“We had been waiting impatiently for this day—the day this criminal regime would fall, so we could finally say relief has come. Our loved ones have returned. Our loved ones have been released. We wanted to celebrate the release of all the detainees and missing persons, but sadly, our joy was incomplete for many reasons,” says Fadwa Mahmoud, the partner of Syrian opposition figure Abdul Aziz al-Khair and the mother of Maher Tahhan, who has been missing since 2012. She expressed her thoughts in a video message posted on 11 December.

In the message, she laments the chaos caused by families at detention centers and their destruction of critical documents—a tragedy that ultimately harms everyone. While she acknowledges the desperation driving families to seek answers about their loved ones, she sharply criticizes the actions of those sharing detainee-related material on social media. “We are not material for photography and media,” she says, “and you gain fame at the expense of our cause. Have mercy on us!”

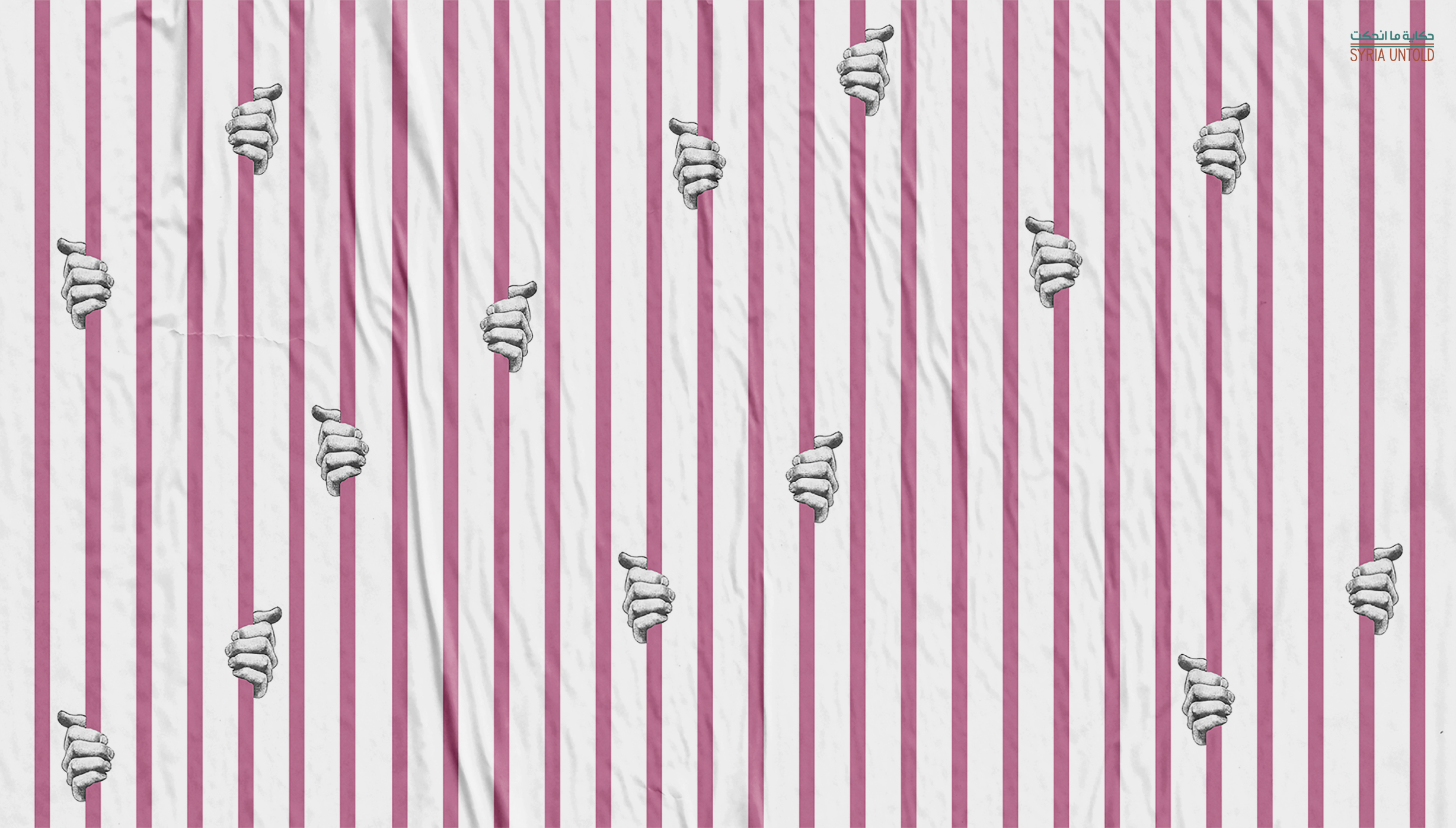

The liberation of Sednaya prison and other detention facilities during the Syrian regime's collapse sent shockwaves through Syrians, particularly the families of detainees. These events revealed that only a small number of those who had disappeared over the preceding decades were freed. Those who emerged suffered from dire health conditions, while the fate of many others remained unknown—perhaps concealed within official records that were severely damaged and scattered across the prison's corners.

As hours turned into days, blame was directed at numerous international and human rights organizations for failing to manage the detainee crisis or safeguard documents that might have held crucial information about their fate. What went wrong?

By engaging with many of these organizations over several days, we attempt here not to fully understand, but to piece together what transpired during the critical hours and days following the regime's fall—moments that were crucial for uncovering the fate of the detainees and the forcibly disappeared in Sednaya prison. Their fates now remain entangled in scattered documents, divided among countless parties.

“Liberating the Neighbors”

Before sunset on 7 December, a group of former opposition fighters from the areas of Asal al-Ward, Rankous, and Talfita approached Sednaya prison to assess the extent of its fortifications, according to Diab Seria, a former detainee and director of the Association of Detainees and Missing Persons of Sednaya. He shared these details with Syria Untold.

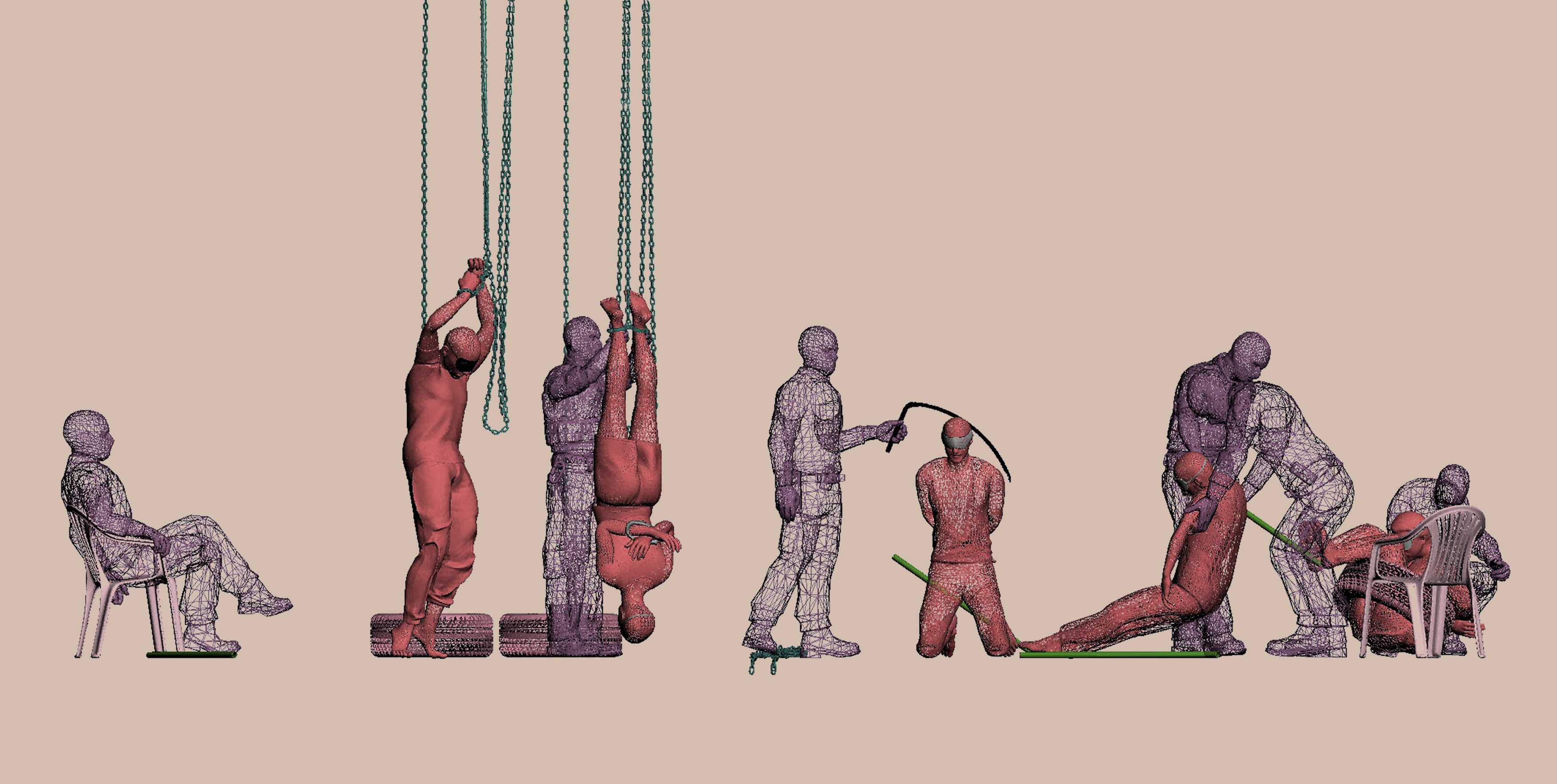

The Virtual ISIS Prisons Museum

15 November 2024

After midnight, the group launched an attempt to storm the prison. They arrived on several motorcycles, armed with light machine guns, and accompanied by a pickup truck equipped with a DShK machine gun. This effort took place before the arrival of the “Deterrence of Aggression” forces, who had started sweeping the city of Homs for regime troops. At the same time, areas in southern Syria were rising up against the regime, according to Diab, who is from the same region, as he explained during a telephone interview.

Diab explains that there was no significant armed confrontation between the two sides, only a brief exchange of fire during which no one was injured. Opposition fighters approached the security detachment stationed at the prison entrance, warning them of the futility of resisting and intimidating them with the potential deadly consequences. They also invoked the possibility of fighters from Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, led by al-Julani, arriving, which persuaded the prison guards to agree to an exit route.

As news of the operation spread, residents from nearby areas like al-Tall and Manin began gathering at the scene. Diab recounts that an intense fear gripped the fighters who had entered the prison to free detainees. They suspected the regime might have prepared counter-scenarios, such as regrouping its forces along the coast for a counterattack or enlisting its Russian allies to bomb Sednaya prison from the air. These concerns made tasks like counting the number of released detainees nearly impossible at that moment.

Diab addresses the rumors about the systematic destruction of evidence, explaining that thieves—commonly referred to as “Shabiha”—from a town near Sednaya (whose name is omitted here to avoid retaliation) entered the detention center intending to steal or loot. The detainees initially mistook them for members of the invading forces or Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, as they were armed with weapons, including bombs, and arrived in vehicles covered in mud. The thieves seized laptops and devices connected to surveillance cameras. However, their actions—setting a fire (which locals extinguished) and tearing up documents—aroused suspicion. When questioned by a local about their identity, the group failed to convincingly claim they were from Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, prompting them to flee. Meanwhile, one of them surrendered himself to the new authorities and the others are being searched for, he confirms.

Preserving the detention center’s documents was a priority for two of Diab’s colleagues from the association who had been present from the outset. However, they lamented the challenge, saying, “What papers are you talking about? Even if you brought in the American army, they wouldn’t be able to stop the families from accessing the documents. For the first three days, about 40,000 people were there daily.”

Ahmed Yazigi, a member of the White Helmets' board of directors, explains in a phone interview with Syria Untold that, although dealing with detention centers falls outside their responsibilities—tasks he views as the job of the authorities—they responded to families' calls about the possibility of undiscovered cells in Sednaya.

Anticipating questions about the delay in reaching Sednaya prison, Ahmed explains, “There was a traffic jam at the Homs detour that took eight hours to get through. The road was also unsafe, and one of our volunteers was treacherously martyred. Traveling from Idlib to Damascus isn’t as simple as pressing a button—it requires extensive logistical coordination, especially with our teams spread across multiple locations. At that time, we had also recovered 300 bodies in the countryside of Idlib, Aleppo, and Hama.”

Ahmed reflects on that day with a deeply personal perspective: “I spoke with some of my family members. Ten of my relatives were detained in Sednaya. Four of them were released, but six were martyred under torture. The four who were released suffered severe disabilities: one had his foot amputated, another lost an eye after it was gouged out with a screwdriver, and one was left completely paralyzed.”

Expressing frustration about the chaos and partially deliberate attempts to sabotage the surveillance cameras, Diab explains, “The number of families present exceeded tens of thousands, crowding the entire prison and its surroundings. Rumors began to spread, and families started tampering with the detainees’ personal belongings and documents, causing significant damage. While we understand their emotions, the result was enormous harm to evidence that could have uncovered the fate of their children.” However, he emphasizes, “We do not blame them but rather those who opened the prison and allowed such random entry.”

To illustrate the situation further, Diab describes the prison’s structure and the overwhelming crowd: “The door to the detention center is small, like the door to any room, allowing only one person to pass through at a time. Now imagine 30,000 people trying to get in. They had to break down the walls of the entire ground floor to let the crowd enter. If someone had fallen, they would have been crushed without anyone even noticing.” He adds, “There was no force on earth capable of gathering the archives scattered across the ground. My colleagues, who were on-site trying to preserve the documents, screamed for help, but no one heard them. What happened was truly painful.”

Syrian Detainees Play Their Forgotten Music in Berlin

14 December 2024

When asked whether they had considered coordinating with other Syrian human rights organizations before opening the prison, Diab explains that, like everyone else, they were initially in shock over the unfolding events. They believed the operation might halt in Aleppo or perhaps extend to Hama, but when the Operations Department took control of Homs, it became evident that the regime’s collapse was imminent. At that point, they began preparing a team and sought to coordinate with anyone willing to storm Sednaya prison, which ultimately happened, according to his account.

Describing the difficulties of coordination under those circumstances, Diab says their top priority was to get the detainees out before the regime could regroup and potentially seal the prison from the outside. “There was fear that the regime would close the door on them and launch an attack. That fear made the people who broke into the prison forget to bring two keys that could open the entire prison—except for the solitary confinement cells, which had separate keys. We had directed them to where the keys were kept, in the assistants’ shift room.” The situation became even more chaotic with the early arrival of families at the prison. “I never imagined that they would arrive with the first shots,” Diab remarks. “But what happened was that the families, driven by desperation, ignored the celebrations of the regime’s fall and came straight to the prison to find out the fate of their children.”

The families started tampering with the detainees’ personal belongings and documents, causing significant damage. While we understand their emotions, the result was enormous harm to evidence that could have uncovered the fate of their children.” However, he emphasizes, “We do not blame them but rather those who opened the prison and allowed such random entry.

The overwhelming number of people at the prison obstructed efforts to conduct proper inspections. When five of their teams, along with two support teams and an electrician familiar with all the prison’s entrances, exits, and sewage routes (as he had previously installed the cameras), arrived, Yazigi explains, they faced great difficulty. They barely managed to prevent some people from using bulldozers and drilling machines to demolish the prison. “There were attempts—whether deliberate or not—to destroy the evidence and erase the prison’s significance as a symbol, a human slaughterhouse. Thankfully, that stage has now passed.”

Nour al-Khatib, the director of documenting violations at the Syrian Network for Human Rights, told Syria Untold that they had no prior contact with the individuals who liberated the detainees from Sednaya. When their field researcher eventually arrived, the prison was so overcrowded that he couldn’t enter until hours had passed. “The field conditions were overwhelming. The presence of families and media personnel turned the prison into a shrine. Our researcher said he couldn’t have imagined snatching the records from the families’ hands to preserve them. It was understandable that the families wanted to know whether their children had been detained there.”

The Red Cross... Question Marks?!

Many question marks have been raised from the very beginning about the lack of an effective role by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which had remained present in Damascus throughout the years of the revolution, and the visit of its official delegation to the prison on the third day after its liberation.

Speaking with Syria Untold from Damascus, the ICRC spokeswoman, Suhair Al-Zaqout, asserts that they did not neglect their duties, citing the “extremely rapid developments in a situation of overwhelming chaos.” She explains, “The event took place on 8 December, and by 10 December, we were at the detention center. Despite the circumstances, which are well known to everyone, coordinating the visit took us no more than 24 hours.”

Al-Zaqout emphasizes that what was more urgent than reaching Sednaya was delivering trucks loaded with medicines to Al-Mouwasat and Al-Mujtahid hospitals, which received the largest number of Sednaya detainees.

In response to a series of inquiries about whether the ICRC has been present at Saydnaya prison since its reopening and assisted families in searching for missing persons, Al-Zaqout explains, “Our approach is different. Organizing the entry of families, for example, is not our responsibility.” She further clarifies, “We do not have statistics on those released. This is not within our role. Such information is available in official documents.” She adds, “There is no exact number of detainees in Syria. All figures provided by Syrian and international organizations are approximate.”

Al-Zaqout goes on to mention that “35,000 requests for missing persons have been made over the course of the crisis,” noting that the ICRC has been engaged in an “ongoing effort throughout the years of the ‘crisis’. Our work in detention centers is contingent upon the approval of the authorities in the country hosting us.”

She asserts, “We are doing everything we can, but searching for missing persons takes time. We don’t want to raise expectations that with the opening of Saydnaya prison, families will immediately receive information. The authorities will need to verify the information and provide us with answers, which we can then relay to the families.”

When asked about the number of missing persons cases they have been able to resolve during the years of the “crisis,” as she refers to it, Al-Zaqout was unable to provide a specific figure. However, she mentioned that the ICRC has opened two hotlines to respond to inquiries from detainees and their families, receiving 300 requests up until the time of the interview.

What about the United Nations?

Anyone who reaches out to the United Nations or international institutions and mechanisms concerned with missing persons and justice, inquiring about their initial response to assisting the families of detainees after the prisons were opened following the regime’s fall, will hear many claims that contacts were made and coordination occurred with organizations on the ground, but without any teams being deployed or playing an effective role.

The frustration and disappointment felt by the families of detainees regarding the UN's lackluster involvement is perhaps best exemplified by the angry reception given to UN Special Envoy to Syria Geir Pedersen. During his visit to Sednaya prison about a week after its liberation, a young Syrian woman confronted him, asking, “Now you show up?”

In response to emailed questions from Syria Untold about whether they had any presence at Sednaya detention center during the first two days, Robert Pettit, the head of the UN’s International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM), explained that they had no teams on the ground because the Assad government did not recognize their legitimacy and opposed their presence. However, he noted that they had made repeated attempts to reach out, requesting cooperation, but had received no response. Recently, they submitted a new request to the caretaker authorities, seeking cooperation and access to Syria.

If someone had fallen, they would have been crushed without anyone even noticing. There was no force on earth capable of gathering the archives scattered across the ground.

He explained that “the mechanism collects information both in person and remotely, depending on the circumstances, as long as we are able to do so safely and securely, without putting our sources at risk. We collect from areas where we have obtained permission from the authorities to carry out our activities.” This statement raises doubts about whether the mechanism's investigators would have been able to visit Sednaya, even if they were in Damascus, given the security risks on the first day following the regime's fall.

When asked whether other UN bodies and agencies with which they cooperate had investigators or evidence collectors in Syria during those two days or had tried to coordinate with them in Damascus, he explained that the Special Commission of Inquiry on Syria, like the “Mechanism,” did not have access to Syria and had no teams on the ground. He added that they are currently working to reach them as quickly as possible.

He also pointed out that they are coordinating with various UN institutions and committees, such as the “Commission of Inquiry” and the “Independent Institution for Missing Persons in Syria,” which the UN “recently” formed in the summer of 2023. However, he noted that this body, too, does not have teams on the ground.

Despite being formed over a year ago, the independent institution was still without a president. On 19 December, ten days after the regime's fall, UN Secretary-General António Guterres appointed Carla Quintana as the institution's president.

Regarding their response to developments on the ground, Petit listed a group of entities his team was instructed to coordinate and communicate with, including “individuals previously associated with the Syrian regime,” starting from 11 December — three days after the regime's collapse—when the situation was still volatile, as he described it. He also noted that on 9 December, they issued a guide for preserving documentary and digital materials, hoping it would benefit various entities lacking sufficient experience in dealing with such sensitive materials. They are ready to receive and preserve the materials, he emphasized.

The situation became even more chaotic with the early arrival of families at the prison. “I never imagined that they would arrive with the first shots,” Diab remarks. “But what happened was that the families, driven by desperation, ignored the celebrations of the regime’s fall and came straight to the prison to find out the fate of their children.

Petit stressed that despite the partially damaged evidence in Sednaya and other locations, the photos taken remain useful. Even if not in perfect condition, when combined with other collected materials, they will help form a more complete picture of the events. He explained that the loss of documents does not mean the path to justice in Syria is blocked, and that “witness testimony remains crucial in the justice process,” citing recent high-profile cases such as the Koblenz trials in Germany and the Dabbagh case in France.

The International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), based in The Hague, confirmed in an email response to Syria Untold’s questions on 18 December that they had no team on the ground in Syria at the time of the regime’s fall and still do not have one. They are currently in the process of planning their deployment and are coordinating closely with the Sednaya Detainees Association and other institutions on the ground.

The regime has fallen. But a Syrian Kurdish family continues its endless marathon of displacement

23 December 2024

As for whether they are currently helping the families of the disappeared, she stated that finding and investigating them is “the responsibility of the state.” She explained that since 2017, they have been actively working to lay the groundwork for helping the future government address the vast number of missing persons. This includes collecting data from the families of the missing to conduct large-scale identification operations based on genetic testing.

She further explained that they have so far received reports from approximately eighty thousand families, accounting for around thirty thousand missing persons. This data is collected directly from the families of the missing, either through the International Commission on Missing Persons or through a network of Syrian partner organizations.

Who Let Down the Families of the Detainees?

Syrian human rights organizations also bear their share of the blame, as they were seen as failing the Syrian people when the moment of truth arrived. Despite their accumulated experience over fourteen years and the international support they had received, they were criticized for not responding effectively when the opportunity to act came.

Mohammad Al-Abdullah, from the Syrian Center for Justice and Accountability, believes that blaming the organizations is unfair and that they may not be the right party to hold responsible. He points out that the Sednaya Detainees Association was present on the first day, and his center’s team arrived the following day, focusing on collecting documents. He emphasizes, “No one expected the regime to fall in such a manner or this quickly. Talking about preparation? Just two days before the regime fell, the situation wasn’t even on the table. Even if we assume the organizations were in Lebanon and could have arrived within an hour, it wouldn’t have changed the outcome of the investigation.”

He argues that “the situation was chaotic due to the overwhelming number of people, and the spread of fake news by social media players about evidence of detainees being underground, which deeply affected the families of the detainees.”

Al-Abdullah believes that “the process of searching for missing persons is, from our perspective, a long-term process that takes time and relies on evidence and documentation. Therefore, we demand access to documents that can help trace a detainee’s whereabouts, from the place of detention to, for example, a field court or their transfer to another prison. Information about their presence or absence, alive or dead, is crucial. Tracking missing persons through documents is more important than the presence of organizations on the ground when the doors are first opened.”

He attributes the “chaos and randomness” to “the lack of detainee lists. There are lists that no one possesses. This has been our problem with the United Nations in the past, as they would ask us for lists. The lists that organizations have do not necessarily match the ones inside the prisons, which were the responsibility of the Syrian state, and they were not committed to them.”

There were attempts—whether deliberate or not—to destroy the evidence and erase the prison’s significance as a symbol, a human slaughterhouse. Thankfully, that stage has now passed.

Nour Al-Khatib, the director of documenting violations at the Syrian Network for Human Rights, states: “The operation "Deterrance aggression" began on November 27. Aleppo prison was the first to be liberated. At that time, we presented some recommendations, through our field researchers, to the field commanders about managing military operations related to the release of detainees, identifying political detainees from criminal detainees, and preserving the records without tampering with them. However, the field conditions on the ground were evidently beyond the control of the fighters and organizations. This is not an excuse, but rather the reality.”

Al-Khatib believes part of the chaos was deliberate, as any path to justice should involve all victims, not just those under the regime. He is unable to identify where they fell short, explaining that it would have been more effective to form a special committee for prisons, which would distinguish between criminal and political detainees, and involve relief and human rights organizations to help count those who had been released. This would have made it easier for families to search for their loved ones. “Clearing prisons and releasing perpetrators of crimes, including war criminals, is a disaster. We emphasized the need not to break down the doors. Some detainees thought the jailers were coming to execute them. But when there is no cooperation from the other parties, what can we do? The people we sent were civilian field researchers with no authority.”

Pointing out the risks involved, she says that if they had continued working in a professional manner, they would not have sent their field researchers into dangerous areas, as they bear responsibility for the risks they may face. However, she acknowledges the anger of the families and the blame they feel due to the uncertainty surrounding the fate of their loved ones after the detention centers were emptied. She empathizes with them, especially since she herself is searching for three relatives who were forcibly disappeared.

She agrees with Al-Abdullah that the search will take a long time and highlights the significant workload involved: “Every day, we respond to 300 to 400 requests to search through old databases and the documents we receive from various branches. Often, these efforts don’t yield results. There are only a few cases where we have been able to provide an initial outcome to the families. I think we are in a race against time. Everyone is eager to get information, but at the same time, you cannot provide answers arbitrarily. You cannot simply tell a family that their son has died without proper evidence. You need to gather facts to present to the family, which they can then use in any future accountability process. The volume of data we have now is vast, and it will take many months to process. We will cross-reference it with other databases we've gathered.”

The photographs taken of the partially damaged evidence in Sednaya and other locations remain valuable, even if they are not in perfect condition. When combined with other materials gathered, they will provide a more complete and accurate picture of the events.

Speaking about the necessity of not rushing to determine the fate of the forcibly disappeared, "Al-Khatib" commented on the controversial statement made by the director of her organization, Fadel Abdul Ghani, in a television interview, in which he claimed that most of those forcibly disappeared by the regime are dead. She believes his intention was to ease the pain of families who were searching from one prison to another and sleeping in the streets, even those who had been told that their sons were killed years ago. They were affected by a large amount of false information about underground tunnels and basements whose doors had not been opened. She emphasized that Abdul Ghani did not intend to close the case, but rather, on the contrary, to open the door for further investigation into their fate by professionally searching for them in mass graves with the help of specialists.

Mohammad Al-Abdullah, from the Syrian Center for Justice and Accountability, views such an announcement as premature. He emphasizes that the first principle in searching for missing persons is to presume that they are alive until proven otherwise.

Should Justice Be Blind?

26 April 2023

Al-Khatib and Al-Abdullah both acknowledge a persistent weakness in coordination among Syrian human rights organizations, particularly in relation to the collection and sharing of documents. When asked about the situation, they both confirmed that there is no formal coordination between organizations regarding the areas or branches in which they are searching for documents. Al-Khatib, from the Syrian Network for Human Rights, attributes this lack of coordination to the overwhelming scale of the tasks they are facing in the aftermath of the regime's fall. The sheer volume of work, combined with the chaotic conditions, has made it difficult to coordinate effectively.

Al-Abdullah points to the current coordination between their center and the Sednaya Detainees and Missing Persons Association, in terms of working on different detention centers, and that there is a commitment from both parties to collect the documents and compile them together. He also mentions that there is a plan to launch a general call for some kind of coordination regarding these documents and to try to analyze them, because "their size is much greater than the capacity of any single organization, whose goal is to analyze and reach the missing persons."

To whom and when will the documents be returned?

While Syrians were still expressing their joy in the squares over the fall of the Assad regime, and the tears of the families of detainees did not stop, a frantic effort began among "evidence collectors" from Syrian and international human rights organizations, journalists, and anyone related or not to human rights issues, to gather the documents that had accumulated over decades by the Syrian regime in Sednaya prison and other security branches. While some of these human rights organizations aim to preserve them from damage and later use them in prosecuting the perpetrators, the seizure of these documents by other parties was linked to turning them into a "human rights asset," which would inevitably bring them money in the future from donors.

Part of the chaos that occurred was deliberate, because any path to justice would include all victims, not just the regime.

Hiba Al-Zayadin, a researcher at Human Rights Watch who visited Syria after the fall of the regime, told the American program Democracy Now! on December 19 that protecting documents should be a priority for the transitional government. This is not only for justice and accountability purposes, but also because thousands of families are searching for answers about their loved ones, and they have no idea what the government is doing about it.

She believes the interim government should raise awareness about the risks of evidence tampering and the importance of recovering documents with a proper “chain of custody.” If documents are taken without properly documenting “who, how, and from where” they were seized, they will not hold up in court. She emphasized this point to the interim government and called on UN agencies to reach the site as soon as possible. The “Independent Institution for Missing Persons in Syria” guide on preserving evidence includes an “evidence tracking form,” which helps preserve evidence legally, making it usable for later proceedings.

Al-Zayadin notes that while some security measures have been implemented at detention centers, there is currently no coordinated effort to preserve these documents. She stresses that these documents belong to the Syrian people and should remain in their hands. Syrians should be at the forefront of efforts to protect them, with support from the United Nations and other international actors.

Diab Seria, Director of the Association of Detainees and Missing Persons of Sednaya, expresses frustration over the lack of cooperation from some Syrian human rights organizations regarding the sharing of documents. He believes that many organizations, activists, and foreign journalists have taken large quantities of documents that no one has the right to keep, with the intent to profit from them later. These groups often present themselves as analysts of the data or publish books claiming to expose "leaks from Syrian intelligence."

He notes that the Sednaya prison archive is so vast that collecting it under the current circumstances is extremely difficult. The archive contains everything that has happened in Sednaya prison since 1987, including not only crucial data but also routine, insignificant orders. It’s not as simple as finding the names of detainees and important information right away. Diab estimates that it will take about a year to sort through the documents and identify the missing information. Without cooperation from human rights organizations, they will face significant challenges. Diab suggests pressuring funders to stop supporting projects related to these documents in order to compel those holding them to return them, as they are, after all, "the history of a country."

When the Red Cross was asked about the amount of documents they had announced collecting from Sednaya prison, the committee’s spokeswoman, Suhair al-Zaqout, said in an official statement, "We collected as much as we could and made sure they were placed in closed rooms before leaving the site," considering that "preserving them is the responsibility of the authority controlling the ground. The committee does not keep the detainees’ documents." When asked about the party to whom they had handed the documents, she said, "It is very difficult to determine. There are many parties working on the ground." Diab stated that the situation in the prison was chaotic, and as a result, anyone carrying a weapon was considered an "official" there.

After days of chaos, document collectors on the ground noticed that the military operations management began to place guards on the documents and started requesting temporary permits for photography only from the Damascus Police Leadership, as clarified by the Syrian Network for Human Rights and the Syrian Center for Justice and Accountability to Syria Untold.

The involvement of human rights organizations, journalists, and even social media content creators in accessing parts of more than fifty years of dictatorship heritage opened a discussion on the conditions that will bring it back to the future Syrian state.

War crimes investigator William H. Wiley, from the CIJA organization, and his team of document collectors on Syrian soil collected nearly 1.3 million documents before the fall of the regime, smuggled them out of Syria, and stored them somewhere in Europe. Wylie compares the current situation in Syria in an interview with the Sunday Times to Germany in 1945, Iraq in 2003, and perhaps Central and Eastern Europe in the early 1990s, where the document collectors working with him in Syria are racing against time to gather as much as they can. As areas fell under opposition control, they hired ten additional document collectors in Syria to join the 43 employees who were already working there. However, they estimate that what they have collected so far is just a drop in the ocean, with one hundred million pages that will require a massive infrastructure for something larger than Nuremberg.

In this context, Nerma Jelacic, the Director of Administration and External Relations at CIJA, explained to Syria Untold that they typically work with law enforcement authorities rather than directly with victims. They currently collect and store documents inside Syria, noting that they cannot work in areas controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, such as Saydnaya prison, because it is classified as a terrorist group. Instead, they operate in areas controlled by other armed groups.

From our perspective, the search for missing persons is a lengthy process that takes time and relies on evidence and documents.

Regarding whether they will hand over all the documents, including those taken out of Syria since 2011, she said this depends on the Syrians electing a government. The current government is a caretaker administration and does not include a body responsible for securing these documents. Therefore, it is too early to determine to whom and when they will be handed over.

From her personal experience in Bosnia, she recalls that the war took place in the nineties, and some mothers are still burying fragments of their children's bones because they cannot find the rest of the remains. She explains that revealing the fate of the missing is "frustrating and requires the efforts of more than just one organization, institution, or even the United Nations alone. It requires the collaboration of all these groups and actors, and consideration of how to implement this as quickly as possible. SIGA cannot do everything, and no one can. What we can do is preserve the documents so they are not lost, and then Syrians will decide the mechanisms for transitional justice and the methods for finding the missing. This is not our decision."

The Syrian Network for Human Rights also confirms, according to Nour Al-Khatib, that "the documents are not the property of the network. Until the situation becomes clearer, they will be handed over to the new government or the institution that will take on the task of searching for the missing."

As for Mohammed Al-Abdullah from the Syrian Center for Justice and Accountability, he believes that “the documents are in our custody for the Syrian people, and we will hand them over to any elected government later to take on this role. We have two teams of ten people in Damascus working on documentation, and they tell us that these documents are beyond the capacity of any party to photograph and transport. There is an archive of fifty years of paperwork, with buildings full of papers, and no one can take them out or protect them.” He explains, “If a transitional phase is established, supervised by an institution, group, Ministry of Justice, or any party with credibility and technical standards, that can benefit from the papers, we will immediately share them. Currently, our role is limited to preserving and archiving these documents, and beginning to analyze them. We hope that a national committee will be formed to search for the missing, under the management of the Ministry of Justice. If that is not available, we will begin to analyze them.”

Prison: Writing versus experience

27 February 2020

Al-Abdullah warns against publishing such documents online, recalling how this previously led to widespread liquidations in Iraq, as they contained information about informants and snitches. For this reason, his center usually does not publish them “in order to protect the victims, avoid causing violence, and prevent alerting the accused, who might be tried if they reach a European country, for example.”

Diab Seria from the Sednaya Detainees Association seems skeptical about the possibility of individuals and small institutions returning these documents, regardless of how promising their claims may sound.

Listening to these sources, one can conclude that a combination of factors and circumstances made what was revealed before our eyes on the screens inevitable. The most notable of these include: the prevention of UN investigators from being present in Syria under Assad’s rule, and the slowness of their movement since the fall of the regime; the "professional" behavior of the International Committee of the Red Cross; the liberation of Sednaya prison by a small group of former local fighters, who were caught off guard by the possibility of a surprise attack by the regime; the almost non-existent coordination between Syrian human rights organizations, whose capabilities were overwhelmed by the demands of following up on the rapid collapse of the regime; and most importantly, the prison quickly becoming a pilgrimage site for tens of thousands of families of detainees, but also for eavesdroppers, thieves, and social media exploiters, who have fed—and continue to feed—on the blood and suffering of Syrians.

In light of this comprehensive national tragedy that Syrians are experiencing, calls are being made by human rights and international organizations to protect the mass graves, which may hold partial answers that families could not find in detention centers, and which may not be available in the vast amount of documents accumulated by organizations or piled up in security branches, or still scattered on the ground. This is happening amidst a clear lack of coordinated efforts by the current caretaker government to secure and preserve them. On December 22, Ahmad al-Sharaa, the leader of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, spoke about "the existence of many specialized committees, which are based on forensic evidence investigations, with the help of some international expertise, to look into the case of the missing." It is unclear which committees al-Sharaa is referring to or when they were formed.

“ICMP has collected over 700 reference DNA samples from families of missing persons. The results of these tests will assist in identification efforts once systematic recovery operations begin in Syria. We have also received anonymous data regarding the locations of approximately 70 mass and clandestine grave sites,” ICMP told Syria Untold.