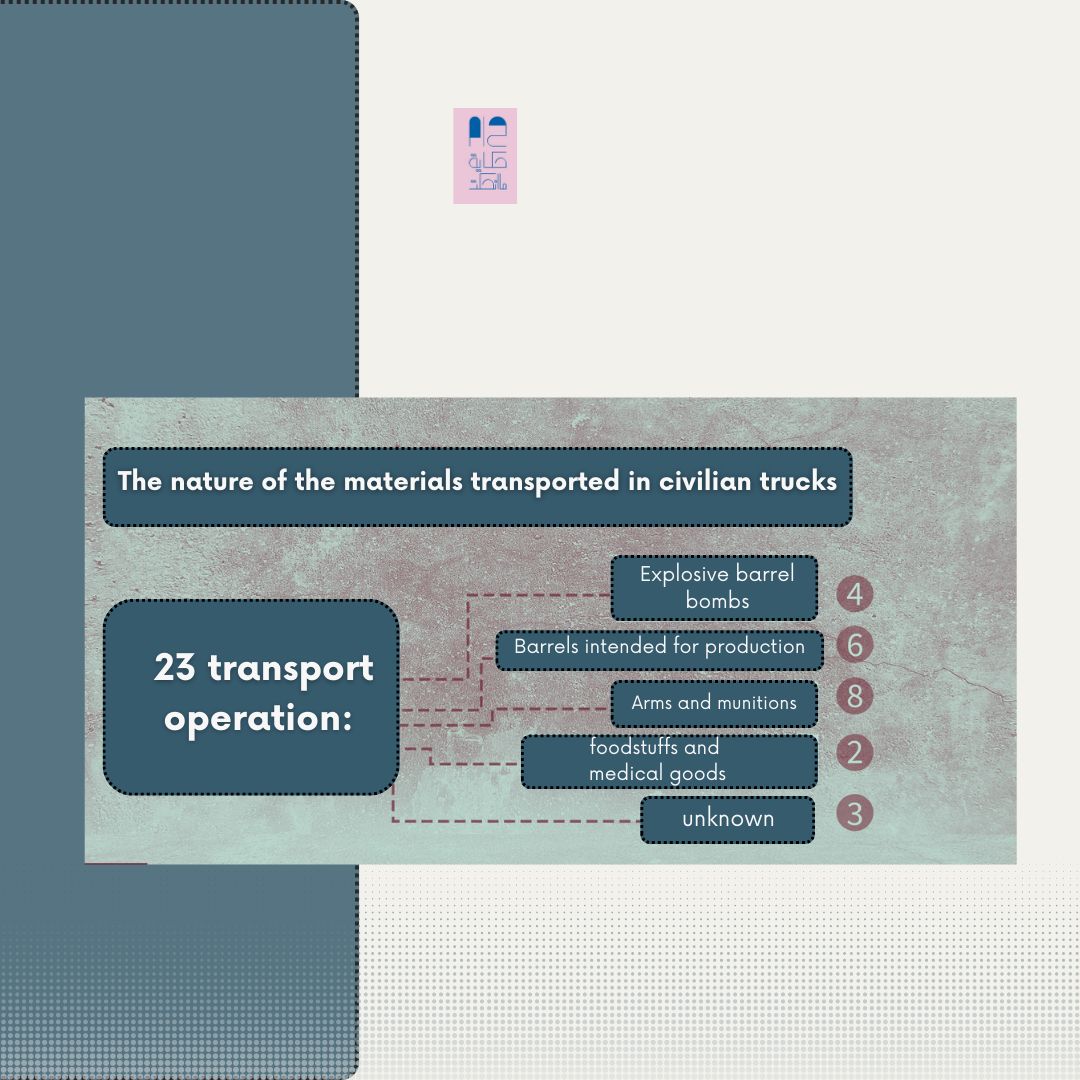

In terms of the contents of the cargo loads, four of the drivers said they transported explosive barrels from military sites to war airports. Six of the drivers transported empty barrels intended for production. Eight of the drivers transported arms and munitions to advancing front lines in war zones, and two drivers transported foodstuffs and medical goods to military personnel on the front lines as well. As well, three of the drivers were unaware of the kinds of material they transported with their vehicles, keeping in mind that some of the drivers partaking in the poll participated in different transport operations a number of times.

The drivers were all in agreement that the number of military personnel accompanying all the trucks that were used for transport, wavered between two and four persons, without any barometer to measure an increase or decrease in the number of accompanying military personnel. As well, they were all in agreement that the accompanying personnel intentionally wore civilian clothing in their trucks no matter the differing places of service between the regime’s army or the security apparatuses.

Data from the Syrian Ministry of Transportation reveals that by the end of 2021 the number of registered vehicles in Syria had reached 2,000,472 vehicles, without classifying them. At the time, a source inside the ministry - who asked his name not be used for security reasons - confirmed that the number of transport vehicles in Syria reached close to 815,000 trucks, almost 33% of all registered vehicles. Among those, almost 345,000 large and enclosed trucks, and 470,000 small trucks.

The defector, Major Yusuf Hamud, clarified that the mechanism of relying on civilian vehicles to transport military material and equipment differed according to the nature of that which needed to be transported. As such, the regime relies on enclosed refrigerated vehicles that transport meat and vegetables and small trucks to transport arms and munitions, while large trucks are used to transport explosive barrels and large military equipment, and Mac trucks for military machines and tanks, as well as relying on busses, i.e. pullman to transport military personnel between Syrian regions.

Hamud noted that “the regime relied on the confiscation of trucks to use in transport operations in the form of military convoys in which civilian drivers were used to transport munitions from one area to another, most of the time dispatching two or three military personnel to accompany the drivers who more often than not were wearing civilian clothing and carried their civilian identification cards in addition to their military ones. Whereas, the activity of transporting explosive barrels took place from Defense plants to airports and other military war airports.” Hamud points out that the airports are spread out in regions far from sites that produce explosive barrels.

Hamud confirmed that the regime forced a group of small truck drivers at the beginning of 2014 to transport a lab for chemical substances, which was completely taken apart, from Defense labs in the area of Khan Tumaan to al-Nirb military airport in the Aleppo province by way of the al-Safira city road. It was then transported by air from the airport to the city of Masyaf in the Hama countryside where it was put back into operation anew.

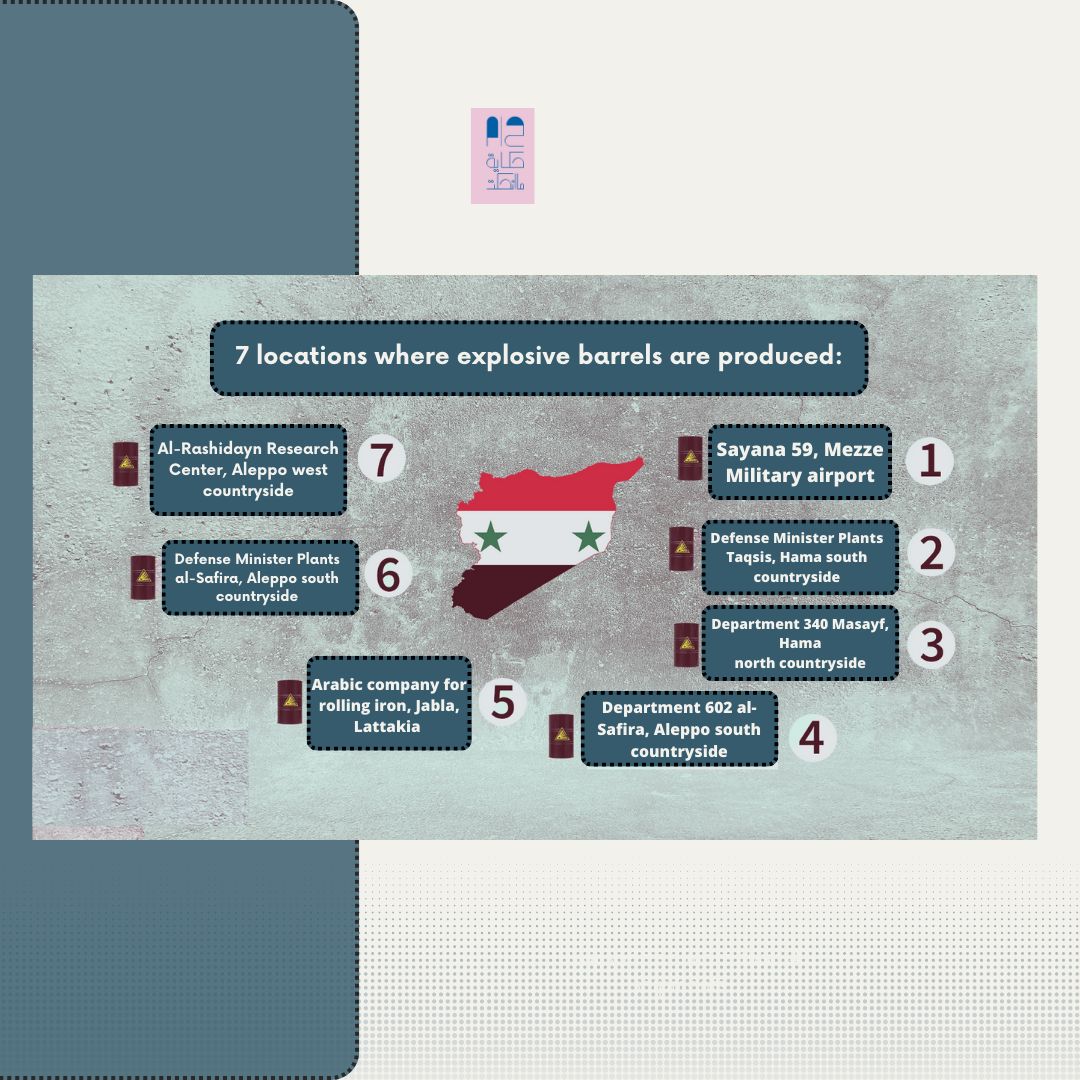

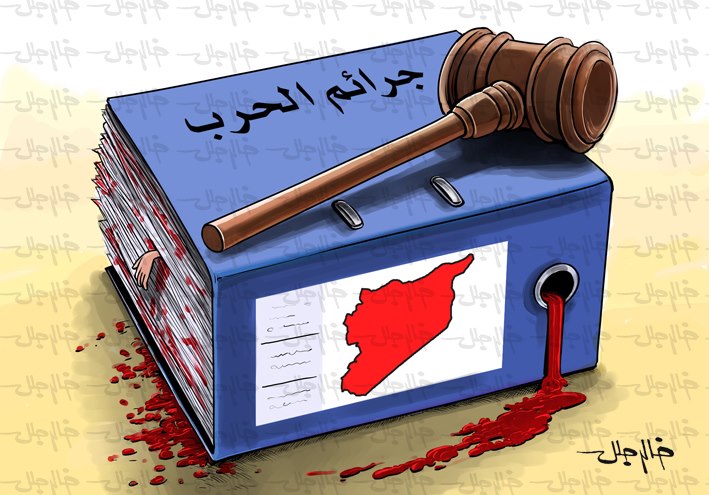

In a previous report, the Syrian Network for Human Rights exposed seven sites in Syria that specialize in the production of explosive barrels. Among them are the Defense labs in the township of Taqsis in the countryside of the southern province of Hama; Defense labs in al-Safira in the south eastern countryside of the province of Aleppo; the 602 Branch under the auspices of the General Directorship of the Center of Scientific Study and Research in the area of al-Safira in the south eastern countryside of the province of Aleppo; the 340 Branch of the same agency in the northern region of Masyaf in the northern countryside of Hama; additionally, the economic unit of the Al-Rashidin Research Center west of the city of Aleppo; the headquarters of the Arab company for rolled iron in the city of Jableh in the province of Latakia (al-Ladhaqiya); and the Conservation and Preservation Unit 59 at the Mezza military airport in the Damascus capitol. The Network confirms that all the barrels are amassed in two airports: the Hama and al-Nirb military airports in the province of Aleppo after being filled with explosive substances. These two airports then supply all the military airports in Syria with the barrels to use in attacks.

Application of law in a manner “outside the law”

In discussing the “legal” transgressions in the mechanism of applying the law, Khalil (alias), a lawyer living in Damascus, says that issuing the Mobilization Act came about to actualize military goals exclusively, and at a time when the military authority was regarded above all other laws, and is what increased the recorded violations within the “legal transgressions” clause.

Khalil explained that the proper mechanism for applying the Mobilization Act is determined by sending mobilization notifications across administrative subdivisions and police departments, similar to notifications of individual mobilization sent through the Ministry of Interior to police departments and neighborhood leaders to notify those within, and which included a period of seven days for the individual to turn themselves in. It’s evident that officers and military personnel of the regime applied this decision in an “unlawful” manner as seen by cases of confiscations and arbitrary detentions.

Law No. 10: Property, Lawfare, and New Social Order in Syria

26 July 2018

Khalil clarified that the law specifies the taking over of vehicles and trucks in the presence of a commission presumed to undertake a search of the contents of the vehicles and providing the owners official documents that specify a place and time that the vehicle will be returned after the mission. In addition to a list describing the contents of all the vehicles. This is also what the regime has excluded in its application of the law.

He further says: “In addition to that is the transmuting of this law into a source of profit for some officers and military personnel spread across the military checkpoints by demanding monetary payment instead of confiscating the vehicle and a monetary payment for the return of it after the mission. Absolutely, this is considered a violation of the mobilization act and the Syrian constitution that stipulates the protection of civilian possessions in one of its articles.”

A number of drivers whose vehicles were confiscated by the Syrian regime on account of the mobilization law mention that they never received any document that the vehicle is at one of the checkpoints or military barracks. Adding, the mobilization operation happened without receiving a notification of mobilization beforehand, or a period of time to finish their work before turning over their vehicles. Nur al-Khatib, the Syrian Network of Human Rights representative we talked with confirmed this as well, saying that the operations of mobilization and confiscation happen without any summons or official request on behalf of the Mobilization Commission or Department of Enlistment/Conscription or military institutions. She believes the mobilization that is being exercised on civilians has no relationship the Mobilization Act, rather it is “closer to militia operations” because they are conducted without any oversight, and without granting civilians official document for what was confiscated and how they would be compensated or returned to them.

What is the fate of those who refuse?

The law stipulates punishments in Article 33: imprisonment from three months to two years for all who oppose the decree in preparing for mobilization, or in the execution of it, or in carrying out experiments and training for it, or obstructing the mobilization of it. Article 37 defines the punishment of imprisonment for six months to a year on all who refuse the order of the summons, and all who refuse to continue the work defined for them according to the demands of mobilization.

Nur al-Khatib states: “Civilians don’t have the choice to refuse. Most of them give up their vehicles because the fear of arrest.” Emphasizing, that in the event a civilian inquired about the fate of his car, he’s not given a precise answer, and his car is taken by force after threatening or beating him.

“Civilians don’t have the choice to refuse. Most of them give up their vehicles because the fear of arrest.”

She makes clear that many civilians resort to paying a monetary sum to military personnel at the security checkpoints and roundabouts so that their vehicle is not confiscated. This is what opens the door to major acts of fleecing and exploitation of civilians possessions.

From his perspective, Major Yusuf Hamud says that “the fate of drivers who refuse to participate in transport operations is like the fate of any Syrian refusing to undertake an act for the benefit of the regime after being commanded to do so, resulting in his arrest or execution.” Making clear that “civilians stand between two dangers: the first being arrested at the time of refusing to carry out the mission, and the second being the danger of being exposed to opposition forces while carrying out the operations.”

Annulling the law...would it return one’s due to its rightful owners?

On August 8, 2020, the General Administration for Mobilization of the Syrian army annulled the Mobilization Act which was used to justify the confiscation of machines and vehicles for military purposes. This led to general instructions issued by the office of the president of the regime Bashar al-Asad in his capacity as the public leader of the army and armed forces which includes stopping all measures of confiscating machines and engineering materials and work in accordance with the Mobilization Act and his executive directives.

A picture of the annulment decision

Following the general instructions to annul mobilization, Bashar al-Assad instated a law, No. 20, in 2021 to organize settlement in situations involving vehicles, machines, engineering materials, and the human crews associated with them that were conscripted by way of the General Administration for Mobilization for the benefit of “the war effort,” and to compensate their owners for damages that incurred on these machines. Additionally, compensating the human crews for a sufficient amount on limited bases. This is an official settlement of the servitude of owners and truck drivers for military objectives represented by the transporting of arms, munitions, and explosive materials to the front lines.

Mansur (alias, 40 yrs. old) was able to find out where his vehicle was in the city of Hama after being confiscated more than four years earlier at a checkpoint subjugated by one of the local militias on the outskirts of the city.

“Members of a checkpoint confiscated my car in the beginning of November 2017 when I was heading to work in the city of Hama. The military persons told me to come back to retrieve it in ten days when they would be done with it, without giving me any documentation to prove they had it. But upon my return to get it back, I faced threats of arrest if I came back to ask for it again. It stayed with them for four years without my knowing anything about it.”

“Members of a checkpoint confiscated my car in the beginning of November 2017 when I was heading to work in the city of Hama,” he says. “The military persons told me to come back to retrieve it in ten days when they would be done with it, without giving me any documentation to prove they had it. But upon my return to get it back, I faced threats of arrest if I came back to ask for it again. It stayed with them for four years without my knowing anything about it.”

Mansur adds: “In the beginning of 2018 I stumbled onto my car by way of one of the real estate brokers in Hama. I immediately hired a lawyer to raise a legal appeal for its return. That’s what we did, but we were only able to get it back after paying a sum of one million SL (the equivalent of $4,000 US at that time) to someone who was holding it, claiming that he paid this sum as a down payment to buy it from someone else. He wasn’t able to transfer its ownership so he refused to pay the rest of the price.” “That was the lawyer’s advice,” he concludes. “If I hadn’t paid that sum, then my legal appeal would still be stuck in police departments and courts until this day.”

Khalil (alias), the lawyer living in Damascus says that since 2020 to today there are more than three hundred legal appeals stuck in the courts of Damascus and its countryside. Most are connected with the return of vehicles confiscated in accordance with the Mobilization Act. Adding that the vehicles that have been returned is not more than 2% of confiscated vehicles, and these have been under special conditions, such as the vehicle being sold to someone associated with security matters by way of an officer, and the security apparatus divested of the vehicle afterwards. Or the owners’ identities were disclosed and their positions curtailed by the courts.

Khalil clarified that the tool of forwarding a legal appeal includes presenting the appeal with ownership papers, pointing out that the courts don’t assign any directive to search for them, and are satisfied with issuing search notifications to transit and police departments to stop the car in case they pass it during their patrol.

According to the lawyer, most of the confiscated cars pass through the provinces with fake license plates and rely on the security apparatuses to ease traveling through them, making the act of finding and seizing them practically impossible.

Alaa’ transformed from being the owner of a truck transporting vegetables to a porter in Suq al-Hal in Damascus after his truck was confiscated in the outskirts of the city of Harasta in eastern al-Ghouta more than six years ago. This was the only source of income for his family who has trouble securing daily provisions. This is the situation of Said who despite returning with his truck after his second mission hastened to sell it so he wouldn’t be pressed into missions like that again. As such, his source of livelihood that he had done in the company of his father since he was young was cut off, and he has yet to find another line of work.