The question of censorship over the artistic product is one that preoccupies us. In general, the question leads us to think about censorship imposed by political authorities and oppressive regimes that have always done their best to ensure that artistic products that “trouble" their high thrones never see the light of day. The methods for political censorship over artistic and cultural products have varied. Some regimes devised tools to undermine this accusation against them, while on the other hand, many artists have managed to find their way around the censor and still broadcast their voices and their messages.

The Syrian revolution first began in March 2011, a response to the popular uprisings that the Arab region was already witnessing against oppressive dictatorships. Those revolutions, from the moment they started until now, nine years later, have impacted many aspects of life—one of them being cultural and artistic production. Breaking down the barriers of fear has also echoed in various directions, including the matter of censorship and Syrian cinematic production.

Today, after all those years and the things our countries have experienced, as well as the waves of forced displacements all over the world, is it possible for us to approach the issue of censorship as we have done before? Is the question of censorship of Syrian films and directors valid? And if so, in what forms does censorship present and impose itself on the cinematic producer and their product?

‘Ethically abiding censorship’

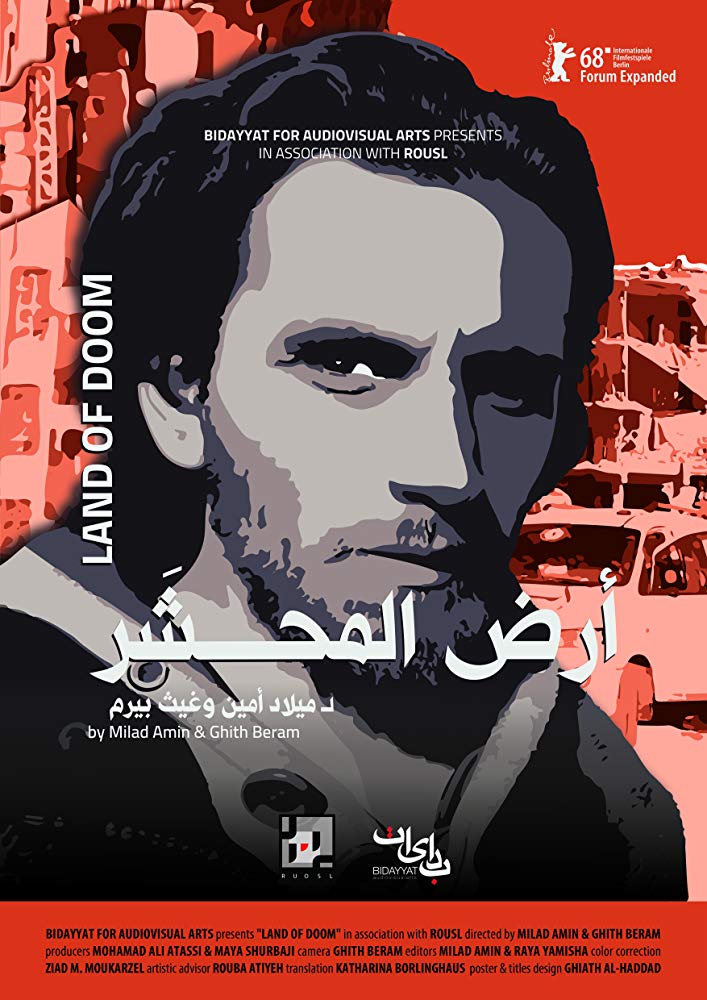

Milad Amin is the Syrian director of the 2018 film "Land of Doom” (Ard al-Mahshar) and lives in Berlin.

He tells SyriaUntold that it was the Syrian revolution that first got him into filmmaking in the first place, so he feels that all he makes belongs to the revolution in one way or the other, or serves it.

Speaking of censorship, he says: “There is always censorship, more profoundly there is an internal ethical censorship. There is a censorship we imposed on others, for example when a director goes to Zabadani to shoot there, or fighting over whether or not a director can film the faces of children. This is all censorship."

"There is a form of censorship related to the privacy of the dead, the privacy of Syrian blood, and the questions of how ethical it is to film blood and maimed faces and corpses. All these questions are up for debate, although I have not personally reached a conclusive position to answer them. I mean, is there a sanctity of the image of a bloodied child, when I have no information about them or their parents? I have no answer, but I try to avoid the questions—and avoidance is itself a form of censorship.”

Amin also discusses a form of social censorship. For example, he says, “to speak of a tree while people are dying.”

“I have not experienced such censorship during my own work, but I sense it, and we practice it upon others [when we say]: 'Are you seriously doing this while people are dying?' This is also connected to the censorship linked to our identity as Syrians, and not just filmmakers. It manifests itself in social pressures.”

Discussing independent productions, Amin says: "I don't know if such a thing exists. Even independent films are not so, because they abide by funding [requirements] and its internal censorship. My experience with Bidayyat or the Syrian Mobile Film Festival, in seeking their support, was because we matched up in our political identities. But these are alliances, they are not independence.”

‘Those that left Syria went out in order to speak'

“What censorship?” asks Syrian producer and filmmaker Guevara Namer, who also lives in Berlin.

"As a concept linked to the state or the statist form that is called Syria? Before the revolution, there was 100-percent censorship. Anyone that had something to say had to die or leave Syria in order to say it. Censorship was absolute."

Before the revolution, censorship would have devoured anyone who carried a camera before they’d even thought what it was they wanted to say.

"Those that left Syria left behind the concept of classical, religious or social censorship, and were put at the mercy of production circumstances. The conditions and limitations in production are not censorship. In a sense, they represent funding resources that come with their limitations.”

Namer does not consider conditions set by funding bodies to be a form of censorship on the cinematic product. She finds more clarity in global production, explained how: “You find a funder that supports a particular type of film, and another that supports another type. We are not limited to one production body that enforces censorship limitations on us. I am free to work with legal institutions or with TV. But censorship in its traditional sense—the one we were used to in Syria—has changed in a 180-degree direction.”

“There is nothing that is allowed or not allowed today. Before the revolution, censorship would have devoured anyone who carried a camera before they’d even thought what it was they wanted to say. Alternatively, they would've left Syria in order to say it. Because when we speak of Syrian censorship on films, we cannot overlook the regime, the clear line, that whoever stayed inside [Syria] had to shut up or die, while those who left went out in order to speak.”

What the revolutions gave me was freedom. I won't give that up: the freedom of how to write, make films or express ideas.

‘The biggest challenge is to maintain my narrative and not oversimplify'

Beirut-based Syrian director Orwa Al Mokdad discusses his experience with censorship and filmmaking through his films including “Being Good So Far" (Ba’dna Taybeen, 2013) by Bidayyat and the 2016 film “300 Miles.”

“We can't say that censorship still exists in the post-revolution context. We now have the authority of funding entities that control to a great extent how an artistic product is made—whether European producers exporting the narrative in a limited context, or local organisations also linked to foreign funding. Sadly, they also abide by market conditions and agendas imposed by supporting bodies."

"The hardest challenge as an independent filmmaker is in the options I face related to the content of what I want to say. I mean, I can go to funding bodies and work on a simple story that addresses the emotions of a European audience, or simplifies the story or generalise it, deals with what is happening by converting the tragedy into a personal story… but then it will be hard to maintain my vision and need to not simplify the narrative. What happened in Syria isn’t simple. So there is always a conflict with the funding bodies and the festivals."

Mokdad also sees that films made by directors making similar choices are not highlighted.

“Not in the personal sense, but in the narrative sense—in addition to abusing stories of blood and corpses to a very large extent. This is not at all useful.”

"In my films, I made the choice to speak about the fighters. The crisis is always that the funding institutions don’t want that, they want to focus on general human stories. This is an exhausting challenge, in terms of finding the funding but also in terms of reaching out to people with this narrative."

Mokdad discusses what he calls social censorship.

"I don't think a social censorship has been formed thus far. It is more about a kind of sharp social discussion about the social product. And the reason for that is related to the nature of the social and political conflict that took place in Syria.”

‘Production conditions are found everywhere in the world'

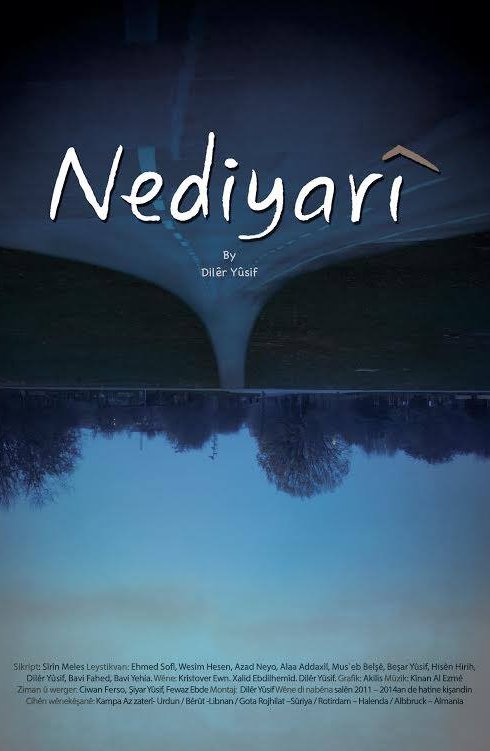

Berlin-based Syrian director Dlair Yousef, behind films such as Habel Ghasil (2016) and “Exile” (Nediyari, 2014), no longer feels he is subject to censorship and does not accept any political or social censorship, either.

“What the revolutions gave me was freedom. I won't give that up: the freedom of how to write, make films or express ideas.”

"I don't think there's anything that can tie me down—here I'm speaking from a very personal perspective—notwithstanding production conditions (that is to say, how a certain film or idea is produced). This is not linked to Syria or the relation specifically, or to any time and place. It is present everywhere.”

‘Producers are looking for the cinema of words, not cinematic language'

Director Soudane Kaadan lives in Beirut. Some of her previous works include Aziza (2019) as well as her latest, the 2018 film “The Day I Lost My Shadow" (Youm Ada’t Thilli), which was awarded the “Lion of the Future” award for best debut film at the Venice Film Festival.

“When the revolution started, the censor disappeared," she says. “This created a sense of loss, with people asking themselves: ‘So now we can speak directly, just like that? We're not used to it!’”

"So the first films to come out were very direct, a kind of necessary screaming. The films that came out in that first phase after the revolution were documentaries, telling their narrative directly. There was a pleasure in wording things directly."

“But then we discovered that cinema is not like that. It is not a speech you present to an audience. That is the role of the activist, but not of the cinema. It cannot be in one language, either."

Kaadan views this as a problem linked to the funding institutions that wanted things put directly, giving little space to those with different narrative styles.

“Some of us, myself included, wanted to make fiction films, and were met with questions like: ‘Why not make documentaries?'"

One of the challenges that Kaadan faced was finding funding for her feature-length film, “The Day I Lost My Shadow.” The process took a long time, she says.

“There's this preference for documentaries over fiction films, because the documentary satisfies the curiosity of the voyeur, as they say, the viewer needs to know the truth of what is happening in the war and documentaries cater to this need. So there's a global interest in documentaries. This curiosity doesn't mean that there have been any solutions presented for the Syrian issue, though."

“There is no international interest in creating a Syrian cinema, or funding it, if you want to make or say something different without practising self-censorship. It’s a long process. Of course, there were documentaries that leaned towards indirect speech—either creative or analytical ones—that did not want to spell out their narrative. But those films encounter funding difficulties. True, they manage in the end, but they did not get the attention they deserve, or the attention received by films of words rather than language."

“Perhaps this isn't all censorship, rather that funding encourages one thing at the expense of another. So international funding can decide what it wants to see, or what it wants to hear, about us."

When I contacted the directors, I sounded out the idea of the piece, asking a general question on the relationship between censorship and the cinematic product. I meant for the question to be open, to give the directors the space to take it in whichever direction they wanted to go, leading me towards a different set of questions each time. And so I got unique answers from each one of them on what censorship is as a concept.

Perhaps when we are “liberated" from its (relatively) political context, this opens up fresh questions and interpretations—or is that what happened when the walls of fear were crumbled by the uprisings?