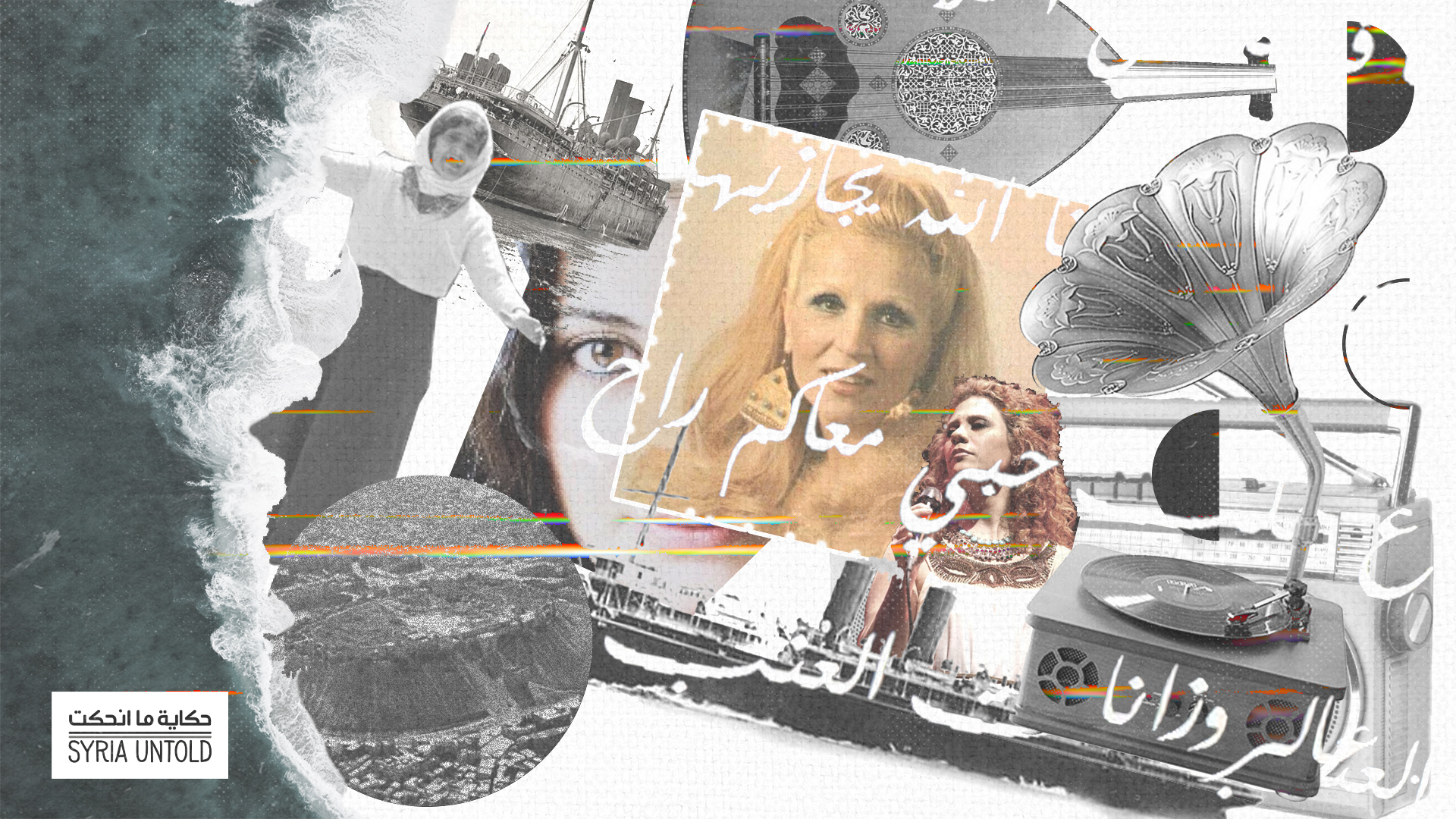

This article is part of SyriaInFocus, a series on Syrian photography funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, with guest editor Sima Diab.

Read this article in Arabic here.

“Arrest the Syrians who raised the flag above the Arc de Triomphe.”

“Yes, sir, but what do these Syrians look like?”

Homs, summer of 2006:

I am lying on the couch in my room. I have just woken up, but I can’t get up. I look at the floor, and I stare at dozens of photos on top of a pile of newspapers that still carry some traces of water after another long night of work stretching until the morning, when I printed them. Since I could not leave a white frame around the photos upon printing them, I did not want to hang them on the rope using clips, to avoid leaving a trace on them.

I just placed them above several piles of newspapers on the floor right after washing them with water. That was the first thing I did almost daily when I woke up—I collected the photos because I was afraid I would crush them with my feet by mistake. But, today, I feel exhausted. I have been feeling this way for two months, and I haven't been able to solve the problem. I no longer can or even want to do the most fun part of taking photos, which is printing them.

Mulling over what happened and tripping between wakefulness and sleep, my eyes would catch a glimpse of the photos on the floor, and my dreams would manipulate them; changing their form within minutes, before I awaken to realize that the photos had returned to their initial form.

Only two months ago, I left the job I had always dreamt of in photojournalism. What’s worse, I could not keep it up for more than six months. The idea frightened me. I had changed the course of my life in the past, after tough and bitter years during which I was in the military service. The idea of reshuffling my life again was out of the question.

Nothing major happened really. I just felt I could not take photos anymore. I turned off my mobile phone and locked myself up in my rented house in Damascus for three successive days, during which the events that I should have been shooting burdened my conscience. I felt like one of the angels who escaped a holy and divine duty to record the sins of humans.

After I grew certain that my conscience, which would not budge the first three days, still wouldn’t on the fourth day, I decided to quit my job and return to Homs.

To avoid additional problems, I decided to withhold the reason behind quitting from my family. I did not want to tell them that I had lost the desire to press the button on the camera, and I just said, “I was fired.” That was quite common in the emerging private sector in Syria at the time. I was willing to face my family’s acceptance of my failure rather than my weakness towards the camera button, which any person could easily press then and now.

At first, I thought I was overwhelmed by the numerous demands of journalists who did not hide their happiness with my presence among them. They would ask me to take photos of anything their eyes spotted; anything that would constitute material for an article to be published in the magazine. Such tiredness would normally fade after a good night’s sleep. But it lingered, and was joined by a taste of bitterness in my mouth when I would wake up in the morning, even after three days of leave that I forced myself to take. Bit by bit, I lost my desire to take photos to the extent that I hated carrying the camera. I was losing myself in a way that was impossible to explain. The feeling scared me, and the only solution I found was to quit my job and retreat to my room in Homs, where I would hide until the truth was exposed.

Reigniting the old spirit of photography was my only way to search for a solution to the problem. I returned to the old video camera, freelance photography and the traditional development and printing of photos. I thought that my work with the digital camera might have had a negative effect. The first time I captured 1,000 photos ready for publishing a moment after taking them, I had a negative sentiment that resembled throwing a stick of dynamite into a fish pond. Only I was that fish pond. I felt that experience ruined something that I had to dig deeper to unveil.

I did not have many places to explore that would make my search draining and difficult.

I often waited for when the streets emptied and there were no passers-by, when the strong wind blew, to enjoy long walks or look down onto my garden from the second floor balcony. As for the roof, I had to sleep there in summer despite my mother’s objections. Still, here I am, two months after a daily journey of deep exploration of my inner self that seemed hollow, and I find myself unable to get up yet again. My mind and dreams clashed over the form of the last photo, as though each of them wanted to see something different.

That evening, while I leaf through an old notebook in an attempt to double check some rules for using colored filters while taking photos in black and white, I read in the corner of a page the following question: “Where is the most beautiful photo in the world?”

Damascus, summer of 1997:

I had to stay in Damascus that summer to pursue my Japanese language courses and complete my internship in a touristic services office. Unlike the great pleasure I found in studying history, archaeology and languages, the training at the tourism office was laborious and complicated. Compared to it, the Japanese kanji symbols were a walk in the park.

The peak of complication was when the office director told me once, “You have to be sly.” It was then that I learned the difference between language and speech. One can master a language by studying it, but the only way to understand speech is through life experiences. This understanding made my task even harder. It was a very tough summer, to the extent that my visits to the family house in Homs became a spiritual need rather than routine visits.

That summer, I bought my first roll of black and white film, after I discovered my love for photography through my colleagues' cameras on our weekly visits to archaeological sites. I was bored with them taking photos the way they wanted. I decided to have my own roll of film and capture whatever I wanted. My only reference at that time, when I had no internet or computer, was a large bag of old random photos in the closet of my mother’s bedroom. I held on to what was left of my father’s belongings after his death, in early 1987.

Although I had gone through it dozens of times in the past 10 years, each time something new would surprise me.

I did not believe in the bag’s magic powers, except during that summer when I found a strip of negatives in a metal box. After asking my older brother about it, I discovered it was the last roll of film in my father’s camera.

Evading the complications of the present and its obscure characters and running back to the simple and clear past, I found my return from the past rigged with far more complications and a vaguer picture than the images of the capital’s characters. After I developed the negatives, which were mostly damaged because they had not been properly preserved for a long time, I found in the negatives the features of one photo that I asked the printing technician at the lab to print. However, he turned my request down, claiming that it was too damaged for the automatic printer to properly process. It was transparent to the extent that the three people in the photo looked like ghosts with their facial features blurred.

With complicity, I quickly surrendered to the words of the printing technician and left. A hidden feeling of happiness prompted me not to go to any other lab and try again, as if I was happy the photo was blurred and I could continue imagining it as I wanted. I could keep that link with the past that sent me the picture. I wrapped the negatives inside their original metal box and hung the box with the house keychain so that the photos would always be in my pocket. In the future, would touch them with the fingers of my right hand each time I missed talking to my father, just like I did the last time I was returning home with him from a carpentry workshop in the evening as he held my right hand all the way.

Homs, winter of 2003:

“Where is the most beautiful photo in the world?” the photography teacher asked me.

“In my pocket since six years ago,” I thought.

The only reason I did not say that answer out loud was that I wanted to keep the photo to myself. The teacher said: “It is in your mind and should remain there. The moment you let it out, you will be dead!” He meant artistic death.

Perhaps it was a good thing that I remained silent and did not hastily blurt out that silly answer. I did not want to seem dead to my teacher and friends that quickly. It was also good that the photo was somehow in my mind, and I always imagined it. But after I heard the teacher’s answer, I was afraid of printing it because I was not sure that another image would come to mind instead. That picture was the only boat that carried me to the past and reconnected me, sensually rather than metaphorically, with what was taken away from me. The picture from my father might have been all I wanted, but if I printed it, it would take a final form. The boat would then vanish from my mind, and I would lose my only means of travel to the past once again.

The teacher’s answer was not written on the page of a notebook the moment I read the question that summer in 2006 in Homs. Still, I remembered the whole story. The question was chiseled in my memory. I now think that I might have really been artistically dead when I worked in Damascus without realizing it. That pain only stemmed from my refusal to leave reality! I then wondered about the use of keeping that photo, which had an unknown gist and identity, so long as it did not save me anymore. I decided to print it that night.

The available technology did not facilitate my task of printing that ghostly photo. Even when I closed the projector lens all the way to the end and set the print time to a few seconds, I got a totally black image. I had to hold a black paper to block the light rays from the photosensitive printing paper and to move it back and forth as quickly as possible so that it would receive the right amount of light, just as the eye sees something in a flash. The result was worth the death of the most beautiful picture in the world—I could make out my childhood facial features as my father had captured them 20 years ago in that last picture where I stood in front of my older sister, who carried my youngest sister in her arms. However, shockingly and like in a fairytale, I woke up the next day, and on the floor was one picture that crushed 20 years of absence. I felt lighter. Although that image no longer inhabited my imagination, the pain and tiredness greatly diminished.

Searching for the reason, I thought that, although the imagined picture always seems a future one, which makes the photographer a theoretical human, imagination can only be based on past images, events, dreams, people and acquaintances that largely impose on the imagined picture the spirit of the past. The longer it lingers, the more it impedes the photographer from seeing reality. If that is indeed true, then the story of the five men wandering around the village and carrying a big boat over their heads actually applies to me. When a villager asked them why they were carrying the boat wherever they went, although it almost crushed them, they said, “This boat rescued us from death on the other bank of the river. We wouldn’t have survived without it, and we cannot leave it.”

Yet, how can one photo crush me? Perhaps it was not one photo. It was certainly the only physically present image, but maybe there were other ones concealed, lurking somewhere in my imagination. I got greedy. I wanted to be even lighter and perhaps grow a pair of wings! I began chasing the hidden images in my memory. To print them, I only had to summon them to my conscious mind and retrace their features accurately in my mind to stop them from endlessly shaping themselves in my imagination and draining me.

To search for these photos, I revisited all the places where I spent my time in my imagination. My mind was observing. In my head, I walked the empty streets of the city while the strong wind blew, and I saw my brother who was one year older carrying the green ball in his arms while I followed him in my quest for new challenges in faraway neighborhoods, after he had defeated all the kids with his charming maneuvers. That was one of the last times we played ball together before my father’s death.

In my imagination, when I climbed to the roof of the house in summer to sleep, the neighbor’s daughter with her long black hair followed me and stretched her body above mine. She only left me at the gate of the dream. In the early autumn, she left for Beirut, and I no longer heard anything about her. It will be difficult to remember her face from our encounters that only happened in the night. The few times the moon was full would be my only source of light to determine the image accurately. When I went up to the balcony of the second floor in my imagination, I saw myself, from where I was standing, stretching out my hand to the branch of the berry tree to pick the fresh berries and devour them immediately. It was the oldest tree in our garden. It was so huge that it reached the third floor, and its branches extended into three neighbors’ houses.

When its roots nearly extracted the tiles of the garden, my family decided to cut it so that the foundations of the house would not be shaken, as per the advice of a knowledgeable person. How could hundreds of photos in that magic bag not contain one picture of that berry tree?

A few months later, in the autumn of 2006, I was sitting in my room when I suddenly flew up in the air, and my head almost hit the ceiling. Only the silence of my brother and mother who were sitting by my side rescued me, and I calmly returned to my chair. I had just read the news that I won an award in Rome. Paradoxically, the theme tackled the situation of young people. I had indeed grown two wings that would only disappear when I left Syria for good.

At the beginning, the reactions of my mother and brother upset me, but after thinking about it, I realized that they might have not believed me. How could I win a European prize when I was just fired from a local magazine in Damascus? I forgot that I had lied to them. How could I travel to Italy when I didn’t even have five liras to take me anywhere in Homs?

That was the image I drew of myself in the imagination of others to prevent them from seeing my real situation. I won’t blame them, but I won’t explain either.

My return from Rome coincided with a new job opportunity at a local daily newspaper. It was my gateway to reality once again. The daily work was endless. Even on Fridays, I had to shoot the games of the local football league, and my visits to Homs declined gradually. Perhaps I was tired sometimes, but I never felt stressed. I would empty my imagination daily of any image that was stuck but I couldn’t capture, and I would return daily with a larger memory, empty imagination and wide-angled, dreamy eyes resembling my eyes in the old negatives—eyes that could see the future, should it decide to grace this country which knows nothing but the past.

There was no need to hide the two wings because nobody would believe they existed, even if they saw them with their own eyes. For that reason, I would stick some funny images of Assad on the wall behind my office in the newspaper until the future indeed decided to visit us in 2011, when the Syrian revolution broke out.

The pictures of the protesters who took to the streets on March 25, 2011 from the Umayyad Mosque revealed my wings, and I realized that I needed to hide them. When I reached a point when I could no longer fly, I left for Aleppo where the war was raging. Imagination and reality were physically present at the same time, and they had a rare, short-lived harmony. The public revelation of my wings was not dangerous, as everyone there had wings of different shapes and colors. As long as death was limited to the snipers’ bullets, knives and cannonballs, it was fine. We always managed to rise with our wide-angled, dreamy eyes and an imagination ready to embrace the future. But, then, the scope of destruction widened. One Scud missile would destroy a whole neighborhood, and the aircraft raids with their indiscriminate shelling paralyzed my ability to empty my imagination. Although death is a natural part of the future, when it becomes the only sight, the future disappears and life becomes an image of the past. Although my father passed away years ago, thousands of fathers have died here. And, even though one berry tree was cut in my house, all the trees were cut here. Although my childhood ended suddenly, there are no children left here. Bit by bit, my imagination was filled with thousands of images of what life should have been. Naturally, I could not capture all the scenes before their destruction, or perhaps I arrived too late. Those images of life wanted to be rescued and to cross through the boat of my imagination to another place. That feeling was so intense that by the end of 2013, I found myself once again incapable of taking photos and carrying a camera.

Paris, 2014:

Sitting in a cafe and thinking whether I could translate all those images far from their reality or that I might be able to see reality once again one day, I was joined by the Syrian cafe owner. He told me about that policeman who was ordered to arrest Syrians who tried to raise the flag of the revolution above the Arc de Triomphe in Paris during a protest supporting the Syrian revolution. He told me how that policeman did not get an answer from the commanding officer when he asked the officer what these Syrians would look like. At that moment, I thought that the most beautiful picture in the world had formed in that policeman’s imagination, without his knowledge. No matter how much he tried to retrace it in his consciousness, it would resurface in his imagination because we do not have one perception of an image. That picture will be the lifeboat we left behind, which will crush all the policemen of the world with its impact.