This article is part of a series on Arab photography funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, with guest editor Muzaffar Salman.

Read this piece in its original Arabic here.

The author would like to acknowledge the management of Tripoli’s Old City, fellow photographer Heba Shalaby, who launched the campaign #SavetheOldCity, and the sculptor Hadia Qana, who has contributed to preserving the Old City. Thank you to each person who contributed one way or another to saving part of our visual history and left us an outlet to escape when the present was too difficult to bear.

I don’t know what it means to hide behind the veil of memories, and I can’t pin down exactly when I picked up this habit. It cannot have been more than a decade since I began feeling the need to cling to images of the past—though they are pale like our streets and our facades, which we mistakenly believe are capable of improving our image.

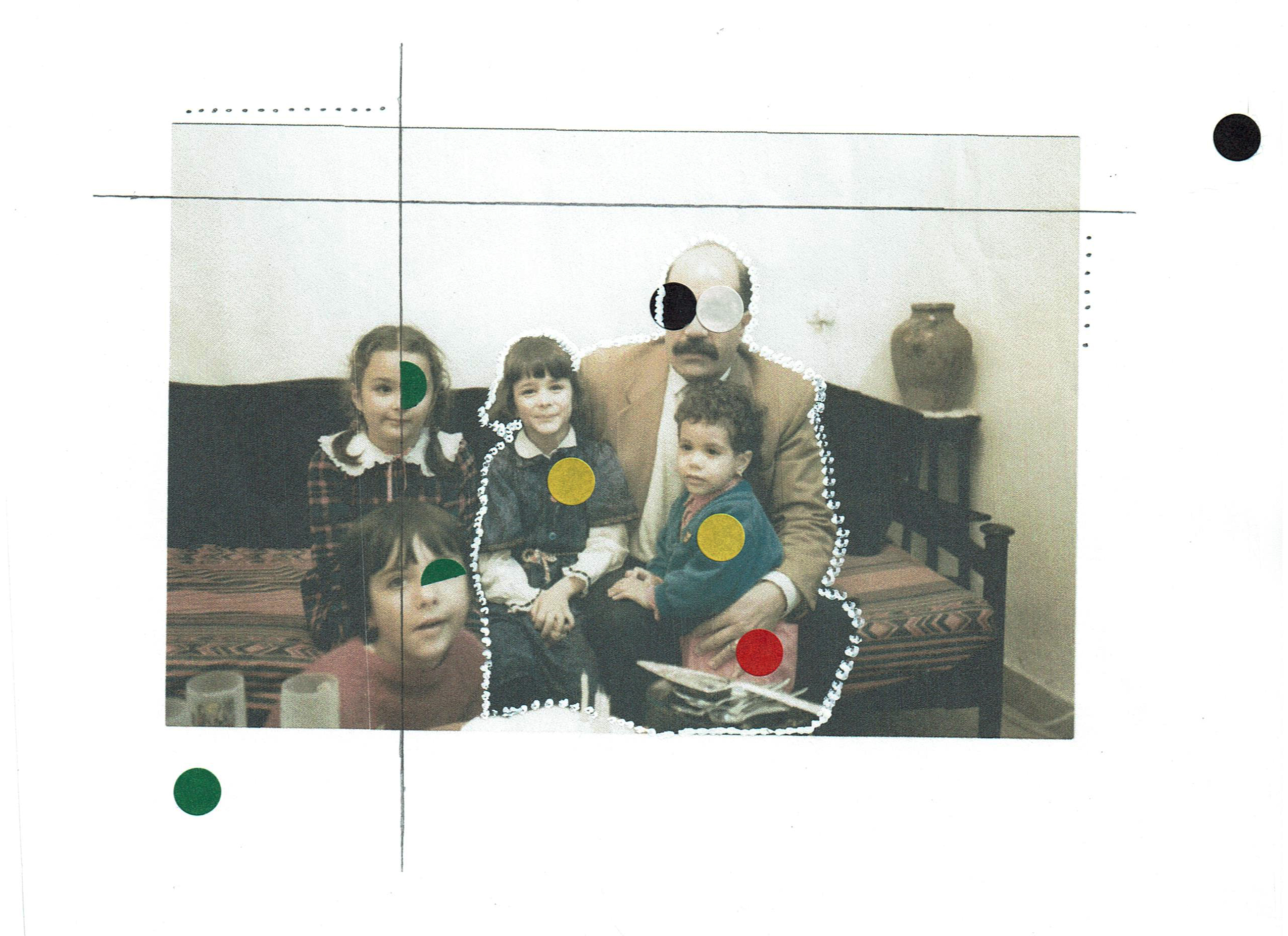

I remember that, around 20 years ago, I embarked on an exhaustive journey to search for the big family house in the Old City of Tripoli. I wanted to look for the properties my father had left behind. I remember he would collect rent from the tenants who would occasionally knock on our door on Omar al-Mukhtar Street.

At the time, I was searching for my father’s legacy for purely financial reasons. I didn’t have any official papers for the property, as they had all been lost for one reason or another. My family was in dire financial straits, and I was like a drowning person grasping for straws. Hence the imagined pictures from my memory and the handful of stories my mother had told me, all dating to more than a decade before I was even born.

Contradictions of the city

During my journey, I heard bits and pieces. Essentially, the big family house had collapsed and disappeared over the years. This is how my bond with the Old City began: fragile, shy and unserious.

Homage to Aleppo

16 November 2021

I trusted what was said regarding the big house, but I had no hope of discovering what had happened to my father's remaining properties. What a contradictory, yet wondrous, memory of this city! While it can tell you its own history down to the smallest detail, it is capable of overlooking or forgetting other closer and clearer events, whether deliberately or not.

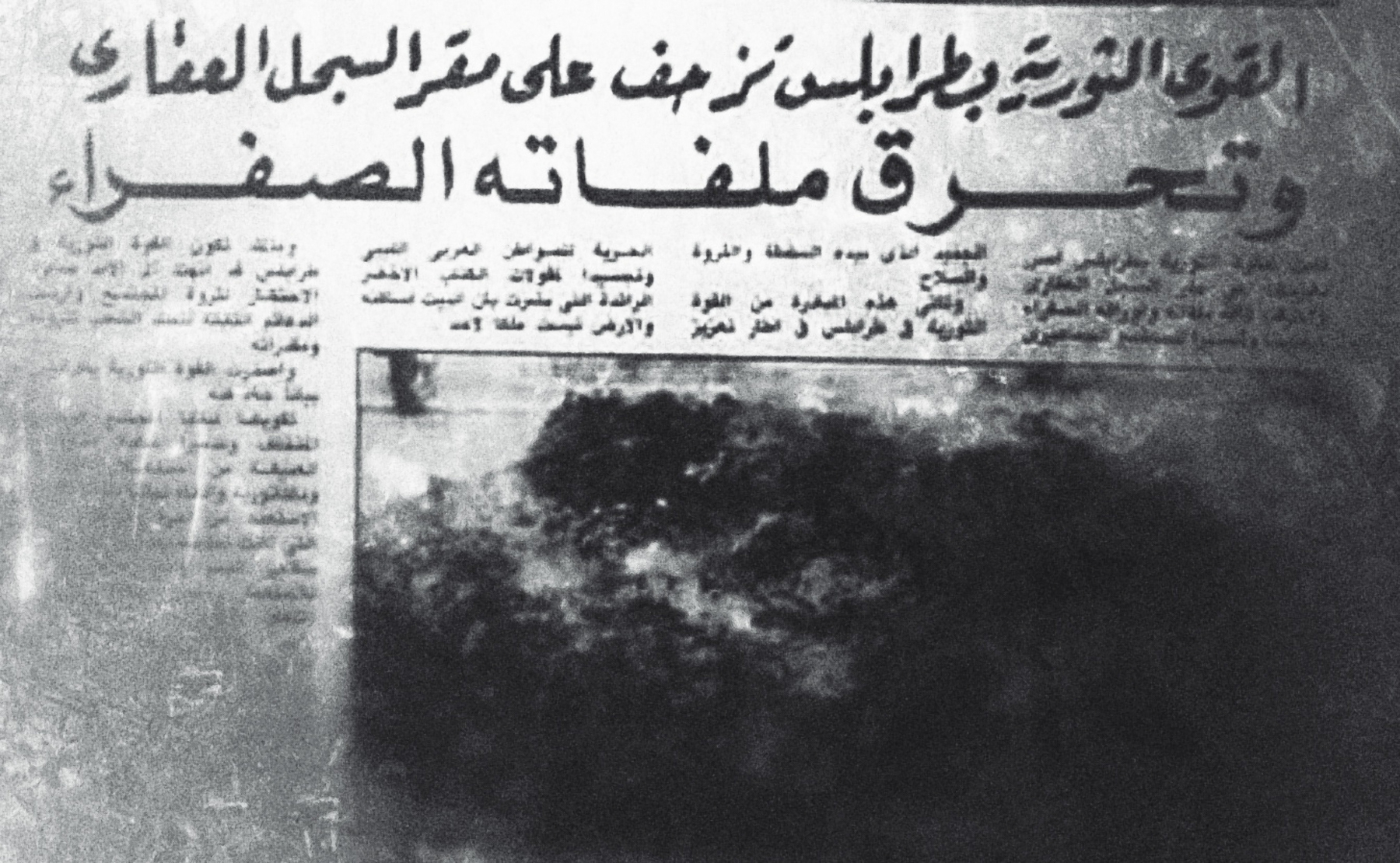

At the time, the country was under a totalitarian system. No voice could outweigh that of General Muammar al-Qaddafi. His theories and ideas constituted ideologies that we had to follow, whether or not we actually wanted to. The idea of renting was a big crime that went against the regime’s policies, including the new policy that a house belongs solely to its owner. Qaddafi eliminated the notion and respect of personal ownership and the rent system.

Perhaps the Old City of Tripoli remained outside the state’s field of vision for a while. But eventually it was under the microscope for purely political reasons, and a few of its neighborhoods underwent renovation. Nevertheless, the Old City kept its old spirit, its crumbling buildings and its people, many of whom just wanted to migrate and live elsewhere.

All the while, I was turning towards the city out of need. The regime had started compensating those affected by the notorious Law No. 4, which criminalized leasing or renting houses.

I stopped searching the Old City, but I never stopped visiting its alleyways. From time to time I revived my connection with its shops, mystical corners and its old mosques. There was the Shaib al-Ain Mosque, the Sidi Salem al-Mashat Mosque, the Qarji Mosque, and al-Naqa Mosque—my favorite mosque on Fridays.

In those days, I would frequent the gold market to exchange dollars and other foreign currencies I sometimes earned and income from my work. I believed that my belonging to Tripoli would not be complete without these rituals—that is, before I discovered the flaws in my thinking.

Sometimes we relate to things that we feel express collective identity through belonging to a place, a group or even an idea. We feel, perhaps, that we are not alone, that we are strong and capable. It is a connection that is not related to an emotional feeling. It is not a real connection that represents any entity, yet it provides us with a kind of reassurance.

I was often overcome with this feeling, to the point that I no longer cared about the details of the Old City as much as my own presence in it, or my superficial association with it at that time.

Maybe this was what prevented me, for a decade, from visiting the Kosha al-Saffar Alley, where my family home was located, to check whether it had indeed been destroyed.

I once wrote: “Have you ever tried to embrace the moment?”

I wanted to embrace important and exciting moments with all their details, noises and aromas, to become one with them.

A decade was more than enough time. The Arab Spring swept through our country and turned into a tumultuous storm. It tried to uproot us and deprive us of our personal memories and our humanity, while its wars blocked our present and future. I realized that the only thing left was the past.

Ten years pushed me to compile the past, moment by moment, in my quest for salvation. I had almost forgotten who I was, where my roots lay, if they ever existed.

Ten years reconstructed my memory, after I had shoved it into a corner. I had to rearrange the chaos inside, or at least replace it with a less delinquent chaos.

I am the son of this city, with its stones, soil, uncertainties and cold visions. No matter how much the present tries to close in on me, I can escape it to return to the past, to rebuild my memory and rediscover my roots. But this time, my purpose is to leave this present, to reconstruct a moment that is absent from reality but steadfast in my memory.

My relationship with the Old City is still a shy one. I didn’t realize how its features changed and grew colder. I didn’t notice the blue metal that gradually ate up its alleys since 2016.

I didn’t see how the history of Libya, which used to permeate every corner, began to fade, only to be replaced with the smell of money of various kinds. How the sounds of copper roads in the rust market disappeared. I could no longer hear the voices and shouts of bidders for currency prices.

Oh God, how its streets seemed to devour images and dreams!

I go through the entrance of Souq al-Mushir and I pretend to feel nonchalant. A faint, unknown voice forces me out of that state. “Come on in.” That’s usually just an invitation to buy currency. (“Come on in, young man/sir/old man, etc.”) The merchants vary from person to person, but the tone is always the same.

Before this past decade, the currency exchange shops were limited to the gold and jewelry market. There, people could buy or sell “hard currency.” Though the government officially forbade such sales, it was aware that they took place. Still, it didn’t pay them much attention.

Also before this past decade, the Old City housed several markets and famous alleyways, each with their own traditional industries and commerce.

Five years ago, the names remained the same, but everything else disappeared.

It wasn’t easy for me to roam the Old City. I saw it vanishing bit by bit, just like my memories. It was being buried in a present burdened with troubles. Everything around me became a cold blue. Blue carts, blue armored doors, blue everything. Even the blue-blood ruling class thought it could kill this miserable white city with money.

In search of home, in search of the city

I was looking for the family home and for our inheritance. Instead, I found myself searching for the whole city: Souq al-Turk, Souq al-Laffa, Souq al-Qasadirah, Souq al-Mushir, Souq al-Quraa, al-Arbaa Arsat, Zankat al-Reeh, Kawshat al-Saffar, Sharea al-Akwash, al-Kawss, Zankat al-Fransis, Sounna al-Nawl. Where had they gone?

Despite everything, the historic homes stood their ground and remained untouched by the invasion of blue. They stayed there like stars in total darkness, radiating memory, art and literature, lectures, stories and forgotten tales.

Those houses were a window of hope for what we could hold on to. How tough life is, even with a glimmer of hope! Now the city's streets have become merely a stage for million-dollar financial transactions just a few steps from the Central Bank, which from time to time issues press releases praising its great efforts in developing finance and fighting money laundering.

Early in 2019, new buildings began sprouting in the narrow alleyways. The roads narrowed further due to the influx of carts, motorcycles and Vespas—things that arrived due to the growth of the currency market and the need to transfer money quickly.

I avoided all those alleys. I tried as much as possible not to kill my dream, to hold onto it on the doorsteps of culture centers, in Dar al-Faqih Hassan and Dar al-Nuwaiji. Those culture centers constituted the cultural and artistic presence of the Old City, and they reflected the city's original identity and true character.

Early 2020, my desire to search for the family home faded, even though I continued to document the features of change with my mobile phone. Change was visible on people’s faces and in the streets, inside and outside the city walls.

I began to notice how narrow the city's alleyways seemed, the streets sticky and its images blurry. Neither my camera nor my photo-editing software could improve or beautify the scene.

With the outbreak of the coronavirus, I became more reclusive, especially with the lockdowns and travel bans. I felt that the heavy burden that I had carried over the course of a decade had doubled in just a few months. It was hard to breathe.

I remember one day I managed to evade the lockdown, and I went to the Old City. It was empty, quiet and calm, despite its bluish color. I forgot myself inside its streets. I felt like the master of the place. The calm captivated me, and my thoughts flowed strangely, interrupted only by the click of my phone camera, the sound of my gasping breath behind the mask, or the sneaking steps of passersby unconcerned with the curfew.

I don't know why I stood in front of the alley of the Alhenshiry Hotel, staring at its closed doors. They were green, or maybe I imagined that color. I’m not sure.

I wanted to relive that moment over and over again, in which I felt like the whole place was mine. After the lockdown lifted, I tried to relive that moment on more than one occasion, but I failed. In 2021, things turned a little towards optimism, as the new management of the Old City halted changes that were in process, launched a renovation of its streets in an attempt to preserve the Old City’s ancient and deep-rooted character. They worked to regulate business and remove extra floors in buildings, so the height of each wouldn’t exceed 11 meters.

I was thrilled with the change. The currency market’s encroachment on Souq al-Laffa halted, and Souq al-Qasadirah regained a bit of its splendor. Its old doors returned, albeit only on the surface. The remaining changes were entrusted to the government at large to protect this legacy. It would be a massive challenge, one that requires a mature administration to carry out its duty to protect the identity and heritage of our cities.

Home at last

As I was wandering about Kosha al-Saffar Street aimlessly, picking up the names of the alleyways one by one, when I found myself facing the alleyway where my family’s house is located. I stopped a passerby and asked him about the house, mentioning my family name. He pointed to a nearby building and said, “This is it.”

What a surprise! The house stood proudly before me, and despite its poor state, it had not collapsed, instead remaining somewhat the same. The big family home, just as I had imagined it. I stood before it, smiling. Only 11 meters separated us—11 meters, the height which modern buildings in the Old City may not exceed. Yet, I could not reach it. How did I not do this 20 years ago? How did that distance rob me of all those years? But now I don't care, for here I was standing in front of that house and conversing with it. Hello, is that you? Are you the one on whose walls the imaginations of my grandfathers, my uncles, my uncle's wife, their sons and daughters, and my father are depicted?

I started imagining what the house might look like from the inside as the man I had stopped told me about the enormity of the interior and the beauty of its traditional architecture. He said that if I had the proper papers, I could head to the Old City management. Perhaps I could claim ownership.

The man was talking a lot, and I was nodding my head in agreement with much of what he said, but I didn’t really care. Eleven meters separated me from the house.

Suddenly, I no longer felt the desire to move forward. I no longer wanted to dig deeper in my search or even enter the house. My memory formed a perfect picture of it, a picture full of joy, warmth and happiness. I saw the arches decorated with ornaments, mosaics, ivory marble, sunlight beaming into the lower and upper floors.

I didn’t fully reconcile with my present. Indeed, it wasn’t a physical home I was after, but rather a sense of belonging—one that reflected a past whose beauty I had dreamt of, despite knowing I might find a different reality.

Perhaps one day I will enter that house, or continue to search for my father’s properties. But until that time comes, I will remain grateful to this city. It has rescued me and lifted me out of my despair many times when I was ungrateful to it, when I denied the goodness of its residents of all stripes—people who cemented in one way or another the authenticity of this place, where people from different corners of the world intermixed throughout history, leaving their traces and landmarks.

I don’t think we are close to stability in Tripoli, but I always have hope in the few who aspire for change, the resilient few who have faith. Please hold on to your dream, no matter how bitter and harsh we are.