“Radio Fresh: A Syrian History” is part of the “Meglio di un romanzo” series, curated by journalist and co-director of Q Code Magazine Christian Elia for the Festivaletteratura in Mantua. Originally published by Festivaletteratura and Q Code Magazine, this revised and translated version now appears on SyriaUntold.

The first chapter, “A Story that Begins in Idlib”, is available here.

The second chapter, “Citizen journalists despite all”, is available here.

The third chapter, “Between radicalization and foreign intervention”, is available here.

It was an email that arrived one morning, unexpected. The US State Department announced that President Donald Trump had decided to freeze $200 million in aid for humanitarian groups in Syria. Among them was Radio Fresh.

There had been a bombing in Manbij, northern Syria. Two members of the US-led coalition—an American and a British—were killed. Five others were injured. According to a senior US military official, the attack was the work of remnants of the Islamic State.

The new administration was quick to respond, but it didn’t address the alleged attackers. It targeted others. Raed Fares read that email on 17 May 2018, when he entered the radio station’s office, sat down, and opened his inbox as usual:

“(We inform you) with great regret that the United States has decided to discontinue funding for projects including Radio Fresh – effective June 30”.

The news spread quickly.

Many media outlets protested—not only because their funding had been cut, but especially because it had also been withdrawn from the White Helmets. After the pressure, the United States restored funding for the Syria Civil Defence, but journalistic groups and civil society were left without support.

“Trump’s goal is to immediately end US involvement in Syria. But I have bad news for him: without funding and support for independent voices like Radio Fresh, the world may witness the rise of another Islamic State in Syria, and that would create a long-term security threat for the United States. […] Americans will have to spend billions more to protect their allies—and even themselves—from new threats”, the director explained.

And it was at this point that the debate began, as described by journalist Harun al-Aswad. He reported the differing positions on the issue, ranging from those who defended the idea that it was possible to maintain an independent editorial line without bending to the interests of donor countries, especially if and when the number of followers increased and “you become stronger and can therefore control who finances”, to those who, on the other hand, believed that this dependence made truly independent reporting impossible, to the point of stating: “There is no independent work in Syria”.

Regardless of the sides in the debate, one thing was certain: Western support was insufficient. Furthermore, several media executives denounced the progressive decline in aid precisely in the years when it was most needed. With the beginning of Russia’s direct intervention, the balance was rapidly shifting in favor of the regime. In 2016’s autumn Aleppo fell. Groups like al-Nusra Front became more powerful among opposition forces.

Radio Fresh: A Syrian history

11 August 2025

That the balance of power was shifting was clear to everyone already by the end of 2015. A sense of unease and instability was growing. Zaina Erhaim also perceived it in the director of Radio Fresh during a journalism training course for women, held in 2015.

“Raed looked more scared than I’d ever seen him. He had an alarm installed in his car. […] He moved around his own town like a ghost and rarely returned home”.

Al-Nusra began targeting Radio Fresh in 2013, even before ISIS. With its raids, the group once blocked the broadcast of the program “Syrian Dialogue”. It then requested that the radio station's activity be monitored from its own offices. Raed Fares refused: “You have to monitor the broadcasts, not what the people inside the radio do!”. Al-Nusra responded by banning music, which it considered unlawful, and threatened to block the broadcasts again if the radio station did not comply with its directives. Moreover, in December 2013, the director was kidnapped and beaten by the group, which nevertheless released him shortly afterward, having no official charges to justify his detention. Between 2014 and 2015, the director was kidnapped four more times. He was even tortured once, but was always released.

A challenge to censorship efforts

Between 2015 and 2016, most of the Idlib governorate remained under the control of either al-Nusra Front or the Free Syrian Army (FSA). However, in 2016, a new actor emerged: Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which originated from al-Nusra and included other Islamist factions. That year, journalist Harun al-Aswad was traveling to Kafr Nabl. Working in Aleppo, he moved back to his hometown, Damascus, at the beginning of the revolution to document events alongside his colleagues. He had recently been released on judicial bail after spending a year in prison, following his arrest by a branch of the security forces known as the Palestinian Branch, also referred to as Branch 235. Shortly after his release, he lost all his equipment in an airstrike on Damascus. Facing the possibility of being summoned back to court, he decided to board one of the green buses headed to Kafr Nabl. These buses transported civilians and fighters from besieged cities—those unwilling to submit to the regime—toward opposition-controlled areas, particularly the Idlib governorate. Upon arriving in Kafr Nabl, with only a Samsung S3 phone in his pocket, he heard about Radio Fresh—and with that phone, he began working for them.

I had an interview with Harun al-Aswad last April and during our videocall he explained how “moving to Idlib made everything easier. There were only a few of us, five or seven at most, working as correspondents for various media outlets”, he said.

He met Raed Fares and Hammoud Jounin one day while filming the arrival of displaced people from Homs. Simple people, he added—meant in the best possible way.

“They were kind. They organized, they worked, they built: they were always on the move. Smiling. And open to talking to anyone they met on the street.”

Raed Fares: Turning Emotional Pain into Awareness

28 November 2018

One day, however, he decided to speak with them because the salary was low. Around one hundred dollars—it wasn’t enough to pay rent and live in a new city.

Raed Fares replied that he understood and that Harun was right to bring it up. However, the goal of Radio Fresh was to help as many people as possible by offering employment and training—especially to those in need. For that reason, it was better to hire more people with modest salaries than just a few with full pay. Harun accepted the explanation: “That was their strategy. And it worked!”. By 2018, Radio Fresh had more than 64 employees. “There were incredible people at the radio station, many of whom still work as correspondents today”. Harun worked at the radio for five months before moving to Turkey, and later to Paris, where he now studies journalism at university.

During those months, working in Idlib was difficult. Every day brought news of airstrikes. “The day I arrived, I remember 12 or 13 ballistic missiles hit the city”, said Harun. “Moving around was dangerous. There were clashes between al-Nusra, HTS, FSA. Sometimes even ISIS. In fact, no one lived in Idlib anymore”.

This last point is confirmed by Zaina Erhaim: “Our car was the only civilian vehicle heading toward the city of Idlib, while everyone else was fleeing, carrying hundreds of frightened families.” She, too, was experiencing the changes in the governorate firsthand. She recounts wearing a veil and a long coat in order to keep working.

Her colleagues in the area also noticed the changes, including those at Radio Fresh. Al-Nusra had long been trying to dismantle the radio station’s gender equality project. It ordered the dismissal of all female journalists and their replacement with male counterparts.

Radio Fresh didn’t hesitate to respond. It circumvented the order by digitally altering the female journalists’ voices. When listening, they sounded like men. Hybber Abud, a Radio Fresh journalist, said:

“I burst out laughing! I couldn’t believe that after all my effort and training, my news reports would come out sounding like that! I categorically refused to do it. But then […] I saw the funny side” (from 5:30 to 6:40).

Radio Fresh wasn’t just a media project, but a challenge to censorship efforts. Every broadcast, whether altered or not, represented an act of resistance. They arrested the director again, this time along with a colleague.

The turbulent 2016

Despite the editorial team’s creativity, the radio station continued to suffer attacks. On 1 January 2016, Raed Fares was arrested again and released almost immediately, only to be detained once more just ten days later. That day, 10 January, heavily armed members of al Nusra stormed the radio offices. They confiscated computers, cameras, various equipment, and arrested the director again—this time along with a colleague: photojournalist Hadi al-Abdullah.

Originally from Homs, Hadi began documenting events as a journalist at the outbreak of the revolution, reporting from his hometown, as well as Aleppo, Qusayr, and Idlib. Al Nusra considered their actions necessary and justified, citing repeated, ignored requests not to broadcast songs they deemed “promoting debauchery,” which they also considered blasphemous and strictly forbidden. Raed was also accused of violating Sharia law due to a Facebook post that al-Nusra found unacceptable.

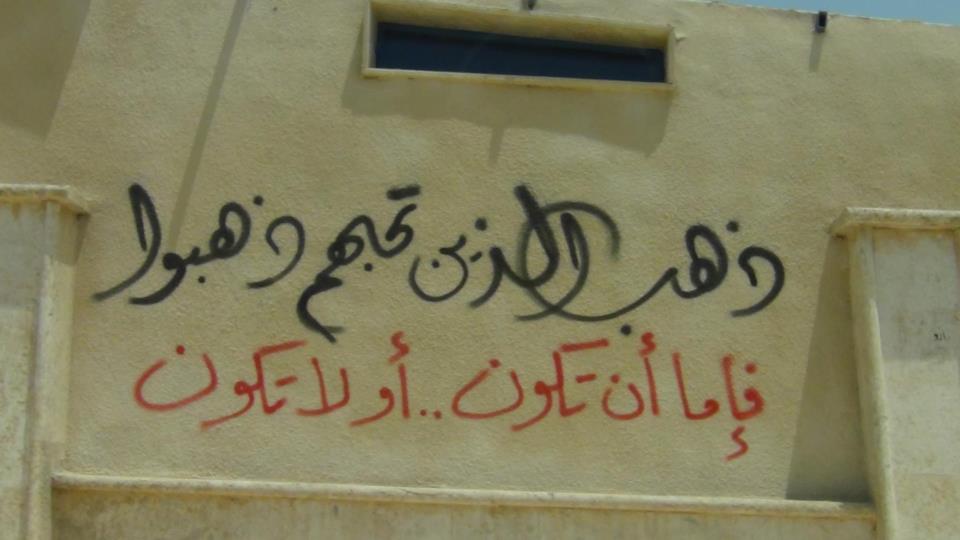

Twenty-four hours later, al Nusra declared that it had released both journalists on one condition. Hadi al-Abdallah had to guarantee Raed Fares’s actions, even if he was summoned by the Sharia court.. He also had to endorse al-Nusra’s judgment that the director’s post did indeed constitute a clear violation of Sharia. At that time, al Nusra also declared that among the reasons for the recent incursion were graffiti on the city’s walls, considered offensive to Islam.

As soon as he was released, Raed Fares decided to write a new Facebook post: Ideas are freedom. Later, this became the Radio's motto.

This post also reflected what had happened during those 48 hours: the population had tried in every way to pressure al-Nusra to release Raed Fares and Hadi al-Abdullah and apologize. And civil society succeeded. Indeed, an apology arrived, acknowledging the abuses committed as a mistake and assuring that all equipment confiscated from the station would be returned or compensated in the event of damage. It was al-Nusra leader himself, Abdullah al-Mhaisni, who wrote in a resounding tweet:

“Saddened when I read from the words of our beloved media personality Hadi Al-Abdullah, vis-a-vis the behavior of al-Nusra Front brothers. This is particularly so, given that there was no need for a raid—a summons would have sufficed”.

For Raed Fares, this was a moment of immense pride, because it confirmed his thinking, and more generally the thinking of the radio itself: a strong society is the best bulwark against tyranny and terrorism. He said:

“The liberated areas in which we operate are particularly vulnerable to power struggles, and supporting civil society and media groups here is absolutely crucial. Recent history has repeatedly shown us that lasting peace depends on the existence of a vibrant civil society and free political discourse—a marketplace of ideas where new voices can challenge dictatorship and terrorism. We have also witnessed cases—in Afghanistan and Iraq (where Daesh and al-Qaeda emerged)—in which the lack of civil society building undermines democracy”.

“Today [1 January 2016, author’s note], civil society triumphed over weapons”. The attack had hit the radio station hard, and for 20 days it was unable to broadcast. When Radio Fresh returned to the airwaves, the music was gone. In its place: strange new sounds. Whistles, ticking noises, piercing explosions! Stadium cheers, applause! Bird chirps and bleating goats…

The director explained:“They tried to force us to stop playing music on air, so we started to play animals in the background as a kind of sarcastic gesture against them”.

What began as a provocation quickly transformed into a symbol of resistance. Each broadcast became a creative way to circumvent censorship, demonstrating that freedom of expression always finds a new way to survive.

The attacks continued: “I received a WhatsApp message at 12:30 at night from Raslan’s brother, telling me that he had been kidnapped by masked men while returning home to the town of Khan Sheikhoun”.

These are the words of Ayham Asteef, a member of the editorial staff of Radio Fresh. His colleague and poet Ahmed Raslan was kidnapped on March 23, 2016. The radio station’s management contacted several groups to try to determine who was responsible for finding Raslan and identifying the kidnappers. The only clue they had was the vehicle used in the kidnapping: a red Range Rover.

In May 2016, another blow. Jund Al Aqsa, another Salafist Jihadist organization, seized the equipment, accusing the editorial staff of spreading false information. The militia allowed the radio station to resume broadcasting on 13 June 2016.

That month, Khaled al-Issa and Hadi were working in the rebel-held area of Aleppo. Injured by a barrel bomb explosion, they nevertheless continued working. Al Jazeera reported the episode:

“Khaled al-Issa and Hadi al-Abdullah are crazy and sane […] Thank God for the safety of your dragons,” commented Raed Fares from Kafr Nabl.

Khaled al-Issa shot his first video on 1 April 2011. He was 19 years old. On 7 February 2011, Bashar al-Assad granted citizens access to social media. Khaled al-Issa, however, did not yet have a Facebook or YouTube profile where he could have shared his first footage. That wasn’t his initial intention. He simply wanted to preserve a memory of that revolutionary moment to show friends and family. He didn’t film as a journalist. He said he became one “by accident”. The bias in journalism in favor of the regime and the ban on international journalists drove him to want to document the events. In 2012, Khaled managed to get his first camera and from then on he devoted himself tirelessly to covering everything that happened in Kafr Nabl. So much so that Raed Fares had to force him, at times, to take days off. His dedication did not go unnoticed. Christina Abraham writes:

“Go look at any photograph of Kafr Nabl’s now-famous revolutionary banners and cartoons, and Khaled will probably be there, holding the banner. And if he’s not in the photo, he most likely made the banner or took the photograph”.

And it’s true. As long as social media profiles remain accessible, Khaled al Issa can be seen everywhere. His dedication led him to work side by side with Hadi al-Abdullah. “We thought day and night about the need to provide evidence,” they said. For Khaled, that meant staying—even when he had the chance to leave. As reported by 100 Faces of the Syrian Revolution, he refused several times to leave Syria.

On 16 June, an improvised explosive device (IED) was planted outside Khaled al-Issa’s apartment. The explosion once again injured both him and Hadi. Pulled from the rubble of his home, Khaled was transferred by civil defense teams to Turkey for medical treatment. While Hadi al-Abdullah’s injuries were treatable, Khaled al-Issa’s were so severe that his only chance of survival was to reach Germany for surgery.

From that 16 June, Raed Fares wrote a Facebook post for his colleague every day.

But the days passed, and the visa from the German Foreign Ministry arrived only on 24 June, when it was already too late. Khaled was only 24 years old.

Whoever was behind the assassination remains unknown, a faceless shadow added to the many others of the war. Christina Abraham also wrote:

“His death will likely go unnoticed by most. Now he is one among many. Another young Syrian, missing in action. Another voice of hope, drowned out. Now he joins his 470,000 sisters and brothers who lost their lives because one family refused to relinquish power in Syria. And because world powers were content to watch them die, just so they could move the pieces on a chessboard […]. And because the rest of us looked away while it all happened. […] I am proud to say that Khaled al-Issa was a dear friend”.

From 2016 to 2018 (and even after 30 June 2018 when USA funding would have been cut) the radio station continued to carry out its work despite adverse circumstances, dealing with all the actors involved in the conflict. That summer, however, Zaina Erhaim had contacted Raed Fares. She was worried. She asked him to be careful, because the number of assaults and attacks against him had increased. He told her:

“God only takes good people. I’m an ‘arsa. Don't worry”.

The same old story

Khaled al-Issa’s death is part of a broader pattern of violence against journalists and media workers in Syria.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), 143 journalists and media workers were killed between 2011 and 2018.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) recorded 263 killed for the same period. It also recorded 30 forcibly missing or disappeared, of whom 8 are still missing. 101 were taken hostage, of whom 34 remain hostages. 50 were arrested, of whom 19 remain in custody today.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) counts 691 journalists and media workers killed between 2011 and 2018.

Do these numbers ring a bell?

According to the CPJ, between 2023 and 2025, 176 Palestinian journalists and media workers were killed, including Fatma Hassona, 25, killed in an Israeli airstrike on 16 April. Only the day before, she had received news that Sepideh Farsi’s documentary Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, in which she starred, would be presented at Cannes in May.

Clearly, times are different, as are circumstances. However, these years reminded me of a 2023 interview by Democracy Now to Yassin Al-Saleh, author of The Impossible Revolution: Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy, where he said:

Syria is a microcosm because what is happening in the country is linked to global international structures. […] The Middle East is the most internationalized region in the world. […] So, we have all these state and non-state actors with important interests in the country at the same time, you see that almost 30% of the population is moving to countries near and far. So, it’s globalized. So, in our own way, we can say that the world is a macro Syria. And I believe that the Russian invasion of Ukraine would not have been possible without accepting and tolerating Russian intervention in Syria. No one condemned it, neither the United States, nor the European Union, nor the UN condemned Russian intervention in Syria. I think this was a very dangerous message”.

Syria has been a testing ground for international law, to see whether it applies to everyone or to no one. This should raise questions, as we saw in the second chapter with the chemical weapons episode, which in turn paved the way for Russia’s intervention in Syria in 2015. We see it with journalists and media workers who suffered the consequences of constant violations of UN resolutions, including 1738 (2006) and 2222 (2015) on the protection of journalists, media professionals and associated personnel in armed conflict.

What have we learned from this? What questions have we asked ourselves, individually and collectively, in light of these precedents? What responsibilities do we have?