SyriaUntold republishes historian Keith David Watenpaugh notes from post civil war Syria. All pictures are taken by the author.

Cover caption: The Damascus suburb of Jobar was the site of terrible fighting and shelling (2013-2018). The UN estimates that 92% of the city was destroyed and remains uninhabited. In the center is the Great Mosque of Jobar and the Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue.

In mid-January 2026, I was able to visit Damascus, the capital of Syria, for the first time in nearly 20 years and 13 months after the defeat of the authoritarian Ba‘athist régime that had ruled the country since the early 1970s. I witnessed and documented the terrible cost of the 12-year civil war on the urban fabric of the cities around the capital and spoke with local activists and people that call those cities home. I had lived in Syria, primarily in the city of Aleppo, for much of the 1990s as a Fulbright scholar and a Social Science Research Council fellow. My time there led to my first book, Being Modern in the Middle East (Princeton, 2006) and then a large-scale humanitarian project (2013-present) the Article 26 Backpack, designed to help Syrian young people continue their higher education outside of Syria and ready themselves to return.

I share initial thoughts on the construction of the history of Syria’s recent past in public spaces and ask questions about the formation of memory in real time.

Telling war stories to make meaning

The sun was an angry little pinhead. Dresden was like the moon now, nothing but minerals. The stones were hot. Everybody else in the neighborhood was dead. So it goes. (Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five)

War histories make what is lived as fragmentary whole and episodic coherent — creating a smooth stream with clear meaning that would be unrecognizable and unintelligible to those as they experienced it. When Vonnegut went to write his story about living through the firebombing of Dresden, he worried about bringing any meaning to what had happened to him, fearing to do otherwise would be an endorsement of war itself.

People want war to mean something. How else can one explain so much personal and communal loss, and to ensure their place in the world created by that violence? Syrians are no different.

Under the Ba‘athists, establishing the meaning of the past was the prerogative of the state, which controlled all the tools of history-making, from museums and school curricula to academic appointments, archival access, and public spaces. At least for the time being, a space has opened in which Syrians themselves can write and create history on their own, though still within an emerging social orthodoxy that erases the “Third Way” of democratic reform, and the broader participation of nationalists, Leftists, non-Arabs in the war — and foreign interventions and fighters.

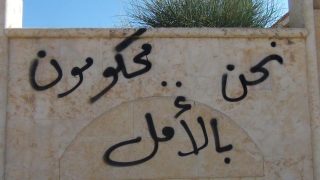

During my brief time in Syria, I was able to document two instances of forming public history. The first on the skeletal remains of a building that had been the Palestinian Red Crescent Hospital in Yarmouk Camp, and the second on the wall of a girls’ high school in the center of Daraya.

One of the most jarring legacies of the war in Syria is how relatively untouched the capital is when compared with the surrounding suburbs just minutes away, one can see utter devastation like that experienced by Vonnegut in Dresden. Attacks on these suburbs went far beyond military necessity and as I’ll write about in a following essay, were subject to chemical warfare and the destruction of graveyards in addition to urbicide.

Grapes and blood: Abu Malik al-Shami’s “Memorial to the 14th anniversary of the Syrian Revolution”

I first “misread” the mural on the wall of the Daraya Girls High School from right to left. It extends about a half a block along a wall facing the street and was painted in late 2025 to honor the contribution of the White Helmets, officially the Syrian Civil Defense, a NGO that organized to pull people from beneath the rubble.

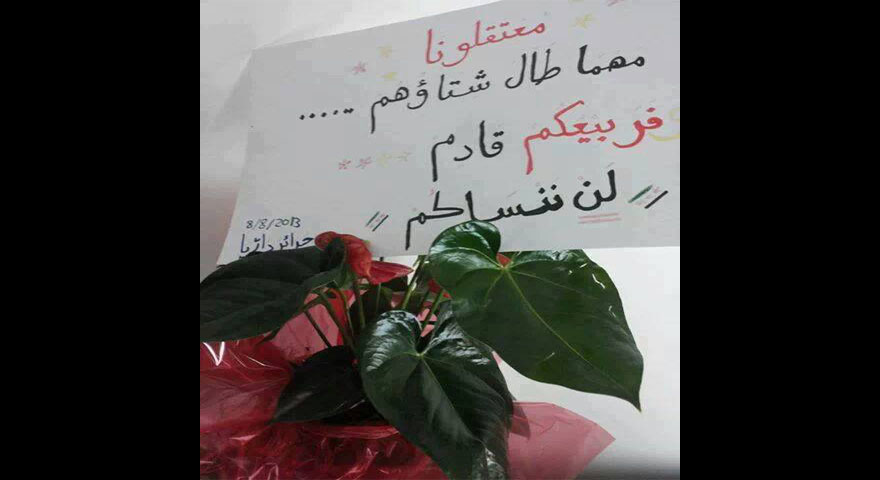

Daraya was among the first cities in Syria to join the peaceful uprising against the Ba‘athist régime and a home to a secular-leaning civil society led by activists like Ghaith al-Matar, who famously presented water and roses to soldiers. Ambushed by the Syrian secret police, he was tortured and murder in late 2011. Anti-government militias took control of the city the next year and a failed prisoner exchanged led to Daraya Massacre of August 30, 2012. The killing of over 700 civilians by the Syrian military supported by Lebanese Hezbollah and Iranian forces marked a bloody turn in the conflict. The Syrian régime imposed a starve or surrender strategy on the city. Through the siege, local committees and civil society groups embarked on innovative humanitarian efforts to mitigate the harm and employed novel cultural preservation work, including the creation of the Daraya Secret Library and other forms of “vernacular archiving.” Following years of starvation, shelling and air assaults, the city surrendered, and most of its remaining inhabitants were forcibly displaced.

Daraya today is bustling and busy, with new businesses opening and repair and restoration efforts taking place. The scars remain. Cars parked along the street obscure the mural, and it is difficult to see it in its totality. Reading as intended from left to right the mural unspools as frame of expose film from a camera. The Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution credits the mural to Syria’s most famous wall artist, Abu Malek al-Shami who painted both during and after the war and whose post-war artwork is prominent at the Martyrs’ Cemetery elsewhere in the city. This is official and sanctioned public art, at least at the local level.

In the pre-war era, Daraya was known for its grapes and was surrounded by vinyards. During the siege, the Syrian army bulldozed those vineyard.

To this point in the narrative there is no direct indication of ideology or the actions of any specific rebel or international groups; the frames’ narrative is one that most Syrians would recognize and could see themselves in.

The penultimate frame takes the mural in a different, more partisan and disciplining direction. A young Syrian colleague found this image outrageous and even offensive as it signals the definitive and unique role of the HTS, rising up from its stronghold in Idlib and swarming across the country.

This is the narrative produced by the current masters of Syria and forms the basis of its claim to legitimacy. It utterly ignores the role of other groups in overthrowing the regime and draws a false line from the nonviolence and democratic uprising of a decade ago to its anti-democratic, though quite pragmatic Islamism.

For Syrians who have looked at the mural with me, the imposition of the HTS victory is a misrepresentation that disrupts an otherwise consensual narrative, and a narrative that fosters a sense of a shared past of democratic aspiration, mass atrocity and human rights abuse, and displacement.

The “end,” or what we historians call the telos, in which the struggle of the Syrian people finds its legitimate purpose in the rise of the HTS and its version of Syria is controversial, if not a hijacking of history. With the reaction of my Syrian colleagues in mind, for that narrative to take hold it will have to be repeated and reimposed through public art, but more insidiously in the forms state-based history making that calls to mind the apparatchiks of the Ba‘athist past.

Will Syrians be able to contest this history and what forums will be available to them to do so, or will these form of dissent be forced into the realms of personal and communal memory as they were in the past?