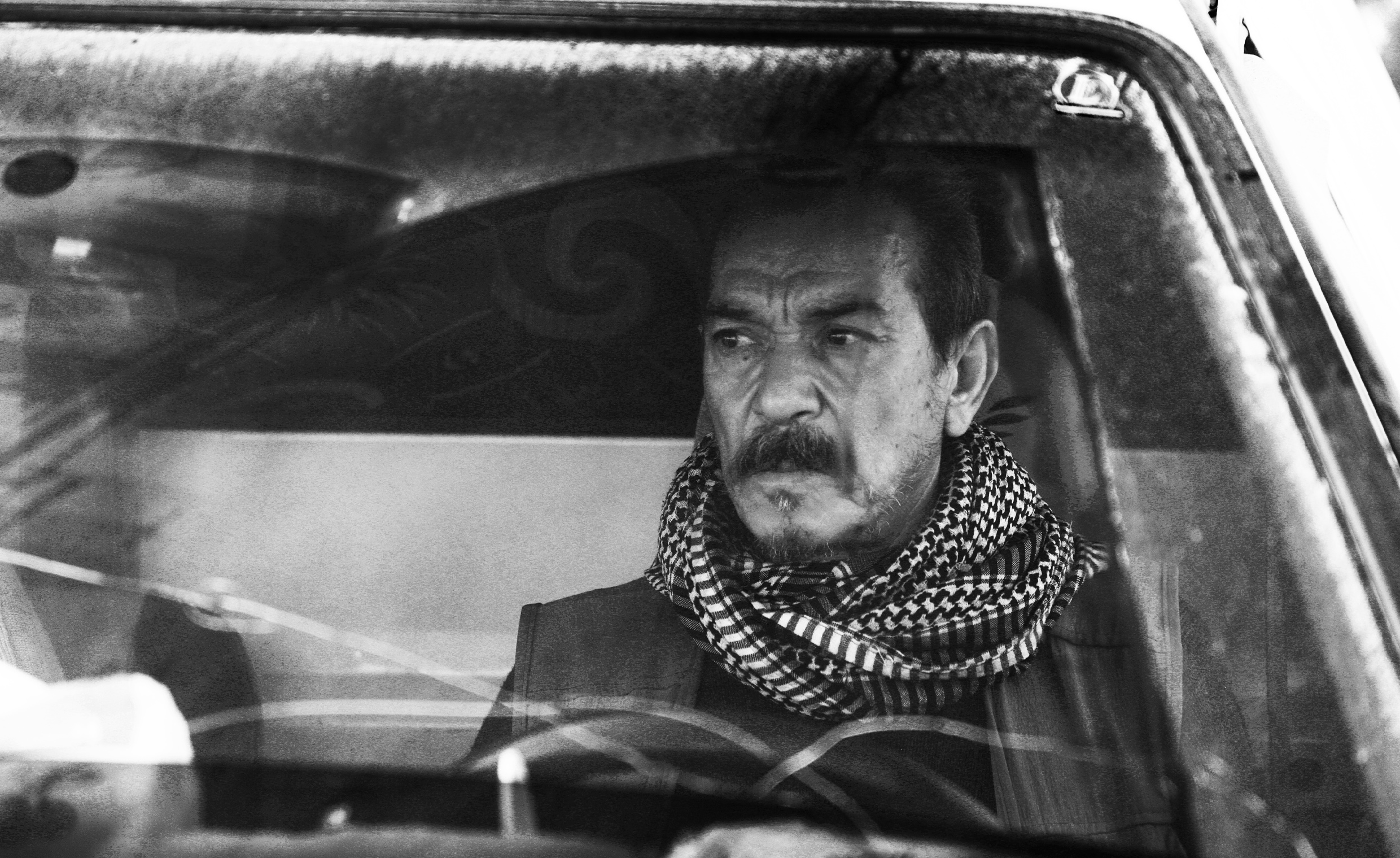

Last days in Aleppo, people again are fearing death and experiencing displacement, amid the battle between the Syrian Arab Army and Asayish (the internal security and police force in the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria). The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the transitional government signed an agreement on April 1, 2025, regarding the predominantly Kurdish neighborhoods in Aleppo, whereby SDF fighters would withdraw and the Kurdish internal security forces, the Asayish, would take over the administration of these neighborhoods. However, clashes broke out between the two sides in the following months. A few days ago, the transitional government forces launched an offensive aimed at taking control of these neighborhoods by force, using various types of weapons and calling on civilians to evacuate.

In the morning, I was staring at the window to the left of my bed. I am visiting Aleppo for the holidays. My neighborhood is the New Syriac, next to Achrafiyye. I have been living in Damascus since 2016, and I come to Aleppo every two or three months. For four consecutive years in the past, I was waiting for death to hit me from the window to my left. Waiting is an understatement, I was anticipating, I was certain that death will hit from there. For over a thousand consecutive nights, I went to sleep, knowing that I will wake up to death taking me from the left.

As I stared at the window, I started hearing clashes, it must be my vivid memory - I thought - but as the clashes got louder and closer, I knew this was happening again.

When the shelling starts and the bullets hit the walls from outside, the tanks are bombing, and the drones are shooting, you are no longer a person. You have no personality and no special traits. You are no longer a human. You are a giant ball of meat avoiding death.

I hid in the bathroom with my mother; we were shaking, unsure if it was the cold of January or the fear. I could hear the neighbors’ children crying, the women screaming, and the men shouting. All the neighbors hide in the bathrooms, and we hear each other’s noises through the small square window connecting the building from the inside.

12 hours passed, then the clashes stopped. We went to sleep, frozen and numb. How is it possible that people outside Aleppo are going about their days as usual? The earth stopped turning here, the air is scarce, and the blood is frozen in our veins. The internet is slow, but now and then, I receive a message from panicking friends from Aleppo, and startled friends watching the news from outside of Aleppo. Fear connects us; it creates a bond no one else would understand, not knowing if you would still be alive in the next minute is a different kind of bond. Each phone call is goodbye, and each word could be the last.

The yellow circles the author's building, near Achrafiyyeh neighborhood.

The second day, we had to evacuate: we had less than an hour, living so close to the areas of combat and receiving bombs and bullets from both sides by mistake. It was a request from the government to empty our building. I packed all the useless things, I couldn’t think. Once I left the house, I thought that I should have taken something that means to me, something from my childhood perhaps. But there was no time to return, and no way to make a decision on what to take and what to leave behind.

We had to walk for 15 minutes, my mother and I, with two large bags and my broken foot, to reach the humanitarian corridor secured for the civilians to exit. I did not recognize the street, my home street. Thousands of people were leaving, crowded, crying, their faces had the same terror I have in my body. We were all one, sharing one massive feeling enveloping all of us together. People were trying to enter to evacuate their young children who were home alone, or their elderly parents. They were not allowed to enter.

Wounded people forced silence when they passed by, we all looked in terror, seeing what we fear the most inflicted on others. The little boy of not more than two years old, had his foot amputated from the ankle. His father wrapped the amputation point in white gauze. He must have had a doctor or a pharmacist help: the kid was asleep, probably sedated. Ambulances were not allowed to enter last night.

We left, but some did not. We survived, but many did not, we have a place to stay, but others don’t. To leave them behind, those who for a long 15 minutes were with you, means leaving a piece of your soul, leaving it with their eyes and pain, them and only them will ever understand how you feel.