This article is part of a series on Arab photography funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, with guest editor Muzaffar Salman.

When I sat down to write about my experience with photography in Palestine, I was overcome by sadness and fear. I realized that I had never really captured Palestine. In truth, when I was a child, my Palestinian identity was linked to my father.

You see, my father is Palestinian, therefore, I am Palestinian. My father protects me, therefore, he is my homeland. My father spoils me and keeps me safe, therefore, he is my country. That was my understanding of being Palestinian. When asked, “What are you?” I would say, “I am Palestinian.” They would say, “Why?” I would answer, “Because my father is Palestinian.”

Until this day, I hear a lot of children introducing themselves based on their father’s identity. But, when I dig deeper into my father’s identity, I realize I loved him as he loved us. I loved how he would get up in the morning at 5 a.m. to prepare breakfast for us before we went to school and before my mother woke up to go to work.

My father—that warm man who would treat us to kaak,a type of pastry, and falafel—and who would take us to Jerusalem at night to have manakish flatbreads with eggs and zaatar herbs.

That was my father, and that was Palestine for me, or perhaps, that was Palestine for me before the Israeli forces stormed into our house one night and arrested him. He disappeared for two years, and with him, the teapot, the breakfast, the kaak and falafel, my mother’s spirit.

In search of the best picture in the world

22 January 2021

Homage to Aleppo

16 November 2021

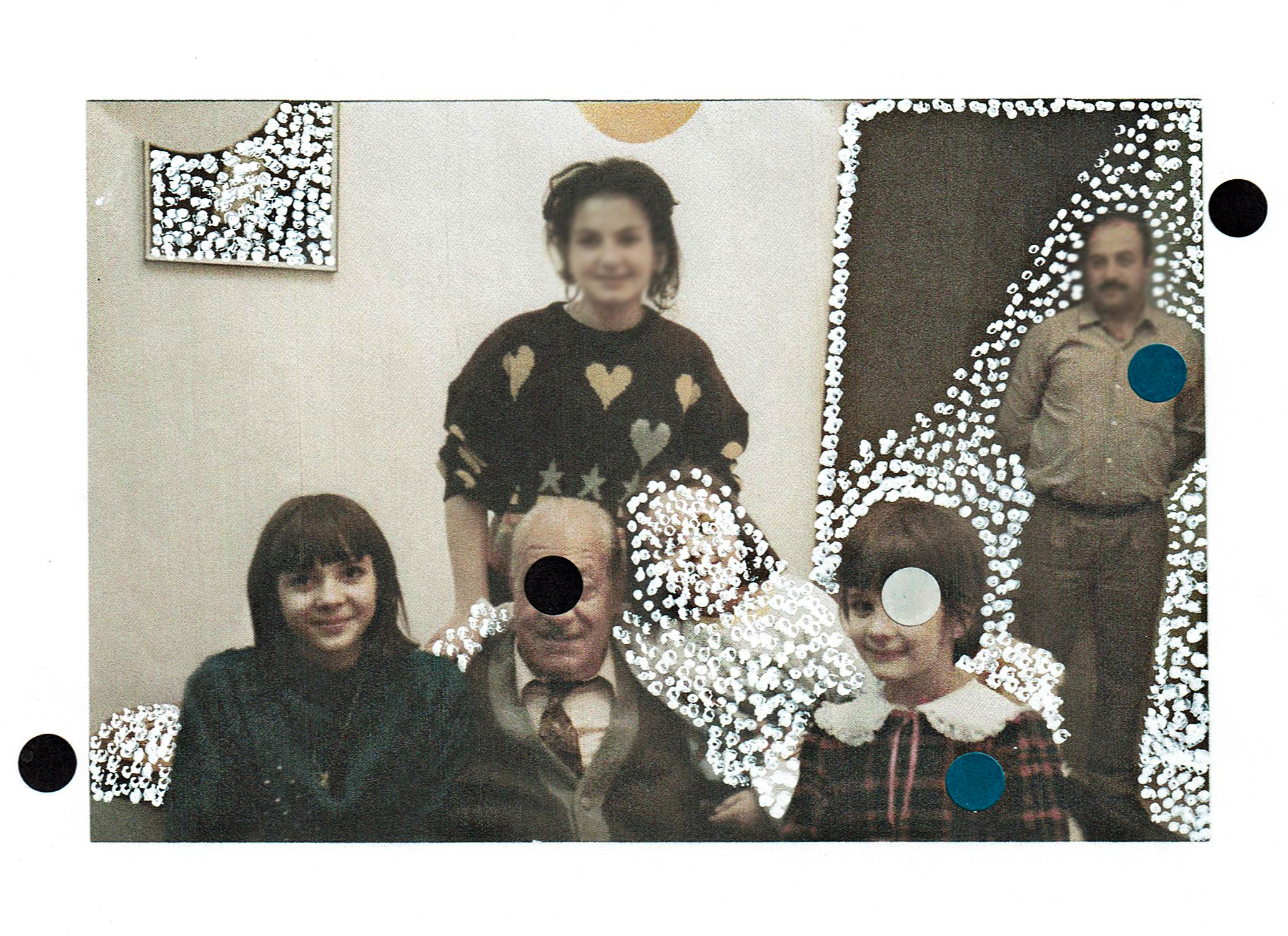

When my father returned, he was thin and had a long beard. I have a photo of him that day, from after he was released. He was playing with my baby cousin who was born when he was in jail, and as I sat on the floor, I looked at him fondly without understanding what it meant that he had returned with this new appearance.

With time, I began to notice his insomnia. He would wake up in the night and spend hours in front of the television. He had a chronic cough, which doctors could not explain. Eventually, he lost the sparkle in his eyes, and his mood was off. We no longer screamed or laughed in front of him. We no longer spoke our mind over lunch or even allowed ourselves to finish our meals. Upon his return from work, a precarious silence would fill the house.

When I was 16, I left the house and Palestine to pursue my studies abroad. Throughout those years, I felt loss and nostalgia for my country despite my repeated visits. I felt the same fear and emptiness that gripped me ever since the Israeli army raided our house. I can no longer sleep without locking my room. I spent several years abroad spiraling in a turmoil of loss and nostalgia. Three years ago, I decided to return to Palestine for good to work as a photojournalist and cover stories and topics that do not receive enough media attention.

Here I am today, looking for a photo or story that I captured here and that reflects my experience with Palestine. Instead, I am incapable of finding any truly representative project. I told myself, “I must ask some questions to guide myself to this photo or project.” But, in vain. I would angrily ask myself again, “What are you??” At that moment, I realized my inability to choose the photo that best describes Palestine for me.

How I wish to take a photo of him, as he walks happily across the streets of Jerusalem.

“What am I? Palestinian? Why? Because my father is Palestinian? Show me your father! I don’t have a picture!!” This is simply how it is. I have not taken a picture of my father since I went into photography! I do not have a picture of my identity. The image that prevails over all others is the missing picture of my father. The picture of my father who would prepare black tea for us each morning, the picture of my father who would collect the crumbs off the table to feed the birds. This is the picture whose features the occupation changed completely, just as it altered Palestine’s geography. The features of our family were no longer the same.

How I wish to capture a photo of him that would reflect a reality we yearn for. How I wish to take a photo of him, as he walks happily across the streets of Jerusalem. Oh, how I wish to photograph him between the trees in that mountain which is no longer ours, but which has become a settlement. How I wish to take a photo of him smiling or laughing—just a true photo of him, not of the man the political situation turned him into.