The author is a computer scientist, one of several prominent technical analysts who covered internet outages during the 2011 Arab Spring and its aftermath. In his work for Renesys and later Dyn Research, he connected with “Mahmoud,” a senior Syria Telecom engineer who, at great personal risk, became a trusted source and shared internal details that informed the analysis. “Mahmoud” is a pseudonym; he has lived safely outside Syria for several years.

This is Mahmoud’s story.

It was the middle of the summer of 2013 and Mahmoud was making a trek across northern Syria. The 33 year old lived in Aleppo where he worked for Syria Telecom as a network engineer. But on this day, the last day of Ramadan, he was packed into a crowded bus heading southwest to Idlib to celebrate Eid al-Fitr with family and friends.

Thirty minutes into a trip that normally takes only an hour and a half, traffic slowed down for a roadblock up ahead. The Syrian civil war had been raging for over two years at this point and it was not uncommon for security checkpoints to spontaneously appear as the government hunted down members of the rebel forces.

But this was not a government roadblock. The fluttering black flags made clear to the passengers on the bus who were operating this checkpoint. Following the direction of the armed men, the bus pulled off to the side of the road for inspection. The black flags’ white script was now legible: دولة الاسلام في العراق والشام (Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant).

The travelers on the bus stiffened and put themselves in ‘careful mode,’ as Mahmoud would later call it. At that point, ISIS was only a minor player in the multi-sided war in Syria and had not yet demonstrated the brutality it later became known for.

Two armed ISIS fighters boarded the bus and began inspecting passengers paying particular attention to military-aged men. One approached Mahmoud and asked for his identification card. Once produced, the fighter scanned the card for a moment and handed it back. He then saw Mahmoud’s laptop backpack in the overhead rack and asked, “whose bag is this?” Mahmoud said it was his as the fighter took it down and began rummaging through it. In the bag, he found Mahmoud’s passport and began flipping through it. His eyes lit up when he found a stamped Chinese visa on one of the pages.

Mahmoud had traveled to China two months prior. As was the case for developing countries around the world, the telecommunications infrastructure of Syria was built primarily using low-cost Chinese equipment. As a heavy user of Chinese gear, Syria Telecom had the opportunity to occasionally send engineers to China for advanced training and Mahmoud was the latest to make the trip.

Holding his passport, the ISIS fighter asked Mahmoud, “what were you doing in China?” He responded that he was an employee of Syria Telecom and traveled there for work. Interest peaked, the ISIS fighter intensified his search through the bag. He pulled out Mahmoud’s laptop and ordered him to unlock it. From his seat on the bus, Mahmoud entered his password into the lock screen and handed it over. The ISIS fighter went straight to the MyPhotos folder and began flipping through the pictures.

In the middle of the bus full of passengers frozen with fear, the ISIS fighter flipped through photo after photo on Mahmoud’s laptop including those from his recent trip to China. He stopped at a selfie Mahmoud had taken in front of a huge Huawei computing cluster he saw on a tour during his trip. The ISIS fighter had seen enough and told Mahmoud that he needed to exit the bus for further investigation.

Two rows behind Mahmoud, another man on the bus was being interrogated. After directing the man to unlock his phone, a second ISIS fighter was again flipping through the photos. Soon enough a damning image appeared — a photo of his wife without a hijab. He, too, was directed to collect his things and leave the bus.

Unsure what to make of what was happening, Mahmoud felt numb as he exited the bus with the other man. They were led to two separate cars and placed in the back seat. Another ISIS fighter placed a blindfold over Mahmoud’s eyes.

Blindfolded, he felt metal handcuffs snapping into place around his wrists. It was at this point that Mahmoud felt a wave of terror wash over him. “What are you doing? We’re in free Syria!” Mahmoud shouted. “Shut up!” was the response from a man in the car as they drove away.

The Syrian outage of November 2012

By the middle of 2011, the Arab Spring uprisings were reshaping the region, having toppled long-standing regimes in Egypt and Tunisia. Attempts to stifle the anti-government protests, including a complete shutdown of internet access in Egypt, had thus far failed to slow the momentum.

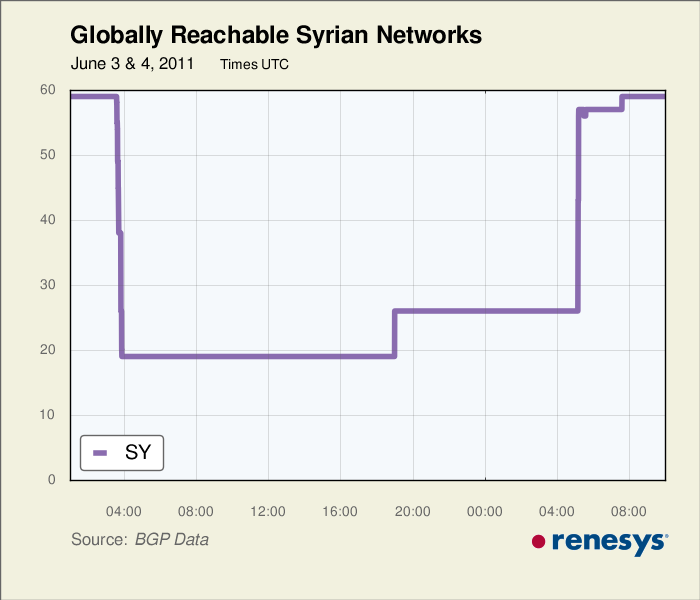

Protests in Syria had become violent and unresolved. Before long, Syria would have its first government-directed internet shutdown in early June 2011. At the time, I was an analyst with a small internet measurement startup called Renesys, who had been documenting the various shutdowns in the region earlier that year.

On that day we wrote:

Starting at 3:35 UTC today (6:35am local time), approximately two-thirds of all Syrian networks became unreachable from the global Internet. Over the course of roughly half an hour, the routes to 40 of 59 networks were withdrawn from the global routing table.

The Syrian government had ordered the deactivation of networks supporting the mobile and broadband networks while leaving the networks belonging to the government and important industries online. Service was restored after more than 24 hours of blackout, but life would never be the same in Syria.

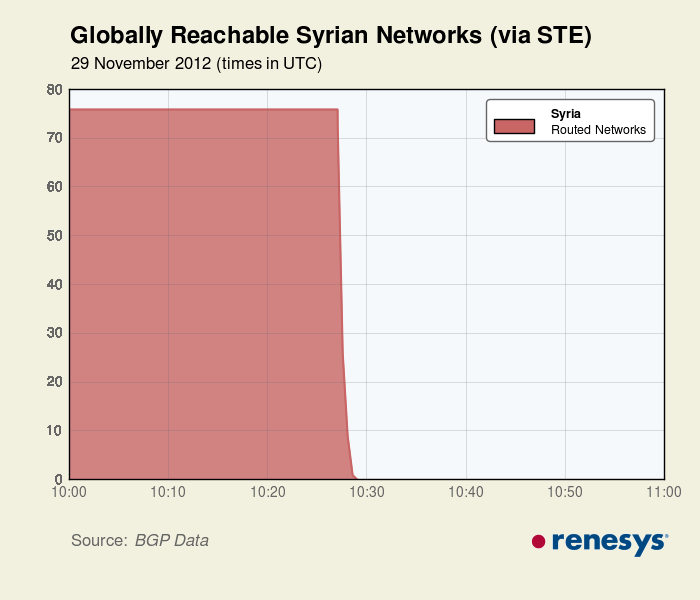

As the civil war in Syria raged into its second year, another outage knocked out internet across the country. Fresh off the heels of the government-directed outages of the Arab Spring the previous year, concerns quickly arose that this outage had also been intentional, directed by the embattled Assad government.

As we did with the outage from the previous year, Renesys reported technical details of the outage. We shared the timing of the withdrawn routes visible in our BGP data, illustrating it with the graphic below.

In our write-up on the outage, we expressed concern about the possibility of an intentional outage meant to hide some nefarious activity, but, ultimately, there was no way to tell strictly from the data whether it had been directed by the government or the result of a technical failure of some sort.

The outage was widely covered in the media and another internet company went further to claim that they could tell that the outage was intentional because the country had multiple points of egress — surely they could not have all failed at the same time. Coverage generally placed those juicier claims ahead of our more circumspect analysis — such is the world of breaking news coverage.

The Syrian government, for their part, blamed “terrorists” (their term for the rebel forces) for cutting a cable in Damascus causing the outage.

Regardless of the cause, internet service in Syria was restored several days later and the outage largely fell from the headlines until an interview with NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden appeared in WIRED magazine almost two years later.

Like the Day of Judgment

10 December 2025

In a cover story for the August 2014 issue, the NSA chronicler James Bamford wrote a lengthy piece based on a wide-ranging interview with the former intelligence contractor. Among the numerous bombshells in the interview, Snowden shared with Bamford the story that a US intelligence officer told him while he was working at Booz Allen in the spring of 2013.

The officer told him that the TAO (Tailored Access Operations) division, NSA’s elite team of hackers, had attempted to install an exploit into one of Syria Telecom’s routers that would have given the NSA the ability to intercept the country’s communications. However, in the course of the hack, the story goes, they inadvertently took down the router and with it all of Syria’s internet communications.

Bamford concluded the second-hand anecdote:

Fortunately for the NSA, the Syrians were apparently more focused on restoring the nation’s Internet than on tracking down the cause of the outage. Back at TAO’s operations center, the tension was broken with a joke that contained more than a little truth: “If we get caught, we can always point the finger at Israel”.

The anecdote fit well within Bamford’s feature story: another bad act by the NSA revealed by Snowden. If you are at all familiar with this outage, this is probably the version of the story you know. In fact, in the 2025 spy thriller Black Bag, the fictional intelligence operatives boast about spy agencies causing the outage over dinner.

When I was first connected with Mahmoud, he was still working as a senior engineer at Syria Telecom. He wanted to fill me in on details that outsiders had missed about what was happening in the country. I asked him about this particular outage and he remembered dealing with it.

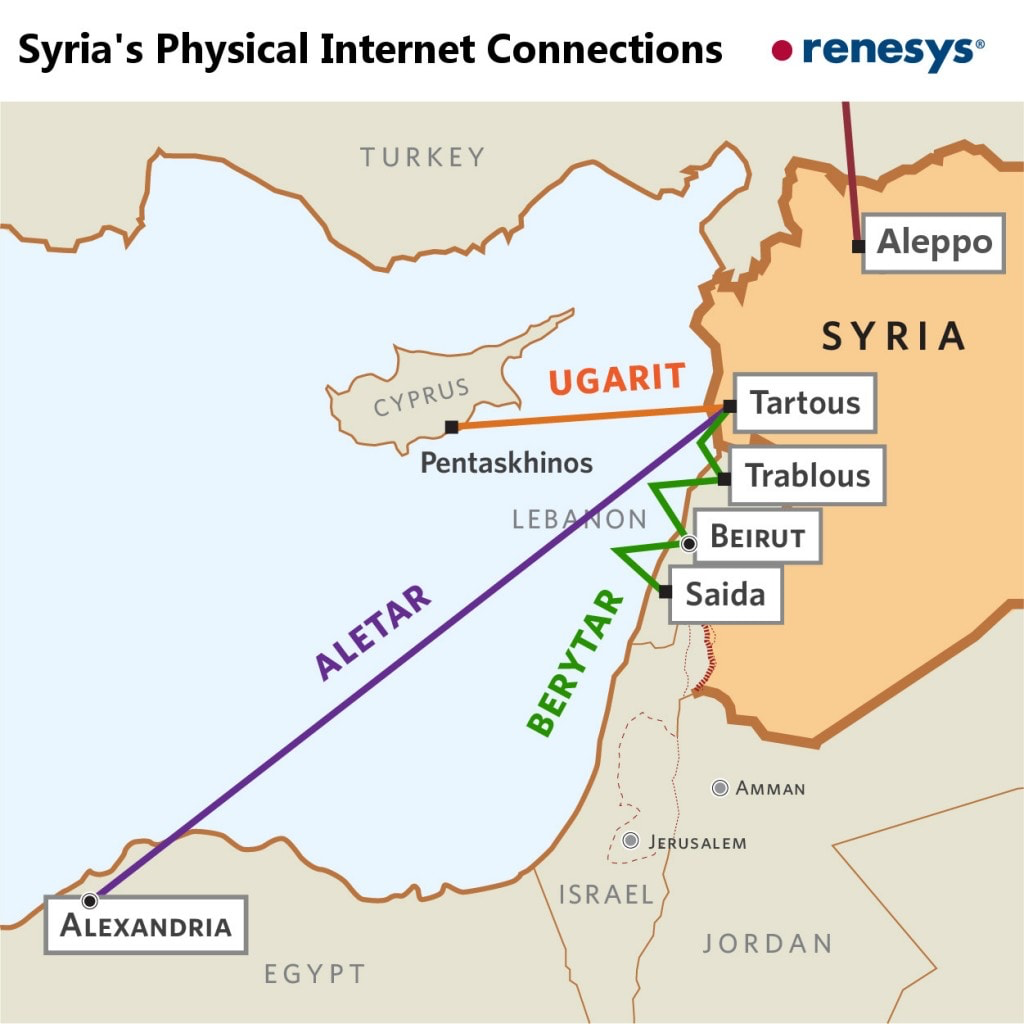

He explained that between 2004 and 2024, Syria Telecom relied on centralized distribution of internet service — the circuits to Turkey, Jordan and the submarine cables at Tartous terminated in a single facility on Al Thawra Street in Damascus. So much for the theory that multiple egress points meant a total outage could only be the result of a deliberate act.

By the fall of 2012, Syria Telecom (then called STE) had lost circuits that provided some redundancy for its connections to the outside world. By November 2012, all Syrian internet connectivity was reliant on a single 400km DWDM route from Damascus to Homs to Tartous. If anything along that route went down, all connectivity would be lost.

According to Mahmoud, on 29 November, one of the links in the path lost power — an increasingly frequent occurrence as fighting touched many parts of the country. The outage took down the circuit and with it the country’s internet connectivity.

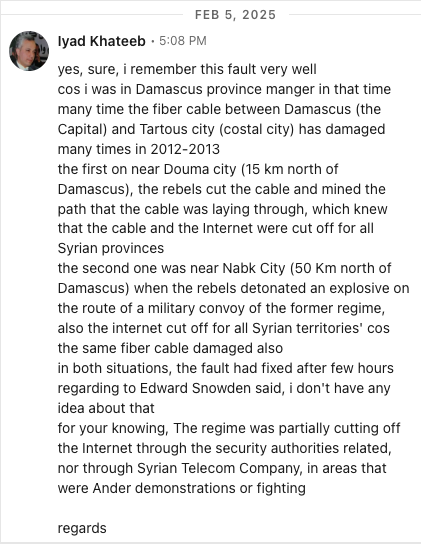

Following the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, I began pulling together the details to write this article. Searching through LinkedIn for additional sources, I sent a friend request to Assad’s final Minister of Telecommunications, Iyad Khateeb, who had just updated his profile, adding an end date for his term in the recently toppled government.

I asked him about the November 2012 outage and this was his response to me:

Was it Snowden’s hearsay about NSA meddling gone awry, or a simple power outage along a critical fiber path? A government-directed outage or a fiber cut by rebels? The lesson for me as an analyst at the time was to tread carefully when coming to conclusions from the other side of the world — those closest to the events were most likely to have the best knowledge of them.

---

Cuffed and blindfolded since being arrested at the checkpoint, Mahmoud sat stunned in the back of a car driven by two ISIS fighters. Eventually they arrived at a building where Mahmoud was pulled from the back of the car, and thrown to the ground in an empty room. He never again saw the man from the bus who had a picture of his wife on his phone.

They took off Mahmoud’s handcuffs and blindfold and he sat on the floor unsure of what would happen next. He spent the rest of that day and night alone in the room until more ISIS fighters woke him up in the morning to move him to a different location.

Again a blindfold was placed over his eyes and handcuffs on his wrists. He was dragged out of the building and thrown into the back of another car. After some time in the car they arrived at a larger ISIS site. It was a large prison, the ISIS version of Syria’s notorious Sednaya Prison.

Mahmoud was dragged into a room with a 16-year-old and a terrified boy, not more than 10 years old. He spent the rest of the day in the room handcuffed. By the evening, he had had enough and asked the guards to remove his handcuffs.

An ISIS fighter from Tunisia came into the room. Mahmoud asked to be uncuffed.

In response, the Tunisian tersely challenged Mahmoud, “how many units of prayer are there in Eid prayer?” testing his knowledge of Islam.

“It is two” Mahmoud responded confidently.

“You are very good”, responded the Tunisian.

“Then unlock my cuffs”, Mahmoud pleaded. And the Tunisian removed his handcuffs.

The following day, men came into the room and placed handcuffs and a blindfold on Mahmoud. They dragged him down a hall to an interrogation room. He was placed in a chair and had his blindfold and handcuffs removed.

A man entered the room: the interrogator. He knew enough about these situations that, despite having the blindfold removed, it was important to never look directly into the eyes of the interrogator.

Walking purposely toward Mahmoud, the interrogator pulled out a large knife and quickly brought the blade to Mahmoud’s throat.

“I will kill you! You are Shia!” the interrogator screamed, pressing the blade against the front of Mahmoud’s neck.

Terror made Mahmoud bold, he screamed in response, “if you kill me, my blood will be haram for you forever”. It was a desperate appeal to the religiosity of the interrogator.

“You don’t know haram. You don’t know Islam” responded the interrogator who was a small man with a slight build. He spoke with a Damascus accent and was young, not more than 22 years old.

Mahmoud pleaded his innocence, “I am a civilian worker. I am like an electricity worker. I am responsible for the internet”. Around this time, most people in Syria didn’t care that deeply about the internet. It was seen as an entertainment service to play video games and watch movies.

Syrians in Gaza are displaced, killed, and missing under the rubble

14 March 2024

After two or three minutes of this back-and-forth, the interrogator took the knife away. The entire interrogation lasted between 30 and 45 minutes before he was blindfolded and led back to his room.

The following day he was again brought to an interrogation room where all of his electronic devices were laid out on a table. An interrogator ordered him to remove the passwords from every device. He removed the password on his iPhone 4, then removed it from his laptop.

They had also found an external hard drive that Mahmoud had picked up while in China. It was password-protected, but the password came with the device and couldn’t be changed. He told them he can only give them the password, so they wrote it down with information about Mahmoud on a piece of paper and taped it to the drive.

He would never see any of these devices again but almost two years later he received a call out of the blue about the Chinese hard drive. The caller explained that he was a Kurdish fighter with the PKK and they had just killed some ISIS fighters in a small Syrian town (Kobane or Ain Al-Arab عينالعرب).

The Kurdish fighter said one of the ISIS fighters was using the hard drive. They found his contact information on it but not the password. Over the phone, the Kurdish fighter demanded he tell him the password, to which Mahmoud responded, “Fuck you!” and hung up the phone.

A Rejected Ransom

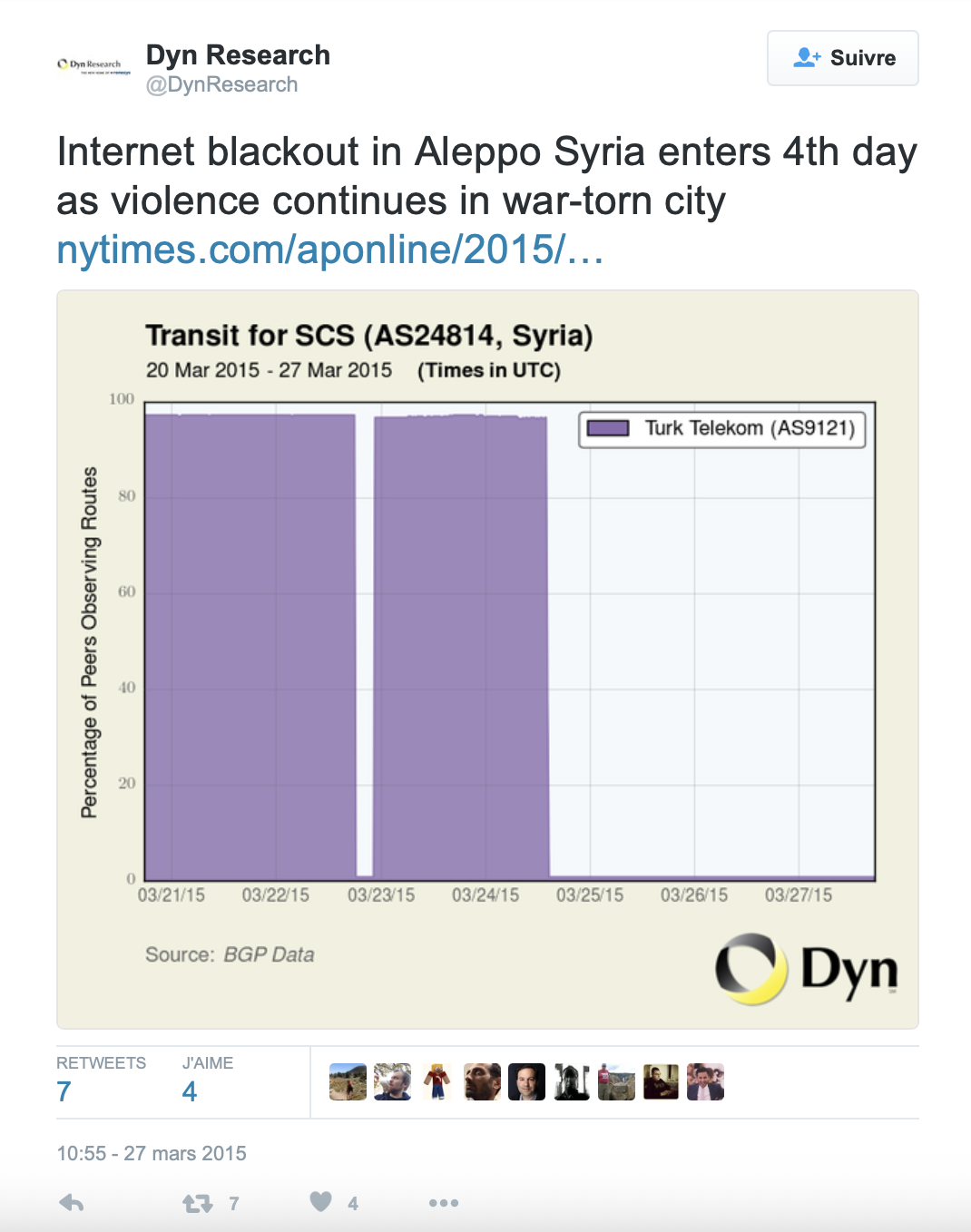

By 2016, Mahmoud and I were in regular contact after becoming connected through social media. That year he helped me, from inside Syria, draft an update on the country’s state of internet connectivity: a new fiber optic line had been installed to replace the high-capacity microwave link connecting Aleppo to the internet via the coastal city of Latakia.

Mahmoud and his fellow engineers had set up a connection to restore service to northern Syria after ISIS had destroyed a critical piece of infrastructure in Saraqib back in August 2013, two months earlier.

The new connection restored service to Aleppo using a hastily installed fiber circuit to reach Turk Telekom via Idlib, Syria. The link was activated at 14:45 UTC on 8 October 2013 and would last until March 2015.

In that month, Mahmoud was summoned to a meeting of the management of Syria Telecom. The city of Idlib had just fallen into the hands of the rebels as part of a 2015 spring offensive. The attendees wanted Mahmoud to explain the implications of losing a core piece of telecom infrastructure in Idlib. In an audacious move, the rebels had demanded the Assad government pay them a ransom to leave it intact.

After brief consideration, the Syrian government rejected the demand, the rebels blew up the equipment, and Aleppo and northern Syria lost internet service once again.

Internet service in Aleppo would only reappear in November 2015 after Syria’s government military forces, aided by a new Russian bombing campaign, made the territory safe enough for Syria Telecom engineers to reconnect Aleppo using a high capacity microwave link to the coastal city of Latakia, Syria.

In October 2016, the microwave link was replaced with a new fiber optic cable (1).

---

On his third day in the ISIS prison, Mahmoud was again dragged out of his room and down the hall for another interrogation.

“What do you want?” he asked his captors, exasperated and beginning to feel desperate.

The interrogator said ISIS wants to control the Syrian national internet network from the prison.

“You cannot”, Mahmoud replied, “we can go to our NOC in Aleppo” using the acronym for Network Operations Center, the control center of an ISP, “but from here, you cannot”.

The interrogator was not impressed. He wanted useful information from Mahmoud.

“I will help you”, Mahmoud relented, “I will give you good information. You can’t control the internet from here, but you could cut off service to Aleppo”.

The interrogator was now listening.

Mahmoud explained that there was a small Syrian village called Saraqib, which was in ISIS territory. If they found the facility with the telecom equipment, they could cut off service to the northern parts of Syria under government control including Aleppo, the country’s largest city.

The outage could hinder the “regime and its military” Mahmoud explained, hoping this information might spare his life. There was no reaction from the interrogator.

Without any further discussion, he was brought back to his room. For three days he was left alone. He seemed to now be getting better treatment. He was fed three times a day. No blindfold and no handcuffs.

Only after he was freed did he learn that during this period, ISIS had sent fighters to find the telecommunications equipment that Mahmoud had described. Once found, the critical fiber optic cards were pulled out of the routers causing an extended internet outage in northern Syria.

On his fourth and fifth days inside the ISIS prison, a new interrogator pressed him for more information about the telecommunications network of Syria. The interrogator said that he used to work on the mobile network for SyriaTel.

“Write down everything you know”, he ordered Mahmoud and handed him a blank notebook.

Mahmoud began filling the pages with copious amounts of useless technical information. All the while he thought about the contents of the Chinese hard drive they took from him, which contained encyclopedic details about the entire telecommunications network of Syria including router configurations and passwords for nearly all of the Syria Telecom’s core equipment. ISIS never understood the trove of data they had on that device.

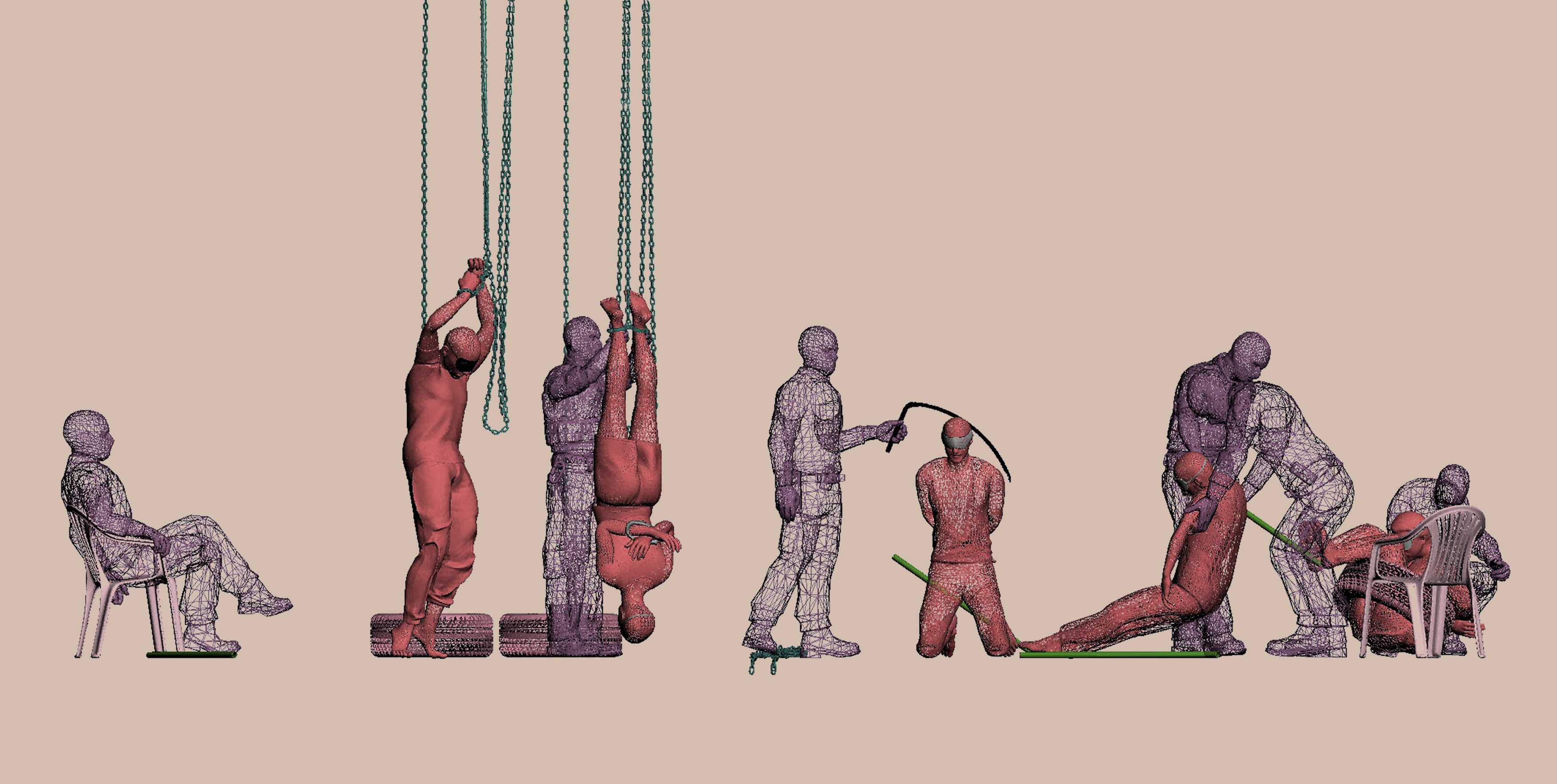

Day after day, he continued filling the notebook. As he wrote, he couldn’t help but listen to the muffled screams from detainees in the makeshift prison. He could only imagine what they were going through.

After more than two weeks in captivity, men entered his room looking for him. It was 10pm. From his time in the prison, he had learned some of the patterns of behavior of the guards. Those few prisoners who were released were taken in the morning. To be taken at night, usually meant execution.

“Close your eyes” the guard barked at Mahmoud.

“Why?” Mahmoud asked.

“You will leave with us right now”, the guard said as he dragged Mahmoud to his feet.

Mahmoud became very scared. “I don’t want to go at night! Let’s go in the morning”.

“Shut up! Shut up!” the guard screamed, “you cannot discuss this with me. You leave now or never”.

Mahmoud put his blindfold on and followed the guard outside.

Another guard behind him said, “here is your identification card and 2000 Syrian pounds.” A sum roughly equal to $20.

“What about my things? My laptop and my phone?” Mahmoud asked.

“Shut up! The court ruled this”, the guard responded.

“I didn’t see any judge”, Mahmoud responded again feeling desperate.

“Shut up!” the guard yelled.

“What is the name of the court? I want to object to the court” Mahmoud pleaded.

“Shut up and take your card” was the response.

They were standing beside a car. The guard told the driver, “this guy talks too much. If he talks to you, shoot him in the head and dispose of him". The driver acknowledged.

Still blindfolded, Mahmoud got in the back of the car and it pulled away into the darkness of night.

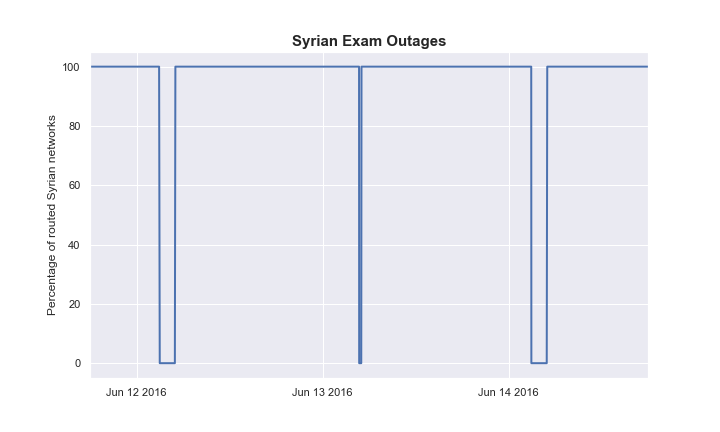

The Syrian student exam shutdowns of 2016

Early one morning in June 2016, the manager for the networking team at Syria Telecom was called in for a meeting in the main facility in Damascus. Present at the meeting were members of the Syrian Ministry of Education, Syrian Ministry of Telecommunication and an officer from the Telecom Management division of the Syrian Military Intelligence Directorate. They explained to the manager that in the coming days Syria Telecom was going to need to disable internet service nationally to combat cheating on high school final exams.

The national outages would take two phases. In the first phase, links to the outside world needed to be disabled in the hours prior to the exam as test materials were physically distributed around the country — or at least the parts of Syria still under Assad’s control. In the past, the paper exam materials would often be intercepted, copied and spread on social media or other communication services, compromising the exams.

Once the exams began, the second phase would begin. At that point, international links would be restored, but mobile data service would be disabled to prevent the use of handheld devices to cheat. Once the day’s exam was over, everything would go back to normal.

The manager then called Mahmoud in and gave him the task of implementing phase one: take down Syria’s internet connections to the outside world in the hours before the exam. Mahmoud drafted a set of pre-defined commands to run on Syria Telecom’s gateway routers that would cause them to stop announcing the country’s routes in their BGP sessions with international carriers. This would effectively remove Syria from the internet’s global routing table. By removing these routes, internet traffic could no longer find its way into Syria and would be dropped. Since most internet traffic relies on two-way communication, disabling one side of the connection would disable nearly all of the internet connectivity with the outside world.

The intelligence officer explained to the networking manager the sequence of events. He would receive a phone call at 11pm the night before the outage directing him to take down the internet service. He advised the manager to be ready to act as directed. The manager responded that they would be ready.

As the day of the first exam approached, everything went as planned. The manager received a phone call in the late evening to take down the internet the following day. In the morning, he directed Mahmoud to run his router commands and Syria was disconnected from the internet. Once the exam began, another script restored the routes in BGP, re-enabling internet communication for the country (2).

The subsequent internet blackouts unfolded the same way until the evening of 12 June 2016. According to the schedule, there was supposed to be an outage the following day, but the manager never received the late night phone call ordering the shutdown.

The following morning, Mahmoud texted the manager to ask what they should do. The manager was steady, “just wait. We don’t do anything until they tell us to do something”. So they waited.

Finally the manager’s phone rang, but it wasn’t the intelligence officer from the Telecom Management directorate calling, it was Syria’s Minister of Telecommunications who had just received a frantic call from the Minister of Education. “Why the hell haven’t you taken down the internet?” he raged, “We have an exam about to begin and you aren’t following the plan!”

Shaken, the manager responded that he had been directed to wait for a phone call to which the minister responded, “well consider this the fucking phone call! Turn off the goddamn internet!” As soon as he got off the phone, he gave Mahmoud the go ahead to pull the plug and service across the country dropped out — an hour and a half later than originally planned.

Illustrated above, the delay of the Syrian internet shutdown on 13 June 2016 is forever preserved in historical BGP data, although the story behind the delay has never been told publicly until now. And it doesn’t end there.

Later that day, the manager called Mahmoud to tell him that he had been instructed to immediately come to Syrian intelligence’s Telecom Management office in Damascus. He departed and shortly after, his mobile phone was disconnected. After a while, Mahmoud called his CTO and told him what had happened. The CTO explained that the manager had been arrested and taken in for interrogation.

When he returned the following day, he explained that he had been interrogated for hours by the military intelligence officers. Among other things, they demanded to know who told him to disable Syria’s internet on 13 June. He explained to them how he received a direct call from the telecom minister, to which they roared, “You don’t ever do anything unless we tell you to do it”.

The only reason he was able to get out that same night was because he had a relative in the president’s office who had heard about the situation and called the Telecom Management office of the Syrian Military Intelligence to vouch for the directive from the education minister. The Telecom Management office wouldn't even answer the call from the Minister of Communications himself.

After the manager’s detention, Mahmoud feared being the next to be arrested by Syrian intelligence, and without a relative in the president’s office like his manager, he might not be released as quickly, if at all.

It was at this point that Mahmoud decided it was time to make a plan to leave Syria or he might find himself in an impossible situation like his manager was.

—--

From the accents, Mahmoud could tell the two men in the front seats of the car driving him away from the ISIS prison were Tunisian.

They played a recording of the Koran, mimicking every word like they were in a trance. Mahmoud was very scared. He became convinced that this would be the end of his life.

After 30 minutes of driving, the car stopped. The driver ordered Mahmoud to get out of the car.

“Don’t raise your head until we drive away”, he instructed Mahmoud.

He got out and immediately pulled off his blindfold. The car, either black or dark blue, sped away. He was surrounded by total darkness. There were no cars and no buildings.

An attempt to understand violence in the new Syria

15 December 2025

He picked a direction and began walking down the road. Hours later, he eventually came upon a small rural village.

Upon entering the village, he encountered a man. Mahmoud explained what happened to him and asked where they were. The villager, an older man, was suspicious of the stranger entering his village so late at night.

“Can I get a car to drive me to Idlib?” Mahmoud asked.

“It’s too late”, replied the man, brusquely.

“Well, where can I find a mosque to sit down or lay down?” Mahmoud asked.

“That way”, replied the man motioned to the center of town.

As Mahmoud walked toward the mosque, he encountered another man who asked him what had happened. He explained that his name was Ali and he would make sure Mahmoud got home.

Mahmoud walked with Ali back to his house where some of Ali’s family members had been awoken by the talking. Ali explained that he would be helping Mahmoud get back to his family. His family urged Ali to bring a gun if he was going to drive so late at night.

Ali announced that he would not be bringing a gun because he would be safe. He was taking care of Mahmoud for Allah.

Mahmoud got in the car with Ali and started driving. Mahmoud wanted to call his father but they needed to drive for several miles before they could get a mobile signal. Eventually he reached his father using Ali’s phone. His father was overjoyed to hear from him.

His father said that he had heard he was taken by ISIS but was unable to get any further information about his whereabouts or condition.

His father ran to his car and started driving towards Mahmoud and Ali. They met at the midpoint and Mahmoud ran from the car and embraced his father.

Back in Aleppo, communications were down. Likely due to the disconnection of the equipment in Saraqib that Mahmoud had detailed during his interrogation. Someone had informed his manager that Mahmoud had been taken by ISIS and was probably providing them information.

Mahmoud became scared that he might be arrested by the Syrian military intelligence service next. So he reached out to some trusted contacts in Aleppo to check to see if there were any arrest warrants for him before returning. There were none.

After he returned to Aleppo he was visited by a Syrian military intelligence officer who directed him to write up a report on his captivity by ISIS. He did, leaving out the part about sharing the location of the equipment in Saraqib. He paid a bribe to the officer to not look too deeply into the matter and that was the end of it.

Internet Analysis Meets American Foreign Policy

Following our coverage of the internet shutdowns during the Arab Spring in 2011, Renesys developed a number of contacts in the US government and the digital rights community where we could privately share information that might aid efforts to maintain internet access in dangerous places around the world.

Among the items passed along to contacts in the summer of 2013 was observation that internet service in the city of Aleppo appeared to go down when Syria Telecom lost its connection to Turk Telekom. These outages didn’t show up in the usual indicators — BGP withdrawals or fewer devices responding to pings. However, it is not unusual that some types of outages don’t surface in those datasets.

The presence of the Turkey connection in publicly available data could be used as a proxy for outsiders whether this Syrian region is online — a potentially useful tip for our contacts monitoring Syria. After sharing this information, we got an immediate response from a US government contact along the lines of, “could you publish that on your blog? Like, as soon as possible?”

I agreed to write the post. It wasn’t that out-of-the-ordinary for me, as we had been covering the situation in Syria for multiple years. That evening, I wrote up my analysis on the outages in Aleppo and, in the morning on 30 August, we published it.

As soon as it went online, I got a phone call from the Washington Post. They had received a tip of a widespread outage in northern Syria and saw that I had just written something about the topic. Service had gone down again the previous evening — I hadn’t checked the current status before publication, otherwise I would have mentioned it in my piece. I had mistakenly assumed that I wasn’t breaking any news.

Within a couple of hours, the Post published a story about the outage of Aleppo citing the blog post I had just written. We added an update to the top of our post linking back to their article and I moved on to work on other things.

However, the following day on 31 August, President Obama would announce that he was seeking congressional authorization for military action in Syria, sending Congress draft language the same day. After the announcement, the White House mounted a coordinated push — both on Capitol Hill and in public — to win approval. This included releasing declassified intel and sending cabinet officials to appear on Sunday shows and to testify on Capitol Hill.

The sequence of events got me wondering. Over the weekend, I sent the reporter a message asking the nature of her source that triggered her story; was it someone in Syria, or Turkey maybe? She responded that it was someone in the US government. Was it the same that triggered mine? I didn’t pursue it further.

Ultimately the effort to attain congressional approval for military action in Syria failed, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that we may have been manipulated to help drum up some additional negative headlines — albeit accurate — about Syria ahead of the President’s request for congressional support for military action.

And it was centered on the outage likely caused by information provided during the ISIS captivity of my future insider and technical source.

—

After leaving Syria, Mahmoud found network engineering work with a small ISP in a city with the help of fellow Syrian refugees. He married a woman he met over Tinder, “modern romance” he told me with a wry smile. She had also fled Syria and together they are now raising two young children.

Over the years, I would ask Mahmoud if I could write about his experiences described in this article. He had been hesitant due to concerns about the safety of family left behind in Syria, even his own well-being outside the country.

When the Assad regime was toppled a year ago, we exchanged a flurry of messages. “Assad is gone! We are free right now!” he wrote to me with joy. When I asked about the possibility of writing his story now that Assad was deposed, he responded, “hi Doug, yes, yes, you can write. Assad is gone and we are free

!”

!”

(1) From a BGP standpoint, the development was marked by the retirement of AS24814, which had served Aleppo and the surrounding region for the previous three years.

Due to the fact that Syria Telecom’s national network had been cut into two disjoint pieces, the new service in the north had to make use of a previously unused ASN (24814) registered to the Syria Computer Society, or risk not being able to connect to the rest of the telecom’s network.

Had they used Syria Telecom’s ASNs (AS29256 or AS29386), the routers in the company’s main network, serving Damascus and other cities, would have rejected the routes as per BGP’s loop prevention mechanism, since they were being received through international connections.

The link was activated at 14:45 UTC on 8 October 2013 and it was then that AS24814 was first employed, designating the emergency communications connection for northern Syria.

When the microwave link was replaced with a new fiber optic line, the BGP routes handling service for Aleppo was migrated from AS24814 to Syrian Telecom’s AS29256, where it remains today. AS24814 was never seen in the global routing table again.

(2) Removing Syria’s BGP routes prevented inbound traffic, but no effort was made to explicitly block outbound traffic. Part of the rationale for this approach was that there were a few important networks that needed to stay connected and therefore needed to continue sending outbound traffic.

The resulting outages were therefore asymmetric and led to curious side effects like surges of outbound DNS traffic. Riding over a connectionless protocol, DNS doesn’t require a two-way exchange to send a query, but with no BGP routes to guide the response messages, the answers never arrived.

Having not received responses to their previous queries, internet-connected devices across Syria would resend and resend and resend their queries, resulting in a flood of outbound DNS queries. Here is a graphic of DNS queries received from Syria by DNS operator Dyn around the time of a Syrian exam shutdown. The surge in query volume was a consequence of the implementation of the shutdown which allowed traffic to exit but not enter the country.