“Radio Fresh: A Syrian History” is part of the “Meglio di un romanzo” series, curated by journalist and co-director of Q Code Magazine Christian Elia for the Festivaletteratura in Mantua. Originally published by Festivaletteratura and Q Code Magazine, this revised and translated version now appears on SyriaUntold.

The first chapter, “A Story that Begins in Idlib”, is available here.

The second chapter, “Citizen journalists despite all”, is available here.

The third chapter, “Between radicalization and foreign intervention”, is available here.

The fourth chapter, “The counter-revolution”, is available here.

Raed Fares and Hamoud Junaid, together with a young colleague, Ali Dandoush, had just left the offices of Radio Fresh, getting into the car together. The director was at the wheel and, shortly after, noticed a silver van behind them. He took a dirt road to get away, but everything had already been decided. They were waiting for them. At the corner, the van accelerated, blocking their path, and the doors slammed open. Four men got out, masked and armed with machine guns. A burst of gunfire was heard, and an instant later the vehicle had already sped away.

It was the 23 November 2018.

At that time, Kafr Nabl was under the near-total influence of Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), led by Ahmed al Sharaa, known under the nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al Julani. After years of jihadist activity across Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria, al Julani gradually distanced the group from ISIS and the Al-Qaeda network, attempting to redefine it politically.

The director of Radio Fresh was accused of violating the editorial line imposed by HTS, ignoring repeated warnings to replace 50 female journalists with an equal number of men. The station, steadfast, refused to bow to the dictates of the armed groups controlling the city, and as a result, death threats against the director intensified—especially after 21 September 2018, the day when human rights lawyer Yasser al-Saleem, to whom Raed had dedicated several posts calling for his immediate release, was arrested.

In one of them he wrote:

“Continue with this hatred. Continue with these acts of sedition.

But I warn you about Kafr Nabl.

It is tolerant and patient, but when it explodes, it is a lioness defending her children and a raging fire.

Yasser Al-Saleem was arrested in his home simply because he spoke and expressed an opinion.

He is neither a criminal nor a murderer.

Yasser Al-Saleem was arrested only because he spoke”.

For this reason, both Fares and Junaid had chosen to live in the Urb building, the headquarters of the radio station, making themselves difficult to reach. The director had planned to travel to Turkey on Saturday, 24 November, trying to be as cautious as possible. But less than 24 hours earlier, a rumor spread through the streets: “They have killed Raed and Hamoud!”

Residents rushed immediately to help and managed to save Ali Dandoush, who, sitting in the back seat, had curled up to shield himself behind the front seat. Hamoud Junaid was killed instantly. Raed Fares, still alive, was taken to the hospital. Doctors did everything they could to save him, but his injuries were too severe.

About two hours later, hundreds of residents and friends gathered at the hospital to accompany their bodies in a final procession through the streets of Kafr Nabl, first to the main mosque, and finally to the city cemetery, where they would be buried as martyrs.

Radio Fresh: A Syrian history

31 October 2025

At the international level, there came only a single post on X, then still Twitter. It was written by French President Emmanuel Macron:

"Raed al-Fares and Hamoud Junaid were killed in a cowardly way. They were the conscience of the revolution and peacefully stood up against the crimes of the regime and terrorists. We will not forget the resistants of Kafr Nabl".

In the meantime, HTS should have denounced the murders and launched an investigation. It did not. The group claimed to protect the residents but in practice had dismantled the local police, replacing them with its own fighters and imposing their regime on the city.

The day after the killing, Syrian activists launched a social media campaign against the use of masks in Idlib province, using the hashtag #remove_masks. The following day, a first demonstration was organized, an expression of the anger felt by many citizens. Many of the participants were friends and family members of Hamoud Junaid and Raed Fares, but several others also came from surrounding villages and nearby towns. However, the number of participants did not exceed 500.

For many, HTS was seen as directly responsible for the murders. The Syrian Network for Human Rights, in a later document, also suggested that HTS was at least complicit. Ahmad Jalal shared this view and, a few days after losing his colleagues and friends, decided to denounce the group on Facebook. The consequence was immediate: the next day HTS searched his house. But Ahmad Jalal was not there. He had managed to flee to the far north of Aleppo, outside the group’s control. Threats of arrest and death soon followed—though they did not come from HTS’s official channels, but from some affiliated members.

We first met Ahmad Jalal in the opening chapter as the cartoonist of the radio, but he did much more. For Radio Fresh he worked on several programs dedicated to broadcasting news, and whenever necessary he also contributed to the online website. He himself made it clear in our interview and added:

“I specialized in print media and was for a long time the editor-in-chief of the local magazine Al-Mantara. I also worked as a Photoshop instructor at the training center established by Urb”.

He met Raed Fares, Hamoud Junaid, and Khaled al-Issa after 4 July 2011, when Assad’s army had occupied Kafr Nabl. Those who had previously taken part in the demonstrations left the city, as they were liable to arrest, finding refuge in the orchards of the countryside and in the surrounding villages. Ahmad recalls:

“As the demonstrations became more frequent, banners began to appear, though at the time they were still individual initiatives by single protesters. Among them was myself, always going with a group of friends, and there was Raed, who relied on the help of his own group of friends to write the banners, despite we did not yet know each other. I met Raed, Hamoud, and Khaled when we took refuge in the countryside. We were no more than 100, and we became the nucleus of the subsequent civil and military revolutionary movement”.

According to Ahmad, Hamoud Junaid had a keen sense of humor.

“The inhabitants of Kafr Nabl are generally characterized by a sense of humor and a sarcastic style in their everyday conversations. This was reflected in the dark humor of the banners. Hamoud had the ability to bring a smile to everyone’s face even in the most difficult circumstances. Khaled was always smiling and courageous despite his young age. Raed was a unique person. He was an eloquent speaker, with a logical and forceful style in discussions and in presenting ideas. He had a strong ability to read reality and a clear vision of the future”.

A week after the killing, a second demonstration was organized. This time the participants were few—just about 30 people, mostly close relatives and friends—because word had spread that security forces affiliated with HTS would be present. Nevertheless, the demonstrators made themselves heard: they voiced their anger, and some openly accused Abu Muhammad al-Julani, blaming him for the crime. That day, along with the demonstrators, there were also ten local correspondents documenting the event. Ahmad Jalal, who was not present given the risks he faced since publicly denouncing HTS, had asked them to send him the materials from the day. Many, however, replied by saying:

“None of us dare to post photos of the protest on our personal pages. We will email you the photos, and you can post them if you want”.

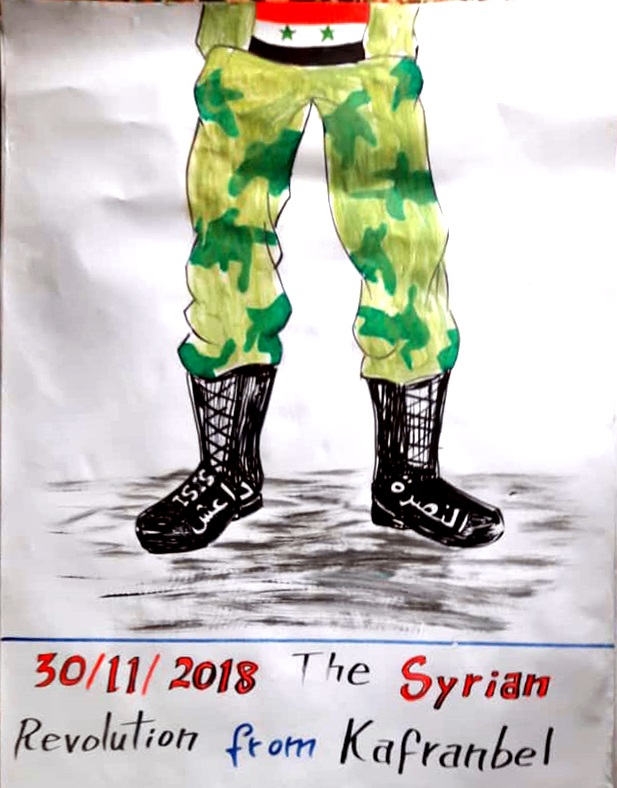

Their fear was justified. The photographic materials included the banners that had been created by Ahmad Jalal for the occasion which, unlike those of the first protest, were strong and direct. The cartoonist stated to SyriaUntold that:

“Unfortunately, they did not send me anything by email, fearing that Jabhat al-Nusra might discover it if I were arrested. So I used the photos taken by a friend and published them. I created my last drawing on 30 November 2018, one week after Jabhat al-Nusra assassinated Raed Fares and Hamoud Junaid. I knew it would be the last while I was working on it. Even if I were not arrested or killed, I would have been displaced and could no longer make drawings for the protests. […] The Assad regime, the Islamic State (ISIS), and Jabhat al-Nusra repeatedly threatened me for the same reason. It was because I criticized and denounced their crimes through caricatures and banners. The threats from Jabhat al-Nusra were different because they did not target me directly. […] I was hiding in Kafr Nabl at the home of an acquaintance. I never left the house because it was too risky. And the danger is real. I can say I live in a hole I dug for myself. Since at the moment there are no demonstrators who dare to raise my banners, I resorted to social media to criticize Jabhat al-Nusra. I had to leave Kafr Nabl a few days ago because Jabhat al-Nusra now has more time to pursue me, with its battle against the factions of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) concluded. I am now in areas outside their control”.

In fact, his last drawing made in Kafr Nabl and displayed by its citizens during a demonstration dates back to 30 November 2018. Since then, however, he has continued to draw and publish his work on his Facebook page. He sent some of his drawings to friends in Kafr Nabl who still took part in demonstrations, especially those against HTS policies in Idlib. They printed and displayed them at the protests.

Bombings and resilience

A thought increasingly shared among the people of Kafr Nabl was that the fate of the territories controlled by the opposition (whatever form the opposition took) did not depend on peaceful or armed struggle, but on international agreements. Indeed, the loss of Raed, Hamoud, and Khaled was not only the loss of friends or colleagues, but of significant revolutionary figures who had impacted the civil movement and its decline across much of the region. The peaceful protests launched by the rebels in 2011 had not lost their forcefulness, but the reality was that, by 2018, those who had created these movements—if not arrested or displaced—were now martyrs. In the words of Ahmad Jalal from 2019:

This largely affected the movement. We currently need a bold category of people capable of taking a stand and making a change. But, in the end, peaceful protests fail, but they do not die. There will always be courageous people, and we are banking on the young generation.

Although the press office had ceased to be active and the Urb organization, after the deaths of Raed and Hamoud, had been subjected to restrictions that reduced staff in its projects and activities to a minimum, the perseverance of the radio was based on the teachings of its founders, who had managed to raise a generation of activists, media professionals, and journalists capable of following in their footsteps. Mohammad al-Setif, who joined the team in 2014 as an editor and broadcaster, following the killing of his colleagues in 2018, stated in an interview that he wanted to “continue to spread the concerns of the people, serve the ideas of the revolution, and participate actively”.

Yet the moment was far from favorable. Kafr Nabl, and more broadly the governorate of Idlib, in 2019 was about to enter a dramatic period, especially because the Sochi Peace was giving way to an escalation of violence. Initially, Russia and Turkey vied for control of the governorate, but over the course of the year joint patrols began to appear, a sign of a convergence of interests between the two powers. Moreover, although the trajectory of ISIS had already come to an end in this region, Moscow continued to launch bombings, accompanied by Damascus, which intensified airstrikes. These raids forced civilians to move, worsening the humanitarian crisis in a territory already burdened with displaced people from many other areas of the country (Response Coordination Group). Consequently, the editorial team of Radio Fresh, led by Abdullah Kalidou, decided to implement precautionary measures, moving most of the equipment and staff to a safer, secret location outside Kafr Nabl, also on the advice of Abdulwarith Al-Bakour, Director of Urb and supervisor of Radio Fresh.

The official headquarters of Radio Fresh had already been hit by a barrel bomb at the beginning of May 2019, then again on 23 May by long‑range missiles, and also on 7 December by two barrel bombs. Regarding the first attack, the deputy director of the radio, Faris Ali Al Sheikh, explained that on that day there were still some employees present at the station, broadcasting with minimal equipment. The local Observatories (see chapter II) supported by the Syrian Civil Defense, managed to save them warning them in time of the attack so they could evacuate the area. The assault, however, caused extensive damage to furniture, cameras, training equipment, office materials, and the station’s main generator.

Ahmad Jalal: 'Peaceful protests ail but do not die'

25 February 2019

The Observatories’ teams also played a crucial role before the 7 December 2019 attack, evacuating the building so that the station could broadcast over the radio that helicopters—presumably belonging to the regime—were flying over the area. In this case, however, the two barrel bombs rendered the Urb building completely unusable, forcing not only Radio Fresh but also other civil society organizations to relocate to the city of Salqin, in the Idlib governorate.

Immediately after the attack, numerous videos from journalists—including Hadi Al Abdullah—activists, and citizens showed the severe damage suffered by Urb, confirmed the time of the offensive, and also revealed damage to a school adjacent to the Urb building. On this occasion, an investigative team was established which, upon visiting the site of the incident, documented the presence of a crater of one and a half meters wide and 60 centimeters deep.

The offices of Radio Fresh were covered in rubble with walls destroyed, like the rest of the offices in the building. The investigation did not succeed in definitively identifying those responsible for the attack, although witness statements and flight observation data indicated the Syrian regime as the probable culprit.

A crisis for Syrian independent media?

Despite all this, the work carried out by journalists and media workers in Syria that year was taking a different turn in the perceptions of civil society. Eight years after their birth, Enab Baladi, an independent media outlet founded in Darayya in 2011, was conducting a self‑analysis project, with the aim of engaging civil society through a survey. 21% of citizens stated that the effectiveness and incisiveness of independent media was irrelevant, 29% considered them positive, while 49% judged them negatively. The significant point is that, after administering the same survey to journalists, the results and opinions were not much different from those of civil society. 23% believed that independent media had had a positive influence, another 33% recognized a neutral impact, while 42% evaluated it negatively.

Zaina Erhaim wrote an article entitled On the anniversary of the Syrian uprising, where does the country’s independent media stand?, where she also expressed concern about the trajectory independent media were taking. If in 2011 their emergence had represented a turning point, eight years later, amid political pressures and growing internal fragmentation, independent media appeared weakened. Enrico De Angelis argued during an interview I held with him: “at a certain point covering a war, when it becomes clear that such coverage will not stop it, triggers a series of ethical‑professional conflict”.

A particularly emblematic example concerns photojournalists and their relationship with civil society. At first, many Syrians accepted sharing their pain, hoping that their testimony could help stop the war or trigger accountability processes. Over time, as that hope faded, the relationship between photographers and citizens became increasingly unstable. Enab Baladi highlighted this aspect for journalists as well, in a 2022 article, Syrian detainees’ coverage highlights state and alternative media opportunism, which analyzed the dynamics of opportunism linked to media coverage of detainees.

Zaina Erhaim further emphasized two main factors that contributed to this estrangement: the first concerns the shift in public perception of activists—initially praised for their courage, later accused of fomenting violence; the second relates to economic disparity, exacerbated by the payment in foreign currency of many professionals in the sector, which deepened class tensions with the rest of the population.

The ghost of normalization

At the national and international level, 2019 was the year in which the normalization of the conflict became most deeply rooted. Several elements demonstrate this: first of all, discussions began about reopening embassies. The United Arab Emirates reopened its embassy, while Saudi Arabia and Italy began to consider this possibility. This meant accepting and normalizing Assad’s presidency, abandoning the concept of ‘no reconstruction without transition’, born in previous years—an idea to which Europe had been tied but which gradually lost strength in the face of Brussels’ inability to achieve the desired transformation. Consequently, discussions began about Syria’s readmission to the Arab League, since it was now evident that Assad would remain in power thanks to the support of Russia and Iran. These countries, together with Syria, also benefited from the U.S. decision to withdraw from the country, which allowed them to exercise greater territorial influence—so much so that the 1998 Adana Agreement was revived in an anti‑Turkish function.

These developments gave the impression that the war in Syria was nearing its conclusion; however, the reality on the ground told a very different story. Starting with Kafr Nabl, where the bombings had become so violent that, according to Ahmad Jalal, “the entire population of Kafr Nabl was displaced before the regime’s army re‑occupied it for the second time on 25 February 2020”. This happened although 2020 was a year marked by relative military stabilization, the result of the consolidation of the understanding between Moscow and Ankara through the Astana negotiations.

The negotiations envisaged the division of Idlib: the north would fall under Turkish influence, managed by pro‑Turkish militias including HTS—which had decided to align itself with Ankara—while the south would be placed under the joint control of Damascus and Moscow.

February 6th Earthquake: How do we understand what happened and where are we today?

14 July 2023

Contributing to military stabilization was also the awareness that Assad would retain power in the absence of alternatives to his government. His re‑election in the 2021 elections appeared inevitable (as indeed it was), so much so that the President remained immune to the investigation conducted by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which for the first time attributed to his government responsibility for three chemical attacks in 2017—a condemnation that confirms al‑Haj Saleh’s theory, which we read in the previous chapter.

At the same time, however, the country was facing an unprecedented economic crisis and the arrival of Covid‑19. The economic crisis was due to three main factors, beginning with the drastic devaluation of the Syrian pound: one dollar was worth 3,000 pounds in 2020, when just a few years earlier it had been worth only 50. The second factor was the collapse of the Lebanese financial system, historically “the economic lung for Syria,” as emphasized by professor Massimiliano Trentin from the University of Bologna, who explained how the collapse of Beirut’s banking system wiped out millions of dollars of Syrian savings deposited in its financial institutions. The final blow was delivered by international sanctions, in particular the Caesar Act. This U.S. legislation aimed to block Syria’s reconstruction without a political solution accepted by Washington, in an attempt to rebalance its influence in the territory. However, these sanctions had the effect of halting the process of diplomatic normalization with some countries that were instead interested in investing in post‑war reconstruction, thereby hindering economic stabilization that could have alleviated the population’s suffering. In the words of Professor Trentin, “since 2020 living conditions in Syria, even in the Syria directly governed by Damascus, have worsened in a violently dramatic way, as never before since the beginning of the war, resulting in a real stalemate”, with the consequence that new waves of protests arose in various regions including Sweida, Jaramana, and Idlib.

Six million people were in need of humanitarian aid, especially in the informal camps of the northwest. In Idlib in particular, the United Nations documented a new wave of displaced people, whose arrival was interrupted due to the lack of security in the governorate caused by government bombings. Meanwhile, Covid‑19 had reached the country, hitting the most vulnerable regions hard. Initially, Assad denied the presence of the virus on the territory, although he had adopted precautionary measures such as closing schools, universities, and public activities. These measures proved insufficient, and the lack of adequate health facilities, especially in the northwest, worsened the crisis. Many hospitals had in fact been bombed in previous years, leaving the health system in collapse.

This aspect, in my view, also connects to al‑Haj Saleh’s theory. During the war, health facilities were systematically targeted, as documented in the film For Sama by director Waad Al‑Kateab. In addition to the destruction of hospitals and the lack of essential supplies to ensure patients’ survival, medical staff were targeted, as mentioned in the first chapter. This strategy continued over time: the bombing of a hospital in Idlib was reported by Al Jazeera on 3 December 2024, just days before the fall of the regime.

This practice, left unpunished, also spread beyond Syria’s borders. In fact, just a few months earlier, on 10 October 2024, the United Nations had published a report on war crimes committed by Israel, including deliberate attacks on hospitals. Although this event was reported in the media as something new, it had countless precedents, until the normalization of this practice allowed the threshold to be crossed without real consequences.

The destruction of hospitals and the shortage of essential supplies had severe consequences during the earthquake that struck southern Turkey and northern Syria in 2023, further worsening the humanitarian crisis in the year that followed, particularly in north‑west Syria, including Idlib and its governorate.

Within this context, Raed Fares in 2020, two years after his assassination, was awarded the “Award for Journalistic Courage”. The award was established by the Legatum Institute, a think‑tank based in London, in 2018 after the killing of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia—assassinated with a car bomb in October 2017.

“The award is given posthumously to a reporter whose death, in the past year, was a direct consequence of their work.”

And interestingly enough Iyad El-Baghdadi had already anticipated that that would have happened to the memory of Raed Fares, as for the memory of many other syrians. In his words:

“Do not let anyone tell you that there are no good people in Syria. There are, but the world chooses to ignore them while they are alive, only to celebrate them after their death”.

From that year onwards Radio Fresh had become a ghost: little funding and a downsized editorial staff. But the voice did not fade; it continued to broadcast. The director, Abdullah Kalidou, had said it clearly: “The radio is the voice of the people”.

After the fall of the regime, a new phase for Radio Fresh

“Kafr Nabl was liberated on 30 November 2024”, recounted Ahmad Jalal:

“I went there a few hours after its liberation. I had brought with me a banner I had drawn a long time before, hoping that one day the city would be freed. The drawing showed an image of the city, with the Great Mosque at the center, the revolutionary flag in the shape of a rainbow, and the faces of the martyrs: Khaled al‑Issa, Raed Fares, and Hamoud al‑Junaid. At the bottom of the banner was the inscription ‘Kafr Nabl liberated’ instead of the previous version that read ‘occupied”.

Meanwhile, the withdrawal of Russian forces had weakened the government’s defenses, while the Iranian presence dissolved in the chaos of the conflict. Assad’s government collapsed, abandoning Damascus, as rebel groups advanced toward the capital. On the night of the regime’s fall, Ahmad Jalal was in the north of Aleppo, where he still lives today because Kafr Nabl is uninhabitable due to the destruction it suffered.

“That evening I stayed up late with my wife to follow the news. At dawn, we learned of the arrival of the opposition forces in the capital and the flight of the criminal Bashar. It was a moment of extraordinary emotion. After 14 years of suffering and immense sacrifices, after feelings of betrayal, helplessness, and despair, the revolution had finally triumphed. At dawn my wife and I immediately went out to the city center to celebrate with thousands of other people. In the air there were celebratory gunshots, accompanied by songs, slogans, more songs but also tears. It was an unprecedented mix of joy, wonder, and other emotions”.

A letter to Samar Saleh: The regime has fallen, but our world remains sorrowful in your absence

15 January 2025

In the words of Abdulwarith Al‑Bakour, Director of Urb and supervisor of Radio Fresh:

“The announcement of the fall of the Syrian regime had always been a dream we had nurtured since the outbreak of the revolution. It was a moment we had awaited with impatience and for which we had sacrificed ourselves completely, so much so that its impact on us felt like a miracle. Yet, despite the overwhelming joy, it was a moment tinged with deep sadness, because those who should have been at the forefront of the celebrations were absent: Raed Fares, Hamoud Junaid, and Khaled al‑Issa. They were supporters of freedom of speech, and among the first to embark on this revolutionary media path with sincerity and courage”.

On the 8 December, Ahmed al Sharaa, leader of HTS and current President, delivered his statement from the Umayyad Mosque, and thus 2024 closed an era.

Following the fall of the regime, Abdulwarith Al‑Bakour explained that they began to expand their media experience. The idea was to bring it to all Syrian governorates according to their capacities and the available funding contracts. The first step was to open a headquarters in the capital, a strong signal and a practical act to reclaim the freedom of national media in the new Syria.

However, a setback was marked on 23 January:

“We were surprised by the announcement that the main funding contract from the U.S. government would be suspended for reasons related to the shift in foreign policy in favor of supporting media in conflict zones. This decision was a shock, not only from a financial point of view, but also morally, as it came at a delicate moment”.

The organization had to immediately begin searching for alternative sources of funding and managed to obtain some limited grants that allowed it to continue partially building the dream.

“Our work at the radio station during this period became entirely voluntary”, says al Bakour, and yet the team largely remained and continued, with determination, to carry out daily activities without pay. “Clearly, with the launch of new official channels, such as Al‑Ikhbariya Al‑Souriya and some local radio stations that emerged in the post‑regime period, several Radio Fresh employees moved to these organizations, bringing with them their experience and revolutionary spirit. It was a moment of pride for us, as these employees left an indelible mark on the new national media, confirming that Radio Fresh was truly a training ground for qualified media personnel, both in the field and professionally”.

Currently, the number of programs produced has been reduced, while the main news structure—such as newscasts and daily summaries—has been maintained. Most of the programs linked to the previously funded contract have been suspended, and with them the FM radio broadcasts, due to the inability to cover the high operating costs.

“Overall, the radio continues to operate with a qualified team that never shirks its duties despite limited resources. A system of symbolic rewards has been adopted to partially compensate employees for their commitment, while current activities include the radio’s official website and social media pages. We consider this phase simply a new beginning, a moment in which we can realize our media dream with new means and unwavering determination”.

Subsequently, they managed to obtain partial funding to run the Damascus office for four months, and are currently working with several donors to secure permanent and stable financing.

Radio Fresh believes that the next phase requires flexible and decentralized media that operate from the heart of local communities, reflect their needs, and give them a voice. The future of independent media will lie in closeness to the people, not in the circles of power. Yet concerns remain regarding independent media, as expressed by the director of Urb: “In the post‑regime era, many fear that the media may become a new tool of propaganda. However, Radio Fresh believes that its future mission is to monitor the new authorities and hold them accountable for their actions, without fear or submission, thus consolidating the concept of the rule of law”.

In the words of Ahmad Jalal instead:

“Independent media have a fundamental role to play in the future. They represent one of the achievements of the revolution, exercising the right to freedom of expression. These media can play a constructive and essential role in the work of the transitional government, with the aim of avoiding administrative errors (which are numerous due to the lack of experience and the enormous challenges faced in light of the complete destruction of state institutions). Independent media can focus on the daily problems of Syrians in various sectors and in every part of Syria, with the goal of conveying citizens’ voices to the government in order to achieve justice for them and to build the State”.