(Latakia) While the city of Latakia experienced long hours of anxiety on the night of the fall of the Assad regime on 8 December 2024, the smoke carried by the north wind reached Dima's house, causing her to suffocate slightly.

From the window of her small kitchen, she watched sadly and silently as the flames engulfed the cigarette factory known as Regie, located near the bus station in Latakia. She had spent ten years of her life there, before Decree No. 2533, issued by the General Secretariat of the Presidency of the Republic on 27 August 2025, ended any remaining hope for her and more than 10,000 workers contracted by public sector companies and institutions.

"We received the news at the factory while sitting under the trees. Honestly, without exaggeration, three women fainted when they heard the decision", says Dima, previously forced to take unpaid leave and receiving only one salary of $28 (280,000 Syrian pounds, the fifth category, the lowest level of the career ladder).

On the night the regime fell, Dima did not realize that the fire she saw would destroy her job and those of her colleagues, even though she knew from the intensity of the smoke that it was unlike previous fires that had struck the institution. It was not the only one, as it was followed by another fire at the same time in the tobacco paper storage warehouses at the Latakia port near the Syriatel company. One of the workers said of the fires, “May God burn the heart of the one who burned the factory. They burned more than just the factory; they burned our hearts, because in the end, we are the ones who will pay the price”.

The production warehouses near Tishreen University were stormed, their iron doors broken down and looting began as a vengeance. The scene of the attack was surreal: cars, motorcycles, and individuals carrying as many cartons of “Al-Hamra Al-Tawila,” , “Al-Qasra,” “Al-Sharq,” and other types of cigarettes discontinued by the company. In the months before the fall of the regime they had been distributing a limited number of cartons of national tobacco specifically to merchants and public and private institutions (in small quantities).

In the days following the sudden fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime, the streets of Latakia were filled with hundreds of stalls selling national tobacco, and the products were sold for nothing. Dima watched silently, wondering about her future and that of 4,000 other families after this devastation. A few kilometers away, while the production facilities were burning, another tragedy began when others stole spare parts from the “Reedring” (drying factory belonging to the same tobacco company near Saqoubin, 2 km north of the city of Latakia): they ignored that this institution, which was burning and being looted, had served the people to the best of its ability.

"Those who burned or looted drove a nail into the coffin of Syria's largest production institution. What happened at the drying plant in Latakia was a systematic theft of spare parts and valuable equipment, as if someone were working to ensure the final death of this giant edifice, which is over 100 years old", says engineer Muhammad al-Hussein, from the management of the institution for Syria. Samar Bayhas, a third-year law student at Tishreen University, who is contracted to the factory, points to the reading room and says, “Whoever stole the small electronic parts for the factory machines knows exactly what they stole”.

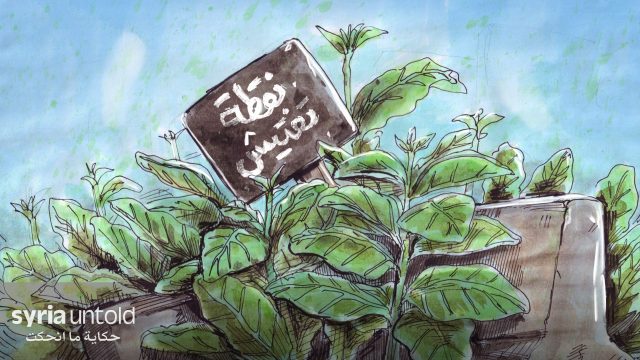

Syrian tobacco... a long story

Tobacco cultivation and manufacturing began in Syria in the 18th century, in response to colonial industrial expansion. With the French Mandate in 1918, its cultivation and export continued until the “Tobacco and Tobacco Monopoly Administration” was established in early 1935 in Syria and Lebanon under French supervision, according to Youssef al-Hakim in his book Syria and the French Mandate, which later became known as “Regie.” This institution continued to absorb the efforts of farmers and workers and export raw tobacco to France until its nationalization in the 1950s, as stated in the book The Formation of a Republic by Muhammad Hawash.

The workers of this institution, along with those in the textile and leather industries, formed the basis of the working class in Syria. The workers of the Regie staged one of the most famous strikes in the history of the Syrian labor movement, with more than 200 workers gathering on 3 June 1935, starting from Bab al-Sariya in Damascus, along with their wives and children in a noisy demonstration. They were shouting: “We are hungry, we want to eat, we want bread, we want flour”. They were joined in their strike by textile, shoe, and leather workers in Damascus and knew their financial and industrial value. Without them, the machines will not work, and it is not easy to find replacements, so we can guess who did it”.

In its final years, the tobacco industry employed thousands of workers directly, not to mention thousands more in the economic chain, including farmers, traders, manufacturers, and others. Economically, tobacco is ranked as the third most important agricultural crop in Syria after wheat and olives, and is a primary source of income for many rural families in the coast, the Ghab Plain, and the countryside of Aleppo and Idlib. Due to the scattered nature of the cultivated areas, tobacco factories were established in Aleppo, Tartus, Latakia, Jableh, and Qardaha. According to figures from the Syrian Ministry of Industry, the value of tobacco production for the 2021-2022 season reached 7,572 tons, worth 30 billion Syrian pounds, from an area of 95,000 dunams, while estimated profits reached 18 billion Syrian pounds (equivalent to $1,3 million).

Latakia alone accounts for 3,400 tons of the total production, which is approximately half of Syria's total production. From this, we can understand the magnitude of the loss suffered by the Syrian Coast, as no tobacco leaves were purchased from its farmers this year. According to farmers in the villages of Banias (Bustan al-Hamam, al-Anaza, and others), only a small portion of the crop was harvested, while hundreds of tons of tobacco leaves were left uncollected, according to farmer Mamdouh Ibrahim from Bustan al-Hamam. This year, “we only planted tobacco seedlings for local consumption, enough to meet our needs”.

After the fires and thefts, the cigarette factory and some of the Reedring departments in Latakia shut down. For more than seven months, Dima went to work to sit with hundreds of others in the factory courtyards without actually doing any work, because “attendance is mandatory and any day of absence could be grounds for dismissal”, says the 40-year-old woman.

During her years of work, Dima raced against time, waking up early every day to get to her shift in the paper department. She quickly changed into her work clothes in the changing rooms and dove into a daily battle with tobacco paper (Abu Reiha and Virginia), removing it from hemp threads and arranging it in layers upon layers. These types are the most commonly used in the Syrian tobacco industry. When she finished, other workers would transfer it to the shredding department, where it was turned into what is known as “shredded tobacco” before being transferred to the fermentation oven. Dima and hundreds of other women who performed the same manual labor would continue until 3:30 pm if it was a morning shift. Night shifts were also available. Some of them spent 15 years in this endless cycle.

Types of contracts and rights

Dima and hundreds of other employees like her were hired by Regie under temporary contracts, a system that began in Syria at least 15 years ago with the aim of supporting the productive sector with workers without the state having to pay additional costs such as insurance, medical treatment, and so on. Ms. Malak Mahmoud from the legal department at Regie explains the details of these contracts, telling SyriaUntold: "There are three types: annual contracts, approved by the Central Control and Inspection Agency, entitling the holders to a raise every two years, i.e. their salary increases by a certain amount calculated according to the state's basic labor law. Seasonal contracts, lasting three or six months, and daily contracts, which do not entitle the holder to any salary increase, job promotion, or any other rights such as medical care, incentives, or transportation". Furthermore, despite being the largest segment of the workforce, these workers are not entitled to regular meals. Similarly, productivity incentives used to be helpful at one time, but they have been discontinued for several years, according to Ms Mahmoud.

Latakia alone accounts for 3,400 tons of the total production, approximately half of Syria's total production. From this, we can understand the extent of the loss suffered by the Syrian Coast, as no tobacco leaves were purchased from its farmers this year. According to farmers in the villages of Banias (Bustan al-Hamam, al-Anaza, and others), only a small portion of the crop was harvested, while hundreds of tons of tobacco leaves were left uncollected, according to farmer Mamdouh Ibrahim from Bustan al-Hamam. This year, “we only planted tobacco seedlings for local consumption, enough to meet our needs”.

Dima confirms this: “We work on a contract basis, where every day is counted. All I know is that if they record me as absent for one day for any reason, my salary will be reduced by 20,000 pounds”.

Despite the dangerous nature of the work, the majority of workers in these departments are women, Malak explains. “During the last contract, most young men were in the army or fighting, so women had no choice but to compensate for their absence by working to earn a minimum wage that is not enough to live on for a week”. A quick count of the numbers in these departments, and not just at the Regie, shows that more than 90% of the workers are women between the ages of 20 and 60.

Health status before and after

Workers under these contracts perform the most arduous and difficult types of work for the lowest wages. Therefore, many people avoid these jobs, and only those who have almost no other options take them. Ms. Hind, 52, a mother of three, recounts: “I am 50 years old and suffer from high blood pressure, but I cannot even afford the medication. The noise from the machines, which sounds like the roar of an airplane, is the cause of my high blood pressure”.

Last year, as Hala E. recounts, one of the long-term contract workers who spent 13 years in the sorting department at Regie, their colleague Azhar, a worker employed on a three-month contract, had an accident that nearly cost her an eye: “The string holding the papers together got tangled. As she tried to untangle it, she forgot that she was holding a steel ruler in her other hand, and as a result of her sudden movement, she suffered a deep wound to her left eye”.

Military Reserve Business Thrives in Syrian Coast

25 October 2017

She received first aid at the company clinic, but it was not enough to stop the bleeding. The 40-year-old Azhar's cries and pain caught the attention of an engineer at the company, who volunteered to pay for her treatment at a private hospital out of his own pocket. Neither Dima's nor Azhar's salaries cover the cost of any emergency surgery even in a government hospital.

The Unified Labor Law in Syria does not completely negate the basic rights of temporary workers, but the scope of these rights differs from that of permanent workers, as their rights may be limited to what is stipulated in their employment contract or in the regulations of the public entities where they work. In general, temporary workers may not enjoy the same benefits and incentives as permanent workers, such as bonuses and annual raises, unless this is stipulated in their employment contract or in the regulations of the entity they work for.

In recent years, healthcare in the public sector has deteriorated significantly. Once a right that workers had fought long and hard to obtain, it has become a source of corruption and theft. Hala told us: “We are not entitled to healthcare because we are not permanent employees, even though we have spent at least ten years on the job and many of our injuries are work-related”. Wadi and others confirm this.

The final decision

With the shutdown of Latakia's factories, from spinning to weaving to cotton yarn, management began threatening to dismiss workers who were “idle”, as the branch manager of the cotton yarn company, who asked not to be named, told SyriaUntold. According to the branch manager, an electrical engineer, there is “payment of salaries for nothing, without any productivity”.

A decision was issued after the fall of the regime at the end of February 2025 to grant workers in a large number of government institutions three months of paid leave, which was then extended for another three months until August 2025.

The threats of dismissal, which workers feared, became a reality after the issuance of Decision 2533, which stipulates that “temporary contracts of any kind shall not be renewed upon expiration, except in light of public need and with the approval of the General Secretariat of the Presidency of the Republic exclusively”. This decree was not isolated, but came within the framework of what was called “government measures to improve the efficiency of the administrative apparatus”, which also included a freeze on appointments and a halt to the extension of services. A single decision affected all sectors of public industry—irrigation, spinning, weaving, and others—turning the tragedy of a burned-down factory into a model for a systemic crisis aimed at “rationalizing human resources” at the expense of the most vulnerable groups.

The Syrian Coast After the Fall of the Syrian Regime

10 January 2025

Despite the dangerous nature of the work, the majority of workers in these departments are women, Malak explains: “Over the past decade, most young men have been in the army or fighting, so women have had no choice but to fill the gap by working for minimum wages that are not enough to live on for a week.” A quick count of the numbers in these departments, not just at the Regie, shows that more than 90% of the workers are women between the ages of 20 and 60.

Dima says: “We received the news in the factory while sitting under the trees. Honestly, and without exaggeration, three women fainted when they heard the decision.” Dima was not alone. Dozens of her colleagues in the paper, drying, and sorting departments received the same notice. Women who had spent more than a decade within the walls of the factory, processing Syrian tobacco with their own hands, suddenly found themselves facing a closed door. Clause (c) was a death certificate for the dignity of thousands of families.

Hind commented on the decision: “Suddenly, my colleagues and I were in shock. Even those of us who were permanent employees were given paid leave, and those with three-month or annual contracts were also dismissed. What did we do wrong? We spent our whole lives doing this job, and this is how they rewarded us”.

Hundreds of appeals and protests by workers have been to no avail. Hind says: “A week ago, about a hundred workers went to the governor of Latakia, but it was useless. Everyone went and protested, but the decision has not changed and will not change”. She adds: “We have received other messages saying, ‘We are seasonal workers at the Tobacco Corporation and have been committed to our productive work for more than 16 years. We hope that the minister will renew our contracts’”.

“What should we do now?”

Dima, Hind, and Wazdar say: “Our salaries barely covered our expenses. The most important question is: What should we do now? I am 50 years old... What kind of job can I get?”

The women do not have the practical experience to start a new project or find a new job. In fact, hundreds of them have husbands who have probably joined the ranks of the unemployed. Ms. Souad (46 years old, married with two children) from the Qas al-Bawaki neighborhood, recounts: “I am the first among those who are helpless and unable to pay rent. I have a university student and a daughter in school, and my husband is unemployed. I am considering working for a doctor who needs a receptionist. I have used up all my savings, and my last paycheck was in June”.

While Dima and her colleagues search for a living in odd jobs, there are still unionists working quietly to mobilize unions in the Coast to protest and strike. However, there are many obstacles to overcome, including organization, which seems impossible given the current conditions in the Coast.

In light of this situation, the lives of female workers have turned into a daily hell. Fatima, 38, works as a house cleaner for two dollars a day. She says, “I work 12 hours straight, and sometimes I don't get paid in full. But what can I do? This is the last stop before begging”.