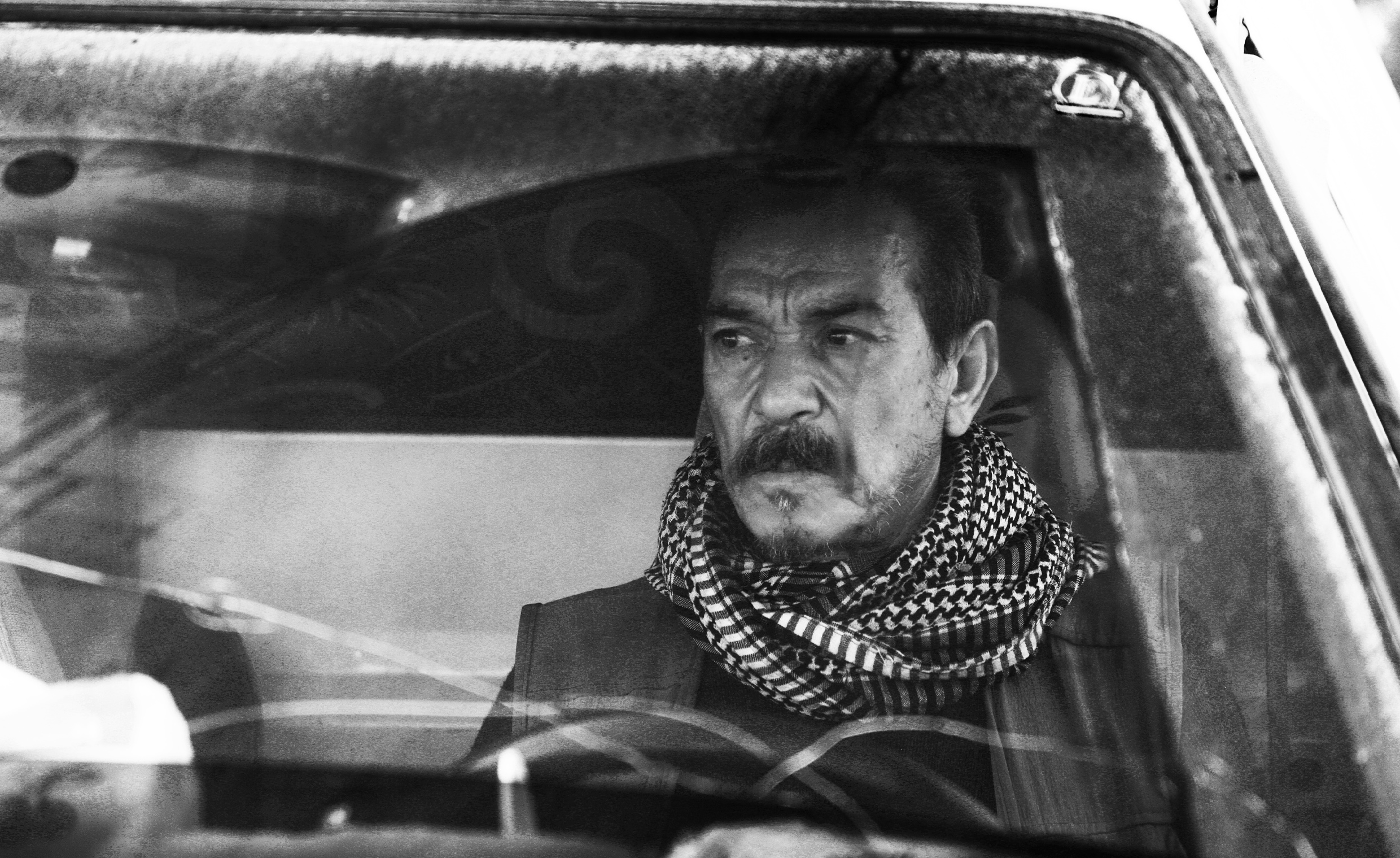

At a checkpoint in the Ithriya area between Homs and Hama, “I was wearing modest clothing to avoid harassment, and I didn't have my ID: I lost it when we left. The security officer from the interim authority saw my old photo without a headscarf on my ID card, and so he threw it on the ground. I felt angry, but the most important thing was to arrive safely and not be subjected to further violations”. This is what Rana, 29, said to Untold, using a pseudonym, as she recalls the details of the past few months before arriving in the northeastern city of Qamishli from Latakia. She was fleeing the massacres that swept through her village, where 45 people were killed in one night. It was March 2025.

“They killed everyone and then started broadcasting live after the massacre”, says her mother, who arrived in Qamishli on a visit from Tartus. Rana's family lost their livelihoods after being dismissed from their government jobs, forcing them to collect scrap metal and sell it to secure their basic needs. “We reached the point where we were picking up tin cans from the ground to sell them for a loaf of bread or a carton of milk for my little daughter. We even had to buy nappies individually”, she says.

Rana previously worked as a substitute teacher (substitute teaching is an hourly work system to cover the holidays of permanent school staff), but she stopped working for fear of being kidnapped or harmed after witnessing similar incidents involving women around her. “I saw and heard stories about killings and kidnappings of people from our area, and after a number of my husband's relatives were killed, I preferred to stay at home to protect myself and my daughter. At night, any noise outside would terrify us, and some of the images I saw on my phone of children who had been killed became daily nightmares”.

As fear grew, Rana's husband and father decided to head first to Qamishli, and Rana followed them on a safe journey.

Forced adaptation and a memory that never fades

Ahed Najjar, a woman from the city of Homs, fled with her family to Qamishli in March 2012, escaping the bombing, destruction and fear of civil conflict. “Since the war began, my home has been a shelter for more than 32 people from my husband's family. Over time, our economic situation deteriorated, our homes were destroyed, and a number of our relatives were killed, so we were forced to flee. The men in our family lived in real fear that we, the women of the family, would be kidnapped or raped as a result of the civil conflicts between the city's sects. So displacement was the best option to protect us”.

Ahed and her family chose to settle in the city of Qamishli on the advice of her husband’s friend. He told her that the city was more stable and offered job opportunities, so they moved there with 12 family members, while the rest of the family scattered to other cities inside and outside Syria.

“We fled with only the clothes on our backs, under bombardment. I never imagined we would leave our home forever. At first, the difficulties were great because of the different dialect and culture, and I was admitted to hospital because of my deteriorating mental state, but I had no choice but to adapt”.

Ahed emphasises that she found acceptance among the city's residents: “The people of Qamishli showered us with kindness and generosity, even though some voices said that as displaced persons we were taking away job opportunities. But the majority helped us to start over”.

After a month and a half, the family managed to settle in a small house, and the difficult financial situation pushed the younger members of the family to find work so that they could live a decent life. Ahed says that today she does not think about returning to Homs except for a visit: “My husband still feels homesick and wants to go back, but I cannot start from scratch again. We have built a new life here, and I married my daughter to a young man from Qamishli. This city has become our home”.

Between activism and exile

Diaa Abdullah, from the village of Al-Tha'la in the countryside of Sweida, works in programming and is also known as a poet. He was arrested before and at the beginning of the Syrian war by the former regime and was one of the first participants in the demonstrations in Sweida before the massacres took place there. Diaa travelled to the city of Qamishli to complete some work and file a report against a person from Qamishli on charges of theft. Diaa arrived in Qamishli on 12 July 2025, before the attack on the city of Sweida began on the 13. The next day, they entered his village and his family managed to leave the village, which was burned and looted, their sons killed. His village is still under the control of the General Security, tribes and groups from Daraa, as he described it.

“Since then, I have been in the city of Qamishli, with no way to return to Sweida. Although it’s possible to travel to Damascus and then to Sweida, because of the checks carried out in Jaramana at Syrian government checkpoints, and because I am wanted by the current security forces, I cannot return for fear of being violated or harmed”, he tells Untold.

He continues, “When I arrived in Qamishli, I sat down with my friends. They had accompanied me there more than 16 days earlier and were able to travel to Damascus. Based on their connections as merchants, they were able to reach Sweida. As for me, I considered my two options: either to stay in Qamishli or to settle in Jaramana. The best for me as an activist was to stay in Qamishli”.

To date, Diaa has no indication that he will be able to return to his city and his family. He finally managed to find a place to stay with the help of his friends in Qamishli, a city he describes as similar to his city, where he participates in sit-ins in solidarity with the people of Sweida. He has participated in numerous events and conferences addressing the current situation in Syria and continues his activities in the hope of returning to Sweida soon.

“I don't feel like a stranger here. Everyone is treated equally. I have met people from all walks of life and political movements, and I am constantly invited to participate in public spaces. There is great openness towards those who are different. The real pain is my forced absence from my city”, he said.

In Qamishli, Rana and her husband started working in a poultry farm for more than 40 days. “The job wasn't bad, but it was difficult for me after teaching. We worked in a farm, and over time we were able to rent a modest house”.

Rana continues, “In Latakia, I only had one room, but it was my little world. What I miss most is the washing machine. Since arriving in Qamishli, I have been washing everything by hand. I left my home with only the clothes on my back, and we spent three months in the summer without a refrigerator, longing for a glass of cold water. All I want is to go back to my village and my home, to just feel safe”.

Rana's mother insisted on staying: “Nothing has changed except poverty... The Russians have left the country, and we are left in poverty and misery, exposed to violations that amount to murder. We dream of the day when we can leave this country where we can no longer live. Our sorrow grows, even the trees are burned, and every day we worry about where we will get bread”.

Rana from Latakia, Ahed from Homs, and Diaa from Sweida — three stories searching for lost security, with memories that do not fade with distance. Qamishli, the city that welcomed them all, has become a city that brings together wounds and hope. It is an exile within the homeland that is no less harsh than exile outside it, and security mixed with the pain of hope for return.