This interview is part of SyriaUntold’s ongoing series on the world’s “Little Syrias,” communities of Syrians in the diaspora.

In 1910, a girl was born in rural, vast South Dakota, the daughter of homesteaders who had immigrated from what is now Lebanon, thousands of miles away. She entered an arranged marriage at 14, but later divorced, found her way to New York City, became a Muslim community leader and even forged a long-term friendship with Malcolm X. She later served as a leader in the Arab American community in Detroit. Her name was Aliya Ogdie Hassen.

Ogdie Hassen is among the handful of characters and places profiled in Muslims of the Heartland: How Syrian Immigrants Made a Home in the American Midwest, a book forthcoming in February 2022 by Edward E. Curtis IV. Curtis is a professor of religious studies at Indiana University.

Curtis is himself the descendent of families from Ottoman Syria who emigrated to the US in the 1800s and 1900s. He later learned their stories through his grandmother, he tells SyriaUntold.

Once in the Midwest, thousands of miles from home, these families would have rebuilt their lives from scratch. They became homesteaders, peddlers and community leaders. Unlike other parts of the US where Syrian immigrants found new homes a century ago, those who arrived in Midwest at the time largely came from Muslim families. They continued speaking Arabic and practicing Islam while adopting a newfound “American” identity, however they chose to interpret it.

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

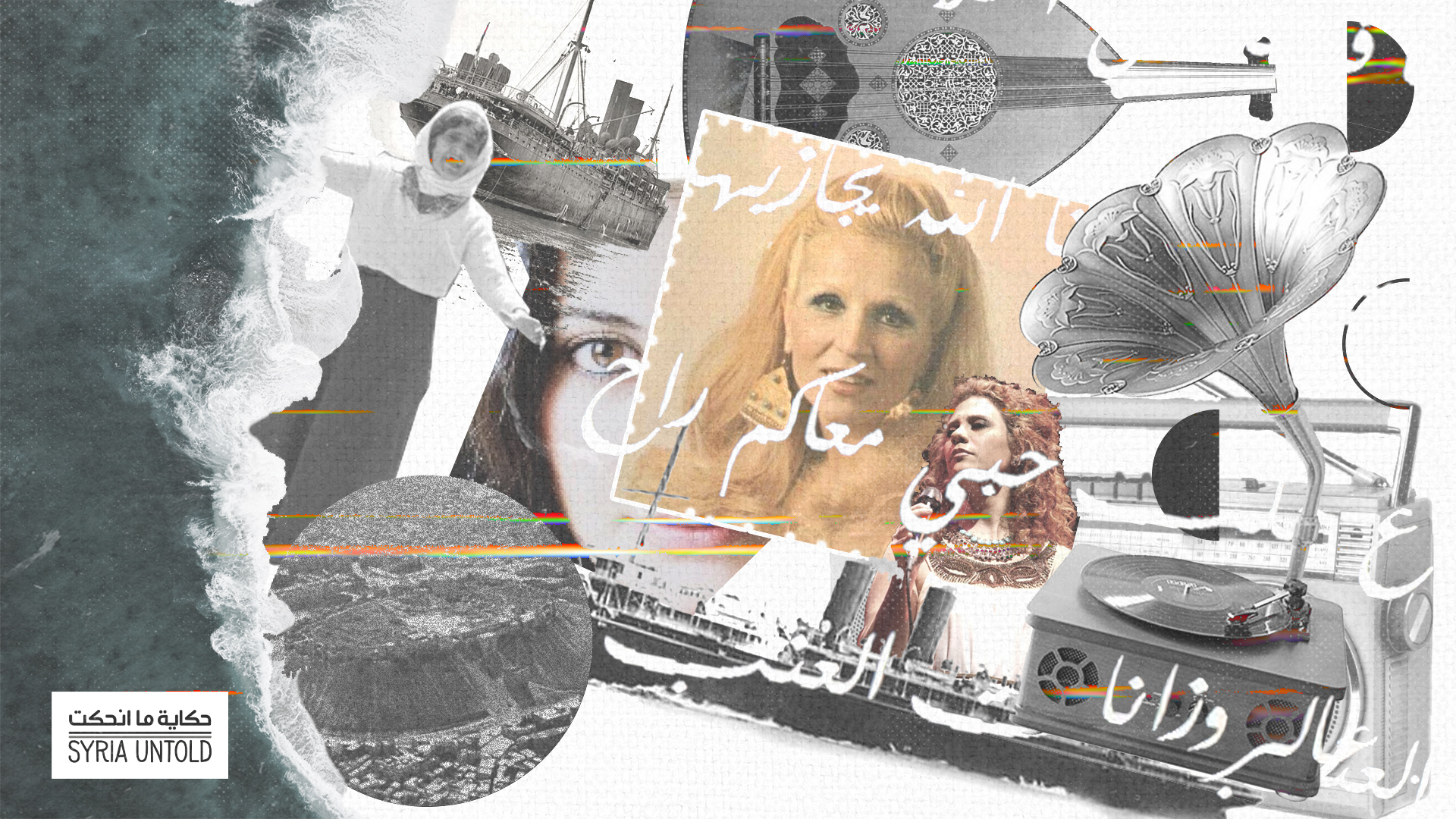

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

And yet, their stories are not widely known today. “Muslims and Arabs have always been people of the heartland,” Curtis argues.

SyriaUntold spoke with Curtis over email. This conversation has been lightly edited for flow.

To set the scene a bit: If you were someone living in a Syrian or Lebanese Muslim community in a Midwestern city around the late 1800s or early 1900s, what would your surroundings have looked like? Would you have had a dedicated community center or mosque?

The Midwest was booming at the time—new railroads, new farmlands, new factories. If you lived in a rural area, you might have roomed in the wood-frame house of a farm owner or built a 10 x 12 tar-paper shack. If you were a peddler, you would sometimes have slept outdoors, in your wagon, or in some person’s barn.

But if you lived in an urban area, you lived in a boarding house or a small, narrow wood-framed house. You probably did not have a community center—the mosques didn’t appear until after World War I. Instead, you met in each other’s homes, in coffee houses, and in open spaces. You spoke Arabic at home and English at work.

You write that the Midwest had the highest percentage of Muslim Syrian immigrants in the US at the turn of the century, as opposed to Christian immigrants, who were the majority everywhere else.

Why was this the case? What drew these families to rural Indiana, Iowa and the rest of the Midwest, rather than, say, New York City, where there were perhaps more job opportunities?

The lure of free land—homesteading—was especially important to Muslim farmers, or those who wanted to become farmers.

[Editor’s note: In 1862, the US government issued the Homestead Act, allowing applicants to receive plots of land for free in return for settling and cultivating it. This was one strategy used by the US to settle "frontier” states where the territory originally belonged to Native American tribes.]

It was possible to be both fully Arab and fully American at the same time.

You argue that the “ethnic-religious identity” of Muslim families from Ottoman Syria became a “pathway to assimilation” in some parts of the Midwest. How did their identity as Muslim Syrians help them to assimilate into American life in the Midwest, and to what degree was this new life actually similar to their previous lives in Ottoman Syria?

Some of them became more religious when they came to the United States. They prayed, sang songs of praise for the Prophet Muhammad, and celebrated Eid together. The United States was and is a religious country. Having a religious identity and a religious community is a pathway to community engagement and community power.

‘Little Syrias’ in a big world

26 July 2021

What did exile change in our narratives?

26 January 2021

In what ways did they embrace, take on, or embody an “American” identity? To an immigrant from Ottoman Syria at the time, what would it have meant to be “American”?

To be American for them was to love both the national and local cultures of which they became a part. They fought and died for their new country in World War I; they participated in elections and organized for workers’ and farmers’ rights. They also loved cars, the movies, and in some cases, American dancing. But they still worked for Syrian and Arab self-determination, taught their kids to be Muslim, and loved to cook and share Levantine food.

You write about American “settler myths” and the ideal of cultivating one’s own land and building a kind of “rugged” life. To what extent would families coming from Ottoman Syria have heard about these myths or been inspired by them to settle down in the Midwest?

For sure, they took on a shared identity as American farmers, and they repeated the same kinds of stories that other farmers did about how hard it was to make a living at it.

My book profiles the lives of farmers in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Iowa. Some of them were farmers back in the Bekaa Valley, some were not. Aliya Ogdie Hassan, who was born to one of these families, liked to talk about her family as pioneers and the challenges they faced—the rattlesnakes especially. In doing so, she was participating in the American tradition of frontier myth-making.

You've mentioned that in many places in the Midwest at the time, you wouldn’t want to have been very public about being Muslim—can you talk more about this dynamic? How did the non-Muslim broader community treat Muslim immigrants from Ottoman Syria? What were relations like between these communities?

Yes, I am sorry if that contradicted what I said earlier about Islam being a pathway to power and assimilation. What I meant was that where you might have been the only Muslim or there may have only been a handful of you, you would have been less likely to share this identity with others, especially non-Arabs. You didn’t have a community to back you up, and many Americans had prejudices against Muslims and others whom they considered to be non-Christian, non-white foreigners.

Did you have a favorite person or place whose story you told in the book?

I loved telling the stories of all the book’s characters. The book begins with the story Aliya Ogdie Hassen, one of the most important Arab American and Muslim American leaders of the 1900s. She was born in rural South Dakota and educated in Sioux Falls public schools. She exemplifies one of the main points of the books: it was possible to be both fully Arab and fully American at the same time. She loved being both. Immigrants and their children are not always torn between the old country and the New World.

Most people don't know that people were moving from Ottoman Syria to the American midwest in the 1800s and early 1900s. How do you hope your book will contribute to popular understandings of Arab America?

For too long we have told a story about America’s heartland that excludes religious and racial minorities. We have whitewashed our own history. It’s time to tell the truth. Muslims and Arabs have always been people of the heartland.