“Every day I walk between the houses, carrying a bucket and a mop, as if I were wiping away the traces of war and fear from the people". While the war may be over, the fear hasn't ended for 62-year-old domestic worker Hind. "Before the liberation [Assad regime’s fall], I knew all the neighbors and was entrusted with people's homes. I used to go in and out and no one would suspect me. But today the world has changed, and I walk like a guest on every street. All I have left is my mop and my bucket; they are what make me wake up in the morning and go. Maybe today I will find a home that will accept me, maybe not”.

Hind has been working as a cleaner since around 2009, after her husband divorced her some fifteen years ago: "I never worked outside the home during my marriage,” she said on a Whatsapp video call with Untold last August. In the city of Tartous where she resides it is still difficult to move around from one neighborhood to another. The women’s fear is kidnappings and random killings that take place in different areas of the Syrian coast and leave their impact on people, out of fear, shrinking, and immobile, except for extreme necessity. Also cleaning houses, at the time when she started, became necessary “because no one else could pay the bills, and the state did not provide us with any assistance."

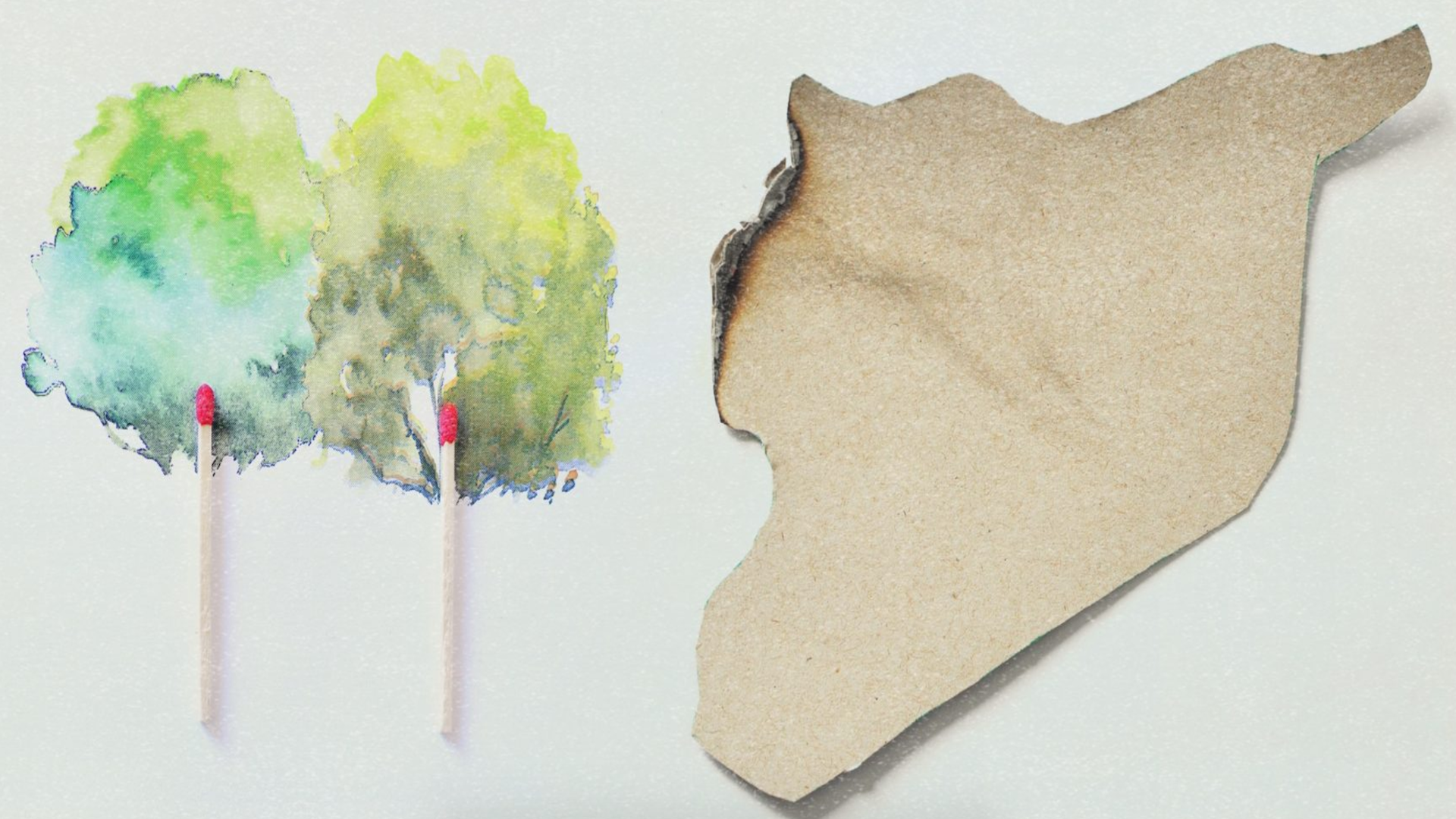

It was even more difficult after the Syrian revolution in 2011, soon turned into a war that led to a significant increase in poverty. A UNDP report last February stated that ‘more than 20 million Syrians, or 90% of the population, are financially poor.’ The year before, in May 2024, the World Bank stated that ‘poverty affected 69% of the population in 2022, with extreme poverty reaching 27%’. Although the figures differ between reports, poverty is a reality that has pushed many women into work. ‘Since the war, Syrian women gained autonomy’, it's the title of a reportage in Le Monde last September. ‘In many cases, they have become the breadwinners of their families, but society is still dominated by men.’ Their stories and their pain have been obscured, as was the case with Hind.

From the Al-Insha’at neighborhood…

In the old al-Insha’at neighbourhood, Hind was trusted and reliable among her neighbours, having lived there since around 1998. "Before 2011, I worked regularly, day in and day out, and people respected me”, she said to Untold. “This continued until the fall of the regime when security collapsed, people became afraid, and invisible lines were drawn between neighbours”. Wearing a dark cloak, with a cheap gray coat over it, her veil is parted, covering her thin silver hair, and her face pockmarked with many wrinkles. “I had been living in this neighbourhood for many years; it was mixed, and it’s now divided: sectarian terms are shouted loudly. Every time someone asks, “Where are you from?”, it kills the peace”.

Every time someone asks, “Where are you from?”, it kills the peace.

Hayy al-Insha'at is one of the relatively old neighborhoods in Tartus. Home to families who have migrated from the countryside of the province alongside urban families, before 2011 daily relations were based on long-standing neighbourliness and mutual trust. After the war, the economic factor became the greatest concern for people due to declining living standards. But after the fall of the regime, the maps of trust changed significantly. An elderly neighbour with a distinct coastal accent and elongated vowels, who spoke to Untold on the phone, said: “We used to consider her (Hind) part of the family, but after the events (the fall of the regime), our hearts ache and our tongues are tied, not because of her mistake, but because fear has turned us against each other”.

Hind has a soft Tartus accent and her voice lowers when she mentions checkpoints and her neighbors. "Before the fall of the regime, I used to clean the house of two neighbours in their sixties. After a while, one of them became hesitant and refused to have me in the house when they had guests. They told me, ‘We're not comfortable right now, the situation has changed’. And indeed, fewer people called me. When hatred entered the name of sectarianism, I started hearing phrases like, ‘We can't accept anyone outside our sect’. And I felt like I had been torn from my life".

Hind is from the Alawite sect, but most of her work in recent years has been in homes where approximately 80% of the residents are Sunni. This has just recently changed, as many human rights organisations and independent sources have documented. The 2025 March massacres which targeted Alawite civilians has led to waves of social and sectarian segregation in mixed areas, forcing many to change their place of residence or movement patterns due to fear, threats or neighbourhood gossip.

My short odyssey in the (new) Syrian security branches

26 August 2025

During this time, Hind received help from some of the households where she currently works, from clothes for her grandchildren to leftover food or extra money to continue travelling between the city's neighbourhoods every morning. When she talks about her grandchildren, her pitch rises suddenly. "A lady gives me a symbolic amount, saying, 'Take 5,000 pounds! It's a small amount, but it's the price of a loaf of bread today. My neighbours give me clothes for my grandchildren, and that makes me happy, as if it were a holiday. My grandchildren are what keep me going. When I dress them in new clothes, they are happy, as if it was a holiday".

Today, Hind lives with her divorced daughter and her divorced son, whose ex wife went to Damascus in search of work. They had two daughters, aged 13 and 9, and a six-year-old son. Hind’s son has a disability in his right leg and cannot do heavy work or even move around comfortably, so Hind is the primary breadwinner for the family, along with her divorced daughter, who gives private lessons to children in the Ras al-Shaghri neighbourhood where they currently live.

“When I got divorced, I felt like I had lost not only my social support, but also the small safety net of neighbours and family. Even standing in the kitchen became difficult... When I started working in people's homes, my children hated visiting me at night because I was exhausted and couldn't cook them a meal”.

Hind tried to remain steadfast in the neighbourhood, moving from house to house, as if she was cleaning wounds that no one could see. One of those wounds was the loss of trust. "People who trusted me before the war became suspicious, and doors were closed in my face. I said, 'Maybe it's fear! But fear became a justification for discrimination".

People who trusted me before the war became suspicious, and doors were closed in my face. I said, 'Maybe it's fear! But fear became a justification for discrimination.

She began to feel like a stranger in her neighbourhood. "People no longer let me visit their homes, using excuses such as circumstances or that they no longer need me, but I heard from my neighbours that the reason is that I am not from their sect and because my ex-husband (who is deceased) was in the Syrian Arab Army years ago with the rank of colonel, and now that has become a charge against me. It's as if I've become a stranger and a threat."

Where she used to walk and to laugh with the women of the neighbourhood, she is now met with cold stares: "At first, they would call out to me: “Come and have some coffee”; but now their looks say: 'Why are you still here?”

Hind's words are confirmed by one of her neighbours (who declined to give her name). She spoke to Untold on a short phone call, her voice sharp: “This is unfair. Women work hard their whole lives to maintain their honour, and what happened to her has nothing to do with her integrity. The atmosphere that has been imposed on us has silenced even the good people.’ Another neighbour (who declined to give her name) said: ‘Hind was well known, but people became afraid. Sectarianism played a big role. Even if she was a clean and good person, her presence became embarrassing for some families, as if she were a stain. This hurt us because we lost a loving neighbour, and we saw how sectarianism kills relationships that have been built over years.”

Hind remembers one of the houses: “I was responsible for everything from laundry to cooking, but suddenly the lady of the house said to me: ‘May God bless you, Hind, but there is no more work for you!’ After a while, I heard that they had hired someone else to replace me.”

This discrimination was not just a matter of work for Hind, but also a matter of dignity; she lost her monthly income as well as her sense of self-confidence: “The pain is that they kick you out of their lives as if you were a danger, after all these years of me being entrusted with the secrets of their homes.”

And this did not happen to Hind alone. Nada, a 55-year-old house cleaner in the city of Latakia, spoke to Untold using a pseudonym: "I worked for a large family for 12 years. I had a key to the house, just like their children. But with the recent events, they started hinting that things had changed, and finally they told me outright: ' You don't look like us, and people are starting to talk about us because we have you here’. I started dressing more modestly, not because I'm religious, but because I don't want to be asked at the checkpoints where I've been and where I'm going. So I toned down my speech, became more modest, and started walking without attracting attention".

I started dressing more modestly, not because I'm religious, but because I don't want to be asked at the checkpoints where I've been and where I'm going. So I toned down my speech, became more modest, and started walking without attracting attention.

Nada describes how she felt let down after many years of service: “They left me with my ID and official papers. Did it never occur to them that I might hurt or steal something? But this war has changed us and taught people to fear each other more than they fear theft. Suddenly, sectarianism took precedence over trust”.

…to the al-Shaghri neighbourhood

This touched Hind's heart, leading her to decide to leave for the Shagri neighbourhood because "I felt like a guest, not a neighbour, even though I lived among them. I experienced a very difficult isolation, and I left the neighbourhood with my heart torn in two: one half with the houses I considered my family, and the other half screaming, 'Why did this happen? "

She adds: "I remember a house I cleaned for years. The man who owned it always said, ‘Welcome, Umm Majid, come in, please’. After the revolution, his son, who had been living abroad for years, returned and started interfering in the house. I heard him talking loudly on purpose. He said to his father, 'I intend to settle in this country, so we will not allow strangers into our house’. He said it without consideration for my feelings, and I remained silent, because silence guarantees bread for today".

After the March massacres, the fear for her family increased. "I went to the Ras al-Shagri area seeking safety. I thought that if I changed neighbourhoods, the embarrassment would end. But even Ras al-Shagri was not a blank slate; break-ins, confiscations, and destruction of homes became a reality after the takeover by armed factions. Sometimes I would come to clean a house and find the door broken or the windows smashed, or the owners would tell me, “Be careful, they were on alert all night and checking the checkpoints”.

Scenes from the disasters. Qardaha and its countryside

27 July 2023

Ras al-Shagri is a coastal area south of Tartus known for its blend of rural and urban spaces, and many of its families are closely related, giving it a cohesive local protection network. After 2011, it witnessed waves of displaced people coming and going, and low-level tension that rises when military control changes. One of its residents says: "Are they here among us? Yes, they are, and it's a shame they work silently day and night. Some people treat her well; her presence is a blessing and we cannot deny her hard work."

Hind testifies: ‘No one has insulted me openly here, but there have been hints. Once, someone said, ‘May God help you’, so I became more careful, working and keeping quiet”.

“I am no longer myself…”

What happened to Hind also affected her mental state, her body and her movements. "Early in the morning, I stop the minibus, and every passenger looks at me; my work is obvious from the mop. At the checkpoints, they ask me: Where are you going? Where is your ID? Sometimes they ask so many questions that my heart sinks. I don't know how to talk about politics, but I know how to walk with dignity." It is the same fear that has left its mark on everyone.

One of her old neighbours from the al-Insha’at neighbourhood says: “Hind was always clean and kind, but the feeling of war made us afraid, and it wasn't easy to see her leave her home, but life became difficult and painful. Some houses are filled with children's laughter, while others are filled with the cries of mothers who have lost loved ones. Each house responds to me in its own way; one house sees me as a second mother, another sees me as a stranger, and a third slams the door in my face”.

Human Rights Watch mentions in their report last December cases of harassment and abuse of women and girls at checkpoints, including testimonies of ‘verbal abuse and harassment at checkpoints.’

A minibus driver at the old bus station spoke to Untold: “Women are afraid to talk at the checkpoint. They ask them questions and see them holding their identity cards with trembling hands”.

This behaviour is not unique; human rights reports indicate that violence and threats have forced women to act more cautiously and give up some basic freedoms in order to protect their personal safety. Human Rights Watch reports that women ‘faced discriminatory restrictions on their clothing and movement’ during the conflict.

Some houses are filled with children's laughter, while others are filled with the cries of mothers who have lost loved ones. Each house responds to me in its own way; one house sees me as a second mother, another sees me as a stranger, and a third slams the door in my face.

Hind now works for a woman named Fatima. She told us in a brief WhatsApp call: "I've known Hind for a long time, but when she arrived in Ras al-Shaghri, people started giving her work. I see her as trustworthy. She keeps the house clean and tidy and doesn't ask for anything extra. Sometimes I give her leftovers from meals, sometimes clothes for her children, because I know she has limited means. Good people help as much as they can."

Hind still spends her days between the fear that surrounds everyone and the work she can find, which she describes in detail: "I open the box with my tools: a mop, a bucket, an old brush, and a cloth. I perform my usual work ritual as if it were a prayer ritual. I enter the house with determination; I start with the dust, clean the corners, tidy the table, wipe the footprints. Each house responds to me in its own way; one house sees me as a second mother, another sees me as a stranger, and a third slams the door in my face."

When asked about her dreams, she tells Untold: "My greatest dream is to live in safety every day and to be able to provide enough food for my grandchildren. I dream that people will see me as a human being, not as a sectarian symbol or a divorcee. I don't want pity, I want a simple job and simple protection. Working women must be treated as human beings who deserve security."

“If people cleaned their hearts the way they clean their homes... maybe we could love each other again”, she concludes.