In a landmark speech before the heads and members of grass-roots organizations and parliamentarians on 26 July 2015, Bashar Al-Asad, the current Syrian president, emphasized the relationship between sacrificial heroism, militarism, national membership and belonging. He said: “[T]he fatherland is not for those who live in it or hold its nationality, but for those who defend and protect it,” pointing out that “the army, in order to be able to perform its duties and counter terrorism, must be supported by the human element”.

Three major themes can be deduced from this speech. First, the conception of fatherland is intimately linked with the readiness to die for the nation. Second, this sacrifice requires martial ability and physical strength, by which both national membership and belonging are measured. Third, in this speech President Asad was praising the army and asking society to appreciate its accomplishments.

While this speech was given during the ongoing Syrian crisis, these perceptions of national identity and belonging are not an outcome of the Syrian war. Rather, President Assad’s definition of who deserves to be Syrian rings many bells from the past. In fact, his definition not only delineates boundaries on a national level between those who support his dictatorship or the opposition but, more importantly, it carries expectations and ideals of national identity. In other words, these notions of sacrificial heroism and readiness to die build an image of a martial man. Such a construction is not very different from what any ordinary Syrian has experienced in the last four decades.

I was initially drawn to the subject of nationalism by the importance it played in reinforcing the cult of Baathism during my primary and secondary school education. An example rich in perpetuating masculinist belonging is the compulsory conscription to the two Baath-affiliated organizations: the Baath Vanguards Organization (Tala’i‘ Al-Ba‘th) during the primary stage and the Revolutionary Youth Union (Ash-Shabibah) in high school[i]. These two organizations mobilize children through enforced training and membership in paramilitary groups that perpetuate ideals of masculinist militarism, conceptualizing them as expressions of nationhood.

More related to the cult of subjugation was a weekly compulsory session dedicated to teaching pupils about how to become an active Baathist by using a Kalashnikov, and how to show their love for both the nation and the leader, particularly through celebrating a physically strong body. This was accompanied by 15 days of compulsory summer camp that gave male students extra time to learn about the soldierly life, in an attempt to prepare them for compulsory army conscription when they finished high school. Meanwhile, female students would attend sessions that taught us about the glorious past of our nation as associated with the heroic deeds of men.

,” another example of how expressions of nationhood were identified with masculinist achievements.

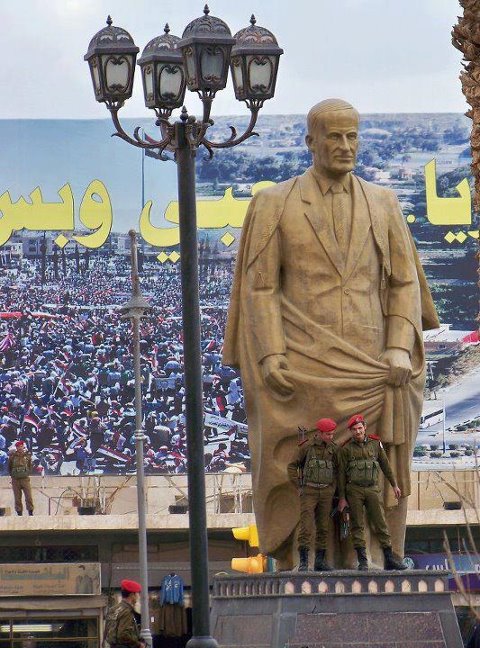

These nationalist songs celebrating the heroic deeds of men and their strength and bravery posit that the nation is an entity formed only by men’s accomplishments. In fact, these incidents used to affect my sense of belonging and identity, as if my existence was blurred by the leader’s physical strength, prowess and patriarchal authority (as Hafez al-Asad was portrayed as the father of the nation).

The normalization of militarism, masculinity and physical power in these songs is intimately linked with the sense of identity. In school, they were thrust on us every morning and during break time. Presumably, the Baath regime thought that by forcing students to memorize these songs they were inculcating and strengthening our sense of nationhood. However, to me, they were in fact consolidating gendered boundaries within the national community, its power relations based on masculinism and hierarchy.

In other words, defining patriotic belonging and masculinity is manifested by conceptualizing the nation as a fraternity, descending from one father and solidarity between the “brothers”. The paradoxical nature of considering the nation as a family is that such a notion perpetuates gender hierarchy by reinforcing supremacy of the male patriarch within both family and nation (McClintock, 1993: 63). At the same time, this national belonging is identified by men’s physical sacrifices and strengths.

Moreover, men are depicted as the ones that guard and preserve the nation, thereby intimately linking the conception of the nation with constructing physically strong men. This is directly reflected in defining the basis of citizenship as measured by men’s readiness to die for the nation and a commitment to a masculinist conception of national membership based on militarism and chivalry. The dominance of such a notion situates women as inferior and outside national memory.

The Nation of Men

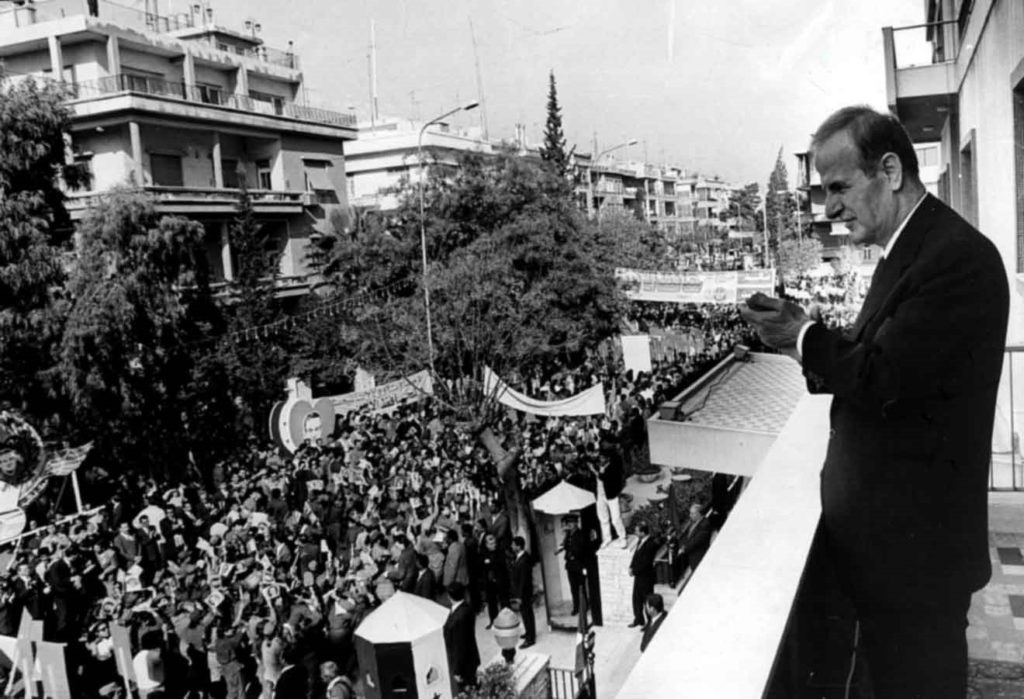

This interplay between loving and belonging to the nation, measured by the readiness to sacrifice and die, constructed an image of the heroic man as the ideal citizen. This perpetuation of masculinized belonging and identity also has a spatial dimension, as one must wonder while walking along the streets in Syria that the dominance of the military-styled color khaki in the portraits of Hafez Al-Asad is a symbol of man’s strength and heroism.

Given the above, since Syria is a mosaic of ethnicities, religions, sects and nationalities, the relationship between these divided identities has not always been easy. The only glue that has kept them united is state-sponsored nationalism. This masculinist construction of nationalism used to formulate a binding identity orchestrated by the state and imposed from above.

The argument, which is systematically developed on this basis, is that nationalism is conceived as a perpetuated form of political behavior, propagated, maintained and reinforced in the context of establishing and modernizing the state. To conceptualize nationalism as a form of politics is to “relate nationalism to the objectives of obtaining and using state power”.[iii] Power, in this context, is principally about “control of state”[iv]. In essence, the very basis of this nationalism and its exclusion of half of Syria (i.e., women) proposes reasons for why Syrian nationalism is gender-specific and why women have been denied equality in the formation of national identity.

Rethinking the Nation

Given the current complex situation in Syria, as it is a nation in the remaking, the process of reconstructing and regenerating national identity prompts us to question how national identity has been defined and constituted in the second half of the 20th century to the present. In other words, the deconstruction of what I might call the ‘official’ story or narrative propagated by the Baath regime.

Women’s subordination in the political narrative has been through associating the right to citizenship with the readiness to die for the nation. This emphasis on sacrificial heroism has relegated women’s status as only men are conceived as defending the nation and preserving its honor by controlling women’s sexuality and choices. Thus, the construction of masculinism and the idealization of men’s superiority as preservers of ‘ird (honor) and ’ard (land/nation) in the political narrative is synonymous with the feminization of the woman’s body as a marker of the nation’s boundaries.

In a period when it has become impossible for any Syrian not to develop strong political positions and alignments, both personal and political enquiries persist, there will be questions related to what the future holds for the Syrian people, and how women will be portrayed in any newly employed nationalist ideology, though currently they are not included in the peace negotiations.

Nonetheless, at present, the process of nation-building while fighting despotic regimes and terrorist groups continues, with interethnic and sectarian relations fundamentally altered by the changes in power relations. Indeed, in such circumstances, development of nationalism in Syria will be confronted by the failure to create any stable government in the future.

However, in the event of the fall of the Baathist regime, the writing and rewriting of history will be intimately linked to currents and fashions in national politics. An imposed state or political system that does not support and encourage a gender-inclusive policy would slavishly follow the same exclusivist pattern of Syrian nationalism.

Given the geopolitical context of the Syrian case, the Syrian people face many scenarios that carry a particular set of nationalistic sentiments. Even if the Syrian regime will cease to have power over mobilizing a national narrative of any sort in the near future, we are still faced with fierce speculation and personal questions as to what is the nation and how we define our national love and belonging. Closely related to this enquiry is how much this nationalism will still have an implicit impact on defining our identity and belonging. How much have Syrians internalized the Baathist ethos and ideals? Will the Syrian war impose new definitions of national ideologies based on different geographical entities?

The attempt to answer these questions will appeal to a wider audience beyond the important core of scholars and students in the social sciences, particularly those with an interest in nationalism, who will be its key constituency.

[Main photo: Damascus schoolgirls during a standard drill. The image, published by National Geographic in 1974, stated: “The teen-agers must learn to drill, discipline, nursing and some weapons handling.” (National Geographic/Fair use. All rights reserved to the authors)].

[i] Tala’i‘ Al-Ba‘ath is an educational organization that includes Syrian children from the first to the sixth grade of primary education. The organization indoctrinates children and perpetuate Baathist ideals through extracurricular activities in the various vanguard centers, such as summer camps and clubs. The Vanguards (Tala’i‘) were founded in 1974 under the guidance of the late president, Hafez Al-Asad. The Revolutionary Youth Union (Ash-Shabibah) was founded in 1970. It includes Syrian youth from 13 to 35 years old and aims to reinforce the ethos of national struggle, revolution and defense.

[ii] This slogan was drummed into us in all the mass marches.

[iii] Bruilly, John. 1993. Nationalism and the State. 2nd edn. UK: Manchester University Press, p.1.

[iv] Ibidem.