“How can philosophy become a way of life?” came to mind as I was reading the recent book by the thinker and university professor Hussam al-Din Darwish, published by Mu’minun Bila Hudud under the compelling title “Darwish Between Fate and Destiny”. While reading, I recalled a line written over a century ago by the French poet Verlaine in one of his poems, where he declares, "As for me, I will leave content from a world where action is not the twin of dreams." For poets, a dream is not merely a product of imagination; it is the result of an intricate interaction between imagination, thought, sensation, and feeling.

The book is a collection of dialogues conducted by the Syrian writer and researcher Mohammed Dibo with the Syrian thinker Hussam al-Din Darwish, addressing a range of issues. I will focus on three of them: democracy, secularism, and political Islam, each of which is approached from multiple perspectives, steering clear of ideological debates and sweeping generalizations. This is due in part to the interviewer’s skill in posing questions that stem from a close examination of reality and its complexities, and in part to the intellectual framework of Darwish, who responds with a dialectical approach. He presents an idea, then confronts it with its opposite, producing a third idea that is not merely a synthesis but a transformation of both perspectives. This recalls a concept by the Romanian-French thinker Basarab Nicolescu, which I translate as "the included third within duality," harmonizing with French philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s notion of “oneself as another” from his well-known book bearing that title. Indeed, Hussam al-Din Darwish offers us a model of thought that does not progress in a linear fashion but instead unfolds in a complex, networked way without lapsing into unnecessary complexity. His process is driven by the pursuit of truth and a reluctance to settle into certainty, revealed by his frequent use of probabilistic language: "perhaps," "likely," and "might." Probability, as we know, remains open to multiplicity and the infinite.

Conceptual Foundations

This way of thinking arises from a conceptual framework adopted by the author, which relates to knowledge, language, and philosophy. Human knowledge, in his view, is “necessarily interpretive knowledge,” and because of this, it inherently “includes the concept of multiplicity… (since) every interpretation necessarily affirms the legitimacy of difference” (p. 218).

Revisiting 11th century philosopher-poet Abu Alaa al-Maari, in pictures

30 August 2021

As for language, being a human product that accumulates the knowledge, cultural, and life experiences of its speakers, it is, as he describes, “laden with numerous judgments and evaluations, some of which may not even be consciously considered at the time of use. This is why there is always a surplus of meaning in what we say; our language expresses more than we intend to convey, or even something different from what we intend.” This perspective positions language as preceding thought and grants it independence from the speaker—a view also held by the formalist movement in literary criticism, which shifted the focus in literary history from the author to the text itself. This may be what the French poet Rimbaud meant by “For I is another,” referring to what literary critics call the “writing self”, as distinct from the individual self.

This approach is characterized by its commitment to the right of interpretation, opening up space for multiplicity, discussion, and openness to criticism. It is worth noting in this context that the author adopts a Kantian approach to criticism—one that “establishes the legitimacy of the criticized subject, while also delineating the boundaries of that legitimacy” (p. 259). In other words, it is a dialectical approach that keeps thought in a state of alertness, tension, and evolution.

Philosophical thinking, for Hussam al-Din Darwish, finds its practical expression in embracing intellectual diversity, respecting the right to difference, and upholding dialogue as a means to create more harmonious human societies.

Darwish’s approach to defining philosophy aligns with the intellectual orientation we have noted: “It comprises conflicting perspectives, none of which can exclude any other perspective or deny its right to exist and to defend that existence,” he clarifies, adding, “or at least this is how philosophizing ought to be” (p. 219).

We can assume, then, that philosophical thinking for Hussam al-Din Darwish finds its practical expression in embracing intellectual plurality, respecting the right to difference, and committing to dialogue as a pathway to more harmonious human societies. For him, thought that does not connect to life and contribute to the realization of human dignity through its application becomes a mere elite luxury, or perhaps just a form of amusement. We will attempt to substantiate this assumption by examining the three issues highlighted in the introduction.

First, on Democracy

In line with his general intellectual stance, Darwish adopts a notable definition of democracy as "governance through discussion." He establishes a fundamental criterion for democracy: "the extent to which a system allows for differences, the quality of its management of the conflicts arising from those differences, and how fairly it addresses them" (p. 220).

Undoubtedly, this logic responds to the reality of contemporary human societies, which have largely become culturally, linguistically, and ethnically diverse due to globalization, the ease of movement for people and goods, and waves of displacement and migration. This diversity necessitates wise management of variation and difference. The right to differ is inherently linked to the right to freedom, which is considered foundational to democracy. However, Darwish distinguishes between the rights of groups and the freedoms that democracy should ensure, and the individual’s right to free choice, which is not necessarily guaranteed in democratic systems or in those that claim to be democratic: "There is no meaning to any representation, election, majority, or plurality if the individuals involved are not free" (p. 227). The Lebanese model perhaps exemplifies his viewpoint, as the system of representation guarantees the rights of sects, but this does not extend to individuals due to the reality of tribal, leadership, and sectarian affiliations. A minority of free individuals reject this system, yet their voices hold little weight. It is also worth noting that freedom is a disposition, education, and practice, highlighting the importance of the family, school, and university in cultivating free thought and responsible individuals who exercise their freedom.

For a Secular Interpretation of Prophethood

12 August 2017

The right to freedom is inseparable from the right to equality, or more precisely, from equal opportunities. This prevents individuals with cultural, social, or economic privileges from controlling the freedom of others who do not share such advantages. While it is acknowledged that political and social liberalism is foundational to democracy, economic liberalism can, in fact, lead to the opposite of democracy by facilitating the dominance of those with substantial capital in shaping public opinion through various means, including media and culture. Therefore, Darwish advocates for establishing "a positive dialectic, both theoretically and practically, between freedom, equality, and social justice."

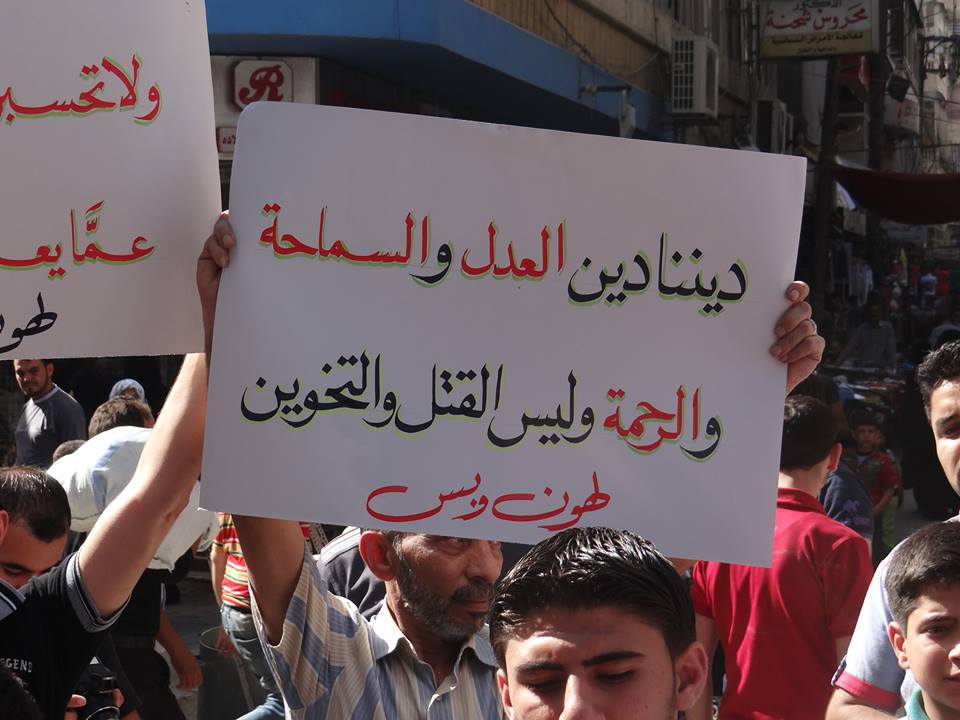

While emphasizing the importance of civil society as a criterion for democracy, Darwish does not spare his criticism of doctrinal parties, particularly in Arab societies. He argues that these parties view citizens as a mass that needs to be "liberated" from "backwardness" and "ignorance," relying on a nationalist "liberation" ideology or an Islamic "da’wah" ideology. He highlights the necessity of distinguishing between liberation and emancipation, or between the passivity of the recipient in the act of liberation and the proactive engagement in the act of emancipation; in liberation, “the people are the object,” while in emancipation, they are “the subject.”

Darwish believes that the ideological burdens carried by these parties constitute one of the many obstacles to democracy, compounded by the "crisis of national identity," the "strong presence of tribal affiliations at the expense of civic affiliations," and the "weakness in civil political culture and experiences." However, in keeping with his usual approach, he prefers not to be dogmatic or absolute in his opinion, allowing room for discussion. He adds, "The existence of any of these obstacles does not aid in the democratic transition, and the absence of them might assist in that transition" (p. 230).

Darwish adopts a notable definition of democracy as "governance through discussion." He establishes a fundamental criterion for democracy: "the extent to which a system allows for differences, the quality of its management of the conflicts arising from those differences, and how fairly it addresses them.

He also does not forget to point out the negative aspects of democracy, where the voice of the ignorant holds the same weight as that of the knowledgeable, allowing individuals to attain power simply by convincing voters, regardless of their actual qualifications, ethics, or ability to bear responsibility. This leads us to conclude that the realization of positive democracy requires political awareness, the ability to form independent opinions, and the application of critical thinking, all of which cannot be achieved without cultivating the mind through education, culture, and the dissemination of knowledge. He acknowledges that democracy "can create an environment conducive to instability when political forces conflict and fail to reach understandings and agreements among themselves," a situation that is indeed evident today in Lebanon.

Nevertheless, democracy remains, in his view, the best model of governance, yet it is in a constant state of evolution, sometimes regressing and then correcting its course depending on circumstances and experiences. The thinker is indeed correct in emphasizing the diversity of democracies; on one hand, he asserts that democracy "does not have solely Greek or European origins but has roots in all civilizations and cultures to the extent that those civilizations or cultures adopted ideas, values, and principles that promote freedoms, pluralism, and consultation" (p. 244). In this way, he successfully removes democracy from the confines of Western centrality, making it at the same time a shared legacy and an available possibility for all peoples, rejecting the notion of cultural exceptions.

Second, on Secularism

The thinker approaches the issue of secularism without simplification or reductionism, examining its relationship with citizenship and democracy, as well as its connection to religion. Secularism is not merely the separation of religion from the state; it encompasses various definitions and takes on different forms depending on the social, political, and cultural contexts.

The first definition Darwish proposes is that secularism is "equality in citizenship, along with all the rights and responsibilities associated with it, regardless of religious affiliations" (p. 268). This definition is non-controversial, as it does not define secularism solely through its relationship with religion but rather through its connection to the foundations of democracy.

Regarding his conception of the relationship between the state and religion within secularism, he believes that it should not be exclusionary nor integrative (in the sense of the state exploiting religion or vice versa). Instead, it should be characterized by the neutrality of the state toward religious beliefs and the non-preference of one religion over another in pluralistic societies. He states, "Neutrality and non-preference do not necessitate a complete separation between religion and the state; the state can assist the religious in organizing their affairs without undermining citizenship equality" (p. 269), as is the case in Germany and Britain.

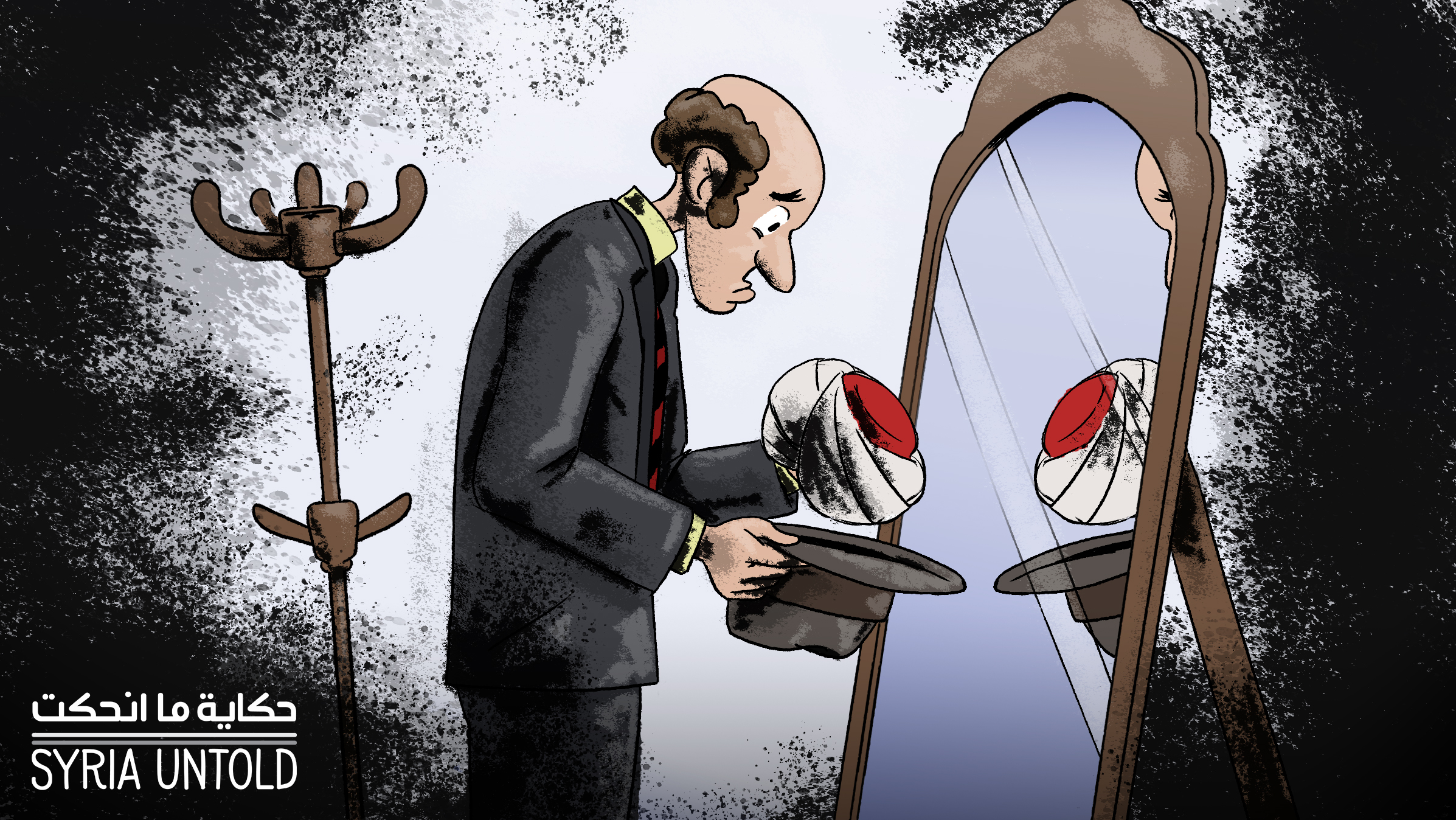

From his perspective, secularism does not necessitate the separation of religion from politics but rather "the separation of religion from sovereignty." This is a realistic and necessary proposition in our Arab societies, where religion is perhaps the most significant element of identity, which aids the ambitions of its proponents to dominate and exert control, especially in light of the current identity crisis.

Secularism does not necessitate the separation of religion from politics but rather "the separation of religion from sovereignty." This is a realistic and necessary proposition in our Arab societies, where religion is perhaps the most significant element of identity.

Based on this, he adopts a critical stance toward French secularism, or "laïcité," which advocates for the exclusion of religion from the public sphere (p. 272). While France has succeeded in this throughout its contemporary history, it now faces challenges as Islam has become a fundamental component of its identity due to the increasing number of Muslim citizens who struggle to accept this exclusion.

The pragmatic approach he takes in examining the relationship between secularism and religion through a dialectical lens provides a way to move beyond this exclusionary tendency and establish more harmonious societies. He argues, "In contrast to the dualistic view of the relationship between the religious and the secular, I see a preference for considering the interplay between the two, where one can talk about secularism or the secular within religion itself, and where religion can be present or can be brought into the heart of secular society... It can even serve as one of the moral and spiritual sources beneficial to the state and its political system and political actors in general" (p. 270). This perspective naturally leads us to the issue of political Islam and his stance toward it.

Third, on Political Islam

What distinguishes Hussam al-Din Darwish's positions on the issues he addresses in general, and on political Islam in particular, is the scientific neutrality that objectively examines reality and attempts to grasp its complexities and analyze them through dialectical reasoning, leading to an understanding and formulation of an opinion on the matter. Thus, he proposes a precise definition of political Islam that avoids ambiguity: it is "the clear or explicit, organized, and fundamental reliance on Islam in the practice of politics and/or its theorization concerning issues related to governance and power within the state's institutions and its public sphere" (p. 276).

He differentiates between political Islam that seeks to achieve its goals through peaceful political means, and thus can align with democracy, and "jihadist Islam," which employs violence and poses a threat to the peace of societies and states. He emphasizes the importance of the reciprocal relationship between political Islam and the state in Arab and Islamic societies, which can be positive when the state acknowledges the legitimacy of political Islam on one hand, and when Islamic parties recognize "the legitimacy of the state" on the other. This recognition would entail a shift from the concept of "the Islamic nation" to that of a democratic civil state based on the principles of citizenship, the rule of law, and respect for pluralism and individual freedoms (p. 279). In such a scenario, political Islam becomes a part of the democratic practice.

However, this relationship can also be negatively exclusionary, transforming political Islam into jihadist Islam that adopts violence to seize power. While this distinction is theoretically valid, it may not hold true in practice on the ground, where we observe the phenomenon of the "Islamization" of societies, the diminishing role of civil society, restrictions on individual freedoms, and the suppression of secular currents or ideas—even in countries where political Islam has attained power through peaceful means, as seen in Gaza under Hamas rule. This situation may arise from factors not only related to the nature of political Islam but also to a wounded identity seeking refuge in religion.

Hussam al-Din Darwish distinguishes between political Islam, which seeks to achieve its goals through peaceful political means and can thus align with democracy, and "jihadist Islam," which employs violence and poses a threat to the peace of societies and states.

In his analysis of the relationship between religion and the state, or between political Islam and the ruling system, the author differentiates between "official political Islam," which benefits from the complicity of the regime that, in turn, utilizes it to achieve its own interests, and "oppositional political Islam," which the political system and "secularists" agree to combat, even if that comes at the expense of democracy.

It becomes clear, then, that Hussam al-Din Darwish approaches his subjects from both a comprehensive and detailed analytical perspective, distancing himself from extreme positions and biased opinions. This aligns with his cultural convictions and ethical principles, which are founded on the belief in the primacy of the human being, the relativity of human truths, respect for others and their right to differ, rejection of singularities and binaries, and acknowledgment of diversity and pluralism as essential components of contemporary societies. Perhaps the primary characteristic of his worldview is that he views it through multiple lenses, encompassing its complexities and seeking to dismantle them through understanding, interpretation, and translation, relying on his proficiency in hermeneutics. Undoubtedly, the dialogues contained in this book contribute to deepening our understanding of pressing issues that confront the Arab reader and assist us in addressing them, reaffirming once again that Arab thought is still very much alive.