My psychologist told me that visiting Syria, after all these years, would probably increase my PTSD, as I would remember and relive all the painful incidents I lived before.

However, the reality was even worse than I imagined. It is hard to accept that I had to request to hide my name as author of this article, and for the same previous reason: the safety of my family in Damascus, which had already suffered enough under the Assad regime, mainly because of my activism.

The story began when I was informed that I should go to some “security facility” to give my testimony regarding an imprisoned perpetrator (of the old regime) who committed human rights violations.

I was shocked when I discovered that security facilities are still open and functioning, but also by how the invitation was phrased: “Sheikh Abu (some name) is waiting for you…”.

What would a ‘sheikh’ do in a “security facility”?

It was during the days when the events in Sweida started to unfold. On the day of the appointment, and without realising, I went to another branch of the same facility. Specifically the one where my father was detained during the era of Hafez al Assad.

After realizing my mistake, I went to the right place, and while I was waiting near the main door, many small trucks full of fighters were leaving the facility. They looked very young: all of them had very white skin, blond hair and beards, no moustaches.

After a few minutes, they let me enter and asked me to wait in a small room. About ten minutes later, an armed man came in and handed me a blue uniform of the same type women prisoners used to wear at the Adra prison. The idea, of course, was that I could fully cover my hair and body before meeting the big boss. I didn’t have the time to process or to think. I hesitated for a few seconds, and then a voice in my head urged me to wear it.

The Sheikh

The armed man brought me to a very large room, which apparently was the head of the facility’s office. In the room there were two men, and, as I discovered later, both had the title of ‘sheikh’. One of them (not the person who would interrogate me later) asked me where I am from.

He requested a detailed answer, and I realised that he wanted to guess my religion or sect. I was very annoyed, even more because the ‘sheikh’ kept looking at my toes, among the very few uncovered parts of my body.

After I answered the first set of questions, he began to take care of some paperwork. During that time, many armed individuals passed through the office, asked questions, delivered files, always addressing him as ‘sheikh’.

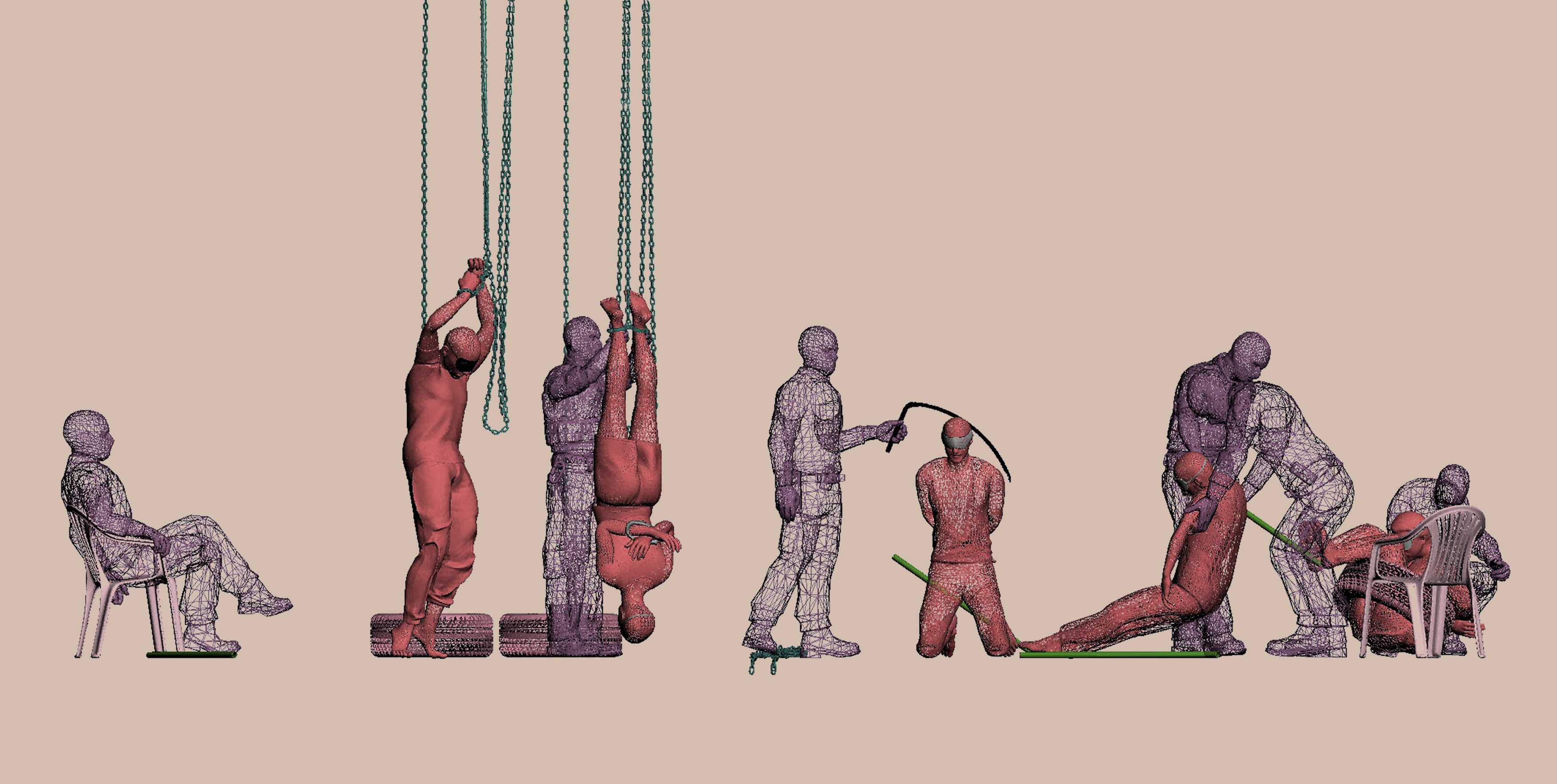

I have never been surrounded by so many weapons in a closed space, and some of those weapons were new to me. Even the two ‘sheikhs’ were heavily armed. From their conversations, I heard about some detainees who apparently went missing while being moved between the facility, the Adra prison, and the court, and no one appeared to know where they were.

This became even clearer when, after he was done with his paperwork, the ‘sheikh´ resumed my interrogation, and he clearly has neither the legal nor professional vocabulary, he didn’t possess any accurate information about my case, and he didn’t even bother recording my testimony.

I also learned that the facility hosted some women detainees, and, based on what I saw, I strongly doubt those armed men had any of the required experience, knowledge or credibility when it comes to handling them. The logistics of interrogation, the procedures, their scarce knowledge of the case they were interrogating me about, their clear lack of professional background in the field, all these elements pointed towards a basic lack of necessary knowledge to do what they were supposed to do.

This became even clearer when, after he was done with his paperwork, the ‘sheikh´ resumed my interrogation, and he clearly has neither the legal nor professional vocabulary, he didn’t possess any accurate information about my case, and he didn’t even bother recording my testimony.

After I answered his questions, he summoned another man to escort me to another investigator.

Reliving the trauma

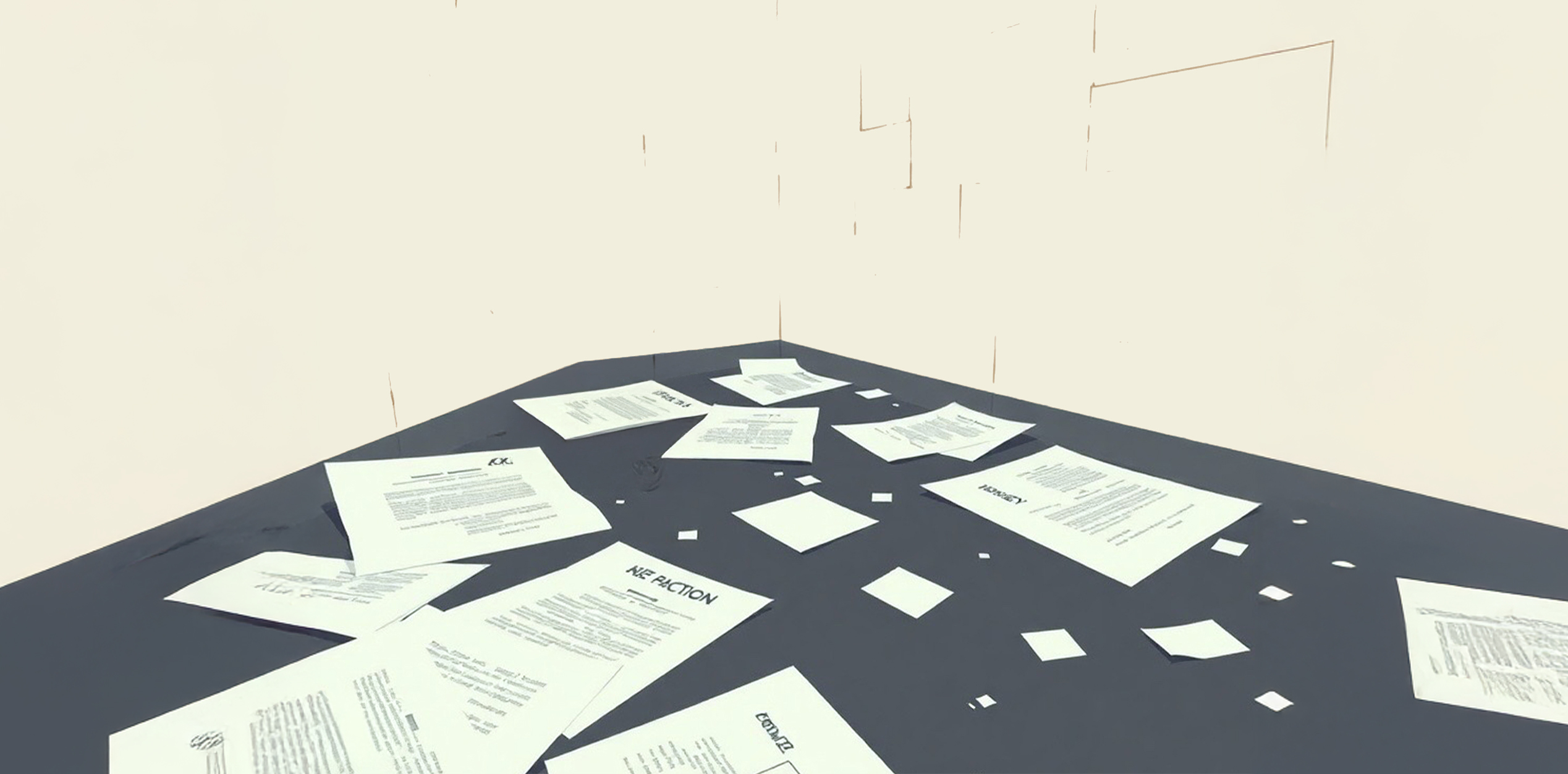

The escort took me to a separate building. The structure was partially burned. The floor inside was full of damaged and dirty documents. We just stepped on them. I had tears in my eyes when I saw this. Those documents probably included precious data and information about disappeared people. No one, however, appeared very concerned.

We went downstairs. Knowing what ‘downstairs’ usually means in these contexts, for a moment I thought they were arresting me.

Civil Society Spotlight: Episode VI

06 August 2025

A few minutes later, we arrived at another office and the escort asked me to wait there. A very old man was inside, blindfolded, and wearing an Adra prison uniform. An armed man was also there. He suddenly yelled to my escort to take me outside, which he promptly did.

Outside, many used Adra prison uniforms were lying on the ground and I wondered why. Then a third armed man saw me and got very angry, and again ordered my escort to take me out.

Only at that moment, I very briefly saw five or six detainees, lined against the wall, arms above their heads, their shirts covering their faces. The guards were shocked almost as I was. Clearly, I was not supposed to see this.

I was terrified. They told me I should wait around an hour for the investigator to join us. I pretended I had a medical appointment and that I could not stay, but that I would come back.

While I was walking toward the main door, the uniform they forced me to wear fell down, and immediately a guy behind me admonished me to cover my hair again.

The Aftermath

And then I was out. I was shocked, scared, confused and silent. I had to behave normally for the rest of that day and the rest of my stay in Syria. I took care of all the family commitments, and I accepted my friends’ reprimands for not being available to them.

During the following days, I was completely silent inside, like I was living in a different world, wearing a different face every day. I was just waiting to come back to Europe and finally be able to experience my trauma and silence more freely.

I am still asking myself: Is it my trauma that I relived again there, or did I just get a new trauma and have to learn again how to deal with it? I am still asking myself: Does real healing exist?

But it didn’t end there. The day I left Syria to Lebanon, it was also terrifying. When the employee at the border typed my name on the computer, he had the same look that I used to see under the Assad regime. He went to the officer with my papers, and asked me to meet him. Finally, they put the stamp on my travel document.

After I was back, I remained silent for almost 10 days. I could not express my anger, sadness, frustration and disappointment, until I finally cried, cried for all the pain, for all the struggles, and for all the causes I believed in.

I was displaced emotionally all the years I was out of my beloved Syria, however, I felt more disconnected, away and alone when I was there, than in exile. I felt so disconnected that when I had to say goodbye to everyone, I lied, and promised them I would return soon.

I came back totally broken, all my enthusiasm and determination lost, feeling hopeless and helpless, wondering how to regain energy and positivity, wondering even if to continue with what I started 20 years ago.

I am still asking myself: Is it my trauma that I relived again there, or did I just get a new trauma and have to learn again how to deal with it? I am still asking myself: Does real healing exist?