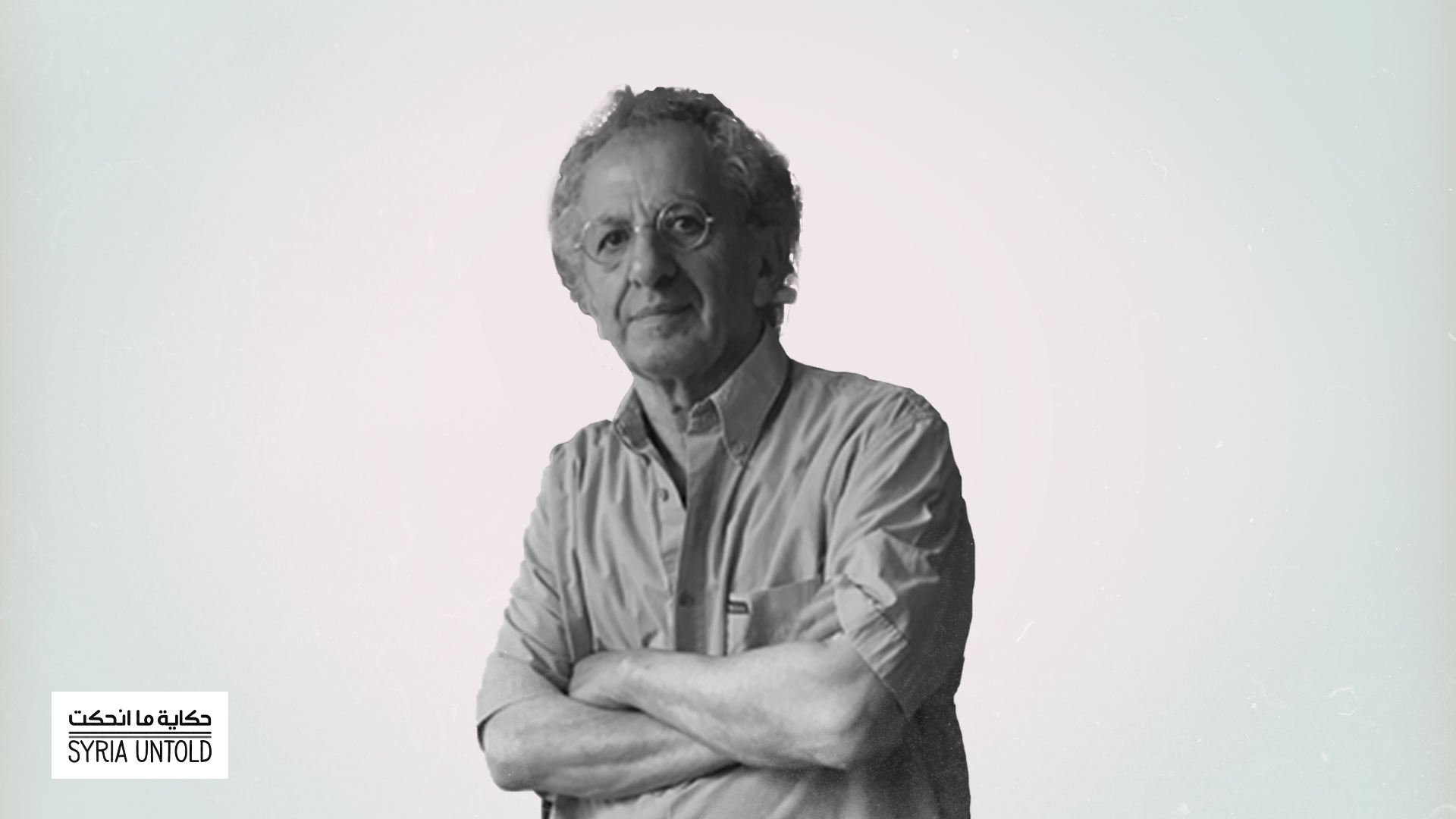

It’s rare to find a sculptor who voluntarily destroys a monumental work that he spent months creating, transporting from place to place, and restoring. Yet, the Syrian sculptor Khaled Dawwa, accustomed to confronting dictatorship and its toll on his homeland, Syria—sometimes by building, other times by destroying—did exactly that on 30 August with his over-three-meter-tall statue, “The King of Holes”, directly in front of the United Nations building in Geneva. Alongside families of detainees and forcibly disappeared individuals, numbering over 100.000 at the hands of the Syrian regime, Dawwa undertook this act, hoping the UN would fulfill its commitment to uncover their fates through the "Independent Institution for the Missing" in Syria, established by the United Nations in June 2023. In this interview, conducted in stages over the phone, we delve into Khaled Dawwa’s professional journey in Syria, and especially in his decade-long exile, where he has dedicated his work to the Syrian cause. We aim to understand whether, as a former detainee, he feels bound to the "unfinished" Syrian story, or if he has found a way to move forward with his life in France.

In press statements, you mentioned leaving "The King of Holes" in a public place to be consumed by nature, highlighting its fragility. When did you sculpt it, and how did the idea of its destruction in an art performance come about, in front of the United Nations headquarters in Geneva on the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances, in which families of detainees participated? How difficult was it for you to destroy it after years of creating and exhibiting it in various places?

The project to exhibit "The King of Holes" in a public space began in 2021 as part of a competition with the "Le Socle" foundation in Paris. I participated in a contest organized by the Paris Municipality to utilize public spaces, which were allocated to art institutions or given temporarily to artists to showcase their works. The public voted online for various projects, and my proposal was selected among others. Usually, the artwork is displayed for three months, but "The King of Holes" remained on display for eight months in a prominent location, Saint-Martin. The concept evolved from displaying a small version of "The King of Holes" to a large, three-meter-high version.

The idea for the statue had been with me for a long time, but this was the first time I created a version of this scale using non-durable materials meant to be left outdoors. I learned a great deal during the creation process, took risks, and completed the work in 40 days. It was displayed in Paris for eight months, then moved to the Jardin des Sculptures in Normandy, where it remained for two years. I knew the artwork wouldn’t last long in the natural elements since it was made from fragile materials, so I had to restore it at different stages. Over those two years, plants started growing inside it, and worms inhabited it. I documented every stage of the statue's creation, considering whether to preserve it by casting it in bronze or to film it as I destroy it, making it part of a later film about the statue. Around this time, the "Syrian Campaign" organization contacted me to arrange a joint action for the International Day of the Disappeared on 30 August, during a vigil for the families of the detainees. Given the limited time left before the event, and after evaluating several ideas, we settled on the concept of destroying the artwork in collaboration with the families as a form of protest.

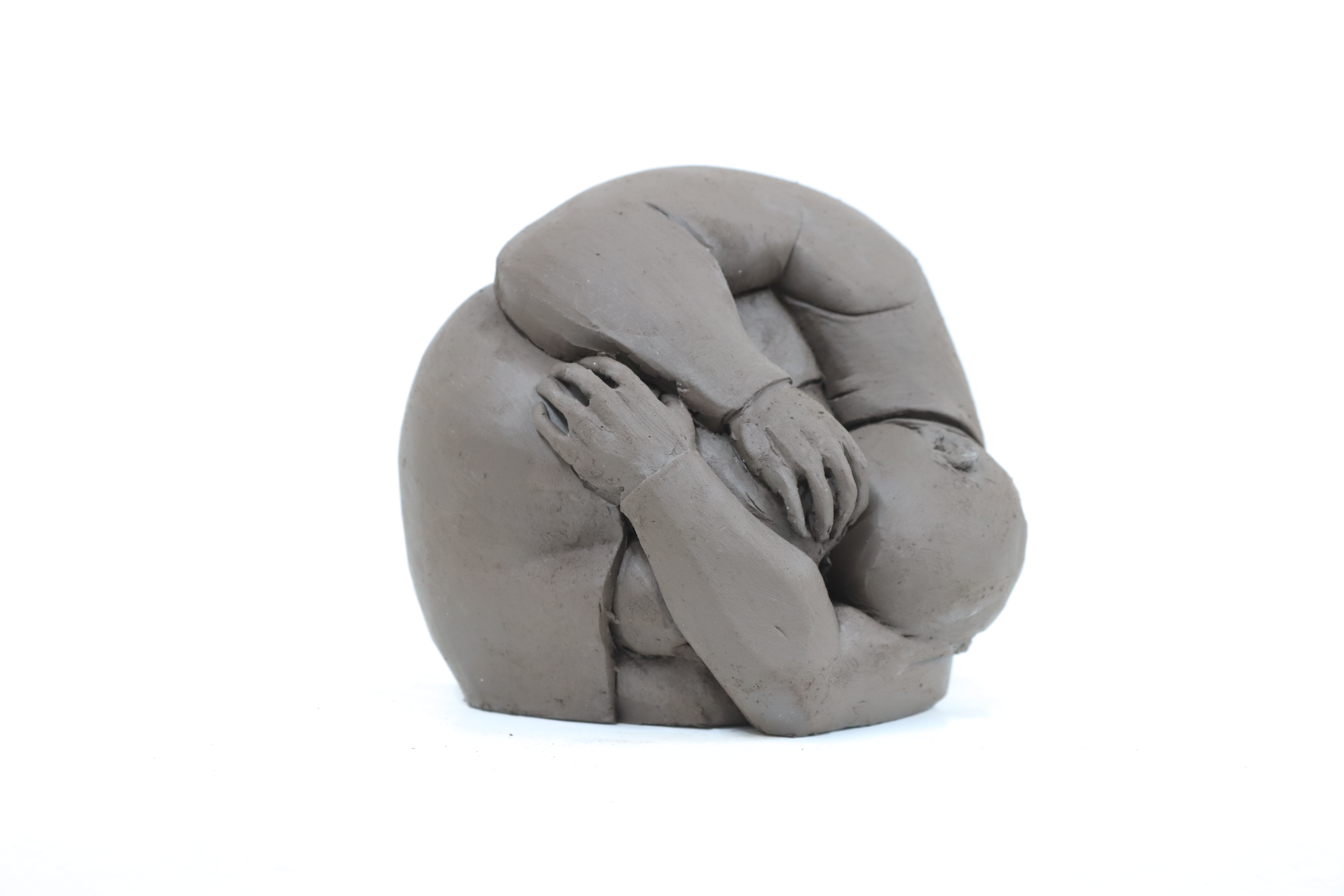

We worked intensively and for a long time, preparing and coordinating with the families of the detainees to involve them in the event. It was a difficult mission, equal to the sense of betrayal they experience on all levels. I wanted them to feel that we share the same fate. I am not only an artist but also a former detainee; I have friends who are still detained, and I have previously created works titled "Compressed" in France about the experience of detention.

My primary goal in participating was to highlight the suffering of the families of the forcibly disappeared through an artistic display that would attract international media attention, especially given the declining global interest in our cause.

What do you aim to convey by destroying it? A reminder of the fragility of dictators, of the United Nations’ inability to do anything for the detainees?

When I began to smash the statue, the temperature was very high in Geneva. The artwork had dried intensely, and as the statue collapsed like a crumbling building, it resembled the United Nations and the regime— a massive structure falling with a strike from a small hammer. It was an expression of anger.

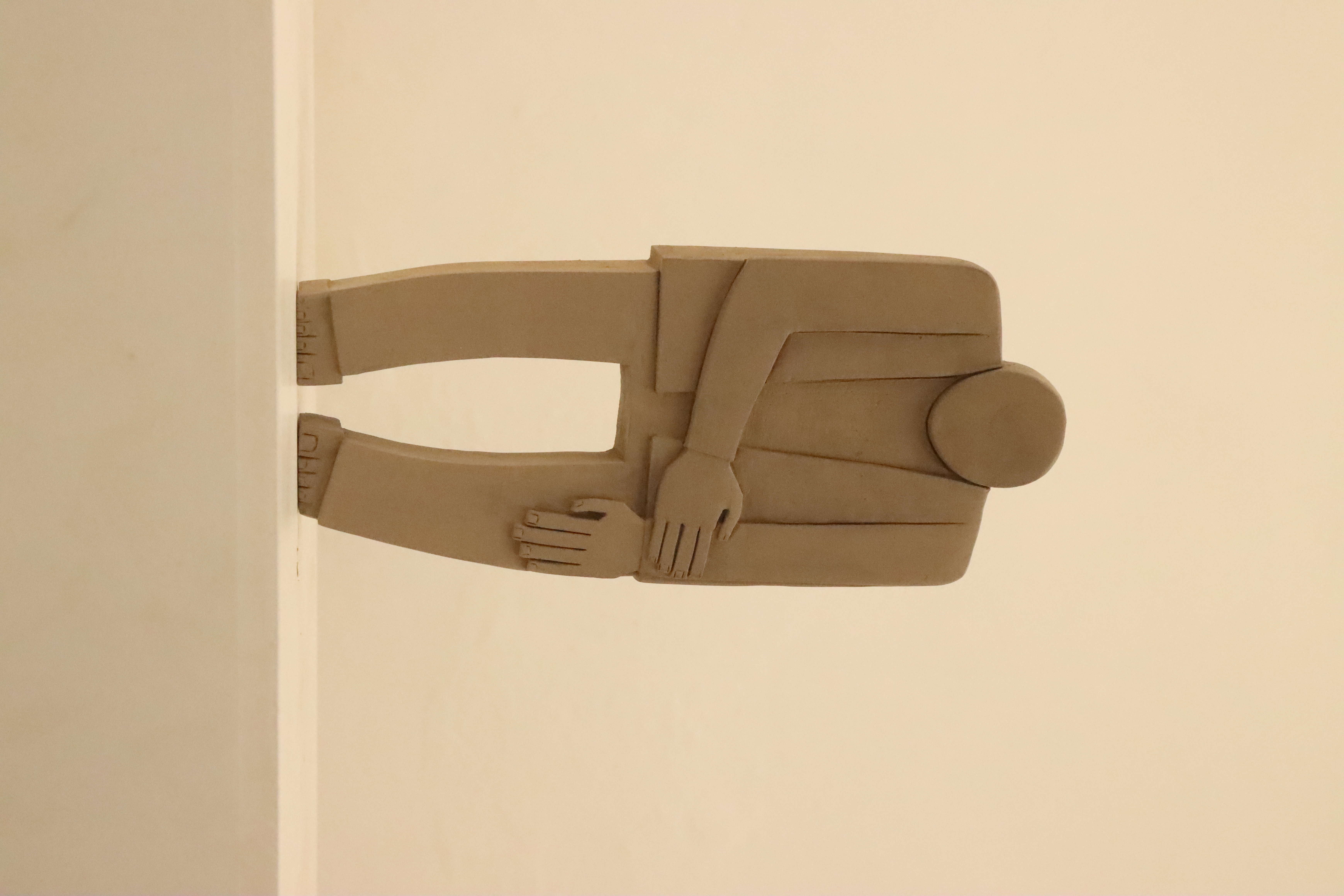

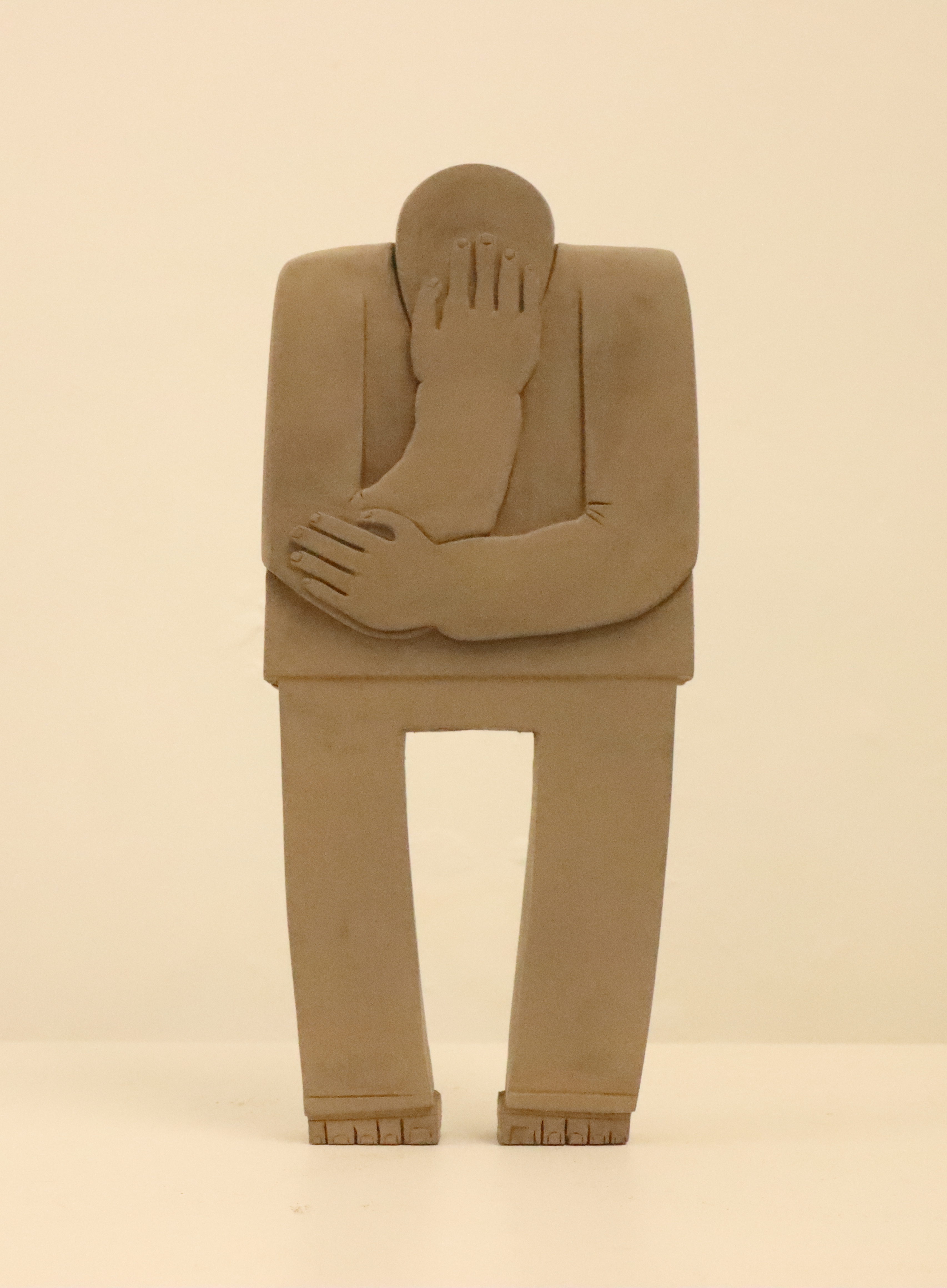

The theme of the "Man of Power," in its broadest sense, preoccupies me, and this is reflected in much of my work. When Europeans see the statue, they say it doesn’t resemble Bashar al-Assad. I explain to them that my work doesn’t address only the Syrian issue; the statue embodies Assad or any dictator, or the regime as a whole in Syria, or anywhere in the world, or any employer figure. And at the top of the hierarchy, there is the global system, the United Nations. I believe that Bashar al-Assad’s regime and others like it are products of a global system—a system that exists but is weak, yet you still face it feeling powerless. In my work, you’ll find figures that lean toward the ground, with no legs or arms, faces eroded but still present. And this raises my question: how can such a person or system continue to exist?

We saw the destruction of statues of Hafez al-Assad and his family during the revolution in Syria, as you know, but Assad is still in power. For those watching the destruction of your statue, it seems like a desperate cry, "Why won’t it fall? Let it fall!" Does this destruction also reflect frustration and despair, given that the fragile dictator remains on his throne, with no tangible progress on the fate of the forcibly disappeared?

Yes, that was one of the many thoughts crossing my mind as I destroyed the statue—what’s the point? What am I achieving now? But in the presence of the families of detainees and the forcibly disappeared, my priority was to draw attention to the detainees’ cause and the potential of art to achieve this in societies that respect freedom of expression, where artists and intellectuals have strong, influential voices. The preparation and execution of the event was a challenging journey, both logistically and psychologically. This is evident in the photos of the performance. I was surrounded by a group of friends (Jalal Al-Tawil, Dounia Al-Dahan, and Charbel Kanoun). We all collaborated to bring this project to life. The statue, made of wood, foam, and plaster, was smashed to a pile of debris in a well-known tourist destination in Geneva, near the famous Broken Chair sculpture.

Those who follow your work will notice your long-standing focus on the theme of the "Man of Power"?

Yes, I began this project in 2007—the man seated on a chair. When I started studying sculpture, I encountered skeptical questions from those around me about how I would react, for example, if asked to create a statue of Hafez al-Assad. This was especially relevant because the two most prolific sculptors of these statues came from Masyaf, my hometown. Would I join them and go into statue-making? There wasn’t much encouragement for my choice of this field. So, I began working on the subject of the "Man of Power" seated in his familiar position on the chair, depicting him in a satirical way. It was a way of symbolically getting back at him, making holes in every detail of his body. I sometimes saw him as a sponge, with the holes at other times representing hope—that these gaps were signs of his decay, his eventual collapse.

“The theme of the "Man of Power," in its broadest sense, preoccupies me, and this is reflected in much of my work.”

Before studying at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Damascus, I worked in set design for theater and television, especially for TV series production. I chose sculpture as a major, thinking it wouldn’t demand much of my time and would allow me to continue working in television. Later, my connection with sculpture deepened, especially during the revolution.

In 2007, I worked on my graduation project titled "Waiting," around the same time as the TV series "Waiting" was being aired. I had gotten to know the show’s writer, Najeeb Nseir, and that was the first time I understood how an artwork could address a social issue. My project reflected the country’s state at the time; everyone was in a state of waiting. It featured human figures in different postures, each conveying a sense of anticipation.

In the final week of working on the project, I felt something was missing, so I created "The King of the Waiting," as a symbol of the one who keeps all these people waiting.

After I graduated, the college administration organized an exhibition for the graduates, and we were told that Asma al-Assad would visit. To our surprise, Bashar al-Assad and Asma showed up. When they reached my work during their tour, I sensed discomfort on Bashar’s face. He couldn’t interact with me the way he did with the others, especially when he quickly understood the message of my work. That day was a turning point in my life because the subject of my work saw it firsthand. I realized the power of art to make an impact. From that moment, I continued to work in television until 2011, but sculpture had captured my focus.

How did the revolution impact your work, and what were you working on until you had to flee Syria?

My early attempts at political themes were relatively limited, but my true connection with sculpture deepened with the revolution, which was a monumental turning point. The waiting figures in my collection seemed to come to life, and my last piece from the "Waiting" series was "We Will Awake One Day," which I began in 2010 but never completed. With the revolution, we were no longer waiting—people had started to move.

I moved beyond "Waiting" and created a pivotal work with clay sculptures titled "The Free of the Studio." During that period, we witnessed many protests, and I imagined the statues joining the demonstrations as well. I shared the work on social media with a short text, and it quickly gained traction, resonating with people based on the feedback I received. I continued to create works that reflected the public spirit, such as "I Announce My Defection," "Died of Cold," and "King of Boxes."

“Bashar al-Assad's regime and others like it are products of a global system—a system that exists but is weak, yet you still face it feeling powerless.”

And before that, I had become part of the Al-Bustan project, which was founded by the artist Fares Helou in 2007 and developed until 2011 as both a space and an idea. I became responsible for it after Fares had to stay outside Syria. We dreamed that the revolution would succeed, and we would celebrate that in Al-Bustan. The project's nature wasn't clear to the regime before the revolution until Fares publicly supported it. Many who were part of the Al-Bustan project disappeared, like the screenwriter Adnan Al-Zaraei, and others like Imad Saasaa, Mohammad Derki, and Mohammad Latouf.

In mid-2013, while in my studio and residence at Al-Bustan in the Jerash orchards, I was injured due to a helicopter bombing. I was taken to Ibn Al-Nafis Hospital, where I was immediately labeled as a Free Syrian Army fighter from the Razi orchards and treated as a terrorist. I had been evading compulsory military service since 2007. I remained in the hospital's prison for ten days before being transferred to Al-Qaboun prison, then to the Investigation Branch and military police, where I spent around 45 days in mid-2013. It was an incredibly violent period—prisoners were packed into cells, and many died there. Shortly after, they sent me directly to the army. I stayed there for two months before escaping.

You spent a considerable period in Lebanon, where you created many works but had to destroy them before leaving for France due to potential repercussions. In media statements, you’ve said you comfort yourself by believing they "fulfilled their spatial and temporal function." Do you sculpt for the present or the future? Do you express and react to reality or document it?

As a sculptor in this era, I feel a responsibility to consider what I can convey through my medium. For example, I try to clarify why I am here, in Europe, through sculpture. At the same time, although to a lesser extent, I aim to document this period.

Mohamad Al Roumi: Cinema is always necessary

11 March 2022

I began destroying my works back in Syria. Between 2011 and 2013, I created around 15 clay sculptures at Al-Bustan, then destroyed what remained after taking photos and posting them on my personal page. I wanted to avoid the possibility of being arrested, imagining that security forces might break them over my head, quite literally. After my friends were detained, I deleted my Facebook account to avoid potential repercussions during interrogations.

After arriving in Lebanon, I created the page "Clay and Knife," which became my sole outlet for expression during a time when I had to remain hidden. I considered it a means to stay minimally connected with what was happening in Syria and with the people there. My works had a satirical tone more than being sculptural pieces, reflecting the period when elections were held in Syria. Despite being in Beirut, my conditions were far from comfortable; I was fleeing compulsory military service, lacked legal documents or residency in Lebanon, lived in isolation, met no one, and relied solely on the internet for communication. I wasn’t stable enough to work normally, exhibit my art, or preserve it. In fact, I did some work in Beirut and was defrauded by a Syrian person, but I was unable to take action against him, given my fragile legal situation.

My experience in Beirut was harsh and contrary to the romanticized image I had of the city, influenced by my admiration for its artists. I stayed there for a year and a half, hoping to remain close to Syria, but the overall situation became unbearable. I ended up destroying my pieces out of frustration as I didn’t know where to leave them when I eventually left for France.

Later, after arriving in France, I made sure to work with bronze in my pieces and began to think more about preserving these works. My art sometimes revolves around documenting a single day, as with “Here is Aleppo,” or a major event, such as “Here is My Heart,” which captures the destruction in Damascus’s Ghouta, and is currently exhibited at the Louvre-Lens Museum. This piece is a historical document, more than just art, because we are in a narrative struggle. I felt compelled to narrate the story from our perspective.

In France, you started working on pieces under the title “Compressed.” Did the harsh experience of detention make you more prolific after your release, crystallizing ideas you may have imagined while imprisoned?

My presence in France has provided me with a minimal level of stability; I have a studio, and I enjoy freedom, which is the most important thing. Certainly, the experience of imprisonment, which I lived through to its extreme, was brutal and affected my work one way or another. The possibility of death hovered over me every day back then due to my previous injuries and the intensity of the violence in detention. When I was released, I felt an even greater responsibility, as a broad question kept turning in my head during my imprisonment: what are others doing for me? And I believe thousands of detainees are asking that same question today, “What are they doing for us?”

Sometimes I’m overwhelmed by questions about what I’m doing and why I don’t just focus on my own life. But I don’t see myself as an artist, nor do I think of myself as having the luxury to choose whether or not to speak about my country. I see myself only as Khaled who, even if he were a chef, would work on culinary projects that tell his country’s story in some way. It’s a responsibility, not a desire.

I’m afraid that one day a friend might come out of detention and ask, “What did you do for us?” The “story” in Syria isn’t over for me. I took part in a revolution, fully aware of the regime’s extreme brutality and the high cost it would demand. But I can’t say that I tried for a time and now can’t continue. There are many people like me, who still hold onto a glimmer of hope.

Going back to your work “Here Is My Heart”, which you mentioned earlier, what motivated you to start creating it? Where has its journey in exhibitions taken it, and do you plan to continue sculpting pieces around the theme of destruction?

When Aleppo fell into the hands of the Syrian regime and its allies, I created a piece titled “Here is Aleppo”, depicting a massacre. Then, when Damascus’s Ghouta fell at the end of 2018, I felt compelled to create another piece. It was an event too enormous to process, and I felt the urge to express it. Initially, I considered creating something similar to “Here is Aleppo”, but then I decided that it should be different, with a different purpose.

As we know, the regime destroyed half of Hama in the 1980s, erasing all traces of the destruction in a short time. Similarly, what happened in Damascus’s Ghouta in 2018 left a profound impact on me. I feared that this regime—so skilled at erasing its traces—might eventually erase what it did in Ghouta. This is when I began working on “Here is My Heart,” without any set plan or reference to photos or videos. I visualized the neighborhood in every detail. I didn’t want to replicate an actual neighborhood; instead, I relied on my imagination and memories of Ghouta and Syrian life in general.

I envisioned going to Syria and bringing a piece of it to France, allowing people to see what war truly means—how an entire neighborhood can be destroyed and what drives millions of people to come to Europe, including an elderly woman in her seventies, who certainly doesn’t intend to take jobs away from people in the West.

I tell visitors that I haven’t depicted the destruction in its utmost brutality; the devastation is far greater than that. However, I have sought to respect the smallest details in each home—furniture, decorations, photographs, and all elements related to daily life.

The work is presented in a unique way at exhibitions, in a relatively dark room illuminated by soft light, because the piece portrays the place on a moonlit summer night. Through it, I present our “neighborhood” culture, including the restaurants and shops where we gather and celebrate our nights. I won’t hide that I sometimes find myself having to answer strange questions from the French, such as, “Are there buildings in Syria? Did you party?”

I sculpt what I experience in reality, following my intuition and instincts, without adhering to a particular methodology or art school. This contrasts with my work in scenography, where I rely on a structured approach. I started working on “Here Is My Heart” at my workspace, which is only two meters by one meter in size. I created a wall of plaster and another wall of clay, then allowed myself the freedom to proceed without a plan. I somewhat lost control over what I was creating, ending up with a six-meter work consisting of three levels. I learned a lot during the three years I spent on the sculpture. During that time, French visitors would come and talk about seeing something similar on television, only to notice upon closer inspection of the sculpture the presence of books by Mahmoud Darwish, Abdul Rahman Munif, and Gabriel García Márquez, along with an elderly woman sitting at a door, a bed... It’s a different approach to depicting reality in Syria, far removed from the images that have taken on a consumable form in the daily context of repetitive destruction scenes.

Everything in the work is imagined. However, I was born and spent part of my childhood and youth in Damascus, and I began building the sculpture in the way that informal buildings are constructed there, without referring to an architect or following traditional building methods. In the later stages of the work, I envisioned real families living in each house of the sculpture, including, for example, Ali Mustafa, Abu Samad, the father of activist Wafa Mustafa, who has been forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime for over 11 years. Abu Samad played a significant role in raising entire generations in Masyaf. Personally, he always encouraged me to complete my studies and pursue a degree in fine arts. I took his picture and the pictures of his family and imagined what their home looked like. Similarly, I worked on imagining the home of the forcibly disappeared detainee Rania Al-Abbasi and her family, as well as the other houses and their residents.

“I’m afraid that one day a friend might come out of detention and ask, “What did you do for us?” The “story” in Syria isn’t over for me. I took part in a revolution, fully aware of the regime’s extreme brutality and the high cost it would demand. But I can’t say that I tried for a time and now can’t continue. There are many people like me, who still hold onto a glimmer of hope.”

The work was first exhibited at what is called the "Cité des Arts Internationale" in Paris in an exhibition organized by the "Open Doors Association," then it was acquired by an art institution and donated to the Mucem Museum in Marseille, where it became part of the French national collection. I did not give it to a single institution but rather to a team made up of several people and organizations from different countries, whom I trust and love working with. It has been exhibited in three museums over the past three years and is currently at the Louvre Lens Museum.

What distinguishes the work, from my perspective as an artist, is that it is considered an "unfinished work," which means I have the ability to work on it as long as I am alive. Therefore, I have the right to work on or add any new detail in any new museum I go to during the final preparations for the exhibition, allowing me to have a unique experience in the museum that hosts the work. I still generally control the work and the places it is exhibited, as the work has its own story for me, and it means a lot to me and my friends who helped me a great deal in transporting and completing it.

While building it, I imagined where the shell landed and what it destroyed. I design the chair as a carpenter would and then destroy it to make it look as realistic as possible. I think about who the residents of each house are—are they Islamists, leftists, or right wing? It occupied a large space in my studio. I am pleased with the visitors' comments on it and their imagining that it is their neighborhood. It was also my way to realize and understand the destruction that occurred in my country after 2015, especially in Damascus, to which I have a special connection. Thus, the loss of Ghouta and its return to regime control was a tremendous loss for me. I am still occupied with the work today, dedicating the necessary time to it. I am thinking of creating a new work, but with a different purpose related to cinema.

You say that you are still mentally inside Syria, even though you live in France, and you interact with the situation there. Do you face challenges with the stagnation of the Syrian situation?

Our mass migration was not based on a desire; as you know, we were forced into it. I certainly have a problem with the stagnation of the Syrian situation, as do all Syrians who wish to end this nightmare. There are many political initiatives that do not come to fruition, and there is neglect of the Syrian issue by all parties, perhaps most importantly by "us Syrians."

From time to time, I return to the theme of waiting that occupied me before the revolution. The circumstances around us have forced me back to it, but we, who are here abroad, enjoying a space of freedom and safety, must present different propositions related to survival, the future, creating hope, and celebrating love and life. It is a struggle I experience daily in my work; we must continue.

“I feared that this regime—so skilled at erasing its traces—might eventually erase what it did in Ghouta. This is when I began working on “Here is My Heart,” without any set plan or reference to photos or videos.”

This is evident to anyone following your work over the past ten years you have spent in France; it is almost entirely Syrian. Have you tried or thought about engaging with your French surroundings in your work?

I work more with the French than with Arab exhibitions. I have lived in this country for ten years, spending half of my youth here, and I am, of course, concerned about this society, which has become part of my memories. However, I am still preoccupied with the Syrian issue and conveying the Syrian cause to the French context in which I live through my work. I believe that most of what they see in the media regarding Syria is related to jihadists and terrorism, with little coverage of Syrian society or the revolution. The Syrian issue is often framed in terms of the binary between the Assad regime and ISIS. I live a relatively normal life, surrounded by a number of Syrian and French friends, but the social life here is different. Meetings with friends are no longer like those we experienced in Syria.

Who is your audience in the meantime? Do you create works aimed at a European audience or do you address the audience of the revolution?

I think I address both sides. When I create works related to Syria, I try to convey through them to our people in Syria that we have not forgotten them. The messages I receive from Syria, from friends or people I do not know, expressing how my work has affected them, mean a lot to me. However, I have also begun to pay attention to the European audience, because the systems in these countries are what enable dictatorships to continue. It is crucial to raise awareness among this audience about the sensitivity of normalizing relations with the dictatorships in our region.

I think that if I ever return to Syria, I won’t just simply go back and finish my work in France. I will try to benefit our country by forming partnerships with French art organizations, for example, to establish and develop projects in Syria. Therefore, I find my communication and work with the French community beneficial on various levels. I strongly believe in the role of the artist in society.

Regarding your belief in the role of the artist and your focus on the European audience, do you feel that it has become more difficult to influence or perhaps contribute to change in the Syrian situation, as it was before 2014?

The situation is difficult and complex, not only for us Syrians but for the entire Arab region. Nevertheless, I see that if there is to be a genuine contribution to change, it must be distinctly Syrian. I don't think we have the luxury to ponder whether it is worth it or not; we must work and continue building our experiences and knowledge. Change comes through accumulation and belief in your rights and your cause. These are not just slogans; they are realities we grasp by reflecting on the history of people's struggles and conflicts for their freedom and independence. We must continue to work. Therefore, I believe that everyone is obligated to contribute, especially the educated class, which has the privilege of influence, but at the same time bears a greater responsibility.