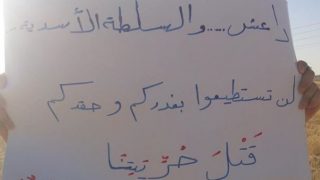

More than a year after the fall of Assad's regime, a genuinely inclusive and comprehensive transitional justice process is still lacking. Syrian human rights organizations have been critical of very poor advancement of the Syrian transitional authorities on this file.

They notably criticized Decree No. 20, issued on 17 May 2025, which established the National Transitional Justice Commission (NTJC), an organism tasked to investigate grave violations attributed to the former regime. The same ignores widespread violations committed by other actors across Syria. This logic of selective justice contradicts principles of equality and non-discrimination and excludes a broad segment of victims from its mandate. Moreover, these organizations have accused the new authorities to contribute to “a culture of impunity, allowing armed groups and forces still operating independently or under the Ministry of Defense to continue committing serious violations—including extrajudicial killings, abductions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, extortion, and sexual violence”.

It is clear that the Interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa and his allies in power have no interest in pursuing a comprehensive transitional justice mechanism. They certainly fear it would also expose them to accountability for their own crimes and abuses against civilians prior the fall of the regime and afterwards, including the massacres committed in coastal areas and Sweida.

In this framework, it is important for Syrian human rights organizations and activists to continue to raise this issue to achieve justice for the victims, but also to strengthen social peace and reduce sectarian tensions in the society.

However, the socio-economic dimension of a comprehensive process of transitional justice is generally absent from the public discourse and not often put forward by organisations, civil society, and political parties.

In a report published in 2025, UN Special Rapporteur Bernard Duhaime wrote on the need to promote “the intersection of transitional justice and economic, social and cultural rights” for States “transitioning from conflict or authoritarian rule…when negotiating, designing and implementing transitional justice processes”.

The UN Special Rapporteur added that “gross violations of economic, social and cultural rights should be identified, acknowledged, analysed and documented by truth commissions and other truth-seeking mechanisms. To ensure their efficiency, these bodies must be given the mandate, capacity and resources required for the fulfilment of their tasks”.

Recovering state assets and holding accountable those responsible for serious financial crimes should be a priority. This includes efforts to denounce privatisation of state and public assets, the distribution of public land, properties, and contracts to businessmen linked to the former Assad’s regime, at the expense of the interests of the popular class, society and public sector.

The misery of tobacco’s female workers

29 December 2025

On the contrary, instead of prosecuting businessmen connected to the former Assad’s regime and implicated in major financial and economic crimes, the ruling authorities have secured forms of reconciliation with many of them. These agreements comprises several prominent figures affiliated with Assad’s inner circle such as Mohammad Hamsho, historically a close ally and frontman of Maher al-Assad; Samir Hassan, known for his role in the regime's opaque financial networks; Issam Shammout, owner of Cham Wings, Syria’s only private airline (now called Fly Cham); and Salim Daaboul, owner of at least 25 companies and son of Mohammad Deeb Daaboul, who served as Hafez al-Assad’s personal secretary for 40 years. No legal actions have been taken to prosecute these individuals for economic crimes or to recover their wealth for the state and its citizens.

In return, these personalities have agreed to give up a portion of their fortune.

For instance, The National Committee for Combating Illicit Gains, established in May 2025, announced on 7 January a settlement with businessman Mohammed Hamsho, under its recently launched Voluntary Disclosure program. In a statement on its official website, it said the agreement came after “extensive investigations” and examination of assets and financial declarations, established to ensure property transparency and achieve economic justice. The voluntary disclosure program allows the settlement of legal and tax status “without prejudice to the state’s rights or departure from the legal framework”. The commission said it is granted to those who prove that their wealth was acquired through lawful means. According to the statement, the program seeks to enhance transparency in the economic environment, encourage investment, and protect the national economy from manifestations of illicit gain, in addition to restoring the state’s financial rights.

No transparent process has been followed by the transitional authorities regarding this and other reconciliation agreements. Indeed, what percentage of these businessmen’s fortunes have been taken? Where do these funds have been allocated? Into the sovereign wealth fund? Into the state’s budget? Specific state’s programs or investments? Or to enrich new business cronies?

The absence of transparency and justice regarding economic crimes allows for the impunity of the new Syrian ruling authorities.

The President’s brother

The Interim President’s brother, Hazem al-Sharaa, has increasingly emerged as a key figure in economic affairs and in managing business elites. He accompanied Ahmad al-Sharaa on his first foreign visits to Saudi Arabia and Turkey and was officially appointed as the Vice President of the Syrian Supreme Council for Economic Development. In addition, a Reuters’ investigation revealed that Hazem al-Sharaa, along with a small committee, has been responsible for reshaping the Syrian economy through secret acquisitions of companies previously owned by businessmen affiliated with the former Assad regime. This committee has taken control of assets worth over $1,6 billion from businessmen and companies formerly affiliated with the former Assad regime according to this investigation. Moreover, Hazem al-Sharaa’s central task is to handle relations with local businessmen and attract others residing outside the country, alongside managing investments and development funds.

Similarly, in the telecommunications sector, Syriatel, one of the largest private companies in Syria and largest country's telecommunication company, is now controlled by the committee led by Hazem al-Sharaa through a member appointed as a signatory. In addition, companies formerly owned by figures connected to the previous Presidential Palace, such as al-Burj and Opal, resumed operations under the new name al-Mujtahid Technical Company. Registered with a nominal capital of just SYP 50 million ($ 4,545), the company’s ownership remains opaque. Syria’s telecommunications sector generated at least 12% of state income prior to the fall of Assad's regime.

More generally, the transitional authorities have established new economic institutions, which concentrate power within the presidency, limiting independent oversight. Some examples are the Higher Council for Economic Development, the sovereign wealth fund and development fund. In each case, substantial powers and responsibilities are concentrated within the presidency, with minimal mechanisms for control or accountability - especially given that the parliament has yet to be established. Likewise, the Supply and Procurement Committee (SPC), established under the Secretary General of the Presidency, controlled by the President’s brother, now oversees all internal and external procurement for state institutions - potentially exerting control over contracts worth billions of dollars. The creation of the Syrian Petroleum Company in October 2025, which merged all state-owned oil institutions into a single entity, has further expanded presidential control, including on contracting, extraction, refining, and distribution across the oil and gas sector.

An attempt to understand violence in the new Syria

15 December 2025

Pursuing this orientation, in mid-November, the National Committee for Import and Export was created to supervise imports and exports. This committee is also under the authority of the Secretary General of the Presidency and is chaired by the head of the General Authority for Ports and Customs, with five deputy ministers and the director of customs as members. It could easily favour traders close to the ruling authorities.

Therefore, contrary to affirmations made by some economists and supporters of the interim government, dynamics of corruption and concentration of power are still very much present at the highest levels of the state.

Instead of encouraging donations made by businessmen formerly affiliated with the former Assad’s regime, those guilty of economic crimes should be held accountable. In other words, their fortunes and ill-gotten gains and assets should be seized to benefit the wider society and the state’s resources. They generally accumulated their wealth through illegal ways or connections to the former ruling elites.

A clear and transparent process led by a democratic and inclusive commission of professionals should reassess past contracts and privatization programs, as well as selling a significant portion of state owned lands and large private properties. Many of these operations disproportionately benefited businessmen connected to the former regime, significantly diverting state revenues. A comprehensive reassessment should uncover any irregularities or ill-gotten assets. Should such findings emerge, the companies in question should be nationalized and their management placed directly under worker control, while assets and fortunes of businessmen seized by the state.

Similar mechanisms should be applied for the allocation of contracts and state funding by the current ruling authorities. Indeed, Memoranda of Understandings (MoUs) between Damascus and foreign private entities or states are publicly announced, but critical details, such as the selection processes, standards, and criteria for awarding contracts, are not disclosed. Allocation of state’s contracts to Syrian private companies suffer similar problems. For instance, the Ministry of Finance adopted in April 2025 Cham Cash as the sole method for paying salaries to public employees and retirees. Bank Cham was established by HTS in Idlib in 2020 and is registered in Turkey. This decision was also particularly troubling because the Central Bank of Syria did not recognize Bank Cham as a licensed financial institution. Moreover, Bank Sham is managed by Mohammad Omar Qadid, who is acting as the Head of the Central Financial Control Body, although there has been no prior official announcement of his appointment. Mr Qadid has also been an influential figure within HTS ranks for years now, formerly known as AbdulRahman Zerba. He is also connected to other cases in which the transitional authorities have allocated him with state’s contracts in a clear attempt of concentration of wealth and influence in the hands of HTS-linked figures. The most significant case involves Taiba Petroleum, a company belonging to Mr Qadid that is reportedly planning to acquire the management of all gas stations affiliated with Mahrukat, a state-owned entity responsible for the transport, storage, and distribution of locally produced and imported petroleum derivatives.

The public sector

Transparency issues and achieving justice should extend to the public sector as well. Many state’s employees have been affected by decisions made by the ruling authority: limited clarity on the criteria and legal procedures were applied, such as arbitrary layoffs, reduction in salaries, or transfer of employees to locations far from their initial work and residence without any prior explanations. Recently, employees of the port of Tartous for instance staged a sit-in in December 2025 in front of the governorate building to protest their transfer to the Jarablus and al-Bukamal border crossings in the eastern governorates.

More generally, state policies such as cuts or cancellations of subsidies on essential goods, such as bread and oil derivatives, or services, including electricity, have been implemented without prior collective dialogue, imposing significant hardship on the population and productive sectors of the economy (agriculture and manufacturing industry).

These decisions directly influence who benefits and who is excluded, making it a prime source for corruption and patronage, as well as socio-economic injustice.

Alongside these dynamics, the capital accumulated in illegal ways and sheltered outside the country should also be an objective in achieving justice for these economic crimes. According to the Pandora Papers, revealed in 2021, Samir Hassan for instance maintained and even expanded offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands (Libra Investments Trading, Samya Investment, Sunset Real Estate Properties), despite sanctions imposed on him, to invest in real estate there – a Caribbean tax haven that allowed him to partially circumvent asset freezes until the gradual dissolution of these entities in 2017. Similarly, Rami Makhlouf has also benefited from these offshore companies to shelter part of his fortune.

More widely, the socio-economic component of transitional justice raises the question of the ruling authorities’ political economy, while opening the door to a strategy promoting the concept of “common good”. This concept is linked, on one hand, to a "community" of people (the general public) who decide to "collect" a resource (natural or manufactured, tangible or intangible), and on the other hand, who collectively determine the standards for the production, maintenance, and/or use of this resource. This decision does not depend on the "nature" of the good, but rather on a collective choice; and it can pertain to any type of good or service.

In other words, processes of capital accumulation and distribution, as well as economic policies should be collectively discussed in society and not limited to a small minority in power. In this perspective, the decisions of the transitional authorities to conclude agreements and reconciliations with business figures linked to the former Assad’s regime, alongside the lack or absence of transparency and decisions with a democratic mandate in the allocation of state’s funds, privatization of state assets and conclusions of MoUs and contracts, conflicts with the principles of a comprehensive transitional justice process.

In conclusion, not only the absence of a comprehensive transitional justice process betrays all the victims of human rights violations and increases political and sectarian tensions in the country, but it also fosters authoritarian dynamics and new patronage networks connected to the authorities led by Ahmed al-Sharaa and its allies. This results in an elite-led transition process and reconstruction process reproducing social inequalities, impoverishment, a concentration of wealth in the hands of a minority, and the absence of a productive development of the economy.

Social justice should be part of any comprehensive transitional justice process and agenda.