3 July 2025. In the morning, bad news arrived: the fires that ravaged the forests of northern Latakia, Syria, for three days, were now heading towards the Farlaq Reserve (الفرلق). Indeed, a few days later, on 9 July the fires reached its borders.

Issam Suleiman, an engineer at the forest department, is standing in front of the main gate with a group of colleagues, praying that the fire would not reach the core of the reserve. If it does, this would mean the final extinction of the sycamore trees, the last ones of this species in the country.

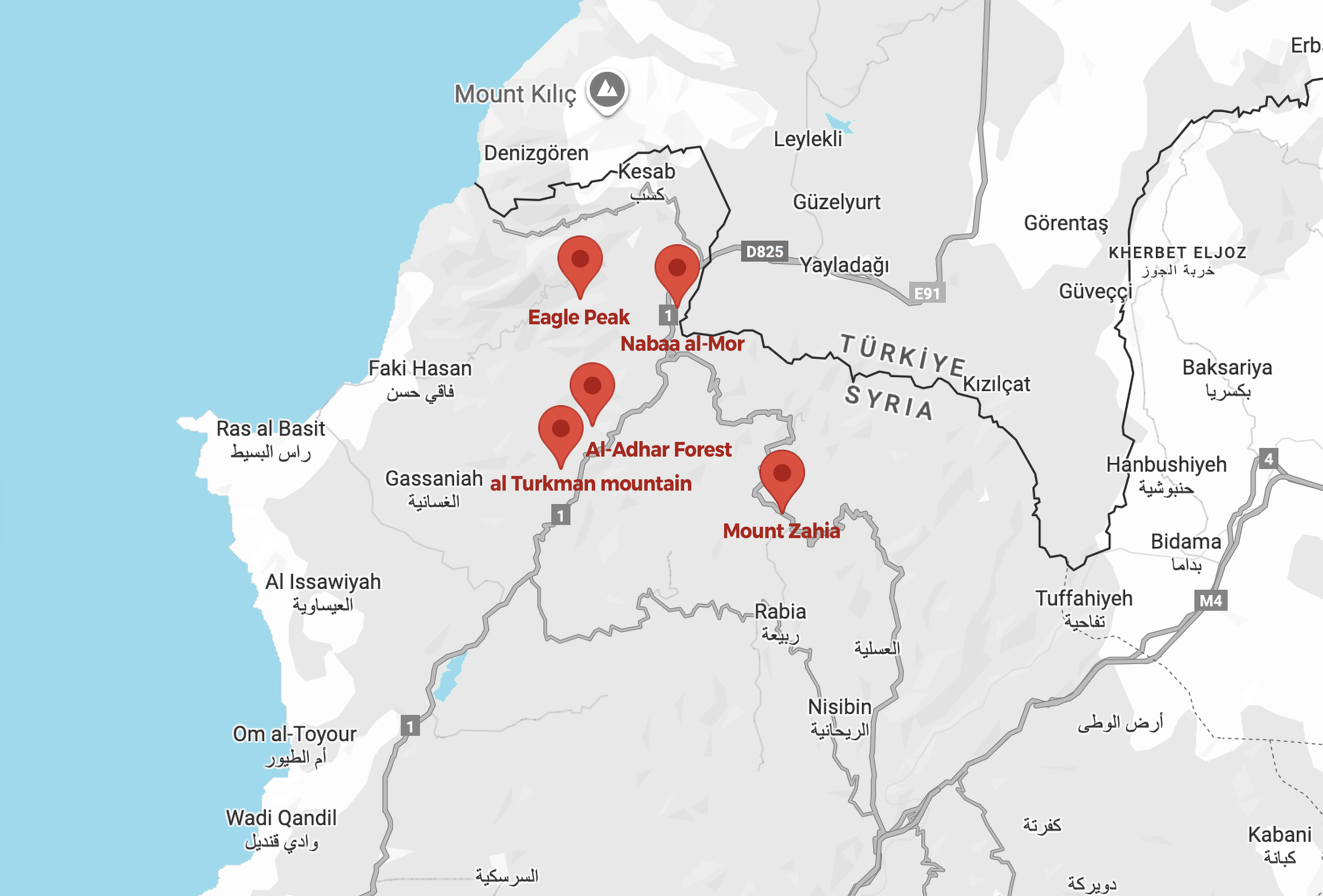

“That morning”, Issam recounts, “we watched fires break out on Mount Zahia, near the reserve, and head towards us. Winds coming from the West helped the flames to spread quickly, and could endanger the core of the reserve: the Al-Adhar Forest”.

Sycamore trees are a rare species of oak that has lived for centuries in this part of the Syrian coasts. Those still standing at the core of the reserve are only the last remnants of large forests that covered Syria thousands of years ago.

Al-Farlaq Reserve: A Living Natural Heritage

The “Farnaleq” (الفرنلق) reserve, as the people of the coast call it, holds a specific place in the memories of thousands of Syrians. The site has been visited regularly by school trips since its establishment in 1999. Located approximately 47km east of Latakia, the reserve is the largest contiguous forest in Syria, covering around 5,360 hectares.

Abdul Razzaq Al Samar, the director of Latakia agriculture department, describes the reserve as "one of the most diverse ecosystems in terms of plant (oaks, firs, and conifers) and animal (gazelle, wolves, birds, pigs, mongooses, weasels, wild cats, and Syrian squirrels) diversity, which helped to make it a major tourist attraction. It is also one of those projects that successfully combined environmental and social elements, thanks to a participatory approach aiming at involving the local community in the protection and management of the area".

On the last point, Somar Mariam, the reserve director, adds: "The participatory approach in the Farlaq Reserve is a pioneering story that combines environmental conservation with rural development. It has enabled local community participation in investing in the reserve's resources and producing more than 60 types of food, soap, and jams, providing a livelihood for hundreds of families and strengthening their organic connection with the area".

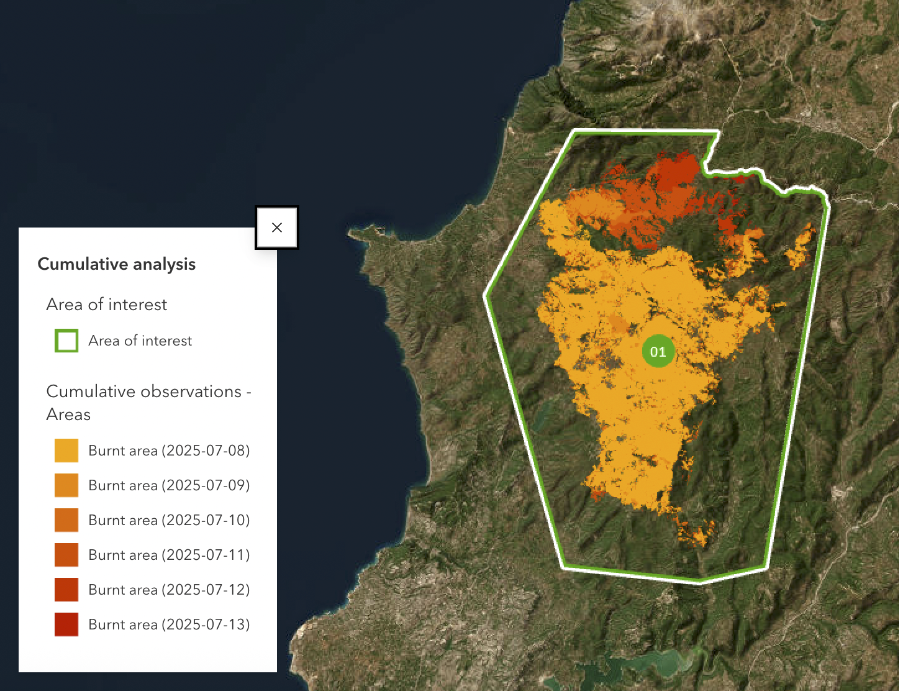

The largest fires in Syria's modern history

The fires started to spread on the morning of 1 July, 2025, in the al Turkman mountain area, northern Latakia countryside. "At first, residents thought the fire was small and would quickly subside. Unfortunately, within a few hours, the flames escalated to an unprecedented level, driven by dry, fast winds from the north, combined with temperatures approaching 48 degrees Celsius" says Issam. By nightfall, the fires had spread rapidly toward several villages and towns, including Al-Midan, Ain Al-Baida, Kasab, and the nearby Al-Saraj.

With the intensification of winds and the continued dryness, the fires spread deep into rugged, inaccessible mountainous areas, such as the Eagle Peak. Only in one day, the fire front extended for 23 kilometers. Two days later, the first international firefighting aircraft and rescue team began to arrive.

This enabled local Syrian teams to focus mainly on the preservation of the reserve area. “The first measure we took was to create a fire buffer line—an area from which trees and weeds were removed—toward the Harami Spring. We used bulldozers and teams trained in such work, people often native to the area and with over 20 years of experience” says Al Samar. About 300 workers coordinated to extinguish the fires. On the 10th, at the peak of the battle, the number reached 500, with many volunteers and teams from Turkey, Iraq, and Jordan.

Despite the reinforcements, however, the job remained overwhelming, and required the firefighters to spend several nights without sleep and entire days without food. In this context, while most of the civilians decided to leave, many remained to help. Al Samar recounts: "Some of them criticized us for focusing on the reserve at the expense of the surrounding olive and citrus trees. But we were defending a legacy that cannot be easily replaced. Fruit trees can grow again within years, but trees that are 100 years old cannot. Some of these trees are over 200 years old, which means they are older than the modern Syrian Republic (born in 1946)."

The battle, in the words of a worker on the first line, was “a battle for existence”. The most dramatic moment was on the 10th when the fires hit the outskirts of the reserve and threatened to penetrate it in multiple points. Sudden wind changes of direction made the work of the fire teams even more challenging. The fireworkers extended water hoses around the reserve, created gaps in the vegetation, and excavated holes, in order to contain the fires.

As the main reserve building was a former military headquarter, the surrounding areas were disseminated with mines and unexploded shells, which made each operation much more complicated.

In the meanwhile, according to Farhat Issa, a worker in one of the Fire Brigades, several wild animals, including deers, began to arrive at the reserve in order to escape the fires in the surrounding areas and to find water to drink. The workers had to take care of them, too.

After an extremely difficult night, the teams managed to contain the fires out of the core of the reserve. On the morning of 11 July, the fire spread from Point 45 to Mor Spring, a vital water source within the reserve and key ecological and hydrological feature, and the teams had to move with their heavy equipment away, to save the Kasab area.

In the evening, because of the intensification of the winds, new fires broke out in the Nabaa al-Mor area, named after another important spring in the vicinity. Three bulldozers were used to create a wide trench and prevent the spread of the fires. Issam says of those moments that "The smoke rising from all directions caused breathing difficulties for many of the participants, but luckily, there were no direct burns or deaths, despite the flames rising several meters and the winds changing direction several times."

Finally, on 12 July, the teams moved to Mount Zahia to complete the protection operations, removing old trunks. “By evening”, continues Issam, “after eight days of continuous work, we had secured 80% of the reserve. A damage assessment revealed that the wildfires were confined to the southern area. Meanwhile, the fire was contained to the Mor Spring after 12 hours of continuous work."

On 13 July, the final monitoring phase began, and some teams remained in the area. The reserve was damaged, especially in its southern areas, but it survived.

The aftermath

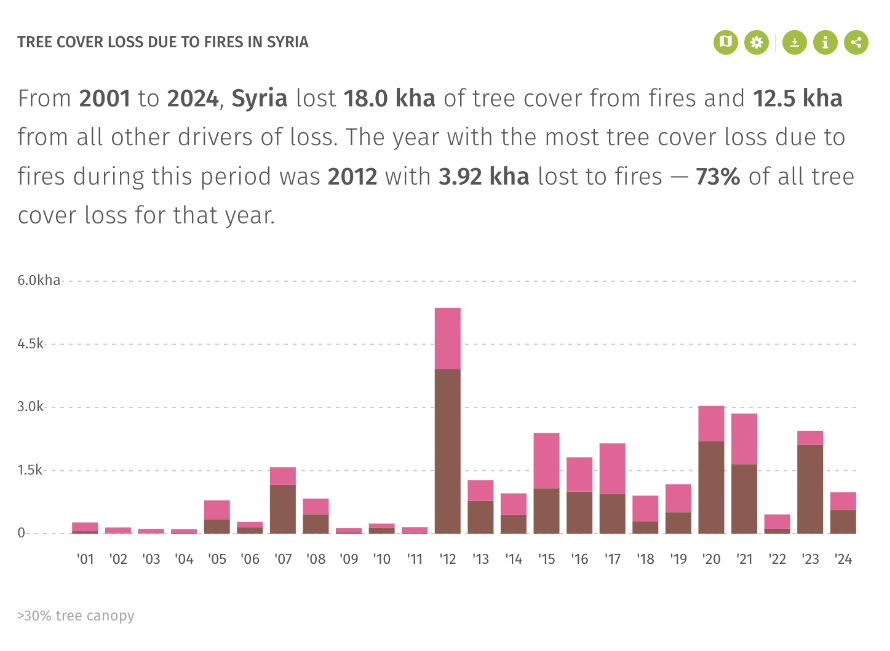

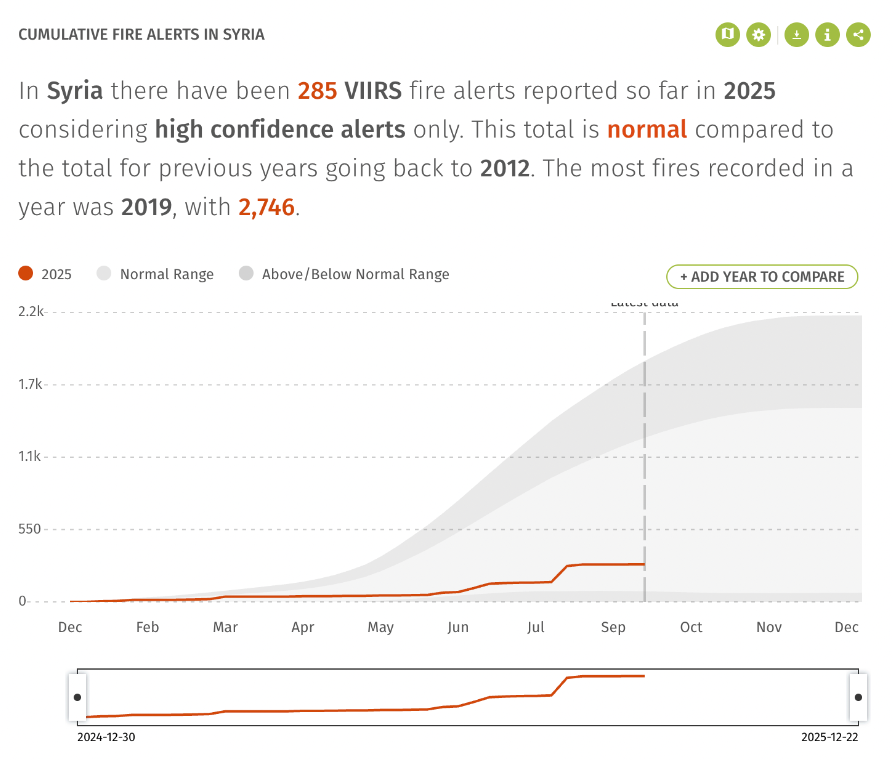

The largest forest fire in Syrian history should not appear as a surprising event. Among the mountains close to the coasts of Latakia, fires’ frequency has increased incessantly year after year, at least since the end of the 80s. After 2011, there was an escalation by 90%. Between 2019 and 2024, more than 11,000 fires broke out.

Between 2001 and 2019, Syria had already lost about 20% of its forests. Five years later, in 2024, the percentage reached 29%. In fact, Syria’s landscape changed dramatically. Today, only 2,6% of the entire territory is covered by forests. Before one century, it was 15-30%.

Behind the accelerating loss of forests in the last few years there are not only fires, but also logging and other forms of exploitation of forested lands. In general, the loss was caused by a combination of human factors (war, displacement, economic insecurity, lack of surveillance) and natural ones (high rainfall in winter and excessive dryness in summer, rising temperatures, a chronic drought). As an investigation conducted by Untold in 2019 has shown, during the last years of conflict, local people and armed militias increasingly resorted to cutting trees as a way to get better incomes, especially when alternatives became scarce or too expensive. The processes to turn wood into charcoal can easily ignite fires. Other times, fires were probably set intentionally by powerful people in order to have the excuse to sell the wood in the affected areas. The war years, with the proliferation of armed militias, saw the emergence of “wood mafias”, responsible for massive organised logging that ended with the destruction of entire forests.

Therefore, when the last wave of fires erupted in 2025, Syrian forests were already in critical conditions. The dynamics, however, were different this time, and created the conditions for the worst catastrophe of this type in the country’s history.

The wildfires broke out earlier than usual. Fire activity in Syria usually takes place mostly in August and September. This time, it began in June with a record number of 1,190 outbreaks. The main cause was the extreme weather conditions: high temperatures (in Latakia they reached 48 degrees), low levels of humidity, and dry, fast winds from the northwest, combined with the absence of rains during the spring.

At the same time, negligence, poor management, and delayed response prevented containing the effects and the spread of the fire activity. For example, some sources within the forestry and civil defense forces, who asked not to be named, hinted that reducing the number of workers and removing experienced personnel before the fire season may have reduced the ability to respond early.

On the same issue, Maher Mohammed, director of forest department, says:

"The directorate and its teams suffered from logistical and field difficulties, including a lack of equipment and problems monitoring forests due to previous political and security complications in the region. The authorities have denied accusations of human-made causes, but we cannot exclude them completely. Forest roads were not regularly cleared because of the chaos after the fall of the regime. In addition, more than 500 workers in the forestry stations have been dismissed. We currently have only 15 monitoring centers across a large area. All this deeply affected our capacity to monitor fires".

In the end, the impact was devastating: the burning of at least 15,000 hectares of forests and agricultural land, the displacement of around 17,000 residents from nearby villages, hundreds of buildings affected, the loss of hundreds of thousands of old trees, and severe damage to the region's biodiversity.

Syrian forests are in constant danger. Wildfires erupted again and constantly through August and September. In different patterns and sizes, the phenomenon will repeat itself every year, gradually destroying the remaining 2% of the forested land in the country.

The director of Lattakia agriculture department, the reserve's working team, and the forestry teams emphasized that the only way to save this important heritage is to improve its protection: “This is a collective responsibility that requires the cooperation of everyone: government institutions, the local communities, even the Syrian diaspora with its expertise and desire to contribute. Adopting sustainable afforestation programs with resilient local species, such as carob, bay laurel, and pine, not only enhances the vegetation cover but also provides the local community with economic opportunities through the exploitation of valuable natural products."

In addition, all the members of the rescue operation emphasize the importance of removing the remnants of war and establishing strategic fire lines. They also call on the Syrian diaspora to actively participate in specific environmental projects targeting al-Farlaq, not only through financial support, but also through the transfer of expertise, awareness-raising, and advocacy. We must ensure the reserve's resilience and its sustainability, they say, so that this place remains a symbol of life and renewal in the heart of Syrian nature.

This time the reserve survived, but if nothing changes, the next time it can go differently.

The text has been translated and edited for clarity and flow by the Untold Editorial Team.