Security and intelligence systems, known for their bureaucracy and strict organization, take every possibility into account—except the scenario of their own downfall and how to manage it. This scenario seems beyond their imagination, leaving them forced to abandon the documents they had meticulously recorded and the prisons they had built. This is exactly what a team of journalists, researchers, and activists encountered as ISIS gradually crumbled in Syria and Iraq under the pressure of an international coalition led by the United States. While battles were still raging, they attempted to access the numerous prisons of the organization in search of friends and colleagues who had been forcibly disappeared. Instead, they were met with an enormous trove of electronic and paper data, including 70,000 documents, which they managed to smuggle out of the country.

At the beginning of November, the team officially launched an interactive digital museum for the public under the name "ISIS Prisons Museum." It offers a sample of the information and documents they possess, as well as related investigations into the organization's crimes.

We met with the museum's director, journalist Amer Matar, for this interview about the establishment of the museum, how they handle the personal data it contains, and their goals for this initiative.

You began working on the project to gather information about ISIS prisons in 2017. How did it all start, and what motivated you to share your data with the public?

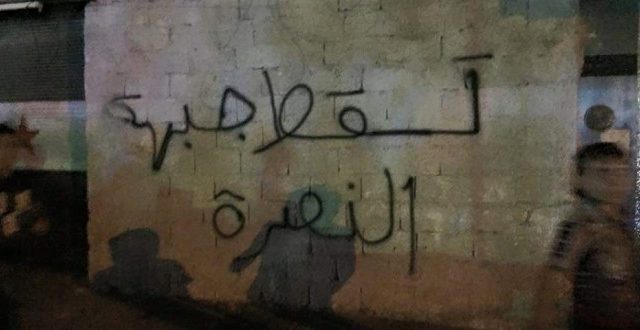

When we started working in 2017, we were not thinking about creating a museum. We were simply searching for missing journalists, our colleagues at Al-Share' Media Foundation. As ISIS's influence started to recede from its controlled areas in Syria and Iraq, we, as journalists, had the opportunity to enter these places, film them, and discover what was inside these prisons and secret buildings where the organization had detained thousands of people. While exploring these sites, we began to find thousands of the organization’s documents, as well as thousands of names, stories, and phrases written on the walls by former detainees. This made us feel a sense of responsibility, as we realized we had extremely important information and documents concerning tens of thousands of people.

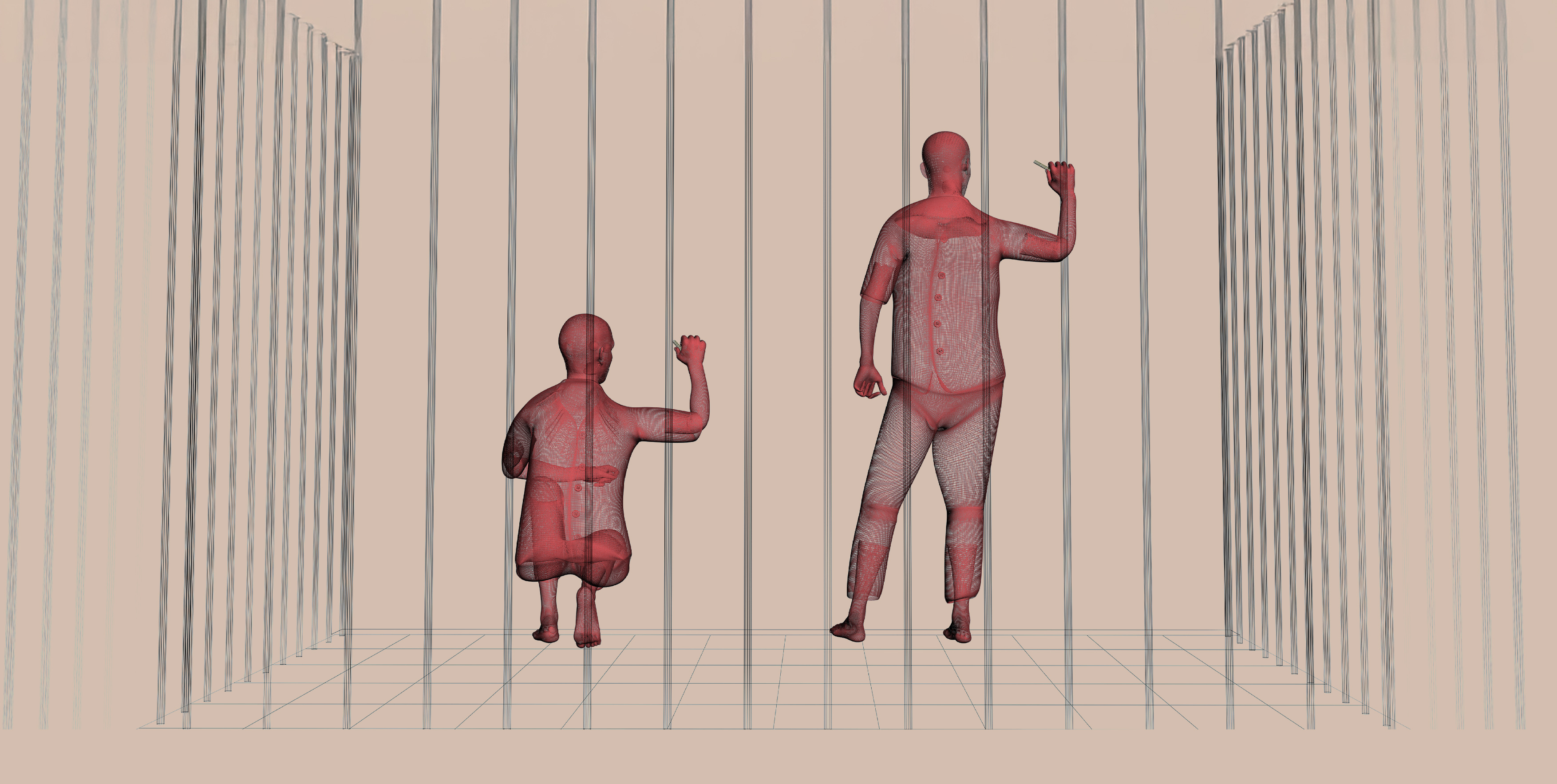

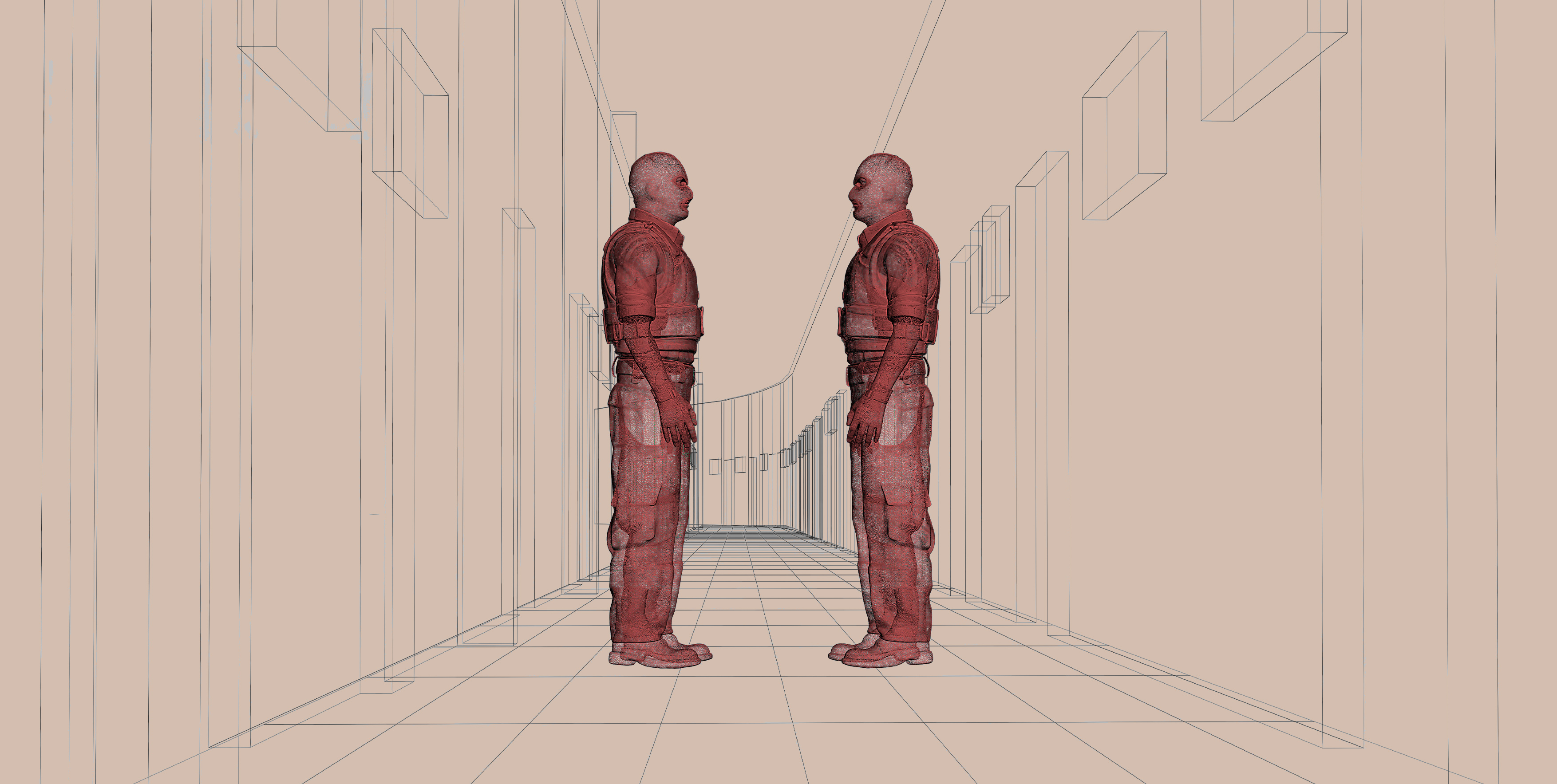

Most of ISIS's prisons were originally schools, private homes, hospitals, and shops. After the fall of the organization, the new controlling forces converted these locations back into detention centers, or the original homeowners returned to the properties that ISIS had turned into prisons. Changes began to affect some of these buildings. It was at this point that we started thinking about how to preserve these sites as historical records of our country, revealing how these buildings were transformed into some of the most horrific prisons. We considered documenting them in a 3D format, and then we continued with our work.

The first phase was focused on locating the prisons and then trying to identify their purposes. There were security prisons, Hisbah prisons, and Islamic courts. This phase was long, complex, and extremely dangerous, primarily because many of the buildings were mined. It was incredibly challenging to enter a place without knowing if it was loaded with explosives or not. In 2017 and the years that followed, thousands of people were killed by landmines left behind by ISIS. For instance, we were unable to enter the Children's Hospital in Raqqa, where we knew there was a prison inside, because it was heavily mined. There were instances when we entered buildings without realizing they had been used as prisons, until we began identifying them by examining the type of doors, windows, fortifications, and what was left on the walls.

Going back to your question, when we discovered the documents, our goal was to document this period in history. We need to understand what happened in our country, what its people experienced, and to study the brutality we are going through—its causes and origins. We are not the first to do this; there are museums about the Stasi in East Germany, Nazi history, and the Red Security Museum in Iraqi Kurdistan, which was a prison during Saddam Hussein's era.

Our work involves comparing different prison systems and laws, examining the tools of torture, the logic behind interrogations, and the structure of the prisons—some of which date back to the Baath regimes in Syria and Iraq, or even to Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, and Camp Bucca. I believe that brutality is interconnected worldwide; each new cycle of violence is built upon previous cycles of violence.

This means you were worried that in the next phase, as the organization’s control diminished, its traces would disappear, especially since some of these traces were drawings made by detainees on the walls, due to civilians returning to their homes that had been turned into prisons.

Yes. It was a race against time. The vast majority of the prisons we found and documented no longer exist. But we were fortunate in anticipating the actions of the community and those taken by the forces controlling different areas in Iraq and Syria. There were different systems and communities trying to return and coexist with what had happened. For example, the Burj prison in the town of Tabqa, which was originally a government building, returned to being so. The same applies to the Muawiya School in Raqqa and the Qaimaqam building in Mosul. The Juvenile Detention Center in Mosul also reverted to being a prison again.

To what extent were the controlling parties on the ground cooperative with you?

Given that all the forces controlling the area were fighting ISIS, they did not have a problem in principle with documenting the prisons. This had a positive effect on our work, as we were able to access places that were not available to the public. However, our work was not without significant challenges. It took us years of coordination and sometimes obtaining approvals, and our teams were sometimes forced to stay in an area for up to six months due to renewed clashes and changes in the forces controlling the region. And as you know, our team working in areas controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces, for example, cannot operate in Turkish-controlled areas as well. Our team in the Sinjar region was working in an area controlled by a group of forces that were partly allied and partly in conflict. Some of our teams faced harassment depending on where they were operating. Despite all of that, there was some level of cooperation. There were areas we couldn’t approach, such as those controlled by the Syrian regime, like Deir ez-Zor and Palmyra, which contained many ISIS prisons.

Have you considered organizing an event related to the museum on the ground in Syria and Iraq?

We tried, in one way or another, to turn the Juvenile Detention Center, one of the most notorious ISIS prisons in Mosul, into a museum. This prison has a long history that saw various regimes and forces of control, so we are dealing with different layers of imprisonment. However, the authorities rejected this, arguing that they wanted to forget what happened. We dream of turning the Al-Mahlab prison in Raqqa into a museum, for example, as it is one of the few prisons that still exist and has not been changed by the local administration. But the problem lies in security concerns, as the organization is still carrying out limited attacks in the region, despite its diminished control there. Therefore, we think about the safety of our team and visitors, as well as the possibility of the site being attacked by the organization if it were converted into a museum. So, we have ideas, but they are postponed for reasons beyond our control.

We want to make the data available for research purposes and provide information that could help uncover the fates of the thousands of missing people in ISIS prisons, in service to society, which we consider our primary goal.

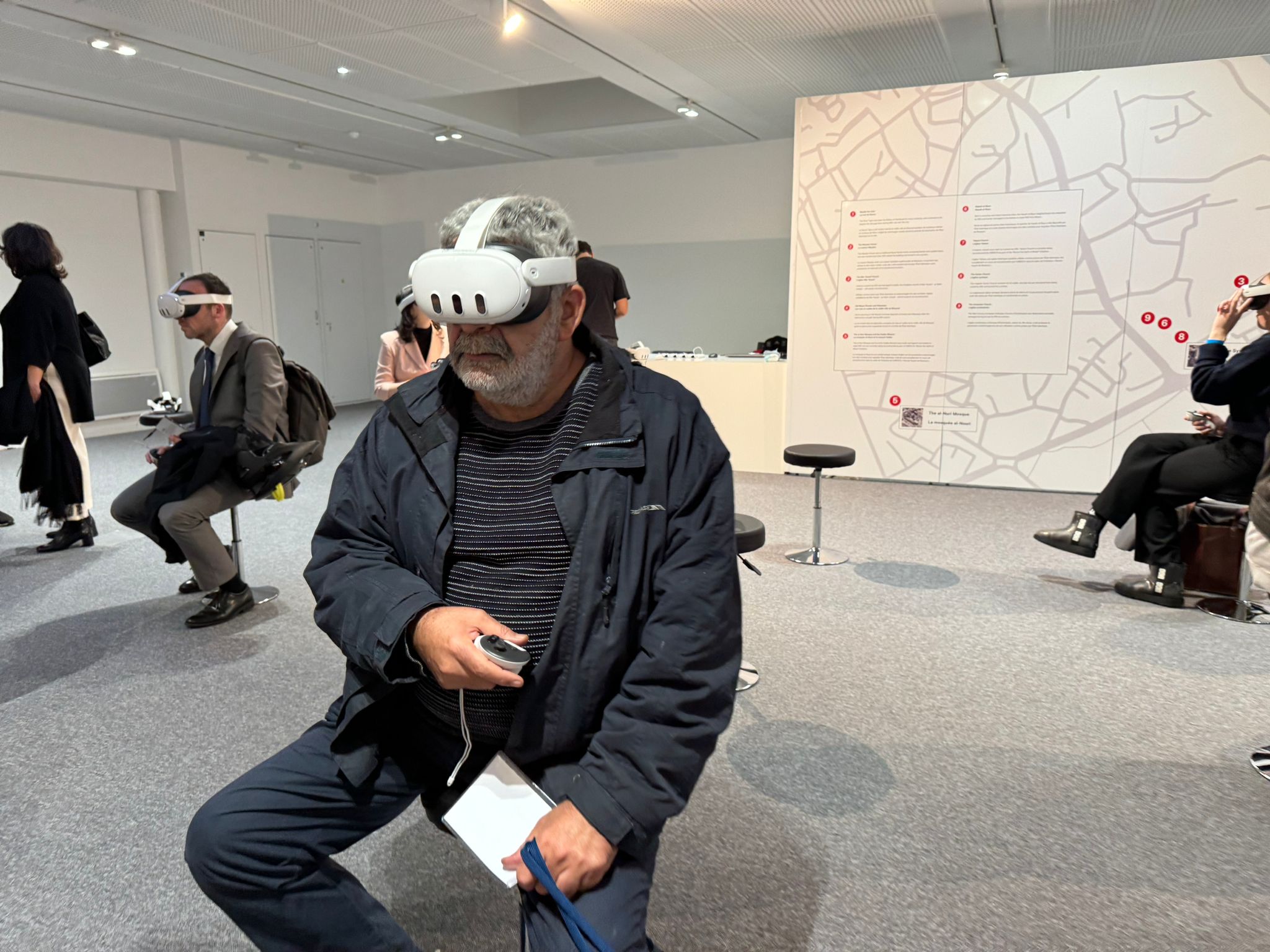

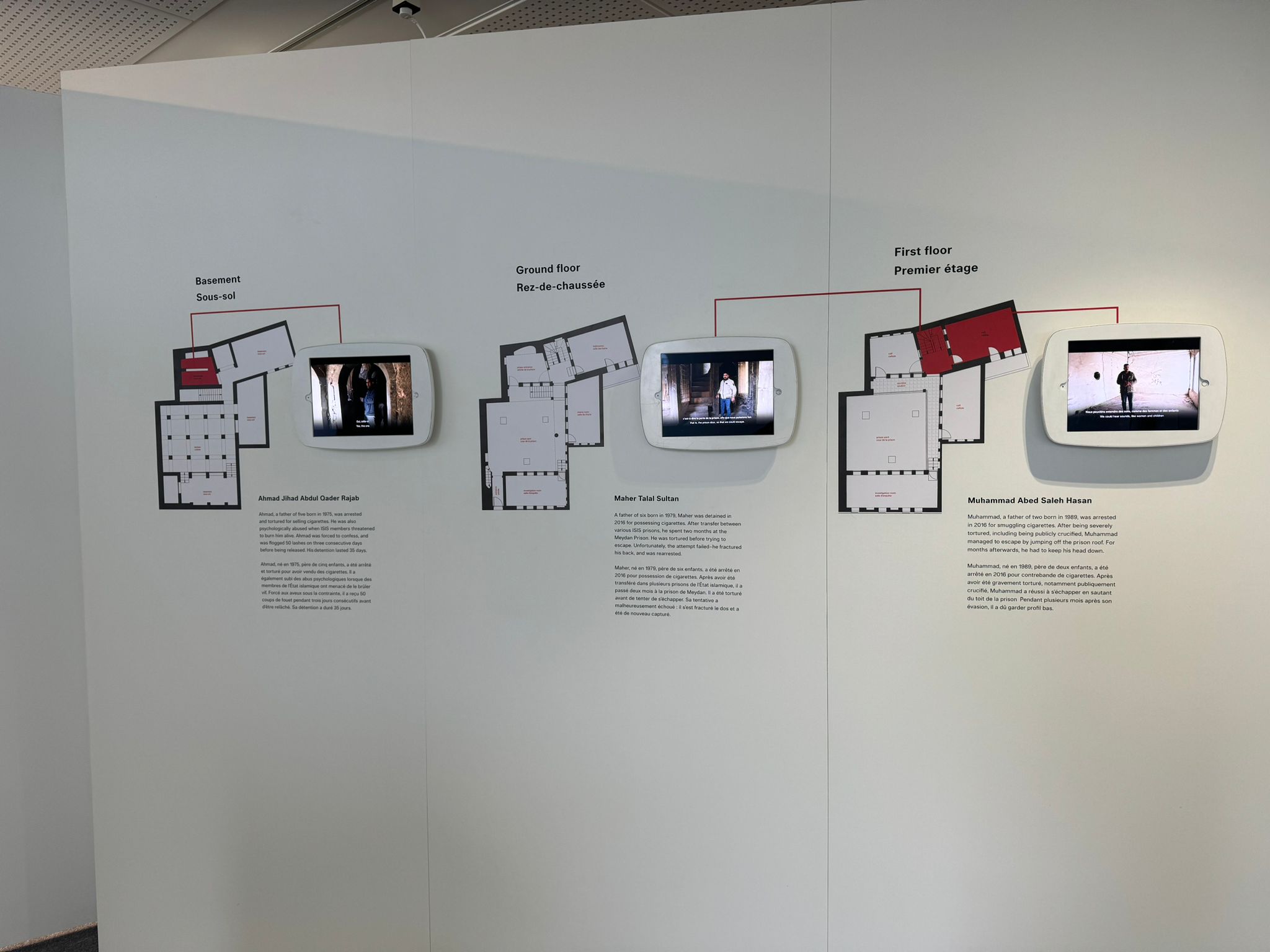

Our virtual museum was launched in early November at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. To mark this occasion, we will hold an exhibition in one of the venue’s largest halls, focusing on Old Mosul, titled "Three Walls", symbolizing a destroyed or incomplete room. ISIS had converted most of the old houses in Mosul into security and military headquarters as well as courts. These were destroyed during the war, with many civilians killed as a result of ISIS actions and the conflict against ISIS. Visitors will have the opportunity to explore Old Mosul and witness the devastation through a 3D version of the city, hearing testimonies about what happened and learning about its architectural history. We have focused on two buildings: the Syriac Church, which was turned into a prison, and a house in the Midan area, which was converted into a prison for the Hisbah (morality police). The exhibit tells the story of the layers of the house or prison and the city’s unique architecture as a whole. It also features the Al-Nuri Mosque, from whose pulpit ISIS declared its so-called caliphate.

What are the technologies used in the virtual exhibition?

What is displayed on the website's interface is a small part of what we have built over the past years and what we provide to investigators and researchers. We use what is called a "capture system" that connects the prisons and their guards on one side, and also connects the prisons to the mass graves on the other.

When the Caesar photos were revealed, images of corpses and victim data spread chaotically, violating their dignity on social media. What have you done to ensure that this mistake doesn't repeat? I mean, how are you handling the issue of confidentiality for the individuals whose names appear in the documents, especially on the Jawab platform, which you have not yet launched, dedicated to ISIS detainees?

This is one of the most sensitive aspects of our work, and we try to be cautious and precise in dealing with it. We only publish specific samples of documents that do not contain names. If the document includes names, we do not publish them unless they are redacted. We have thousands of security reports written by individuals about each other, and confidential information related to the personal lives of individuals.

Families will be able to search for the names of their children through search tools and learn information about them, but within a highly precise legal framework. This means that no one will be able to search for any name they want and find documents related to it. Instead, there will be a series of procedures in place to protect the individual concerned, their family, and all the names mentioned in the report.

This issue is highly sensitive, and it could affect the lives of people living in various countries around the world. We want to avoid problems, such as a state authority misinterpreting a report and taking actions against someone whose name appears in it.

Do you expect that what you have will reveal the fates of some of the detainees held by the organization?

To be clear, we will not be the ones issuing death certificates for detainees. We have documents that say, for example, that an execution was carried out against someone for a certain charge, according to these testimonies and fingerprints. However, determining the fate of individuals is extremely complicated. We cannot claim that a document is definitive proof of an execution. I personally know of cases where executions were not carried out despite the signatures of the individuals involved on their death sentences, due to various reasons, such as the area being bombed, or the individuals fleeing, or other reasons related to the logic of the organization. Therefore, we will not publish these documents, but instead, we will contact the families and share the information with them through our legal team, after confirming their kinship via personal documents.

We have a vast number of mass graves in Syria. I believe that revealing the fate of the missing in the future will only be possible through DNA analysis of the remains in those graves. This is also a sensitive issue, as the International Commission on Missing Persons has only worked in specific areas in Iraq.

We will not be the ones issuing death certificates for detainees. We have documents that say, for example, that an execution was carried out against someone for a certain charge, according to these testimonies and fingerprints. However, determining the fate is extremely complicated, and we cannot claim that the document is definitive proof of the execution being carried out.

The New York Times published what they called the ISIS files in 2018, the result of research into around fifteen thousand documents that their correspondent claimed to have obtained in Iraq. Was there any form of cooperation or coordination between you?

We did not cooperate with any external entities for reasons related to the credibility of the information. The documents we relied on were gathered by our own hands from the buildings and headquarters, and we analyzed and verified them. There are several entities around the world that possess documents related to the organization, including international bodies such as UNITAD, the United Nations investigative mission, which completed its work last September. ISIS is an extremely bureaucratic organization, and all of its internal operations are meticulously audited and archived. Therefore, we believe that a large number of armies and intelligence agencies possess documents related to the organization.

Our project was confidential, and we did not communicate with any external entities. During this time, we began receiving requests from well-known international researchers and journalists who wanted to access documents related to specific issues they were investigating. However, we are cautious because the publication of documents in earlier periods, such as after the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime, led to revenge and acts of violence.

ISIS is an extremely bureaucratic organization, and all of its internal operations are meticulously audited and archived. Therefore, we believe that a large number of armies and intelligence agencies possess documents related to the organization.

Our caution stems from the possibility of encountering journalists who may want to use the information for show-off purposes only, which is something we are very far from. We want to make the data available for research purposes and to provide information that may help uncover the fate of the thousands of missing persons in ISIS prisons, for the benefit of the community, which we consider our primary goal. We are not a journalistic entity competing with others to "reveal the hidden," for example.

You say one of your main goals is to preserve evidence for future trials. Have you cooperated with any legal entities so far?

Yes, contributing to the achievement of justice is a major part of our work. We receive requests from courts and prosecutors, and we respond to them with the information we have. We are part of international legal mechanisms for achieving justice.

To what level of confidentiality do the data you have extend? Are we talking about daily security documents, or highly sensitive information, such as details about the organization's collaboration with international entities?

The documents are extremely varied, including paper documents from various departments within the organization, such as the Department of Morality, the judiciary, grievances, and the military. There are also recorded documents, which include investigations and wiretaps recorded by the organization on people. Additionally, there are pictures and videos that were found on the phones and laptops left behind by ISIS members. Some of this material relates to their daily lives and battles. We have gathered thousands of passports and IDs from different places, such as Baghouz, eastern Syria. There are also papers related to strategies for dealing with the community and battles, but I don’t recall reading anything related to the organization’s collaboration with countries, for example.

We believe that every detainee's life is important, but one question that will immediately come to mind for many readers of this interview is: Do the documents include any information about detainees such as Father Paolo or Samar al-Saleh, for example?

A Previously Unpublished Interview with Father Paolo

26 August 2022

Unfortunately, we did not find any documents related to the individuals mentioned, or other detainees, including members of my own family, such as my brother Mohamed Nour.

Finally, who makes up your team, and what are the main materials you plan to publish or events you plan to organize?

Our team today consists of more than 60 people, located in different countries around the world, including journalists (among them Robin Yassin-Kassab, the editor of the English edition), photographers, researchers, architects, legal experts, archivists, database specialists, and digital security experts. The number of team members grew as the project evolved. I initially worked with researchers and photographers, and the team expanded as needed. For example, we later brought in specialists in 3D design, and recently, in organizing exhibitions.

We will regularly publish related files and investigations. The next report will focus on the “Shaitat Massacre” in Syria and will include detailed information about what took place. This will be followed by several reports on the security prisons in Tabqa, Mosul, the Yazidis, and Kobani.

After the Paris exhibition, we plan to hold our next exhibition in Berlin, which will be dedicated to the “Hisbah Office”. We have extensive information about it. The Hisbah Office operated hundreds of prisons where thousands of people were detained and subjected to harsh punishments.