Voices come and go, as men and women queue outside the Ibn a-Nafees Hospital in Jisr al-Abyad, Damascus.

“What scares me the most is to die and leave this child alone in this world, without a society to embrace him,” one voice says.

Another turns around: “When I first saw the doctor, I paid 10,000 Syrian pounds [around $20] for the examination, and the prescription cost about 60,000 Syrian pounds [around $100]. I borrowed from my neighbors to buy medicine, which didn't help my son’s condition whatsoever.”

One patient isn’t sure what's worse, "this painstaking wait…or the struggle to even get an appointment in the first place.”

Another remembers the hardships involved with getting to the doctors in their home city. “We would walk long distances from Deir e-Zor, and sleep in public parks until the doctor’s office opened. We would often wait until the next day until we could return to Deir e-Zor. We are used to making these long trips to see a doctor or go to a hospital.”

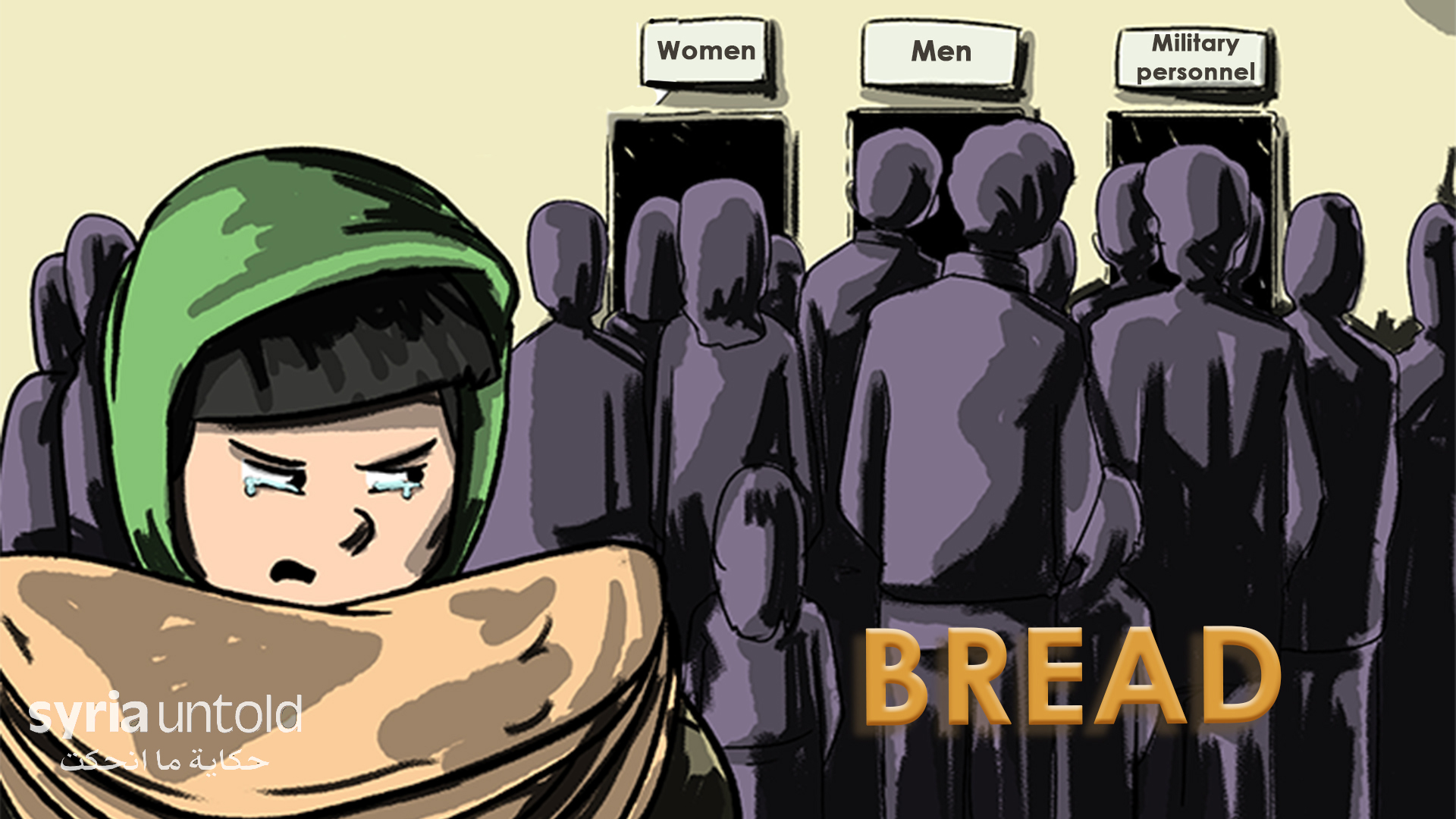

These are just some of the men and women queueing to see a neurologist at the Ibn a-Nafees Hospital. Their complaints attest to the fact that an illness can often be just the beginning—one must also take into account the conditions and pressures parents must live with as a result of their child's illness: the higher cost of living, the lack of doctors in the Syrian capital these days, or the rising costs of medicines.

A day’s bus ride for one 20-minute appointment

Hanan sits with her seven-year-old son, in the waiting room along with dozens of other parents and young patients. She is waiting for her turn to see the doctor.

Many people haven't been able to make it actually inside the waiting room, and so are sitting on the floor on the street outside, at the entrance of the building.

Hanan‘s son suffers from cerebral palsy, causing him difficulties with mobility and delayed mental development. The child’s mental age is no more than a few months, and he is completely dissociated from his surroundings. Hanan has dressed him in a bib to catch the saliva flowing from his perpetually open mouth, due to the slackness of his jaw muscles.

Hanan made her way here with her son via microbus, arriving with several other women and their children who—like Hanan's son—suffer from different types of neurological disorder and disabilities. All of these families were previously displaced from districts such as Daraya and Basateen a-Razi to the Rural Damascus town of Qatana.

Because of the hardships on the road, the mothers coordinate with each other about the doctor’s appointments, and agree with a microbus driver to bring them to Damascus and wait for them to finish, which may take the whole day. They usually return to Qatana late in the day.

The doctor’s examination only takes 15 to 20 minutes, but the wait until leading up to it may take six hours. There are no sanitation facilities except nearby public toilets, which are not clean or hygienic, let alone accessible for children with special needs.

After a long wait, the mothers enter the examination room, where they are met by a hurried physician. They then leave with empty pockets and prescriptions for neurological drugs, some of which are missing from the market.

Exceptional circumstances

Hanan is a widow who lost her husband during the “events,” as she describes them, not specifying who was responsible for his death. She has three other children, all of them in good health. Her son was born in poor conditions, after the family were displaced from Daraya while Hanan was still pregnant, meaning the pregnancy was marred with extreme stress and trauma. Her son was born at the government obstetric hospital in 2012 and, because of what she called “medical negligence,” he suffered neonatal hypoxia which in turn left him with brain damage.

“The birth was a difficult one, and several births were taking place in the delivery room at the same time," says Hanan. “No one paid any attention to my screams and pain. When my son was born, he did not scream like the other babies in the room, and that was when I knew there was a problem.”

"We had lost everything, and I could not give birth in a private hospital. I always think that my son would have been born healthy in other circumstances, but this is our lot in life.”

Hanan sighs and strokes the hair of her son, who is staring into space.

In the clinic, there is also a one-year-old girl who was infected with meningitis in the hospital where she was born, which caused her irreversible neurological damage.

At the entrance to the building, a family from Deir e-Zor sit with their paralyzed daughter. The four-year-old also suffers from spastic cerebral palsy, which caused her paraplegia and frequent convulsions.

The girl’s father, speaking to Syria Untold, says: “Cerebral palsy is widespread among many families from Deir e-Zor—inbreeding is one of the main causes. In my extended family alone, there are five such cases, and I have never heard of a center in Deir e-Zor, Raqqa or Hasakeh to treat such conditions.”

“Patients in these cities come to big cities like Aleppo or Damascus for treatment—not only for cerebral palsy, but also for surgical procedures and cancer treatment.”

Another woman has a 10-year-old son who suffers from severe autism, and who was sent into an angry crying tantrum by the overcrowded waiting room. She gives him her hand to chew on, so he can vent some of his tension.

“I tried to go to another famous doctor in Damascus, but getting an appointment proved impossible,” she says. "There is only one phone number, which is activated for half an hour on the first day of every month. I repeatedly tried to call but the number of callers made it impossible.”

Doctors under strain

Dr. Mohammed Khaled, who asked that his real name be withheld for security reasons, works as a pediatrician in Damascus. Every day, he encounters one or two cases requiring intervention and diagnosis by a paediatric neurologist.

“In fact, there is only one doctor with this specialism in Damascus, and perhaps in all of Syria. There are some neurologists who will see children, but they are not enough.”

According to Dr. Khaled, cases of cerebral palsy are on the up.

“In recent years, I have noticed a significant increase in the number of children specifically with cerebral palsy. I come across these cases every day, whereas in the past I'd see maybe one or two. cases a week.”

He suggests that the difficult conditions that many of these children have been born into—in war, under siege or during displacement—contribute to the higher incidence rate.

“Malnutrition, psychological conditions and trauma during pregnancy, as well as poor birth conditions—all of these factors have exacerbated the incidence rate.”

The Ibn Al-Nafees Governmental Hospital in Damascus, which specializes in the treatment of children with motor disabilities, runs a free physiotherapy clinic. When Syria Untold visited the hospital recently, the hall was littered with mattresses and beds filled with parents, physiotherapists and children. The place had a mild temperature and was full of toys and motor devices, and it was relatively clean. However, there was overcrowding.

Yasmine is three years’ old, but her size and mental development does not exceed six months.

“I was trapped with my family in Douma when I was pregnant with Yasmine," she remembers. “I was very malnourished and stressed, and there was nowhere to go."

“Yasmine was born in these conditions, and we stayed in Douma for two years after that. When the army took control of the area, I left with my family to a shelter in a suburb of Damascus, and we showed Yasmine to a doctor because we noticed that her development was delayed compared to her peers. He requested an MRI, and it turned out that she had atrophy and brain damage."

Yasmine's mother explains that the family is now "committed" to physiotherapy sessions, although she adds that "they are too short, and the therapists are overwhelmed by the number of patients here."

"At the same time, we have seen a slight improvement in Yasmine’s condition after a year of physiotherapy.”

Some hope?

Salah’s parents look on as their son cries in protest as the physiotherapist stretches the boy's limbs.

“There isn’t a real supportive environment for families whose children suffer from cerebral palsy, autism or any kind of special needs,” Salah’s father, a public sector employee, tells Syria Untold. “There are therapists doing what’s needed, but there are so few of them. Some of them are either not skilled enough, or they don't have much experience."

Salah’s mother, meanwhile, voices fears about the future.

“It is most frightening for me to die and leave this child alone in this world. There is no society to embrace him, no safe environment that will see to his improvement," she sighs."This society does not have mercy for the weak; it does not protect them."

“Even walking on the street is a challenge for them.”

Salah’s parents are preparing to enlist their four-year-old son in an intellectual development center, to address his delayed cognition and communication. After weighing several options, the parents opted to admit their son in a center with a monthly premium of 30,000 Syrian pounds (around $50). Salah’s father earns a salary of about 80,000 Syrian pounds (around $140). In the afternoon, he works for several hours as a taxi driver to make another 60,000 pounds. Meanwhile, Salah’s mother dedicates herself to caring full-time for their only child.

The number of Syrian children with neurological disorders has grown significantly especially in recent years, which requires immense resources, societal awareness and a supportive environment, all of which are almost non-existent either for children with special needs or their parents in today’s Syria.

And yet, there are moments of hope.

Also at the center is a 16-year-old boy who walks with difficulty and almost loses his balance at every step—but he walks, nonetheless. He visits the center weekly and makes use of sports therapy to improve his balance and mobility.

The boy's 40-year-old father looks at his son with something like relief. Cases such as these give some hope to the parents in the center.

Sometimes there may be room for improvement—even after the long and stressful journey that has brought these families here.