In a Berlin café, engineers Amal Mohammad and her partner Mowafaq Nirbia sat together, trying to recall the events that occurred more than four decades ago in the cities of Homs and Damascus—turbulent days that reshaped Syria's history and paved the way for the current challenges Syrians face in Turkey (July 2024) amid campaigns of racist persecution. Despite the grim memories, they speak with enthusiasm about the year 1980, a time when the pulse of democratic civil life still faintly beat. They recall political statements placed on bus roofs and scattered across the streets of Homs, and political audio recordings copied and distributed in secrecy. They remember sleepless nights spent in meetings and on the streets, fully aware of the profound implications for Syria’s present and future. All of this took place as Hafez al-Assad was tightening his grip on professional unions—entities he had previously not dared to interfere with so aggressively. He saw these unions as a significant threat to his power, comparable to the threat posed by the Muslim Brotherhood and the Fighting Vanguard.

The number of witnesses to that era has dwindled, with many having passed away. Amal not only recounts her own experiences and involvement in union activities but also speaks about her late brother, Ali Mohammad, a prominent member of the Engineers Syndicate in Damascus who was punished by the regime, spending years of his life in detention.

The Eighties and the Active Union Movement

Amal takes us back to 1979, when she was working at the Cement Corporation, in an atmosphere of fear where accusations of belonging to the Brotherhood or being an agent for supporters of the Camp David Accords were widespread. This was during the regime's crackdown following the Artillery School massacre in Aleppo. Camp David resurfaced in a speech that remains vivid in her memory, delivered by her brother Ali at a meeting of the Engineers Syndicate in Damascus. He argued that the situation in Syria at the time was serving the interests of such an agreement, suggesting that Assad’s policy of silencing all dissenting voices was designed to secure his own control and his inner circle. Ali contended that ending arbitrary arrests and the torture of opponents would be enough to halt the cycle of violence—an indication of the relatively high level of political freedom that still existed in Syria back then.

The echoes of Ali’s speech reached the union in Homs where Amal repeated some of his key points in her address to colleagues at a meeting of the Engineers Syndicate. This was at a time when union conferences were being held across various Syrian provinces.

Having recently moved from Damascus to live in Homs, Amal joined the union there to practice her profession. She attended the Engineers’ Union conference at the Amir Cinema, where participants were aware of the looming presence of intelligence agents following speeches given by Ali and Salim Khair Bek in Damascus. She recalls the thorough identity checks at the entrance.

Sahel Protests. Repression Prevail

08 December 2023

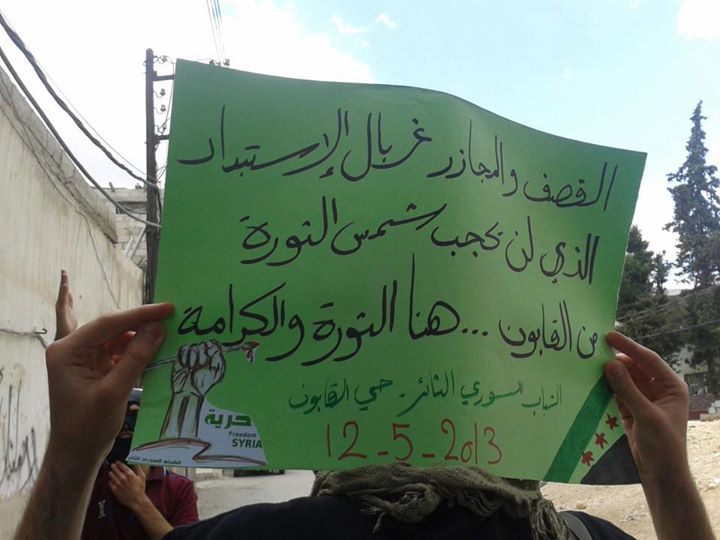

The prevailing fear seemed to stifle the atmosphere after the syndicate’s statement was read—a statement more confrontational than that of the National Democratic Rally. A debate ensued over whether syndicate members should engage in politics when Amal suddenly decided to speak. She saluted the syndicate branch and endorsed its statement, then used a clause in the syndicate’s bylaws to argue that union work could not be separated from national issues. Many in the room stood in support of her stance, which called for maintaining the union’s demands, echoing those of the Damascus branch. Amal recalls that the Ba'athists were a minority in that meeting and were nearly silenced. They even had to clear their names with the government.

Although the events of that era are often remembered in Syria as a bloody confrontation between Assad and the Brotherhood, Mowafaq, who was active in union affairs and a member of the political committee of the National Democratic Rally, coordinating closely with professional unions, supports the testimonies of other activists from that pivotal year in Syria’s history. He confirms that, at the time, the discourse was not neatly divided along Islamic, democratic, or leftist lines, and that the Brotherhood’s influence was not as significant as commonly perceived. Instead, the non-violent movement had a national democratic character, involving professional unions, democratic forces, and intellectuals, although some participants were Islami. He emphasizes that the key figures of the time, particularly in the legal fields, had experienced Syria’s democratic period in the 1950s and held considerable social influence.

Joseph Daher, a university lecturer specializing in political economy at the Universities of Lausanne and Florence, confirms in a phone conversation with SyriaUntold that historically, the Brotherhood did not have a significant influence on the union movement. The orientations of unionists were more leftist, independent democratic, or Nasserist-nationalist.

Researchers and historians trace the emergence of union activity in Syria to the 1920s and 1930s, during the French mandate, which sought to limit union involvement in politics. The union movement took shape in the 1950s and continued until the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period marked by President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s dissolution of unions during the era of the United Arab Republic.

In a research paper titled “Syria’s Trade Unions Under the Scope,” prepared for the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Daher notes that the nascent Ba'ath state, led by Hafez al-Assad, officially declared at the General Federation of Trade Unions conference in 1972 that the unions’ goal was "political," imposing strict limits on any independent political role they might play. Movements expressing social and economic demands were labeled as "destructive" and disruptive to the socialist path.

When Assad’s regime faced an existential crisis in the late 1970s, it effectively responded to the armed conflict with the Fighting Vanguard and the Muslim Brotherhood through counter-violence, arbitrary arrests, and massacres. However, it struggled to address the challenge posed by intellectuals and professional unions, led by the Lawyers’ Syndicate, which opted for civil democratic struggle with clear demands. After Assad attempted to contain the unions through backdoor negotiations led by his new Prime Minister Abdul Rauf al-Kasm, who convinced union leaders to postpone a strike set for 31 December 1980, for two months with promises of addressing their demands, Assad seemed to have made up his mind. When the unions proceeded with their strike on 31 March 1980, he ordered the arrest of dozens of union members and authorized al-Kasm’s government to dissolve the unions, which occurred on 10 April of that year.

The non-violent movement had a national democratic character, involving professional unions, democratic forces, and intellectuals, although some participants were Islami.

Accounts from those who witnessed the strike indicate that the professional unions in Homs, Aleppo, and Hama carried out the strike. However, strong ties between merchants in Damascus and Assad weakened its impact, as Assad had made favorable promises to them.

The regime’s attempts to "democratically" control the unions through its candidates also failed at the time. Mowafaq recalls three competing blocs in the Engineers Syndicate elections in Homs: the Islamic bloc, the democratic bloc, and the Ba'athist bloc, with the latter being the weakest. A mix of those with Islamic and democratic leanings ultimately succeeded.

The Abortion and Suppression of Union’s Movements

Mowafaq, a member of the Communist Party (Political Bureau led by Riad al-Turk), highlights the significance of the speeches delivered by Ali and his colleague Salim Khair Bek in March 1980—a critical month in Syria’s democratic and syndicalist movement. Key events during this period include the National Democratic Rally’s statement on 18 March, which demanded democratic reforms (such as lifting the state of emergency, modernizing the constitution, withdrawing military forces from cities, and either releasing detainees or granting them fair trials). Additionally, Hafez al-Assad’s threatening speech on 8 March (perhaps comparable to Bashar al-Assad’s 30 March 2011 speech) and the aforementioned syndicate strike also marked pivotal moments. Mowafaq notes that the demands during this phase of democratic struggle were not only political but were fundamentally related to human rights, making it natural for unions to adopt them. He explains that while a lawyer could then call for lifting martial law, such demands later became grounds for execution. With the arrest of syndicalist, political, and cultural figures involved in this democratic movement, an era of relative freedom and functional judiciary came to an end, an era that later generations would not experience.

Mowafaq, who was a friend and classmate of Ali at university, explains that Ali, with his leftist inclinations and passion for cinema and poetry, was deeply involved in the syndicalist movement in several ways. He was a university lecturer at the Intermediate Institute for Electricity in Damascus, had strong connections with the Engineers’ Syndicate and its activities, and maintained friendships with figures from the cultural and artistic circles following Hafez al-Assad’s coup. As a result, when the professional unions were active during that period, his voice, alongside that of his colleague Salim Khair Bek, was influential in the syndicate meetings in Damascus.

Amal recalls that Ali, who was not affiliated with any political party, was closely associated with the National Democratic Rally at that time. He was arrested a few days after delivering that speech in front of the rest of the teaching staff on their private bus—perhaps as a cautionary example to others.

Amal and Ali were children of a socially prominent figure belonging to the Alawite sect, a fact that drew additional ire from senior regime figures. Like other detained syndicalists from various provinces, Ali was transferred to Sheikh Hassan prison, where he spent two years before being moved to Qala’a prison. When Ali’s father attempted to visit him at a State Security branch, Major General Mohammed Nassif, the branch chief, asked if he knew what his son had said. The father replied that he was proud of his son and that it was the authorities who needed to reconsider their actions, then he met with Ali, as Amal recalls.

Protests in Sweida: From First Bread to Last Freedom

09 October 2023

When Amal visited her brother for the first time in Qala’a prison, her brother-in-law Farhan, a political detainee who spent two decades in Assad’s prisons, was also held there. Amal brought books and food, accompanied by her child Urwa, who met his uncles for the first time in that grim setting.

During visits, Ali refused to allow the family to intervene for his release, declining to sign a petition for clemency despite the threat of transfer to the notorious Tadmor prison. Despite harsh conditions and ideological and religious clashes in prison, he confided to his family that he formed strong bonds with fellow detainees, especially syndicalists from Aleppo, who visited him after his release. He also recounted moments of humanity in prison that stayed with him until his death, such as when a group of people from Hama were prepared for transfer and execution. Among them was a 13 year-old boy who turned to Ali, ran to him, hugged him, and wept.

Ali was released after three and a half years of detention without trial, like most of the syndicalist detainees, during a period when Hafez al-Assad sought to appear conciliatory following his power struggle with his brother Rifaat. Amal confirms that although severe threats before his release marked him, warning him against any return to political activity, Ali remained principled until the end. He later returned to work in human rights with the Syrian Human Rights Society, which was active in the 1990s and during the Damascus Spring.

It’s worth noting the pressure exerted by the Arab Lawyers' Syndicates on the Syrian regime, which eventually led to the release of the last detained lawyers, including the head of the Aleppo Lawyers Syndicate, Salim Aqil, Abd al-Majid Manjouna, and Thuraya Abd al-Karim. Meanwhile, some Engineers’ Syndicate detainees remained imprisoned for twelve years until the early 1990s.

Daher believes that one of the many impediments of the Syrian revolution was the opposition’s neglect of social and economic issues and the independence of syndicates.

Syndicalist figures, even those with an Islamic background, argue that the civil and syndicalist movements could have continued resisting Assad’s regime if not for the violent tactics of the Fighting Vanguard. Assad exploited this group’s actions to label all his opposition as terrorists—a strategy echoed by his son during the 2011 revolution.

The debate that took place during the peak of the syndicalist confrontation with the Syrian regime in the 1980s—about whether syndicalists had the right to intervene in political life—has been ongoing since the early 19th century and continues to this day in various countries worldwide. University professor Joseph Daher explains that syndicates played a crucial role in the fight against dictatorship in Brazil, for example, and in the democratic struggle in Poland. He believes it is natural for syndicates to have democratic demands, as it is impossible to separate them from social demands. They cannot effectively perform their role without a degree of freedom that allows them to call for strikes, for example, otherwise, their existence becomes meaningless.

Syndicates and the Syrian Revolution of 2011

When the Syrian revolution began, there was no strong syndicalist movement comparable to those that played significant roles in other countries where revolutions toppled regimes, such as Egypt and Tunisia. This absence stemmed from the lack of independence within Syria’s syndicates, which had long been reduced to mere extensions of the regime’s security apparatus. Nevertheless, desperate calls against the regime’s violence were occasionally heard from syndicate members, such as lawyers in Aleppo. These efforts were quickly met with repression, similar to the regime’s crackdown on other parts of the protesting population. For instance, in March 2012, Agence France-Presse reported that security forces dispersed a solidarity sit-in by hundreds of lawyers at Aleppo’s Justice Palace.

Daher believes that one of the many impediments of the Syrian revolution was the opposition’s neglect of social and economic issues and the independence of syndicates. Opposition leaders from groups like the Syrian National Coalition and the Syrian National Council, along with opposition parties with leftist backgrounds, largely ignored these concerns. Despite the historical significance of syndicates, these leaders did not object to the presence of regime representatives in the World Federation of Trade Unions, choosing instead to focus on gaining recognition in United Nations institutions.

Daher also criticizes the lack of independence in professional associations formed in opposition-held areas, where security and political instability were compounded by shifting territorial control. These associations were often closely tied to opposition institutions, which themselves were influenced by the Turkish government or other affiliated opposition bodies. In northeastern Syria and in the Autonomous Administration areas, the situation is not much better, as highlighted in the Friedrich Ebert research paper.

A report released by the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) in late May, titled "The Syrian Interim Government Entrenches Its Control Over Professional Syndicates and Strips Them of Their Independence in Northwest Syria," further underscores the compromised state of alternative professional bodies in those regions.

The plight of Syrian workers in Turkey, who endure harsh working conditions, is a stark example of this problem. They lack any meaningful entity to defend their rights, a situation exacerbated by the Syrian opposition forces’ preference for appeasing their "Turkish ally."

The Sweida Movement and the Revival of Syndicates

While the conditions for syndicalist movements were not favorable in 2011, the situation has become more conducive in Sweida since late last year. A cross-sector movement emerged, involving engineers, lawyers, and others, who have taken to Al-Karama Square. Notably, the regime has been cautious in its response, refraining from the typical suppression tactics.

From the outset, banners prominently called for the restoration of syndicates, emphasizing that they should return to the people. It is difficult to gauge the extent of opposition membership within the syndicates or how many members remain loyal to those elected under Ba'athist-controlled processes, or simply remain neutral.

Imad Masoud, a civil engineer active in Sweida's syndicalist movement, shared in a phone interview that he joined the movement about two weeks after it began. Together with his colleagues, they established the "Professional Gathering in Sweida," which includes 11 entities, including professional syndicates. Their goal is to be part of the change and transform the syndicates currently controlled by the Ba'ath Party and security apparatuses—organizations plagued by corruption, nepotism, and factionalism. However, Masoud regrets that historical ideological conflicts have crept into the gathering, hindering it from leading the broader movement or connecting with syndicalists in other Syrian regions.

Imad observes a power struggle within the syndicates, with varying degrees of Ba'athist influence. The Teachers Syndicate remains tightly controlled by the party, while the Engineers Gathering, which participated in the protests, has managed to set some conditions. Imad remains hopeful that independent elections in the Engineers Syndicate can be organized by the end of this year, allowing opposition candidates to run without excluding Ba'athists. He emphasizes that they do not oppose Ba'athists winning if they do so on merit, but they reject imposed results.

When asked about their response if rigged results are imposed again, he expresses confidence in the movement's strength and cohesion, believing it can effectively resist Ba'athist interference. He recalls an incident where the movement successfully intervened to prevent a meeting from taking place that was expected to be attended by Ba'ath Party branch members within the Agricultural Engineers Syndicate.

Imad is careful to distinguish between the cancellation of recent People's Assembly elections in Sweida and syndicate elections, which he considers professional institutions.

Unlike other areas, the Sweida movement has rejected proposals to form shadow or alternative syndicates. Imad attributes this to the presence of neutral members who would be alienated by such measures, potentially dragging them into direct conflict. He argues that their efforts to reduce Ba'athist and security influence have found support even among non-opposition syndicalists. They aim for professional syndicates free from the control of outdated political ideologies that reproduce their old patterns and stifle progress, while allowing members the freedom to engage in politics independently. He denies any contact with alternative syndicates in areas outside regime control.

After ten months of protest, the movement is determined not to return to the pre-uprising status quo. A general assembly has been formed, and a political body for the movement is set to be elected. The syndicalists hope to return to conditions similar to those of 1980, when they had a voice, could speak freely in meetings, and could elect their leaders without restriction. Whether they can achieve this remains uncertain, much like the broader fate of the Syrian cause.