“For seven days, participants work on ideas, join teams, and develop their proposals into one of the six solutions to drive early economic recovery”.

With a wide and optimistic smile, Ahmed Sufian Bayram, a Syrian social entrepreneur and author, explains the details of the Hack for Syria (22-28 February 2025), a gathering related to digital investments and labour markets organized in the country after the fall of Assad regime. The name and inspiration come from the Hackathons, events that bring together for a few days tech savvy people and programmers to find specific solutions related to the digital field.

A couple of months later, in Damascus, the Khasb (Fertile) Conference, subtitled “Steps for Growth and Development” took place. It was also aimed at promoting economic cooperation between Syrians at home and abroad.

Back in February, another initiative was held in the Syrian capital: the SYNC 25, organized by Syrian-Americans working in California's Silicon Valley. Once again, the focus was on exchanging technical knowledge between the diaspora and Syrians inside the country. In a second edition in August, the SYNC conference was hosted in Damascus countryside, Latakia and Aleppo. One of the meetings was attended by Mohamed Yasser Burnia, the minister of Finance, who emphasized that digital transformation is the hope of Syria.

The same summer, the Junior Chamber International Aleppo, an organization led by young entrepreneurs with its headquarters in the US, launched Silicon. Igniting Syria’s Digital Future, a conference aimed at highlighting “Syria’s shift toward becoming a regional hub for technological innovation”, as the dedicated website states.

Following the end of the Baathist dictatorship, these types of events quickly multiplied and they all had one goal in mind: To assess the postwar situation and explore investment opportunities in the tech sector. What triggered the organisers was a combination of different factors: the improved security situation, the possibility for many in the diaspora to return, the prospect of lifting the economic sanctions, and the promise of future investments on infrastructures.

Syrians and Tech: an old story

The strong relationship between technology and Syrians dates way back. Paradoxically, the technological and media closure operated by the regime, which, for example, delayed the introduction of the internet for several years, made Syrians particularly thirsty for new tech in the following years.

When Bashar al Assad began his rule with claims of modernization, he allowed certain tech services in but left many others out. This pushed many people to look for creative solutions and tech-savvy workarounds from the very start. Many Syrians fell in love with this new field and decided to specialize in the information and computing sectors in universities or through private classes. Soon, a well formed workforce emerged. Many decided to leave the country to find better salary conditions, while those remaining mostly ended up working for lower wages for regional companies. Whatever the case, the tech domain remains among the few ones offering the chance to earn an income at regional rates. Moreover, IT and tech enable people to dream of creating new inventions and launching business startups.

Today, in a very different political context, the attractiveness of the digital field appears to have remained the same. Both the public and private sectors are racing to achieve a digital presence, experimenting with smart solutions and entrepreneurship. The Ministry of Telecommunications recently announced an alliance of incubators and accelerators, allowing applications to be launched without the need for licences. The same Ministry announced a project to bring optic fiber cables directly to homes and offices as well as the intention to launch a 5G service, even if only at an experimentation level. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour is introducing an app to connect employers with job seekers, although new job opportunities are not yet available outside of the state and humanitarian organisations.

At the Syrian-Saudi Investment Forum, on July 24, a key agreement to pursue collaborations on cybersecurity and communications for around 1 billion Euros was announced.

The government is apparently considering digital investments as a fast track, or a shortcut, to economic recovery despite, or perhaps precisely because of, its inability to lift Syrians out of their harsh day to day reality.

After all, the interest of the new authorities in Damascus for digital services is not new. The app Sham Cash was developed already in Idlib under the so-called Salvation Government as a payment platform for bills, police fines, and university fees. Beginning from July, Sham Cash has become available at the national level. As a Syrian official reportedly told French newspaper La Croix, the intention is to “digitalise 98% of the public services in four years”.

As for the private sector, their attempts are until now limited to a few options: interviewing officials about collaboration opportunities; assessing the current state of the digital sector, and, as we have seen, organising conferences.

A new generation of tech entrepreneurs

The Hack for Syria and the Khasb conference have been held in a hybrid format, both virtual and physical, to ensure the participation of Syrians from the diaspora. “There is a thirst for innovation, and young men and women want to rebuild the country and help it recover”, says Haifa Yassin, one of the organisers of Hack for Syria, in an online introductory session. “About 2,000 people in more than 35 countries will participate in workshops in ten governorates. Our event is not just virtual, people are on the ground”, he adds.

Behind Hack for Syria there is a group of young digital entrepreneurs, like Ahmed Sufian Bayram, who have been working since 2013 to create Startup Syria. In the website, the initiative is presented as “more than an organization - it’s a movement to empower a generation of Syrian entrepreneurs who are ready to lead the way in rebuilding and redefining their future”. Their ideas evolved in six projects, intending to connect together networks of stakeholders: on the one hand investors, and, on the other hand, those in need of housing and labour.

Mozna Al-Zuhuri, one of its founders and a fierce advocate for the rights of detainees and refugees, describes Startup Syria as an initiative to save Syria from “being blocked: a group of entrepreneurs abroad who want to help solve health and education issues and combine the capabilities of Syrians abroad with those at home”.

Many other organizations are working with the same goal. SYNC, for example, based in Silicon Valley, California, aims at creating 25,000 tech jobs inside Syria over the next five years, connecting untapped local talent with global demand.

Building a smart digital government, promoting digital security, and combating corruption are instead the main priorities of Digital Syria, another platform combining expertise at home and abroad to support technical reconstruction and entrepreneurship.

Obstacles are still the norm

Abdulrahman al-Shaar worked as a data analyst at a number of Syrian companies. He followed the same path of many developers and workers in the digital sector: investing the first years to build a career, being exploited at home, in order to access better wages with regional or international companies later on. “The room was full of Syrians doing great things in America and Europe: scientific research, startups, leadership positions”, Abdulrahman wrote in a post about the experience of attending the SYNC’25 event. “Personally, I started asking myself existential questions - why wasn't I one of them? Are those who stayed inside limited in their options and became a ‘lesser’ version of their true potential?”.

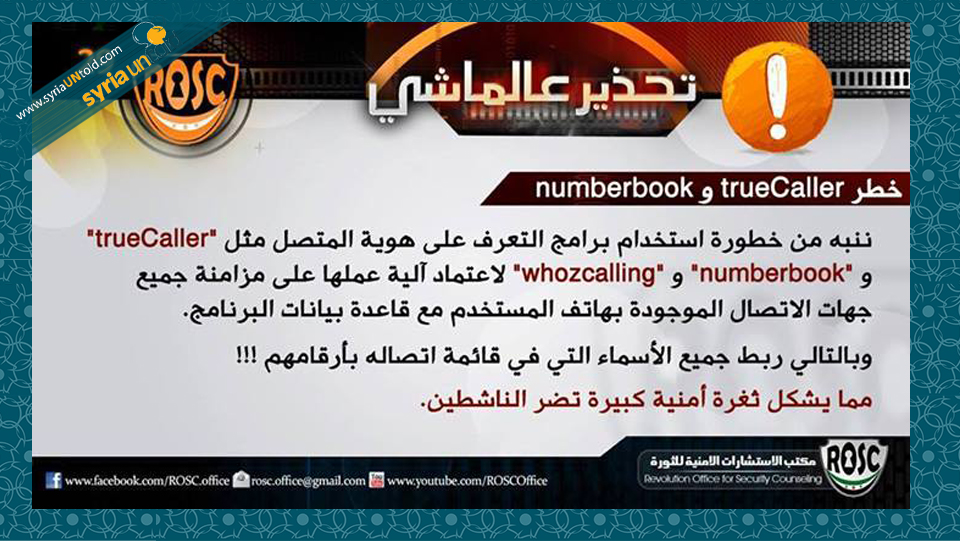

Syrians are rarely optimistic when it comes to new applications or software meddling with their affairs. The corruption often associated with them, from smart card applications to passport registration platforms, haunts their experiences. Over the years, they found ways to circumvent problems and deal with obstacles, including the regular recourse to intermediary applications to access sites that were otherwise inaccessible.

Civil Society Spotlight: Episode IV

02 July 2025

Later, the sanctions pushed companies like Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon to restrict access to different services, with heavy consequences on Syrian users, including security. Even education apps like Coursera and Udemy were banned, as were essential platforms for developers like GitHub. In the meanwhile, the state prohibited access to opposition or critical content. In this period, Syrians were using local apps such as YallaGo to call taxis, Beeorder for delivery orders, and Kamoon for online shopping, but always paying in cash, as they didn’t trust local banks and related digital services.

After the lifting of the sanctions, the access to applications is gradually, if slowly, being restored, but it still constitutes a challenge.

The technological bans are not the only obstacles: lack of energy power remains a major impediment; low living standards are a barrier to acquire the necessary equipment and applications; illiteracy in the use of smart devices and computers keeps large segments of the population away from using digital tools, and corruption permeates e-governance. Just to give an example, all along the past few years, if Syrians wanted to apply for a passport, they had to register through a digital platform to get an appointment, only to discover it was practically impossible, unless they would pay ‘somebody’ to resolve the issue.

Economist Anwar Hammouda describes the challenges of engineers around him who are investing in the so-called cryptocurrency mining farms or artificial intelligence servers. In the current situation, he says, generating the needed electricity increases construction costs, but dispensing with it ends disrupting operations and reducing profit margins. “Digital investment in Syria right now is like trying to build a house on shifting sand” he says to Untold. “The ambition is there, the talent is there, but the foundations are unstable, making the challenges far outweigh any real opportunities for investment on a large-scale. A more radical change in the structure of the economy and politics is the prerequisite for any future digital renaissance”.

Abdulrahman al-Shaar and other data professionals in Syria, well aware of the challenges, created a community to support data science: “How can we talk about data science in the context of a tired country, where priorities are still based on daily needs? But with every session, with every person who attends, thinks, and participates, it becomes clearer that this field is not a luxury or a fad. Data is a tool. If Syria wants to get back on its feet and build a future of justice, efficiency, and opportunities, it must treat data as a priority, not a side issue. We must instill the idea that this is possible and necessary, and we can start now.”

In the meanwhile, many tech workers are already coming back from exile, after having made their experiences abroad, in Turkey, in other Arab countries, or in the West. Some of them have begun developing apps dedicated to the Syrian market, like Dealio, which enables customers to find the best deals and offers; Halain (Welcome), a sort of Syrian Airbnb; or Jobseek, a job sharing platform. Many others will probably follow in the coming months and years.

The dangers of an excessive optimism

The founders of Syria-related digital initiatives do not lack confidence. On the one hand, this can constitute an essential resource in a country that has to restart almost from zero. On the other hand, enthusiasm and ambition should not create false illusions, especially among local young people who are looking at these digital initiatives as a path to recovery for themselves individually, and for the country as a whole.

While exploring the dream of Syria as a new tech hub in the region is perfectly legitimate, the likelihood of creating just another cheap labor market is also a possibility. As researcher Milagros Miceli explained, for example, many Syrians are already hired as data workers to train AI. Her research reveals different issues related to this type of jobs: from low salaries to heavy psychological impact (AI deals often with violent and triggering images) and complete secrecy over the final use of the data the workers produce.

As it is happening in other contexts, an unregulated opening to Silicon Valley, with its logics of venture capital and neo-liberal way of thinking, can bring some money and help rebuilding infrastructures, but it can also make Syria prone to exploitation by big tech companies and other investors, without bringing any real benefit to local people, and be at the same time detrimental to the environment.

Today, when it comes to the complex transition Syria is going through, the tech/digital aspects are almost completely overlooked by journalists (local and international alike) and the international community.

This is a huge mistake. Not only do post conflict situations offer a big opportunity to build a viable digital infrastructure that can help economic recovery, but a secure digital transition is an essential prerequisite to the development of stable democracies.

This process would be particularly important in a country like Syria, where the previous regime not only, as we said, delayed the introduction of new technologies and didn’t manage to keep them updated, but also used them as much as possible for surveillance and propaganda against dissent. During the last years, because of the regime's corruption, the consequences of the war, and the international sanctions, Syrians lived through a sort of technological nightmare, with profound repercussions on many levels of their lives. A correct management of a digital transition, including the opening to big tech companies, is not just an economic or development affair: it has a symbolic significance, as it can sign a definitive and clear rupture with the past.

As Noura al Jizawi recently wrote: “The digital transition is not merely a technical matter; it is a political choice that will define what kind of state post-Assad Syria will be: democratic and accountable, or authoritarian; successful or dysfunctional; digitally transformative and globally integrated, or outdated and corrupt”.

There are many signs the transition is being handled in a too rushed and improvised way. A forensic analysis conducted by SMEX, for example, found that the app Sham Cash has multiple flaws, stating that “is marred with technical dysfunction, questionable financial links, and a troubling lack of transparency”. In fact, the report says, the data in the app could be easily hacked or decrypted or even used as a state sponsored spying tool.

Another major issue is the necessity to unify in an ethical and transparent way the different digital systems that belonged to the different political entities in which Syria was divided.

Finally, In a regional context characterized by endemic instability, developing a sovereign and secure digital infrastructure is not so much a luxury than an obligation.

There is much at stake related to the current digital transition in Syria, both in the case of the country’s opening to Silicon Valley big tech companies and the establishment of new infrastructures and their legal aspects. In both cases, however, an inclusive approach should be adopted, and different voices, from different backgrounds, should be invited to contribute.

In particular, it is important to establish an exchange on equal grounds between Syrians from within and from the diaspora, between experts and NGOs and the government, and to assess carefully the interest of Syrians in front of big tech companies and foreign interests.

Qusai Mokled, a young IT shared Abdulrahman post about the Silicon Valley conference and added a short message: “I felt a kind of sadness or lack of appreciation because I was not among those invited, but at the same time I am convinced that real work does not start with a conference”.

The text has been translated and edited for clarity and flow by the Untold Editorial Team.